Few early twentieth-century authors of crime and detective fiction are as well remembered today as Samuel Dashiell Hammett (1894–1961): author of The Maltese Falcon, supposed inventor of the hard-boiled detective genre, alcoholic and serial adulterer, not-so-secret lover of the playwright Lillian Hellman, and (depending upon your political persuasion) Communist activist or martyr to liberal democracy.

A literary legend, Hammett has been the subject of numerous biographies and works of scholarship. His life has been fictionalized by multiple novelists and one high-profile filmmaker (Wim Wenders). He has been the subject of a San Francisco sightseeing tour; and today travelers can choose from two Hammett-themed guidebooks to the northern California city where the author briefly lived.

Although the Hammett legend has been built up considerably in the decades since his death, it is not a posthumous creation. Its mythic dimensions were crafted by Hammett himself as an early form of authorial branding. A talented writer, shrewd businessman, and sophisticated reader of the law, Hammett recognized early in his career the advantages of having a romantic backstory. His stories were valued all the more highly for appearing to be products of an unruly genius. Such unruliness, however, was largely for show. Ultimately, Hammett’s success had less to do with his wild lifestyle than it did with his sober, even calculating, work as a creator, licensor, and salesman of intellectual property—what I call “an IP entrepreneur.”

What do I mean by this term? The word entrepreneur refers to a person who takes on the financial risks associated with owning and running a business, especially when that person is the founder of said business. From an economic perspective, we might also say that the entrepreneur discovers unrealized profit opportunities and, by orchestrating the material, financial, and social interactions necessary to realize them, teaches other market participants how to see them.

Authors and writers can be said to become entrepreneurs after they have completed a literary or artistic work, which, once copyrighted, becomes a special form of property that must be actively managed if it is to generate profit. Most authors rely on someone else—a publisher, an agent, a business manager—to manage this property. But some, like Hammett, take on this task themselves. Indeed, for a few, the task of exploiting the copyrighted property comes to dominate and define the author’s creative labor. When this happens, the author’s economic function more closely resembles that of the business entrepreneur in the economist’s sense than it does that of a creator in the humanistic sense.

Hammett’s first success as an author and IP entrepreneur came in the 1920s, with his creation of one of the first hard-boiled series detectives: an unnamed investigator or operative referred to as the “the Continental Op” or “the Op” for short. The Op stories were stand-alone works published in the pulp magazine Black Mask, with few repeated characters, no persistent plot threads, and almost no textual memory. Their hero lacks family and relations, interiority, long-term goals, and even the most rudimentary backstory. More important than character were the series’ wry, laconic tone, fast pace, emphasis on violent action, and pessimistic—or, if one prefers, realist—worldview.

By 1928, the book rights to the two novel-length Op stories, The Cleansing of Poisonville and The Dain Curse, had been acquired by the publisher Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., under a three-book contract negotiated directly with Hammett, which—as was typical of a writer’s first contract with a major publishing house—granted Hammett a royalty but no advance, a 75 percent cut of future sales of motion picture rights, and a 50 percent cut of broadcast and stage rights. As was also typical, the contract stipulated that copyrights for the works would be secured in Knopf’s name.

