Near the dawn of the twentieth century, a young Englishwoman named Lucy is visiting an ancient church in Florence, unsure of what she is looking at, or how, exactly, to see it. She doesn’t have her Baedeker, a popular travel guide, and is feeling lost without it. “She walked about disdainfully,” we learn, “unwilling to be enthusiastic over monuments of uncertain authorship or date. There was no one even to tell her which, of all the sepulchral slabs that paved the nave and transepts, was the one that was really beautiful, the one that had been most praised by Mr. Ruskin.”

The woman unsure of her own reaction to a lovely church without consulting “Mr. Ruskin” is Lucy Honeychurch, the heroine of E. M. Forster’s celebrated 1908 novel, A Room with a View. The reference to “Mr. Ruskin” might be lost on many modern readers, although Forster obviously felt no obligation to explain it when he wrote his story. The man in question, John Ruskin, had died eight years earlier, in 1900, but his memory was still fresh in popular culture. In Ruskin’s heyday, just about every educated Victorian knew who he was.

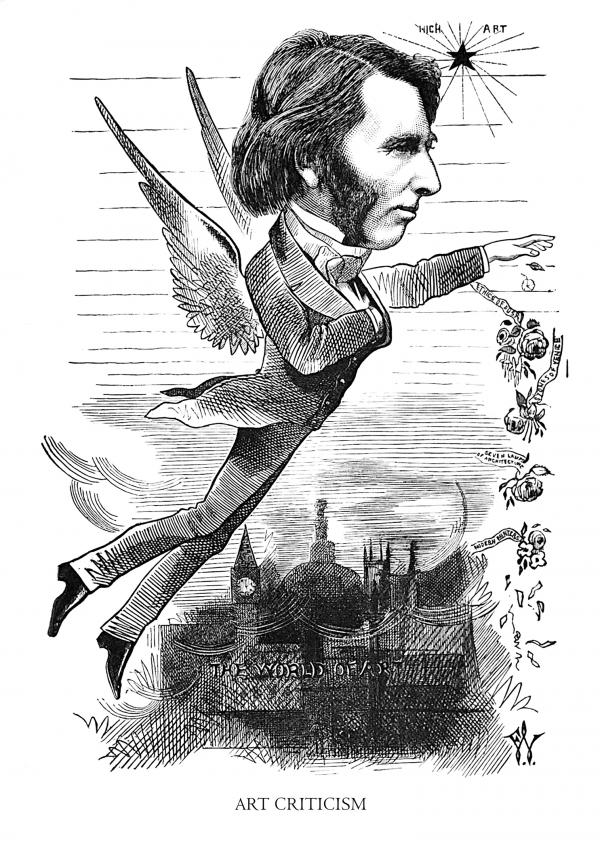

Born in 1819 to a wealthy merchant and an overbearing mother, Ruskin was an English writer on art, nature, literature, and political economy who dominated cultural thought throughout Britain—and, to some degree, the Western world—in the second half of the nineteenth century. Given his relative obscurity today, it’s hard for contemporary readers to grasp how famous Ruskin once was. Reverently read and reflexively quoted, his pronouncements on everything from painting to poetry to private capital rang among his fans with an almost scriptural authority. His mother had once longed for him to be a bishop, and as an arbiter of his society’s standards, Ruskin, in his own way, came close. “Taste . . . is the only morality. . . . Tell me what you like,” Ruskin asserted, “And I’ll tell you what you are.”

Forster was being wry when he mentioned Lucy’s predicament—that she didn’t know what to think until Ruskin had told her what to think. But Forster’s tongue-in-cheek remark also acknowledged the spell Ruskin once cast over people of culture—or, at the very least, people who wanted to be considered culturally sophisticated. The slavish devotion of Ruskin’s disciples irritated D. H. Lawrence, who found it all a bit much. “The deep damnation of self-righteousness . . . lies thick over the Ruskinite,” Lawrence lamented, “like painted feathers on a skinny peacock.”

Maybe Lawrence’s dart came poisoned with a little envy. What author, after all, wouldn’t want the kind of reception Ruskin enjoyed in his prime? Ruskin’s many books, “bound in vellum or limp leather, were to be found lying beside the Idylls of the King on the tables of those who did not normally read, but wished to show some evidence of refinement,” the late art historian Kenneth Clark observed. “For almost fifty years, to read Ruskin was accepted as proof of the possession of a soul.”

