“Eating is an agricultural act,” Wendell Berry once wrote. It’s also, of course, a historical and cultural act. For as long as humans have existed, we have looked to food for sustenance and emotional comfort. Before the current pandemic brought a shortage of therapists, grocery store shelves were picked clean of baking flour and yeast packets.

I happen to be an avid consumer of both food and history, so my pandemic coping habits have taken me further afield. Armed with a full tank of gas and a keen eye for roadside history markers, I’ve spent weekends following the winding roads that head west from Washington, D.C.

Beyond the capital beltway, highways turn into old turnpikes, leading to colonial towns and aging churches on whose walls the graffiti of convalescing Union and Confederate troops can still be read. There’s no better salve for modern worries than being immersed in the long view of history—and fresh air doesn’t hurt, either.

The real prize, however, is when the invisible lines of history intersect with the foodie trails of today. A snug tavern dining room that has offered peanut soup to travelers for the past 250 years. Or wild pawpaw groves that yield armfuls of the luscious indigenous fruit in late summer, as they did for the Piscataway tribe hundreds of years ago. General Washington slept here? Great, I say. Now tell me what he had for dinner.

Eating and cooking with the ingredients of past cultures is its own form of gustatory time travel: allowing us to dine with soldiers of the Continental Army for breakfast, to lunch with a Cherokee warrior, and to have dinner with an Appalachian miner. Their names may not be known, but the flavors, ingredients, and recipes that shaped their lives have been passed down. A square of cornbread can tell us about the people who risked their lives in a wilderness frontier to seek a better future.

But no particular dish lured me on a 500-mile road trip to discover Appalachia’s frontier cuisine. What actually happened is that I saw a sign. Near the western boundaries of colonial-era life in Virginia, a historical marker not far from the town of Front Royal noted that the community “grew along the Great Wagon Road, which stretched from Philadelphia to Georgia.”

I know about the Oregon Trail and some others, but this was the first time I had heard of an ancient travel corridor along the East Coast that, apparently, had been in use for millennia. The long road extending in front of me, I learned, once fed thousands of people in southern Appalachia, men and women who brought recipes and traditions from faraway homelands and melded them to the mountain’s soil, climate, and growing seasons.

With the promise of history underfoot and the likelihood of good meals along the way, I then set out to see what’s for dinner.

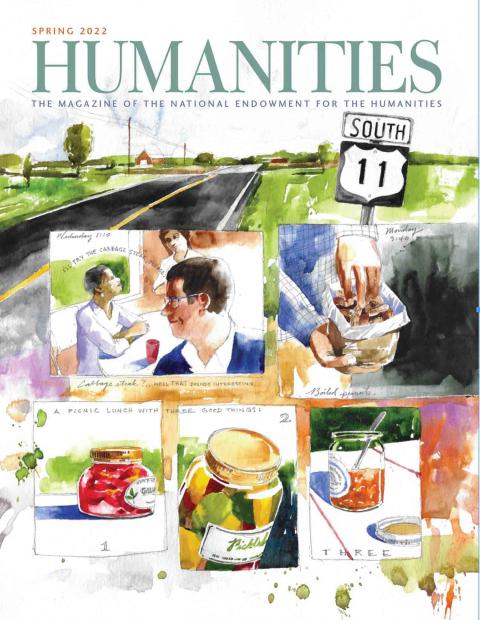

Route 11 in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley seems cut off from the world beyond. Mountains rise in all directions, in shades of faded denim that deepen as the day wears on. Emerald fields of soy and young corn keep company with cow pastures studded with the local bluestone. The Shenandoah River runs alongside, coiled like tightly folded Victorian ribbon candy, providing a source of water as travelers passed through the mountain valley.

Once established, roads rarely move. With time, they tend to become richer in resources. To newcomers, a well-trodden path signals convenience, opportunity, and a better chance of survival.

