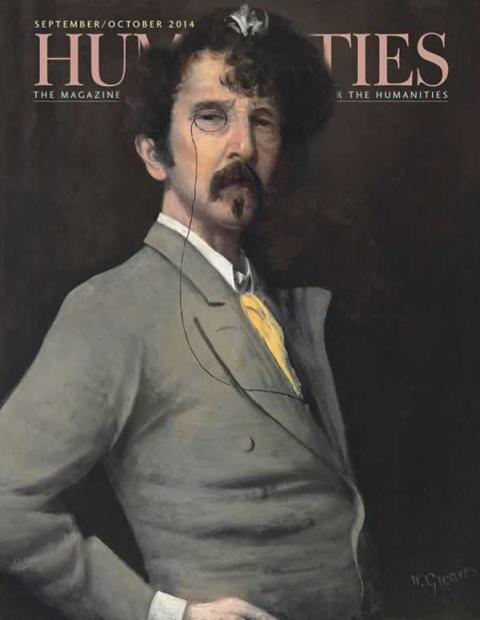

On Monday, November 25, 1878, James McNeill Whistler donned his usual costume. It is easy to picture him shrugging into his black woolen frock coat, admiring the snug fit through the shoulders and waist before the material flared and fell, slightly A-line, around his narrow hips. In the mirror, he examines his loose, dark curls, which add several inches of height to his fine, but rather slight, figure, making very certain his one white forelock isn’t obscured. He checks for his monocle and reaches for the thin walking stick he carries with him, ready to gesture at some witty or barbed point he might make. His signature look assembled, Whistler heads off to the Exchequer Chamber in London’s High Court of Justice to testify in his libel suit against the eminent critic John Ruskin.

No mere court case, it was, as art historian Linda Merrill writes in her book, A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin, “the most celebrated lawsuit in the history of art.” In challenging Ruskin’s scathing critique of his painting Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket, Whistler not only had at stake the extraordinary sum of one thousand pounds, but his reputation as an artist as well. During the trial, his artistic principles and especially his belief that art should be appreciated and admired for its beauty alone would be challenged, and his defense of his work would be quoted in newspapers in England and abroad.

“The artist’s ability to choose . . . was on trial,” explains David Park Curry, a senior curator at the Baltimore Museum of Art, in James McNeill Whistler and the Case for Beauty, a new film by Karen Thomas.

The trial and its outcome would become a defining moment in Whistler’s career, and one of the first and very public examples of an artist asserting control of his work, his artistic philosophy, his reputation, in short, his brand.

At the time of the trial, Whistler had lived in England for nineteen years, having left Paris for London in 1859 at the age of twenty-five. In Paris, the expat American and West Point dropout was known for his exquisite etchings, often compared to Rembrandt’s, and later, for his nascent oil paintings rendered in the realistic style of Courbet and influenced by the philosophy of Baudelaire, who urged artists to paint the life around them.

London, however, offered new opportunities away from the more competitive art scene in Paris. The recent exhibition “An American in London—Whistler and the Thames” at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C., showed that the change of scenery agreed with Whistler artistically, as he began the most productive and creative part of his career.

“He goes to Britain because he thinks he can do better there,” Curry explains in the film. “Britain wasn’t nearly as advanced as France in its sophistication about how to paint, in its audiences.” In England, Whistler had the advantage of being a big fish in a smaller pond. London also boasted a bourgeoning middle class eager to prove its cultural mettle through purchasing art.

It was a canny economic move as well as an aesthetic one. “It was really important for Whistler to distinguish himself, and to assert his originality and his uniqueness,” explains Lee Glazer, a curator at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Whistler was a gadfly and a promoter of his own work certainly, says Glazer, but not only because of his often outsized personality, but because he was well aware of the changing economic nature of the nineteenth-century art world, where the artist must play an active role not only in the production but in the management of his art. He was “astute at understanding that he was living in a new world for artists, and one in which artists no longer had the same kind of patronage structures of the past, and that art was a commodity like anything else, just a more luxurious one,” says Glazer. “He also understands that money is what makes creativity possible.” Whistler, who grew up in relative middle class comfort in St. Petersburg, Russia (his father was an adviser to the Moscow–St. Petersburg railroad), would not be a starving artist if he could help it.