Ruskin was revered not only by the public, but by other writers and noted thinkers, including British prime minister William Gladstone. “From Wordsworth to Proust there was hardly a distinguished man of letters who did not admire him,” Clark wrote. “Austere critics like Leslie Stephen believed him to be one of the unassailable masters of English prose, and, on the death of Tennyson, Gladstone (whom he habitually insulted) wished to make him Poet Laureate.” Gandhi and Tolstoy would claim him as a powerful influence, too. Charlotte Brontë claimed that she did not truly perceive visual art until she read Ruskin’s Modern Painters. Ruskin, she said, “seems to give me eyes.”

Ruskin did not become England’s poet laureate, which was no doubt for the best, since he wrote very little poetry, and most of it was forgettable. Even so, readers tended to think of Ruskin as a kind of poet, since his prose style, rich in metaphor, leaned toward the rhapsodically romantic. Victorians versed in Wordsworth loved this sort of thing, but to the modern ear, Ruskin can often seem overdone. Here’s how Ruskin describes a swallow: “It is an owl that has been trained by the Graces. It is a bat that loves the morning light. It is the aerial reflection of a dolphin. It is the tender domestication of a trout.” There you have it, a swallow compared to a bat, a dolphin, and—in a phrase only dear Ruskin could coin—“the tender domestication of a trout.” It’s as if Ruskin is free-associating metaphors before our eyes, hoping that something, anything, will stick.

Ruskin could get carried away on the page as he so often got carried away in life, and his sense of abandon somehow resonated with Victorians who found, in their socially constrained era, a sense of liberation in reading his sentences. He was, in a number of respects, the quintessential Victorian, his desire for strict moral probity conflicting with serious personal demons. Ruskin dominated his age because he frequently seemed so thoroughly a part of it, but there remains a question about whether his work deserves to endure as more than a period piece.

What is true, and has been for years, is that few people read Ruskin anymore. ”No other writer, perhaps, has suffered so great a fall in reputation as Ruskin,” Clark noted in 1962. A generation or two later, Ruskin’s profile remains low. An edition of his Collected Works stretched to 39 volumes, but little of it remains widely available in print. The sheer size of his oeuvre is an abiding complication, mixing the good with the bad, all of it defying the kind of easy summary that makes a literary persona truly marketable.

Like the house where he once lived, which was full to the brim with art, books, and curios: “Ruskin’s life and work are crammed with things, so that it is not perhaps too surprising that he has survived piecemeal,” his biographer, John Dixon Hunt, has mentioned. For the newcomer, the best introduction to Ruskin is his Selected Writings, a Penguin Classic arranged and introduced by Clark, which is, sadly, no longer in print. From Ruskin’s enormous output, Clark distilled about 350 pages of prose on art and architecture, nature, society, and economics. His extracts are necessarily fragmentary, but, intentionally or otherwise, Clark’s editorial scheme deftly expresses Ruskin’s kinetic mind, which favored movement and change over a sustained and systematic argument.

Here’s a Ruskin passage that says a lot about how he wrote:

I believe we can nowhere find a better type of a perfectly free creature than the common house fly. Nor free only, but brave; and irreverent to a degree which I think no human republican could by any philosophy exalt himself to. There is no courtesy in him; he does not care whether it is king or clown whom he teases; and in every step of his swift mechanical march, and in every pause of his resolute observation, there is one and the same expression of perfect egotism, perfect independence and self-confidence, and conviction of the world’s having been made for flies.

First and foremost, perhaps, Ruskin’s rumination suggests his powerful attention to detail. That he would focus so perceptively on a little bug that everyone regards as a nettlesome house pest really speaks to the kind of eye his admirers came to love. His gift for seeing the tiny thing that implies the larger truth made him a compelling art critic, able to interpret geniuses of antiquity and his own time in such expansive works as Modern Painters, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and The Stones of Venice. Secondly, of course, his reflection points to an abidingly political sensibility. In Ruskin’s rendering, the house fly becomes a way to consider the nature of human freedom—the degree to which we should embrace convention and tradition, and the extent to which we should flout it.

The idea no doubt struck Ruskin’s straitlaced Victorian contemporaries as a radical one, dampening his appeal among the ruling establishment. Another quality of this passage is its resistance to quick classification, touching on aesthetics, politics, and the natural world. Clark tucks it into a subject heading on society and economics, but it would just as easily have been right at home in the anthology’s sections on art or nature. Ruskin insisted on seeing one thing as connected to everything else, which is why his discussions of art led him into questions of politics. He thought that good art grew best from good social conditions. Ruskin was skeptical about technological progress, an early prophet of the perils of pollution, and worried about the market principles underlying capitalism.

“The first of all English games is making money,” he complained. “That is an all-absorbing game; and we knock each other down oftener in playing at that, than at foot-ball, or any other roughest sport: and it is absolutely without purpose; no one who engages heartily in the game ever knows why.” He warned his fellow Englishmen that coal mining and consumption were threatening to destroy the air and land that had made their country great. All “the true greatness she ever had,” he said of England, “she won while her fields were green, and her faces ruddy; and that greatness is still possible for Englishmen, even though the ground be not hollow under their feet, nor the sky black over their heads.”

Although Ruskin was generally wary of the changes transforming nineteenth-century commerce, those same changes helped create a class of tourists who became a core audience for his books. “There is nothing that I tell you with more eager desire that you should believe . . . than this,” he once told a lecture audience, “that you will never love art well, till you love what she mirrors better.” What Ruskin seems to be saying is that a painting or piece of sculpture should be tested against the landscape and culture it’s intended to represent. That idea resonated with nineteenth-century readers, who were increasingly able not only to see the art of places like Venice in museums, but to visit these destinations. Ruskin became a celebrity interpreter of what English families might see abroad, his books a welcome traveling companion.

With growing prosperity, tourism was becoming a mass market, and Ruskin a crucial figure in mediating this newly opened world. “The Grand Tour had been an institution among aristocrats, in which men and women of privilege traveled through Europe as if it were a finishing school, absorbing its art, culture and languages at their leisure, the better to enrich themselves and English society on their return,” scholar Radhika Jones has noted in explaining the mood of the time. “Why should the professional classes, and maybe even working-class men and women, not engage in that pursuit as well?”

Although he enjoyed success as an author and lecturer, Ruskin’s personal life was a mess. His mother was an early helicopter parent, accompanying him to Oxford and renting rooms for herself there when he attended the university. His 1848 marriage to Effie Gray ended several years later, and she had it annulled on the grounds that their union had never been consummated. In 1859, he fell in love with a 10-year-old girl, Rose La Touche, waiting until she was 18 to propose marriage. The marriage never happened. La Touche died in 1875, and the loss advanced Ruskin’s lapse into dementia. He died a broken man in 1900, just as the century he had done so much to shape was receding from view.

Ruskin’s sexuality has sparked intense speculation. Its creepier aspects have, understandably, complicated his popular reputation. “Ruskin, who seems to have been incapable of normal relations with a grown-up woman, had a passion for little girls,” Clark flatly declares. “As a man of forty he used to stay in a girls’ school called Winnington, where he joined in the games and talked to the girls about history, geology, and morals, conversations which he polished up into a book called The Ethics of the Dust.”

