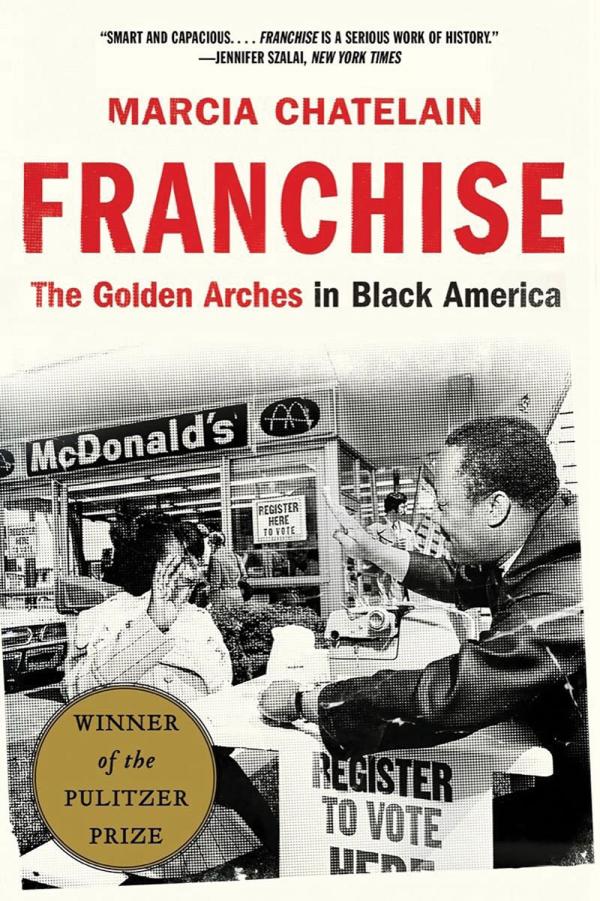

Marcia Chatelain is a professor of history at Georgetown University and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, which also won the Hagley Prize in business history and the Organization of American Historians’s Lawrence W. Levine Award.

Supported by an NEH research fellowship in 2017, Franchise examines the some-times fraught history of the fast food giant McDonald’s in Black communities and the related history of various attempts to empower African Americans through investment in Black-owned businesses. Chatelain is also the author of South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration, published in 2015.

HUMANITIES: How did you first become interested in the history of McDonald’s, and when did you connect that to the larger story of civil rights history?

MARCIA CHATELAIN: One thing I observed growing up in Chicago is just how often African-American cultural events were shaped and sponsored by the influence of Black McDonald’s franchise owners. Whether it was a back-to-school parade or local programming around the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, there were a lot of Black franchise owners who were involved in the cultural life of Black Chicago. I found it really fascinating that so much of African Americans’ relationships to McDonald’s was outside the bounds of a consumer relationship.

Then, in the early 2000s, there was growing concern about health and nutrition and the impact of fast food on communities of color. I started to think about the need to historicize that relationship, and ask, If we historicize the relationship, does it change the nature of the interventions that people were making around the issue of food and health?

HUMANITIES: What was McDonald’s like in its earliest incarnation?

CHATELAIN: It is hard for many of us to imagine a world without McDonald’s, but there was a time when McDonald’s was new to communities, when it was an unknown quantity for people who were exercising their consumer freedoms for the first time.

From my perspective, McDonald’s represents mid-century consumer culture as well as the political and racial climate at the time, because so much of what creates the image of McDonald’s in the 1950s is suburbia, car culture, and freedom of mobility, all experiences and ideas that are off-limits to African Americans of the time.

Then how do we understand McDonald’s as not just a manifestation of the mechanization of food production, leisure culture, dining out, and cars, but also as a reflection of policies around race?

Also, consumer citizenship becomes so important in the 1950s. It’s such a strong symbol of what it means to be an American. What does it mean when every American doesn’t become part of that experience?

HUMANITIES: Who is Ray Kroc, and why is he important to the story of McDonald’s?

CHATELAIN: Ray Kroc was the head of McDonald’s who transitioned it from a small southern California chain to the franchise we know today. He originally sold milkshake makers to the founders of McDonald’s, Richard and Maurice McDonald, and he was captivated by their business model and he made a move to acquire it. It is interesting because there are so many books written about McDonald’s and whether he’s the great founder of the McDonald’s franchising system or the evil genius behind the burger business. I think, at the core, Ray Kroc was a true American capitalist. He understood that for McDonald’s to expand and be profitable, it had to shape-shift with the times.

While he envisioned it to be the car hop and preferred dining location for white suburban America, in the late ’60s he realized that that vision wasn’t going to be sustainable in some parts of the country, and so he shifted. It wasn’t a radical, political shift, but it reflected an understanding that you grow your business through marketing and branding and creating affective bonds with consumers. I think that continues in a lot of the big brands that we have today.

HUMANITIES: When did McDonald’s and Black consumers first find each other, and was it love at first sight?

CHATELAIN: It’s more of an awkward relationship. African Americans don’t really become franchisees, and McDonald’s doesn’t begin saturation marketing to African Americans until the late ’60s, after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

Just as we hear calls for more Black business ownership today, in the late 1960s that same pivot toward Black ownership and supporting Black business helped galvanize sensibilities after the death of King. McDonald’s really capitalized on that moment and suggested that they would expand in the urban core as a response to the unrest that happened after King’s death.

HUMANITIES: You talk a lot about Black capitalism in your book. What is it? Is it a catchphrase, a government program? Is it both?

CHATELAIN: It’s both, a little bit of Column A and a little bit of Column B. Black capitalism is an ideological position that says in the absence of a state that is going to secure civil rights the next best thing may be for Black communities to enrich themselves through business ownership and through an infusion of capital that circulates within the community.

At various points, from the nineteenth century to today, we hear people evoke ideas of Black capitalism. But, in the late ’60s, it is especially important. People want to see if Black economic power is going to be the next step. Everything is on the table and everything is possible. You have a Republican president, Richard Nixon, proclaiming he’s pro-Black capitalism. You have celebrities like Wilt Chamberlain and James Brown supporting Black capitalism. You have local communities that are starting to see the possibilities of opening businesses to sustain themselves.

It was really important to me not to mock the ideas that came out of this period, though we have the hindsight and knowledge to know what worked and what didn’t. From the perspective of 1968 or 1969, there is a world of possibilities, right? If you found the right mix of investments, if you brought just enough capital and grew enough businesses, maybe you could actually respond to the deep racial and social inequalities of the time.

HUMANITIES: One of the more gripping episodes that you explore is a controversy in Cleveland in the 1960s. I wonder if you can sketch that conflict and say how it figures into your book.

CHATELAIN: The Cleveland controversy is one of my favorite chapters because it shows the different ways that people could align under the umbrella of Black capitalism but had very different ideas of what it’s supposed to do.

In Cleveland, there was a boycott of McDonald’s in the predominantly Black east side, and it wasn’t a boycott based on refusal of service, which we are used to in the traditional civil rights narrative. It was because Black Clevelanders believed that if McDonald’s was going to make money in their community, then they should be franchised by Black people.

The questions of who gets the franchise, who gets to profit, and what should happen to those profits laid the foundation for some of our conceptualizations of corporate social responsibility. I am thinking of what it means for corporations to invest in communities, and what it means for communities to be able to set the terms on how businesses engage.

All of these questions that are now common sense for corporate America were being figured out. And the Cleveland protests showed these different visions of what Black success should look like. At the same time there is a big local political story. A newly elected Black mayor wants to keep his job and has to, on the one hand, show his solidarity and support for Black protests, but he also has to show white business interests and white people in Cleveland that he can respond to their needs.

That moment in many ways foreshadows the political climate of the ’80s and ’90s. What does it mean for Black electeds to be able to represent all people, and what does it mean for local communities to set the terms of engagement with corporations?

HUMANITIES: That was also one of my favorite chapters.

CHATELAIN: It’s so weird. Everything about it is so strange, too. There was a Jonestown connection. You don’t know who’s on the take. It’s such a bizarre kind of thing, and I tried to be as respectful as possible. But there’s just so many weird elements about it.

HUMANITIES: Is there a kind of ethics of storytelling behind how you write?

CHATELAIN: The way I write is reflective of the way I teach. I always try to be fair to all the parties involved and to remember that I know how the story ends; they didn’t. I try not to use a present-based lens to evaluate whether a person made the right decision, but it’s also important to point out that in some moments people actually had real choices to make. The question then becomes, How do we evaluate the choices they make?

I don’t like the kind of historical argument that says, well, this was okay because in this time it was okay. Well, there’s a lot of evidence that there have been robust debates about all sorts of moral choices, whether it’s slavery or the subjugation of women or the institutionalization of people with disabilities. There’s always a counter-voice saying, I don’t think that’s a good idea.

Yet it’s also important to think about the landscape and the context in which decisions are made, so we can’t say, wow, it was really foolish for someone in 1972 to think a McDonald’s was going to save the community. The more important questions, I think, are, What were people striving for? What could they imagine? And what was available that contributed to making this choice?

I think it’s important for historians to really punch upward toward the structures that truly imperil people, and then try to move closer to the thinking of the individual people who are gripped in a moment and have to make a decision.

HUMANITIES: What are some of the challenges of writing a social history that is so intertwined with an existing corporation with a very real interest in how it’s perceived?

CHATELAIN: Corporate history is always really hard. In this case, I didn’t have access to the McDonald’s archives. But one of the things that I’m really proud of, with this book, is that I showed you don’t need institutional access to write stories. Sometimes you just need a different lens and a different viewpoint of how you’re telling that story.

Centering the Black experience within the history of McDonald’s brought tons of archival information to the surface. So many books already talk about McDonald’s as the product of southern California’s suburban culture or as the story of a midwestern business ethos or just the story of Ray Kroc, and in those tellings all of these other factors get erased. It’s important for historians to think about who is at the center of the story and to consider how that is going to animate sources.

HUMANITIES: In the late 1960s and 1970s, McDonald’s made significant progress in learning how to market to Black consumers. Who was responsible for the shift, and how did McDonald’s adjust its messaging?

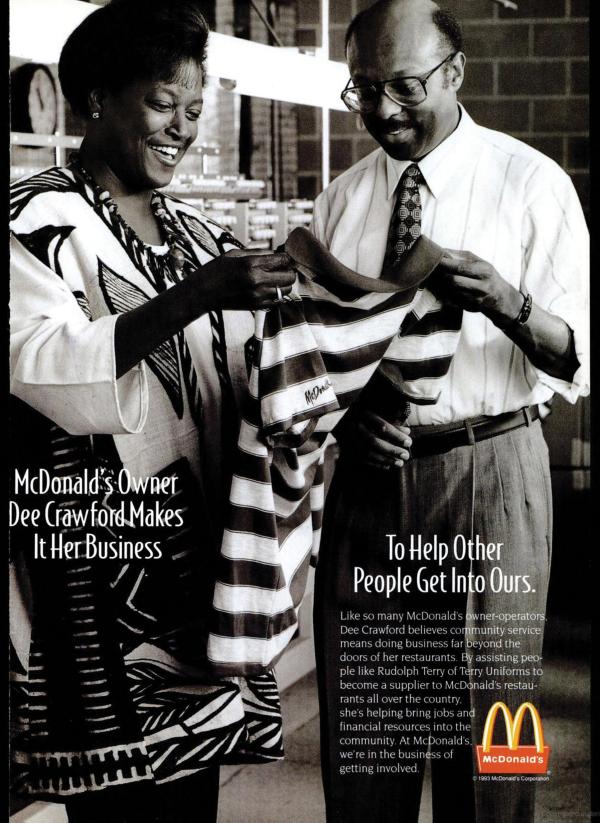

CHATELAIN: Two important forces led to that change. One was the growing influence of Black franchise owners who were financially quite successful and able to leverage their position to say there needs to be more concerted efforts to market to the communities that are contributing to market share. Around the same time, we see the rise of a kind of Black or multicultural advertising and marketing that really exploded in the late ’60s and early ’70s as companies were in a period very similar to this past year. It was a moment of racial reckoning and of recognizing communities that had been either ignored or stereotyped or mischaracterized.

So we see Black creatives and researchers coming into their own just as McDonald’s recognizes the efforts of the franchise owners and says, okay, let’s invest in some targeted marketing. And this really reverberated. Not only did Black market researchers contribute and benefit, so did Black statisticians and African-American ethnographers. They now have an industry to enter. And then in the advertising side it’s all of the visual artists, all the actors, all the actresses, the models and the dancers and the singers who appear in commercials. It really creates a growth industry for people who otherwise did not have access to the industries of their choosing.

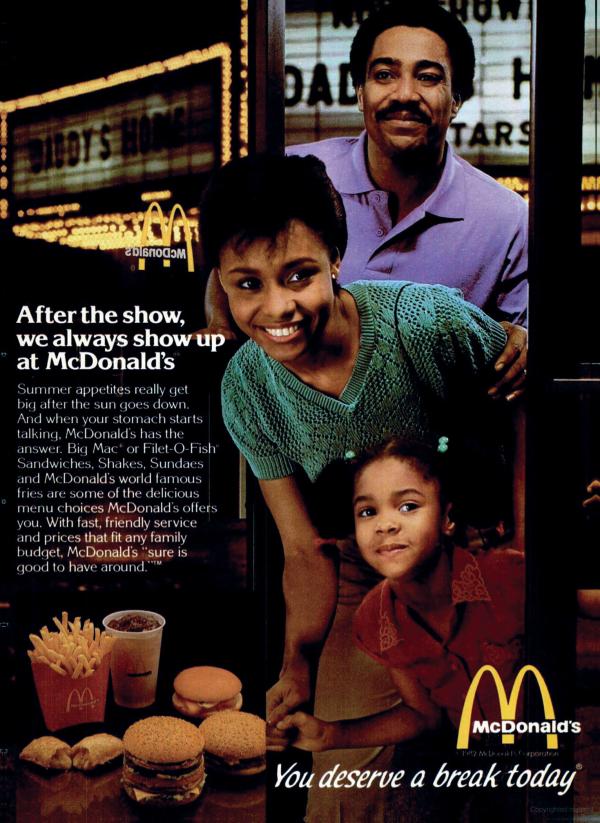

HUMANITIES: I was particularly interested to learn that the tagline “You Deserve a Break Today” did not resonate with Black consumers. Why did it fail?

CHATELAIN: “You Deserve a Break Today” is one of McDonald’s successful campaigns, but “break” had different meanings in African-American communities. White consumers saw McDonald’s as a treat, as a way of spending time with the family, and a leisure activity. Black consumers saw McDonald’s differently.

One of the critiques of “You Deserve a Break Today,” after McDonald’s tried to use that slogan in an ad featuring African Americans, was that for African Americans in the late ’60s and early ’70s, there were no breaks to be had. Tom Burrell, the head of the advertising agency Burrell Communications, took over the endeavor and his team took a different approach to marketing to Black people. There was the unfinished business of civil rights, the growing gulf between the Black middle class and the Black poor, and the unemployed. McDonald’s was not considered a break but rather a consistent presence in communities, a source of food. This idea of a “break” just didn’t really capture how people felt in the moment.

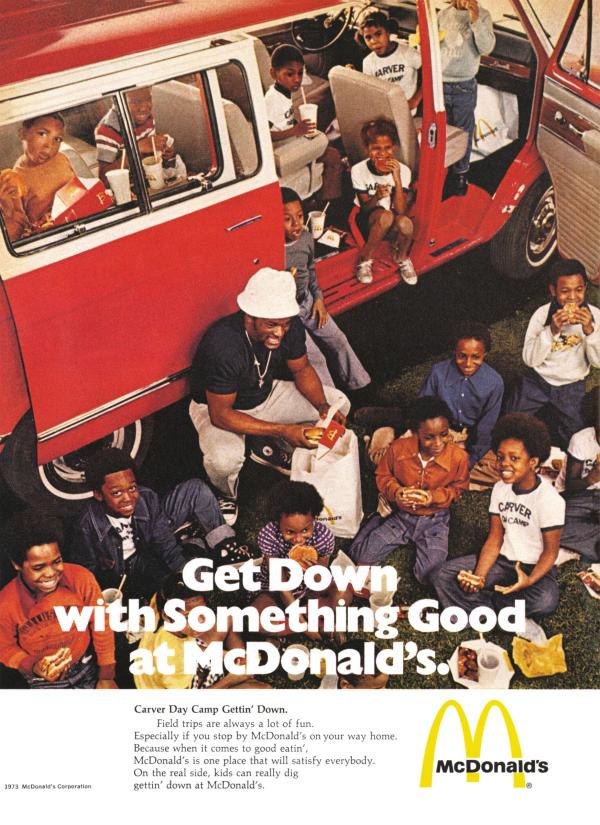

McDonald’s then created a campaign called “So Good to Have Around,” as if to say, We’re here. Another was “Get Down with Something Good at McDonald’s.” Both express this idea that McDonald’s is a regular presence. You pop in, you know what to expect. And one of the ways that I read this marketing appeal, though some of it may seem uncomfortable in 2021, is that McDonald’s was telling Black consumers, Hey, this is not going to be stressful, this is going to be easy. And I think that was a reference to the ways that dining was a source of stress and anxiety for African Americans for such a long time. With its new campaigns, McDonald’s was trying to say this will be an easy experience, there’s no fear of violence, there’s no unspoken rules, you just show up as you are.

I think that’s powerful, and I think that’s insightful about what consumer experiences were like for Black people well into the late 1960s.

HUMANITIES: In your chapter on Portland you write about the Black Panthers, who were involved in a controversy with McDonald’s, and, as you show, were also working hard to provide breakfast to poor kids. There’s more to the story in Portland, of course, but I wonder if you think we are seeing a reevaluation of the Black Panthers in the age of Black Lives Matter.

CHATELAIN: Oh, that’s a great question. I think what we’re seeing is a reevaluation of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense partly because of the Movement for Black Lives. I think also, with the rise of mutual aid networks during COVID, that the example of the free breakfast program and the food programs of the Black Panther party have become important today in some cities, as grassroots collectives are working to take care of themselves.

But I think the reevaluation of the Black Panthers is the direct result of a generation of scholars who have gone back and really tried to challenge this notion that there is King’s way of leading the movement and then everyone else’s: violence versus nonviolence. So I think some of those walls have been broken down.

The last part I’ll say is that work like Alondra Nelson’s book about the Black Panther party and health care and the amount of scholarly work that is really specific to the acts of the Black Panther party has been helpful in taking a more holistic look at what this movement was about and understanding that it wasn’t anti-institutional to its core. It was actually very structured, even pro-establishment. Anyway, the scholarship has changed, and when the scholarship changes, it allows us to take a bigger view of any historic moment, and that’s really exciting to see.

HUMANITIES: How do you summarize the overall historical argument of your book?

CHATELAIN: Franchise is about the moment after King’s assassination when there was a national question as to what the direction of Black freedom struggles would be, and many people answered that by saying the direction would be that of business and industry. So this is the story about how McDonald’s benefited from a pivot in the civil rights struggle.

HUMANITIES: This may seem like a silly question, but is the title a pun?

CHATELAIN: In a way, it is. My editor came up with this title. Originally the book was supposed to be called “Burgers in the Age of Black Capitalism,” but that was considered too academic and shelved because of a fear that people wouldn’t know what Black capitalism was. I thought it was clever.

Another title was “From Sit-In to Drive-Through,” which I felt was maybe the most pessimistic kind of title, going from the gravitas of the sit-in to the debasement of the drive-through.

And then finally my editor said “Franchise,” and I thought that was perfect because the picture on the cover is this young woman taking the oath of voting, and I thought, yes, this is it, this idea that the struggle for civil rights is about the ballot box, and then it becomes about getting a McDonald’s in your community.

So it is a pun in that sense. A lot of people think the book is about voting rights, and it is not.

HUMANITIES: One of the events you dive into is the 1992 Los Angeles riots, and the story is often told that the McDonald’s franchises in Los Angeles were spared because of their value to the Black community. Is that the conclusion you draw from revisiting that history?

CHATELAIN: I think it’s the most outrageous claim that I’ve ever heard from a corporation. I initially wrote this book because of that claim, because I thought it was such a strange thing to say, and I tried to verify the claim by going to the archives of the University of Southern California. I think it was the Webster Commission that was supposed to say what happened in L.A., and I could not get a good answer on it.

But what I soon discovered is it didn’t need to be true, that by 1992 there was this sense that McDonald’s was kind of a champion of Black people, and the fact that this is repeated by so many different types of people showed that McDonald’s had done the ideological work. Even if there were reports of damages at McDonald’s in the press in the days after, it didn’t matter. McDonald’s had anchored itself into a relationship to Black America so thoroughly that this claim seemed plausible, and people would repeat it.

Remember this was the ’80s and ’90s, before people got very good at corporate social responsibility/racial reconciliation talk. People would just say these really outrageous things, and they could because there wasn’t a script yet. I don’t think anyone would make that kind of claim today. They would couch it in a different way, like “McDonald’s is a member of the community, and community members respect how community-minded we are because we are a community.”

HUMANITIES: What are some other underexplored areas of twentieth-century business history and social history where you’d like to see scholarship and storytelling go?

CHATELAIN: I would love to see more research on the Black capitalism of the ’70s that actually worked. This history is sometimes painted with a broad brush: Everyone had these ideas, they were so idealistic but silly and none of them worked, and so we kind of laugh or scoff at that period.

But I would argue that McDonald’s worked, and this was an extension of Black capitalism. For the African Americans who entered into the franchising of hotels, it worked for them too. For the people who were able to be part of those negotiation teams, with groups like the Urban League and the NAACP, Black capitalism actually worked for them.

But there is a way that that history gets kind of bifurcated into the silly community-based things that people laugh at, like, Are you really going to manufacture soap that’s going to change Detroit? Probably not. But what you do see is the corporatization of Black leadership that is dependent on some of the ideas of Black capitalism, like the solidarity of Black buying power and the importance of Black business.

All of these gestures toward Black partnerships and collaborations, these things kind of get folded into these larger corporate enterprises, and they work. I think that we need a little bit more research about the Office of Minority Business Enterprise that started with Nixon and that was kind of absorbed into some of the Small Business Administration goals. Like, What does it mean for the federal government to underwrite a certain idea of what economic development looks like in Black communities?

HUMANITIES: Speaking of history projects, you are a part of a fascinating project at Georgetown to reexamine its history of slavery, the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation. It’s really one of the most remarkable projects in the country of its kind.

CHATELAIN: Yes. It’s kind of like what I talk about in the book. We are at a very specific moment, and I think that after the killing of Freddie Gray, the deaths at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, and rise of Black Lives Matter, Georgetown University was not only internally grappling with how they were going to discuss and understand their history with Catholic slaveholding in the United States, but there was also this external space in which there were a lot of questions. These were not only about racial justice but also some of the artifacts or objects that we still have that tell a truncated story of slavery.

In the case of Georgetown, it was about these residence halls that had been named for some Jesuits who, in 1838, sold 272 people that the university had owned. That process was really fascinating to me. I had gone to Brown for my PhD, where Ruth Simmons was the first African-American president of an Ivy League school. One of her first priorities was to think about Brown and its relationship to slaveholding. And she did it by herself. Other institutions wanted nothing to do with this type of work.

This is before social media, but it was on Fox News, and it was really lambasted by conservative media. But from the perspective of 2015, when people were having conversations about Calhoun College at Yale, and asking what exactly are we doing with Confederate monuments, the time was perfect for this type of conversation at Georgetown’s campus.

As a historian, you hope that people learn some history from when you write or make a speech. Rarely do you get to be part of a project and observe people coming to a fuller understanding of who they were and who they are. Georgetown engaged a group broadly called the Descendants who were the descendants of the 272, and I got to watch in real time as people met for the first time and realized they’re related. Other people came to understand why their family had always been Catholic. Others who grew up in Louisiana but had always heard these stories of their roots in Maryland learned the truth.

Watching that unfold is an amazing thing, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a scholar. And it was equally incredible to watch the ways that disagreements and contentions emerged. What are the responsibilities of an institution to the descendants? A lot of people have a vision of what restorative justice is or what reparations are, but what do they look like exactly? What do they look like in the context of higher education?

So this was an experience I never anticipated. I’m not a nineteenth-century scholar, but by virtue of where I worked, my understanding of, particularly, Black Catholics, and my presence at a particular moment, I got to see something unfold that was really remarkable.

HUMANITIES: Thanks so much. This has been great.

CHATELAIN: I was glad to do it. Can I say one more thing?

HUMANITIES: Sure.

CHATELAIN: I’m so grateful for NEH. If I hadn’t gotten that fellowship when I did, this book would have never gotten done. My situation was bad. I had no time. I was being pulled in a million directions right before this.

I had applied for NEH grants in the past and did not get them but always was able to use the substantive comments from the review process, and I always encourage scholars to reapply.

But at the time that I got the NEH, it was just the fire that I needed because it propelled me to sell the book, to put out a proposal, knowing that I would have that time off at the end of the semester. It was just so exciting to be able to submerge myself in the writing of this book.

I completed the first draft of Franchise right at the end of the fellowship period, and it made all the difference. My book is about vigilance, about making sure that we have a public good and public resources for people to live lives of meaning, and I think NEH is an example of such a public good and a public resource in the world of scholarship.