During his first years in London, Whistler continued to paint in a realistic style. His self-deemed “masterpiece,” Wapping (1860–64), a river scene featuring three figures overlooking the Thames, was accepted into the Royal Academy, and he was rewarded with a small but steady patronage. But, in 1862, after Symphony in White No. 1: The White Girl, his portrait of his mistress, Joanna Hiffernan, was rejected by the Academy, Whistler, tiring of the constraints of realism and suffering a crisis of confidence, began a self-imposed period of intense study and experimental painting.

Glazer explains: “Whistler talks about this in some letters: that he was seduced by that damn realism and it was so easy to just paint what was out there. And I think maybe he worried that he wasn’t being original enough, that he was too closely associated with Courbet, that he hadn’t been well-trained. And that he had kind of gravitated to Courbet’s realism because of his lack of training.”

What emerged from his study was a new style of painting that eschewed the Victorian emphasis on realistic renderings of nature and history that told a narrative, illustrated a moral, or taught a lesson. “The majority of English folk cannot and will not consider a picture as a picture apart from any story it may be supposed to tell,” he complained. Instead, heavily influenced by the style of Japanese woodblock prints, Whistler created a new sort of picture, one that he hoped would be valued for its beauty and arrangement of color alone: art for art’s sake. The new paintings were signed with a butterfly, Whistler’s nickname, and became his identifying mark, appearing on the canvas itself and on the frames that he designed.

Prominent in this new phase of work was the series known as the Nocturnes. Set in and around the Thames, including views of Battersea Bridge and nearby Cremorne Gardens, these oil paintings were moody, atmospheric, and dark, and often punctuated by a bright tumble of tiny dots meant to resemble fireworks exploding over the river. Human figures were blurred suggestions, shadows abounded, fog was a given. They were brooding, twilight-lit, and very beautiful. It was this series of paintings, on exhibit at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, that became the flashpoint for Ruskin’s harsh review.

In the late nineteenth century, no writer was more renowned or respected than John Ruskin. A huge cultural figure, he was known not just in Britain, but in the United States and on the Continent. In art, he defended “truth to nature” and valued historical narrative, championing first the painter J.M.W. Turner and later the work of pre-Raphaelite artists such as Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who celebrated mythology and Arthurian legend.

It’s possible that the context of the Grosvenor Gallery, which opened in spring of 1877 as a new art space funded by Sir Coutts Lindsay of Balcarres, played a role in Ruskin’s discomfort as well. Instead of asking artists to submit works, the Grosvenor operated by invitation only. Rather than showcasing a single artist, the works of several artists were grouped together. Finally, Sir Coutts made a point of inviting artists who might not be well known to exhibit. Ruskin objected on all counts. That Whistler’s works were displayed along with Burne-Jones’s The Beguiling of Merlin, with its strong-featured figure draped in flowing cloth (and which contemporary readers will recognize from its reproduction on the cover of A. S. Byatt’s 1990 best-selling novel, Possession), only fueled Ruskin’s fire.

Although eight Nocturnes were on display, Ruskin aimed his verbal arrow at Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket, a view of fireworks falling over Cremorne Gardens. In his pamphlet, Fors Clavigera, Ruskin praised the work of Burne-Jones before taking on “the modern school” in the form of Whistler. First, Ruskin took Sir Coutts to task for “admit[ing] works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of willful imposture.” Then he lashed out at the artist himself: “I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now, but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” The critique stung, yet it also presented an opportunity. What if Whistler could capitalize on this vicious attack?

“Whistler was a nice American pragmatic realist,” says Curry in an interview. “He was eminently practical.” And so, affronted, deeply in debt, and seizing an opportunity both to proclaim his philosophy of art to the world and win money to pay off his creditors, Whistler decided to sue for libel.

It was not the first time that Whistler, a notorious self-promoter with a remarkable talent for turning a phrase, had taken a stand against critics in a public forum. When P. G. Hamerton, writing in the Saturday Review, remarked that Whistler’s Symphony in White No. III, a portrait of two women dressed in white arranged near a white sofa, contained “many dainty varieties of tint, but it is not precisely a symphony in white,” Whistler responded in kind by taking the critic to task for his literal reading:

Bon dieu! did this wise person expect white

hair and chalked faces? And does he then, in

his astounding consequence, believe that a

symphony in F contains no other note, but shall

be a continued repetition of F, F, F.? . . . . Fool!

Similarly, when a critic writing for The World characterized an etching in Vanity Fair of St. James’s Street by Whistler as “sadly disappointing,” Whistler took pains to point out that “the impression in Vanity Fair that disappoints him is not an etching at all, but a reproduction for that paper by some transfer process.”

The trial took only two days. Ruskin was too ill to attend, but several artists, including Burne-Jones, took the stand to defend Ruskin’s position, though the defense of Ruskin was more of an attack on Whistler. Under questioning from Charles Synge Christopher Bowen, counsel for the defendant, Burne-Jones characterized Whistler’s work as “incomplete . . . an admirable beginning,” “deficient in form,” and without composition. He damned with faint praise Whistler’s skills as a colorist, saying, “I have already spoken of the merit and color of Mr. Whistler’s pictures, and of their almost unrivaled appreciation of atmosphere; but that is all that can be said of them.”

In his questioning of Whistler, the other counsel for the defendant, Sir John Holker, took careful pains to characterize Whistler’s differences as oddities. Whistler was pressed to define his use of terms, including “nocturne” and “arrangement” (recall that one of Whistler’s most famous portraits, that of his mother, was titled Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1). His paintings were used as evidence for the defense, with Holker demanding explanations about their composition and the artist’s aim, suggesting of Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge that it was impossible to tell right side up from upside down.

In one of the most reported exchanges, Holker asked Whistler: “How long do you take to knock off one of your pictures?” Whistler replied: “Oh, I ‘knock one off’ possibly in a couple of days—one day to do the work and another to finish it,” prompting Holker to ask: “The labor of two days is that for which you ask two hundred guineas?”

“No,” said Whistler, “I ask it for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime.”

According to Lee Glazer, this answer, clever and pithy as it is, references the level of self-consciousness that Whistler had about his process. “His art has become so radically reduced by the time you get to the Nocturnes. It’s really intense—like a sauce—and truly the knowledge accrued over the course of a lifetime of going from one mode of depicting the world to another.” In the process, Whistler had learned “a whole new language.”

Whether or not the jury completely understood Whistler’s argument, they found in Whistler’s favor, but at a cost. He was awarded only a farthing instead of the one thousand pounds he had asked for. The Pyrrhic victory affected him deeply. The court costs, on top of his own considerable debt, sent him into bankruptcy. “When he sued Ruskin for libel, it was a publicity stunt in a sense,” explains Glazer. “It was a way to kind of draw attention to himself and try to explain what he was doing. And he thought by doing that, in a public setting like a trial, that the art world would rally around him and support him. And what I think was so devastating to him on a really deep level was that most artists did not do that.” In 1879, Whistler lost his home and its contents, and subsequently moved to Venice to restart his career by returning to his first art, etchings. Although he lived for another twenty-three years, he never returned to painting nocturnes.

Today, it’s hard to imagine the confusion and misunderstanding the Nocturnes caused, but for the Victorians, these deeply impressionistic renderings seemed radical. “People didn’t have the vocabulary for it,” says Linda Merrill in the film. “They couldn’t describe Whistler’s paintings as nearly abstract because that word just wasn’t part of the lexicon yet. So it was difficult for them to know what it was exactly about Whistler’s paintings that seemed so avant-garde.” Today, art historians consider the trial as a defining moment, a turning point in the emergence of a new and modern art, and a new and modern artist who becomes as known for his personality as for his art.