The set for Fu Pei-mei’s 1962 debut on Taiwan Television was little more than a makeshift wooden countertop in the middle of the television studio. The only special touch was a simple background featuring the outline of a cartoon fish made of black fabric, stapled to the wall, with the staples still plainly visible.

For the live broadcast, Fu had chosen one of her favorite dishes, sweet and sour “squirreled” fish (tangcu songshu yu), an attractive dish from Jiangsu province that requires careful deboning and scoring of the interior flesh of a whole fish, such that the entire fish puffs up like a squirrel’s tail when deep-fried. Squirreled fish was one of Fu’s favorite dishes to demonstrate in front of audiences because the end result was visually stunning and demonstrated the two pillars of Chinese cooking, knife skills (daogong) and heat-time (huohou). Precise knife skills and a properly sharpened cleaver were needed to scale, gut, debone, and score the fish, while keeping the tail intact and attached to both fillets. Precise timing and heat control were needed to deep-fry the fish in a wok without overcooking the delicate flesh.

Yet in order to accomplish all of this on the live television broadcast, Fu not only had to supply all the ingredients for making the dish—a whole fish, flour, egg for deep-frying, plus shrimp, tomato, mushrooms, peas, scallions, ginger, garlic, sugar, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, and starch for the sauce—she also had to bring along all her own cooking equipment, including a cutting board, wok, wok spatula, strainer, chopsticks, bowls, plates, and spoons. Fu’s three children and her mother, who had by then arrived in Taiwan from the mainland, were pressed into service to help carry everything to the television studio. With no connections for gas, electricity, or running water, Fu even had to lug along her own brazier, the heating element upon which she would actually cook. The brazier, commonly used at the time by housewives in Taiwan, was a heavy clay bucket with an opening on the side to tend to the lit charcoal while the wok sat on top—only a slight improvement on cooking over a campfire.

At the last moment, as she was carrying her equipment into the studio, Fu realized that she had forgotten to bring her cleaver. Along with a wok, this was the most essential piece of equipment for any Chinese cook. There was no way to demonstrate how to debone or score the fish without it. The assistant director told her to borrow one from the broadcast station’s cafeteria, so she ran off to find one. By the time Fu went on the air, the fire in her brazier, which she had lit in the corridor, had nearly burned out, and the borrowed knife was too dull to saw off the fish’s head. When Fu had just managed to get the fish frying in the wok, she saw the director making circular hand movements signaling her to hurry. Fu ignored her and went on preparing the rest of the dish, which included covering the fried fish with a thickened sauce of stir-fried vegetables and shrimp. As she finished, she didn’t have a chance to say goodbye to the audience before the director cut her off. Still, she had managed to bang out the dish on live television in more or less the allotted 20 minutes, all while sweating profusely.

When she got home, her husband, who had been watching her on the living room television, chided, “You were in such a rush! You really botched that one!” Fu, already upset that she had agreed to appear on television in the first place, was convinced that she had humiliated herself in front of the whole world. (This was a dramatic exaggeration—the broadcast did not reach the central or southern parts of Taiwan, and even in Taipei not that many families owned television sets yet.) So, Fu was doubly shocked when the following week she was invited to return to the cooking program by the producer, who told her that viewers had responded enthusiastically to her first appearance. Perhaps braised sea cucumber for the second episode?