Part of an ancient network of paths, Route 11 has gone by many names. The Shawnee people called it Athiamiowee, “Path of the Armed Ones,” while the Algonquian named it Mishimayagat or the “Great Trail.” Early on, its paths were used for hunting, later for travel, trade, diplomacy, and warfare. To Scotch-Irish and Swiss-German immigrants arriving from Pennsylvania three centuries ago, it was known as the Great Wagon Road.

As an amateur road historian, I am learning a lot from the Wilderness Road: Virginia’s Heritage Migration Route initiative. This partnership between regional museums and Virginia’s tourism board offers a window into eighteenth-century Virginia. A Google map produced by the initiative highlighted the historical towns I passed through as Appalachia’s immigration story unfolded in the landscape around me.

Historical towns appeared at curiously consistent intervals—about 15 to 20 miles between them. The reason behind this, the Wilderness Road initiative explained, is that 20 miles was the average distance a group traveling by wagon could trek in a single day. Over time, taverns and mercantiles sprung up to serve the constant stream of travelers, and those 20-mile rest stops developed into towns that still exist along the route. The greatest distances were traveled in the winter, when potential conflict with local Indian tribes was least likely. In the spring and summer, immigrants would stop to homestead and raise crops before moving on or settling nearby.

The size of Appalachia all but guarantees variety in its communities and cuisine. The mountain range runs 1,600 miles, or twice the length of California. But in southern Appalachia, waves of Scotch-Irish, German, and English immigrants imparted to the region a distinct heritage and a culinary tradition that chef Kari Rushing hopes to keep alive at Vault & Cellar in Middletown, Virginia.

“Our history here was made by survivalists,” Kari told me. “It’s centered around pickling, preserving, curing, making things last and stretching them. The heart of Appalachian dishes is about preserving history, and ensuring that these concepts and recipes don’t get lost or forgotten.”

The crucible of mountain living, with its longer fall and winter seasons, dictated which foods flourish. Shaded mountain hollows brought challenges far different from those found in the surrounding foothills. Crops had to be hardy, quick to grow, and rich in nutrition. In a cookbook I purchased in North Carolina’s Great Smoky Mountains, author Rose Houk notes, “Food was not a measure of wealth, for everyone ate mostly the same things—common, filling, honest food without pretensions.” The struggle to grow and preserve enough food to eat was near universal for Appalachian settlers, as the names of past communities in the Smokies attest: Poor Fork, Raw Dough, Needmore, and Long Hungry.

In mountain kitchens, the humble cabbage played a variety of roles, fermented in German sauerkraut, tender and laced with bacon in Irish colcannon, or minced into a zesty chowchow, the required condiment to liven up a bowl of beans. It could be squirreled away in root cellars all winter, and even reburied in the ground, root-side up, below the soil’s frost line. Holed up in this way, cabbage could last the entire winter and through spring, offering a welcome crunch of freshness when most vegetables came from the canning jar. Old timers claim that the longer the time underground, the sweeter the cabbage, with a caramelized and intense flavor incomparable to grocery store varieties.

The dishes coming out of chef Rushing’s kitchen echo with generations of Appalachian ingenuity. She serves dinner on frilled porcelain that could have come straight from your grandmother’s cupboard. Half-moon slabs of grilled cabbage fill the plate, a rebellious shade of bright purple that glistens in the restaurant’s candlelight. Chopped herbs and marinated raisins rest in its charred folds, along with a drizzle of agrodolce, a punchy sweet-sour condiment of concentrated vinegar.

Cut with a fork and serrated knife, the cabbage steak borders on animalistic, smoky and rich with a sulfuric edge. The dish might be vegan, but my taste buds are reminded of a slab of beef brisket, smoked low and slow over fragrant hardwood. For families living in the mountains, the similarity to meat was not a coincidence. Cooked with a small amount of pork, cabbage could extend the protein and provide a satisfying meal.

“I feel most people grow up with grilled cabbage steaks, or maybe that’s just an Appalachian thing,” chef Rushing notes with a shrug. “Opening this kind of restaurant in the winter and having your entire concept hinge on seasonality means you’re constantly asking, What do we have to work with right now? And, for better or worse, that’s cabbage.” With the supply chain disruptions and intermittent food shortages that many of us have recently faced, the culinary lessons of Appalachia resonate more than they might have in the past.

Eight hours of driving later, I’m in the heart of North Carolina’s Appalachian Mountain range. Unlike the mellowed ridgeline of the Shenandoah Valley, the Great Smoky Mountains are taller, with deep-shaded hollows that still feel like frontier wilderness today.

A hand-painted sign promising boiled peanuts lures me to Bearmeat’s Indian Den, a shop nestled into the Appalachian forests within the Qualla Boundary. This “nation within a nation” belongs to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and is, technically, not a reservation, though the land titles are primarily owned by the Cherokee people and held in a federal trust. The 57,000-acre property extends deep into the mountains but represents just a portion of their once far-reaching homeland.

Stepping inside, the funk of cured meat melds with the sweetness of the timber cabin walls. Bearmeat’s caters to locals and travelers alike, with shelves of local crafts, vacuum-packed slices of country ham, and baskets of wood-carved toys for children. A stuffed bald eagle spreads its wings in a corner case, near a label stating that this bird met an unfortunate end involving electric lines, and that its possession is federally allowed under Cherokee religious practice.

A Noah’s Ark of mountain foods have been pickled and packed into mason jars. Quail eggs glow bright indigo in beet brine. Green asparagus fills other jars, packed stem to spear without a centimeter to spare. Labels pasted on the jars cite local suppliers and Amish farms, some handwritten and mottled from raindrops long past.

At the end of the shelf, an unlabeled jar seemingly filled with green and yellow confetti catches my eye: golden corn kernels and slivered green beans, summer’s bounty in a pint-sized package. Whoever pickled these vegetables must have believed they wouldn’t need an expiration date.

After a few days of rolling around in the trunk of my car, the jar was ceremoniously opened one weeknight to accompany a frozen pizza. Hardly the most authentic Appalachian meal, but the flavors went well together. The light vinegar tang of the vegetables provided a bright counterweight to the pizza grease.

Farther down the winding road, the Museum of the Cherokee Indian reveals how the uniquely nourishing qualities of corn played a key role in the tribe’s social relationships. During the Green Corn Festival, the tribe came together to celebrate the harvest and establish social balance in the community. It was a time to form alliances between clans, forge trade agreements, and arrange marriages, as Cherokee leaders knew that war was less likely among related tribes. Thanks to the memoirs of Oliver Spencer, a captive with the Shawnee of Ohio during the 1790s, we have an enviable record of that tribe’s green corn feast: dried meat boiled with fish, stewed squirrels and venison, corn on the cob, squash, succotash, roasted pumpkins, cornmeal bread, and cornmeal pudding.

For thousands of years, corn has been a foundation of the Appalachian diet. Archaeologists working in the mountain range have discovered kernels of cultivated corn strains dating back 1,400 years. When the eastern flint corn variety appeared during the Mississippian period (1000–1700 CE), its abundant kernels and nutritional value changed the nature of society. As the Museum of the Cherokee Indian noted, the arrival of corn led to additional leisure time and made it possible to feed and raise more children.

The “three sisters” of corn, squash, and climbing beans may be one of the most valuable combinations to be passed down in Appalachian culinary tradition. The three crops sustained First Nation tribes and early immigrants alike. Grown together in a field, or “companion planted,” each element helps the others thrive. Tall stalks of corn serve as natural poles for the runner bean vines to climb, while prickly low-to-the-ground squash leaves shelter the base of the corn stalks from sun, erosion, and pests.

When consumed together on a plate (or hollowed-out gourd), the body digests the amino acids of corn, squash, and beans as a full protein. The trio could also be preserved and eaten into late February, a time known by some Algonquian tribes as the Full Hunger Moon, given the difficulties of hunting in deep snow. Strips of squash were dried and pounded into meal, and then stored throughout the winter, along with dried beans and corn. When hunting was difficult, tribes could rely on the three sisters for their protein.

As the network of paths skirting southern Appalachia began to widen in the 1600s, the increasing streams of newcomers touched off years of conflict, broken treaties, and tribal concessions that ultimately pushed tribes out of their native lands as European immigrants homesteaded Appalachia. But the three sisters would remain long after the Cherokee and other tribes were forced to relocate west of the Mississippi River.

Plant life itself offers yet more ways into the history of food. Ancient seeds are today gracing Appalachian gardens through the efforts of seed-savers like Kevin Welch, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Welch notes the tribe’s loss of wild food practices in research by the Renewing America’s Food Traditions alliance. “Throughout the historically modern 1800s and early 1900s, there seems to have been a view held by richer tribal members that eating or retrieving resources from the woods was a requisite for poor Indians,” Welch writes. To help the Cherokee regain their food heritage, he founded the Center for Cherokee Plants in 2007 and runs a seed exchange program that propagates threatened heirloom varieties.

Seed exchange participants agree to two main conditions: They return 10 percent of their initial yield back to the center, and they grow their heirloom varieties in isolation. This is a particular concern for those growing corn and beans, which form genetic hybrids easily. The geography of the Appalachian range helps seed-savers on this mission. Tucked into valleys, small gardens are protected by the high mountains from contamination with other varieties. Ever so slowly, heritage crops like the Lazy Housewife bean, Bloody Butcher corn, and Cherokee Purple tomatoes are returning to Appalachian dinner tables.

For European immigrants and colonial Americans, corn and beans were equally essential in building a life out of the frontier wilderness. Farmers accustomed to wheat’s labor-intensive practices in the old country were quick to adopt corn, which could feed a family and stay edible over longer distances of travel and exploration. Immigrants embarking on the Great Wagon Path with a sack of corn had food for themselves, nutritious feed for their livestock, and seed for future plantings.

Survival, independence, and growing one’s own food go hand in hand for many living in the mountains. “For us, as families whose only livelihood was subsistence farming supplemented by a little hunting, trapping, and ginseng digging, gardening was not merely a hobby,” notes farmer and seed-saver Bill Best in the cookbook Victuals by Ronnie Lundy. “Good gardens ensured eating well until the next ones started yielding.”

A flourishing garden and well-stocked larder were a form of independence for Appalachia’s African-American communities. Following emancipation, Black men and women moved to the mountains to escape racial violence and seek opportunity, notes Black in Appalachia podcast hosts Enkeshi El-Amin and Angela Dennis. Mining companies recruited African-American sharecroppers from the South to work alongside white miners and Eastern European immigrants. The conditions were often dangerous, but the pay and treatment could be better than elsewhere in the Jim Crow South. Gardening was another way to thrive in these circumstances. In towns run by the coal companies, food grown in the kitchen garden translated into less debt owed at the company store.

For Ophus Hethington, chef de cuisine at Benne on Eagle, food offers a way to share Black heritage with broader audiences in Appalachia. The catalyst for him was an episode of the Mind of a Chef television series, where acclaimed Virginia chef Sean Brock traveled to Dakar, Senegal, to examine the impact of the transatlantic slave trade on Southern cuisine.

Brock visited waterside fish markets and explored how the flavors and methods of Senegalese cooking connect historically to low country favorites. “Everything that’s on a plate is history,” chef Hethington said. “The idea that red red [Ghanian black-eyed pea stew] and jollof rice are the great-grandparents of what most South Carolinians eat, and that gumbo is derivative of stews you’d find in West Africa. . . . To me, it’s a history lesson.”

Benne on Eagle is tucked into a historically Black neighborhood in the lush mountain town of Asheville, North Carolina. Under Hethington’s leadership, the restaurant has focused its menu on reintroducing the African diaspora into Appalachian dining.

Hethington grew up eating Haitian griot in southern Florida and now features the dish at Benne. In his version, chunks of pork shoulder with crisped edges sit on a bed of creamy corn polenta, finished with a scattering of pikliz—a punchy Haitian pickled cabbage condiment. More than the name of a dish, griot also refers to the artist-diplomats of West Africa, a kind of professional and social role that originated in the West African nation of Mali in the thirteenth century. These individuals are the musicians, oral historians, and genealogists of a village, responsible for keeping the community’s heritage and traditions alive. It’s a role that chef Hethington has reinvented in the kitchen.

“It’s about exciting people to try new things and understand the depths of Black people, Black food, and, even more so, our place in the history of this world.” At Benne, chef Hethington balances familiar preparations with African ingredients that seem slightly unfamiliar—until the light bulb flicks on and historical connections are revealed. “Knowledge is empowerment for everybody,” he says.

The restaurant’s name pays tribute to the benne plant, whose seeds were initially brought over from West Africa and cultivated in the private gardens of enslaved Africans. Today, benne—also known as sesame—seeds are found in many southern dishes. This ingredient underlines southern Appalachia’s history with slavery. The old narrative that the region’s steep mountains and impoverished communities couldn’t sustain slave-holding farms has largely been disproven. Looking at county tax lists, census manuscripts, and slaveholder records, sociologist Wilma Dunaway estimates that nearly one in five Appalachian households held slaves.

Early mining and timber operations purchased enslaved men to work the mines and forests. Enslaved livestock drivers led cattle and pigs into Appalachian forests to fatten them up before heading to southern markets. Summer resorts hired enslaved women and men to serve as cooks and housekeepers for the northern industrialists and southern plantation owners who sought out the cool mountain air.

In the isolated mountain hollows of Appalachia, the gardens planted by enslaved men and women still exist, grown over and forgotten. “Although not originally African, peanuts grown in Africa would cross as food for enslaved captives on slave ships and would arrive in early Virginia; those original goobers marched with enslaved people into the mountains where goober patches can still be found even in heavy clay soils,” notes food historian Michael Twitty. Sweet potatoes, watermelon, and black-eyed peas traveled from the nexus of the West African-Caribbean slave trade to the mountains of North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia, where they were cultivated by enslaved and free people. The foodways of the West African-Caribbean slave trade became Appalachia’s foodways.

Finishing my meal at Benne, I ordered Daisy Mae’s sweet potato pie. The slice delivered by the waiter could have been pulled directly from the dreamlike nostalgia of Wayne Thiebaud’s dessert paintings. A perfect wedge of sweet potato custard on browned crust, sprinkled with peanuts and benne seeds. Fragrant notes of nutmeg and allspice are threaded into the silky sweet potato puree. It’s creamy and earthbound, and more than a touch reserved in its sweetness. Without knowing the backstory, its taste seems ancestral, continued from a place of love and respect. As it turns out, the recipe is a tribute to chef Hethington’s grandmother, who always brought her famous sweet potato pie to family gatherings before her passing in 2019.

“For me, it’s always important to draw upon those connections,” Hethington notes. “As corny as this may sound, I’m cooking through my ancestors’ spirit or dreams.” That awareness, that each dish passed on to us carries the experiences of our ancestors, is at the heart of how food can be used to link strangers to a shared humanity.

Whether we realize it or not, the foods we eat are seasoned with the memories and traditions of the generations that preceded us. Sometimes these connections extend back millennia, like a jar of pickled corn and beans, and oftentimes they tell of survival and resilience, like chef Rushing’s grilled cabbage. In a slice of chef Hethington’s sweet potato pie, the past is recalled, savored, and shared. It’s a deeply human approach to food and history, and, just like Daisy Mae’s sweet potato pie, a very satisfying end to a long journey through Appalachia.