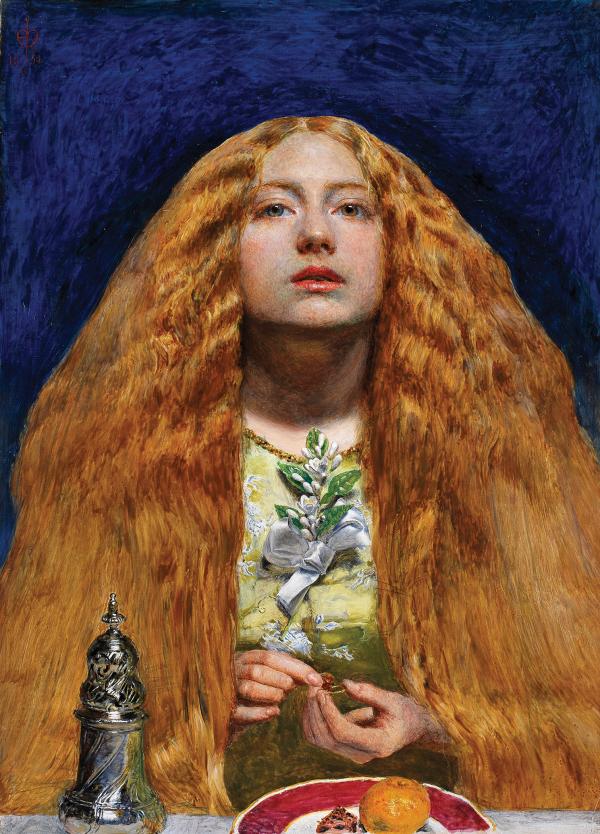

Ruskin’s doomed marriage was dramatized in a 2014 movie, Effie Gray, that frames Ruskin’s controlling mother, played by Julie Walters, as the center of his marital troubles. Greg Wise, a handsome actor tricked out in high collars and muttonchop whiskers, got points from critics for approximating Ruskin’s striking countenance. A different take on Ruskin emerges in Mr. Turner, a 2014 movie starring Timothy Spall as the enigmatic landscape artist J.M.W. Turner. Ruskin tirelessly championed Turner’s paintings, helping to turn the tide of public opinion in the painter’s favor. In embracing Turner, whose eerily experimental paintings anticipated Impressionism by nearly a half century, Ruskin showed that he could be a tribune of the avant-garde. But he wasn’t uniformly welcoming of new methods, dismissing a work by American painter James Whistler as “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” (That critique, which prompted a controversial lawsuit, was the subject of a 2014 Humanities story.)

In Mr. Turner, actor Joshua McGuire plays Ruskin for laughs; Ruskin speaks with a pronounced lisp, his character described by film critic Robbie Collin as “an oblivious smartypants.” The recent film treatments of Ruskin prompted English nature writer Philip Hoare to publish a lengthy defense of Ruskin in the Guardian, complaining that neither of these dramatizations gets at the complexity and intellect of their subject. Ruskin “was a great artist in his own right,” Hoare tells readers. “His watercolors of Swiss mountains and nature studies speak of an extraordinary brilliance, made more passionate by their creator’s intent.”

Ruskin also championed the new medium of photography, according to Hoare, and his newsletters, which arranged news clippings in a lively stew, anticipated the modern blog. In nonfiction narratives such as The Whale and The Sea Inside, Hoare has extended Ruskin’s practice of exacting observation. The most obvious bridge between Ruskin and contemporary writers such as Hoare is Praeterita, the memoir that Ruskin worked on during his final years. Instead of straight chronology, it unfolds in a kind of pointillist collage, creating a style that informed the work of Marcel Proust.

Ruskin developed Praeterita—the title, he said, “means merely past things”—at the hinge between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Its sensibility suggests a writer leaving behind the solemn grandiosity of an earlier age to embrace a style that’s simpler, more direct, more intimate. In his earlier books, Ruskin’s voice could often seem oracular, disembodied, drenched in transcendental moonshine, as in this passage: “Our whole happiness and power of energetic action depend on our being able to breathe and live in the cloud; content to see it opening here and closing there; rejoicing to catch, through the thinnest films of it, glimpses of stable and substantial things.”

But when the narrative truly hums in Praeterita, we see a real man, not an airy mystic, a homely mortal grappling with the grit and gristle of earthly experience. Parts of Praeterita are quite affecting, as when Ruskin recalls, without morose self-pity, the severe household of his early years, when he was allowed only a handful of toys. By default, he looked to the world as his plaything, “tracing the squares and comparing the colours of my carpet . . . examining the knots in the wood of the floor, or counting the bricks in the opposite houses.” In these modest exercises of the imagination, the discerning eye of a critic was born.

As Ruskin’s mind declined, the text of Praeterita declined with it. It’s a flawed book—yet, because of its imperfections, a truly human one, a striking epitaph for a man who came to see his work as not a detached commentary on life, but rooted in life itself. “All great art,” he wrote, “is the work of the whole living creature, body and soul, and chiefly of the soul.”