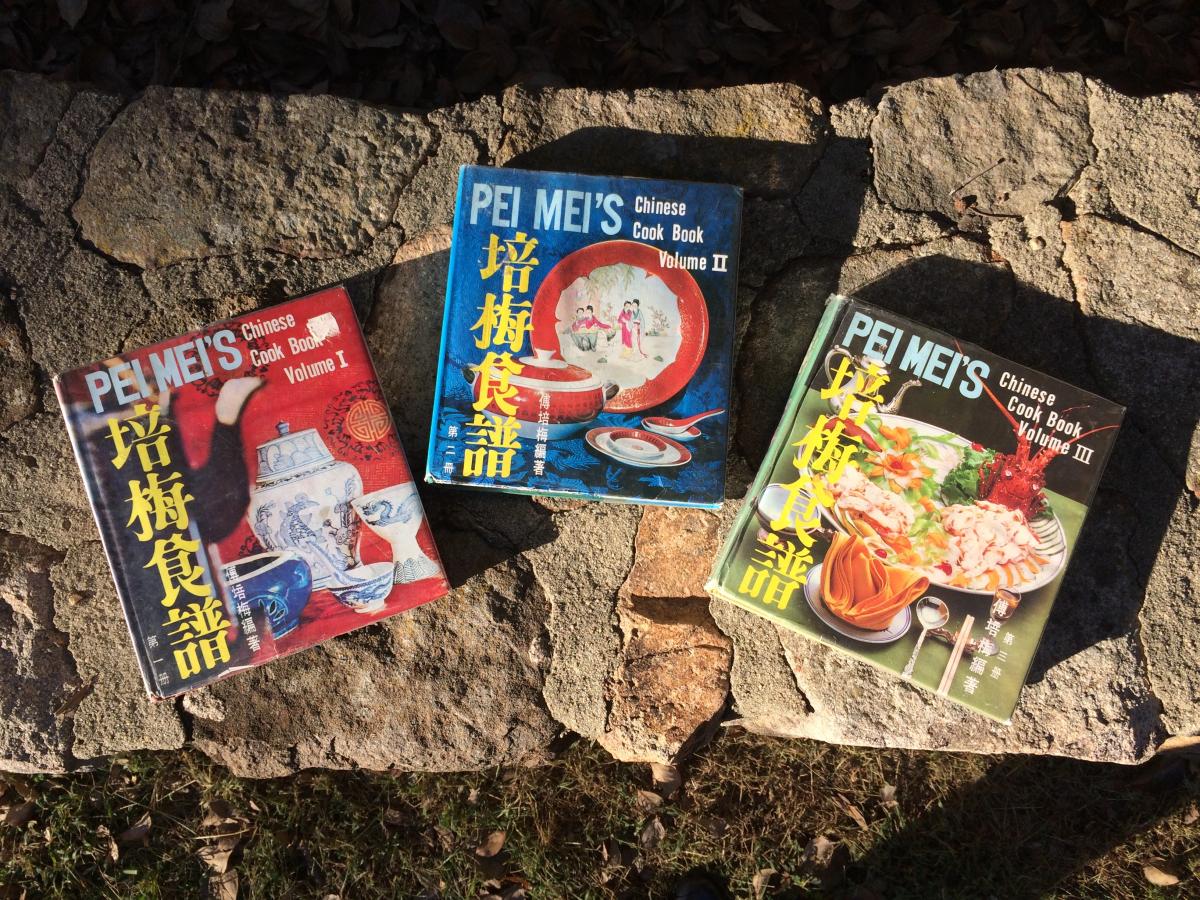

The introduction of television broadcasting to Taiwan in 1962 marked the beginning of a new media age. Television gave housewives in Taiwan a whole new way of learning what and how to cook. Little could Fu have imagined as she was rushing to finish her squirreled fish that this would be only the first of thousands of appearances on television, launching her eventual 40-year career as a television cooking instructor. Americans tend to think only of Julia Child when it comes to television cooking pioneers, but, in truth, The French Chef debuted a few months after Fu Pei-mei’s first television appearance. For millions of postwar viewers in Taiwan (and around the world), Child, with her warble of “Bon Appetit!” and her pot of boeuf bourguignon, was not a household name. Although Fu Pei-mei may have been introduced as the “Julia Child of Chinese cooking” to American audiences by the New York Times in 1971, for audiences in Taiwan, it made more sense to call Child the “Fu Pei-mei of French food.” There, it was Fu who served as the ultimate popular culinary touchstone, the televisual figure against whom all other cooking authorities were measured, no matter where they were from. British television host Delia Smith, for example, was profiled in a Taiwan newspaper as the “Fu Pei-mei of England,” while cookbook author Elinor Schildt was described as the “Fu Pei-mei of Finland.”

Fu’s success in television was by no means a foregone conclusion. Television cooking was modern cooking, and modern cooking in Taiwan explicitly meant two things: learning how to cook a variety of regional Chinese dishes and how to bake Western desserts. In the first three years of broadcasting, more than three dozen culinary experts demonstrated how to do both for the cooking segment of the women’s program on which Fu also appeared. Yet in the end it was Fu and Fu alone who would become Taiwan’s household name for television cooking. Fu’s tidy, youthful appearance, proficient standard Mandarin, and her deft ability to cook and talk simultaneously on camera made her an ideal choice for the new medium. Eventually, in the 1970s and the 1980s, both the picture-perfect image of domestic middle-class femininity and Taiwan Television’s emphasis on Mandarin language would be challenged as women overturned traditional gender roles and non-Mandarin-speaking linguistic groups asserted their cultural identities. Yet in terms of conveying complex culinary ideas over the small screen, Fu translated techniques and specialty dishes from different Chinese regions into a common idiom that could be shared with a broad public audience, demonstrating a modern, national sensibility in cooking across regional lines. With a dish of squirreled fish, a new television star was born.

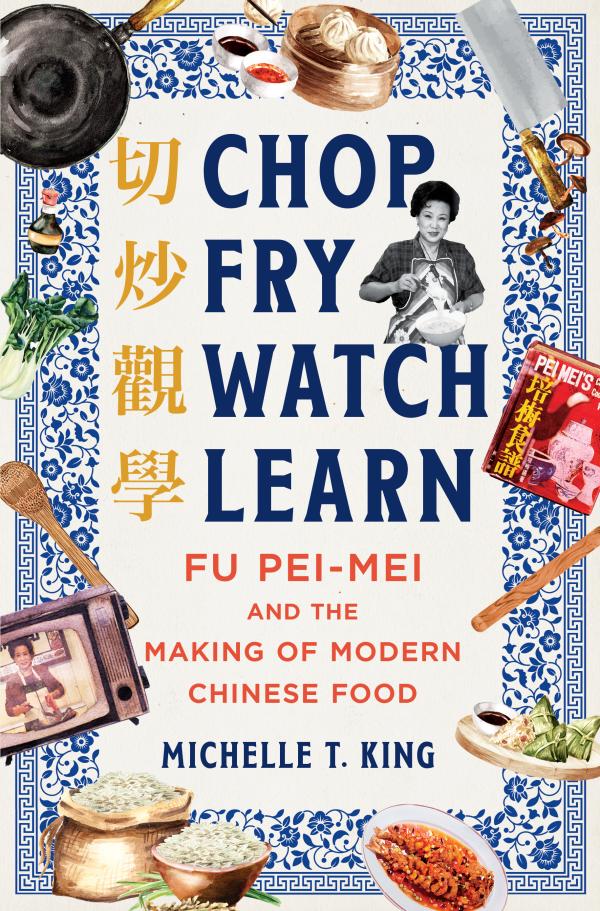

Excerpted from Chop Fry Watch Learn: Fu Pei-mei and the Making of Modern Chinese Food. Copyright © 2024 by Michelle T. King. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved.