On a spring morning, a small crowd of curious, if slightly perplexed, middle school students stand looking at an artist's self-portrait. In the painting, the artist tells his story, warts and all. With its shimmering golden-yellows and vermilion, the painting presents a regal-looking man sitting in an armchair holding a cane topped with a shiny silver knob.

A closer inspection of his face reveals sagging chins, a bulbous nose, and imperfect skin—a face eroded by illness, misfortune, or perhaps discontent. This is a self-portrait. One student wonders why the artist didn't improve his own looks. Another asks why he's dressed in a costume that obviously is not his regular clothing. “What is he trying to hide?” this student wonders.

Back in the classroom, under the guidance of their teacher, Joanell Meringolo, the students search out the artist's biography and uncover the fact that the portrait was painted when the artist was at a financial low, unable to pay back the loan on his stately home in Amsterdam. The date coincides with a period when the artist begins to embrace a sparer, less extravagant lifestyle, which seems at odds with the artist's lavish attire. Perhaps, the students hypothesized, he donned this luxurious attire to safeguard his pride.

The artist in question is Rembrandt, and the work is his 1658 Self-Portrait. Ms. Meringolo concludes that this field trip to New York's Frick Collection to show her students a masterpiece has paid off. Her students do not think of Rembrandt as some art legend but as a man who bounced back to meet life's challenges. He is more resilient—and real—than they would have guessed.

Humanizing the artist is a goal of the NEH-supported project “Rembrandt and Collections of His Art in America.” In the project, Meringolo and a team of fellow New York City public school teachers; professors from Long Island University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and museum educators from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Frick Collection, The Asia Society and Museum, and the Nassau County Museum of Art are creating a Web site about Rembrandt that will meet the recommended national teaching standards in the visual arts and social studies. Using thematic strands recommended by the National Council of Social Studies, the project ties in works of Rembrandt with larger themes of culture, civilization, and identity to help students see the timelessness and universality of these concepts. The Web site, which goes live in fall 2008, will use paintings, etchings, and drawings by Rembrandt from American museums as case studies in lesson plans.

“Looking” episodes, such as the one by the students visiting The Frick Collection, prompt a larger question: Why teach Rembrandt at all?

How will today's e-mailing, e-gaming, e-everything youths find meaning in the life of a painter born four hundred years ago in a world so strange and distant from their own? As remarkable as it may seem, Rembrandt proves to be a comfortable twenty-first century fit for students—especially in the realms of storytelling and understanding symbols.

Take, as an example, The Polish Rider, circa 1655. This enigmatic work, whose meaning and provenance has long puzzled scholars, is brimming with ideas for enterprising teachers to seize.

When the teachers tell students that the subject of the work is still unknown, it can prompt all kinds of speculation, just as it has among art historians. Who is this character on horseback? Is it a Biblical or historical or literary figure? Is the rider Polish or, perhaps, Dutch?

Adding to the mystery is the setting. Where is the episode taking place? Why the solemn, shadowy landscape and its imposing rocks? And the faint flicker of fire in the background. What could that mean?

Classroom discussions offer an opportunity to ask the big question about this painting: Is it really a Rembrandt? Students learn about art authentication and the work of the Rembrandt Research Project in Amsterdam.

Established in 1968, the group investigates and verifies paintings that have been attributed to Rembrandt. In 1997, Dutch art historians gave their seal of approval to The Polish Rider, but even these experts are still uncertain whether the painting is a product of only Rembrandt's brush. In an attempt to make the work more salable, it may have been finished in haste by another artist, perhaps a pupil of Rembrandt's, adding yet another intriguing layer to the story. What better lesson in critical thinking is there than to have students enter the complex world of this painting?

Another benefit of teaching Rembrandt is its potential to build visual literacy. While children are exposed to more and more electronic media, the still composition of masterly paintings offers many a lesson in discernment and the importance of the telling details.

An example of this can be found in a lesson given by a teacher who used the Rembrandt painting Woman with a Pink, early 1660s, with her class. After viewing and discussing the work and calling their attention to the symbolism of the pink carnation held by the woman as a sign of marital fidelity, the teacher asked the students to come up with their own meaning. In response, one student wrote:

I am lonely but hold

a flower of hope;

And I fill it with love.

I give it more life

Because it is faithful to me

The groundwork for “Rembrandt and Collections of His Art in America” was laid several years ago. In a prototype project in the New York City public schools, a group of teachers began using Rembrandt's art as the jumping-off point from which to improve literacy and teach social studies, art, and other subjects.

One teacher instructed her students to look at Rembrandt's Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, 1653, and record their initial impressions of it in a journal over several days. Students constructed personal narratives in which they engaged the work's characters and brought the scene to life.

Rembrandt's Daniel and Cyrus before the Idol Bel offers social studies teachers a springboard into the Protestant Reformation, Counter-Reformation, the Thirty Years' War, and other events in seventeenth-century Europe. In the painting, the lavishly dressed Cyrus is larger in relation to the submissive Daniel. How might this work reveal events and attitudes in seventeenth-century Europe? Are Daniel and Cyrus just Biblical figures, or do they also stand in for the asymmetry of power between seventeenth-century Holland and the powerful King of Spain?

What motivated Rembrandt to choose Biblical themes? Quite possibly it was the market. Citizens of the seventeenth-century Calvinist Dutch Republic wanted such paintings because the Reformation had roused their interest in Old and New Testament history. But it is not only Biblical personages who emerge from the hand of Rembrandt. Many of the settings of his drawings and etchings pluck their characters from ordinary and sometimes difficult circumstances.

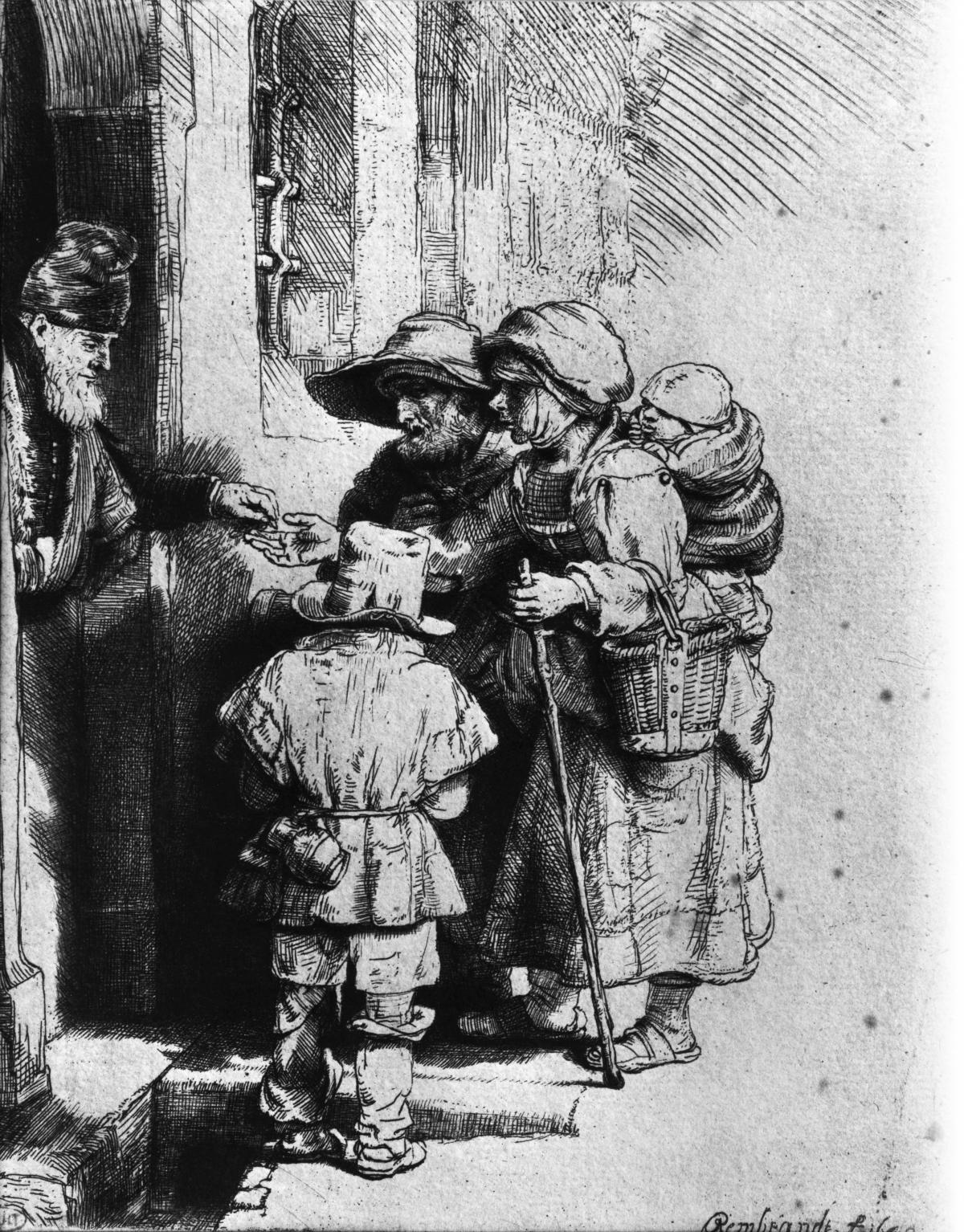

If art is the expression of beauty, then it would seem artists choose their subjects to represent an ideal beauty—as in a Degas dancer, a Raphael Madonna, or a Vermeer interior. Not so with Rembrandt. One need look no further for an example of this than Beggars Receiving Alms at the Door of a House, a 1648 etching.

It would have been easy for Rembrandt to depict the growing prosperity of the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth century. A number of Dutch painters of the time made a handsome living doing so. But he refused to limit his interest to those who could pay for his services. While many Dutch towns became the envy of Europe for their efficient removal of beggars and other indigents from central areas, Rembrandt extended his artistic sympathy to people who pled for scraps and the spare coins of the well-to-do. Those who lived on the fringes of society were not without dignity and were worthy of inclusion in art.

Taking a cue from this theme, one teacher from the public schools' initial New York Rembrandt Project combined exploration of the etching with the study of a book called The Whipping Boy. The 1987 Newbery Award-winning book by Sid Fleischman is set in medieval times and has as its protagonist an orphan named Jemmy who served as a whipping boy. He is subjected to beatings for the frequent misbehavior of the aptly named Prince Brat.

In the lesson following the class's reading of the book, the teacher displayed a reproduction of Beggars Receiving Alms. He had the class discuss the attitudes of both Rembrandt and the novel's author toward society's underclass. Among the questions that were probed were whether writers and artists have the power to change how a society views itself.

Being an “agent of civilization” is one of the many roles ascribed to teachers. If we are to have any expectations of producing a well-educated, well-prepared generation of deep-thinking, resourceful leaders, then it is essential to give students an opportunity to review, respond to, and ultimately revere the power of the human imagination—past and present. There may be no better way to promote this than to study, understand, and exult in masterpieces.

That's why we teach Rembrandt.