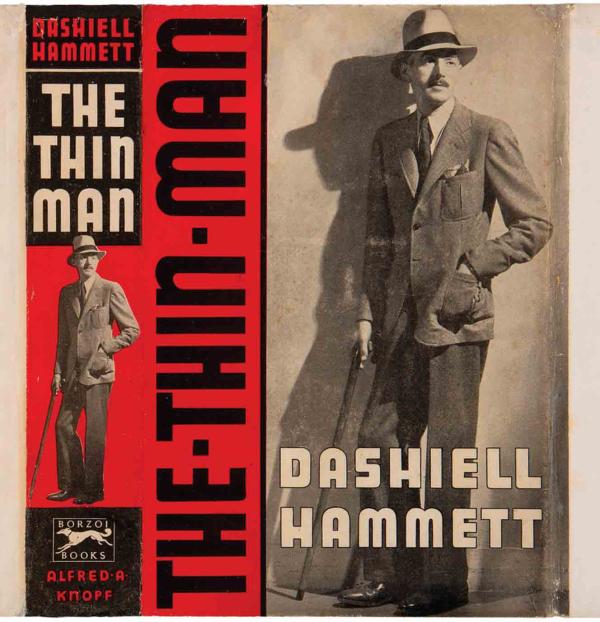

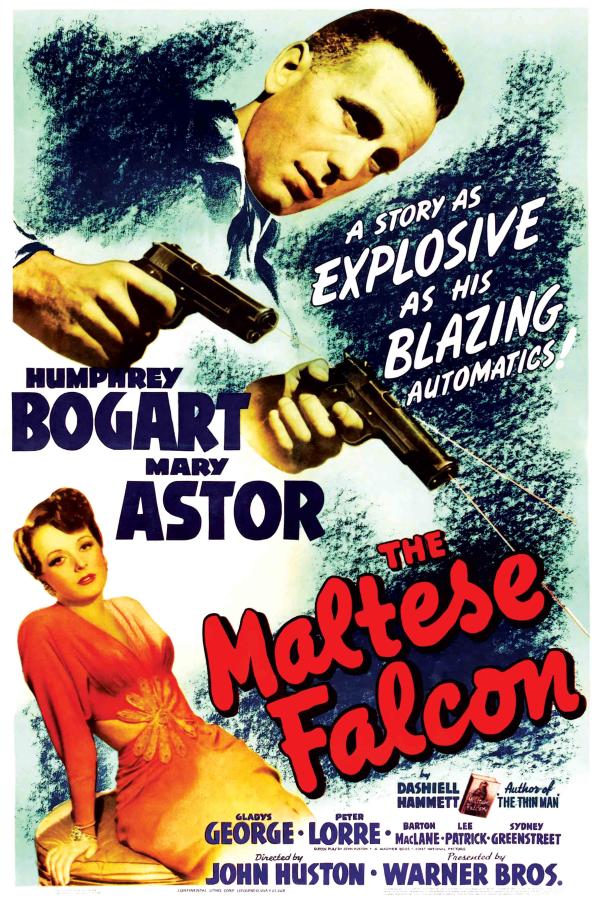

Hammett published his third novel, The Maltese Falcon, in 1930. Within a year, he said goodbye to the world of pulp fiction and became a literary celebrity, regularly feted by Hollywood studios, which routinely licensed his work and hired him as a screenwriter. In abandoning the pulps, Hammett likewise abandoned the series detective. With each new novel, he introduced a new protagonist and social milieu. These included Sam Spade, a tough but ethical private eye operating in San Francisco in The Maltese Falcon, and Nick Charles, a retired private eye and heavy drinker living in New York City with his wealthy wife Nora in The Thin Man. Altogether, four of Hammett’s novels were made into successful films in the 1930s—the first two by Warner Bros., the third by RKO, and the fourth by MGM.

Essential to Hammett’s success was not simply the quality of his fiction but also the impression, carefully cultivated by Hammett since his earliest days as a pulp writer, that his protagonists were all thinly veiled versions of himself. Having worked briefly as an operative for Pinkerton’s National Detective Service in the years immediately preceding and following World War I, Hammett routinely emphasized, in a variety of forums, the real-world basis of his detective fiction.

How much detective work Hammett actually experienced during his time at Pinkerton’s is impossible to determine, but editors, marketers, and interviewers happily took him at his word, and the novels themselves encouraged these pseudo-biographical associations. The Maltese Falcon’s Sam Spade shares the same first name as Hammett and is described in language that could describe Hammett himself. Nor did the day-to-day details of Nick Charles’s life as an aging, drink-happy person of means in The Thin Man appear all that different from that of Hammett’s days and nights at the time of the novel’s publication, a fact underscored by the use of Hammett’s picture on the dust jacket—not as a photo of the author on the back flap (a practice that was, in any case, quite rare in the 1930s) but as a photo of (ostensibly) Nick Charles himself.

With the publication of The Thin Man at the end of 1933, Hammett ceased writing prose fiction and began devoting most of his energy and attention to IP entrepreneurship, banking on his own celebrity to help exploit the fictional works he had previously created. His first big success came in 1934, when MGM released its version of The Thin Man, starring William Powell and Myrna Loy. The film’s extraordinary success at the box office persuaded MGM to acquire from Hammett both the rights to a second film—eventually titled After the Thin Man—and an original story for it. When this film also proved a success, MGM purchased the rights to The Thin Man outright from Hammett and his publisher for $40,000, leaving only the print publication rights and radio rights behind. By the time the third film, Another Thin Man (also based on an originally commissioned story by Hammett), had left theaters in 1939, MGM was in possession of one of the hottest film properties in Hollywood and Hammett himself was widely seen by those in the entertainment industry as a hot commodity.

Leveraging his association with both Thin Man films and Warner Bros.’s third Maltese Falcon adaptation (starring Humphrey Bogart), Hammett moved into radio licensing. A popular radio series based around the Nick and Nora characters launched on NBC as The Adventures of the Thin Man in 1941, running through 1950. The Adventures of Sam Spade began its six-year run in 1946. And The Fat Man, which followed the detective work of a corpulent private eye seemingly based upon the overweight antagonist of The Maltese Falcon, premiered in 1946 on ABC, where it remained until 1951. (Universal also released a film version of The Fat Man in 1951.) Although these shows sometimes used Hammett’s name on the air and occasionally based their plots on short stories he had written, Hammett had no direct involvement with them beyond the initial pitching process and licensing negotiations.

As the 1940s drew to an end, Hammett was drumming up interest for a broadcast series based upon his early Op stories, had entered initial discussions with a newspaper for a Sam Spade comic strip, and had begun rooting around in his older pulp fiction for more properties to develop. “I’ve a couple of other radio or television ideas—based on characters invented in the dim past—in more or less formative stages,” he explained in a letter to his oldest daughter in 1949. By the end of 1951, however, the radio shows had gone off the air, the deals had dried up, and Hammett’s intellectual property had become, in practice, worthless. The abrupt reversal of fortune was a consequence of Hammett’s refusal to testify in a 1951 case related to the activities of a supposedly Communist political group. For this refusal, he was found in contempt of court, imprisoned in a West Virginia jail, subsequently investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee, and blacklisted.

In the late 1940s, however, Hammett’s properties were still of significant value, and Warner Bros. saw considerable potential in the further exploitation of its rights in The Maltese Falcon, which included not only film rights but also radio and television rights. Indeed, the radio rights alone were proving to be lucrative for the studio, which licensed at least five radio adaptations of the novel before 1950.

Despite the obvious value of these radio rights, however, Warner Bros., still at this time conceiving of itself primarily as a film company, took little initiative in engaging with, or even monitoring, the burgeoning radio market, save as a promotional tool for its films and stars. This explains the studio’s obliviousness to Hammett’s own licensing activities with respect to the character of Sam Spade. Chancing to hear a January 1948 episode of Suspense on CBS titled “The Kandy Tooth” that featured Spade, a Warner Bros. employee alerted the studio’s legal department, which, after reviewing its files and finding no license had been granted for this airing, directed the studio’s outside counsel, Gordon Files (of Freston & Files), to send letters alleging copyright infringement to the show’s producer, sponsor, and network. Not having yet done much research into the episode or the conditions of its production, Warner Bros. and their lawyers assumed that Sam Spade’s inclusion as a character meant that the radio show was an unauthorized adaptation of The Maltese Falcon.

Only after Files had sent the legal threats did Warner Bros. realize that the Suspense episode was not a stand-alone adaptation but rather a rebroadcast of two episodes of The Adventures of Sam Spade, a popular series produced by the Regis Radio Corporation, which, unbeknownst to Warner Bros., had been airing on CBS since 1946. Nor did the studio discover until months after it had filed suit in a California federal court against everyone involved in the radio show except Hammett that Hammett had formally licensed the character Spade to Regis in 1945 and had since then been receiving a $400 per episode royalty. Upon discovering this (as a result of a related legal action initiated by Hammett in New York), Warner Bros. amended its suit to include Hammett as a defendant. And so began what present-day legal treatises refer to as Warner Bros. Pictures v. Columbia Broadcasting System, or sometimes simply “the Sam Spade case.”

Unfortunately for Warner Bros., Hammett’s involvement transformed the studio’s relatively simple allegation that “The Kandy Tooth” had infringed their copyright in The Maltese Falcon into a major lawsuit that raised profound and consequential questions about the workings of U.S. copyright law. What Warner Bros. had initially perceived as a case of copyright infringement became, thanks to Hammett’s involvement, an almost metaphysical contest over the origin and scope of an author’s rights in the fictional characters he created. Although frequently misdescribed today as a technical dispute over the meaning of a contractual clause, Warner Bros. v. CBS was in reality a contest over the very essence of copyright—with “custom” (i.e., the accepted though usually unwritten practices of a distinct community) serving as the weapon by which it was fought.

That custom and its intersection with copyright came to play such an important role in the lawsuit was largely thanks to Hammett and his lawyer, Leonard Zissu. Both men, well versed in how the publishing industry worked, made custom the center of their defense. This surprised Warner Bros.’s legal team, which knew very little about publishing industry custom when they filed their suit. Only as the trial proceeded did they learn (partly through the work of the defendants and partly through their own research) how publishers traditionally handled rights in fictional characters.

Hammett argued in court that it had long been the practice of authors of detective fiction to reuse the detective characters they had introduced in one story in “later and different stories.” Such a practice, “as old as this form of literature itself,” was integral to how detective series fiction traditionally worked. The example he and his lawyer cited most frequently was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes—a character who appeared across 60 detective novels and short stories between 1887 and 1927—but more contemporary references were also made to S. S. Van Dine’s popular detective Philo Vance and Erle Stanley Gardner’s crime-sleuthing lawyer Perry Mason. Indeed, Hammett even pointed to his own work with Sam Spade: Between 1931 and 1932, he’d reused Spade for three short stories, originally published in magazines but a decade later collected in book form under the title The Adventures of Sam Spade and Other Stories. The “open and notorious custom” of reusing characters meant, Hammett argued, that in any business deal involving rights to an author’s work the default assumption was that the author would retain the right to reuse their characters in new stories. As he explained in a deposition:

In view of this known tendency it would be absurd to suppose that parties bargaining for anything like character, sequel, continuation or other similar rights would not make express provision therefor. And when it is further borne in mind that [Warner Bros.] . . . was a wide and experienced user and dealer in literary properties and prepared the very contract in suit the conclusion is utterly inescapable that no rights in connection with characters were being transferred apart from and beyond the use of characters in connection with the basic story told.

To support this argument, Hammett and Zissu employed two strategies. First, they used witnesses to describe for trial judge William Mathes how the publishing industry and detective genre worked. One of these witnesses was Hammett. Others included Howard Cady, senior editor at Doubleday, and William White (known professionally as Anthony Boucher), editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. The strategy worked, at least with Mathes, who began the trial skeptical that the practice of reusing characters was widespread enough to constitute a custom. Very quickly, however, the defense had changed his mind: “Having Mr. Hammett recall it to my mind, I should think it is a matter of common knowledge. Those [Van Dine and Gardner] are the most prominent writers in that field. It is a matter of common knowledge. I should think in their writings they reuse the characters, the main character.”

The second strategy Hammett and Zissu employed was to introduce a business deal between Warner Bros. and Hammett that suggested the studio itself understood and accepted this custom. In January 1931, Warner Bros. contracted with Hammett to write a new Sam Spade story, eventually titled On the Make. When Hammett delivered the finished story, Warner Bros.’s Darryl Zanuck rejected it, complaining in a letter to Hammett’s agent that “the finished story . . . has none of the qualifications of ‘Maltese Falcon,’ although the same character was in both stories.”

Why, Hammett asked, would Warner Bros. have needed to contract with him for a new Sam Spade story if they already owned the rights to the character? How much weight this argument was given by Judge Mathes or (later) the Ninth Circuit appellate judges is impossible to say, as neither mentioned the 1931 deal in their opinions. Still, it painted a picture of a plaintiff that had been, at best, inconsistent in its own interpretation of what rights it had acquired in The Maltese Falcon and thereby put Warner Bros. on the defensive.

Although Warner Bros.’s lawyers were able to muster a plausible defense for this second claim (by “the same character,” they argued, the studio had meant merely a private detective), when it came to the argument about custom they were in serious trouble. The problem, they came to understand, was that Hammett and his witnesses’ descriptions of publishing industry practice were correct. Indeed, even Knopf, which was not only the nominal copyright holder for the original Maltese Falcon but also (due to a quirk in legal procedure) Warner Bros.’s co-plaintiff, agreed with Hammett. “Exclusive publication rights,” explained Knopf’s lawyer in a 1951 letter to Files, “have not been regarded by the publishers as depriving the author from selling publication rights in sequels in which the same characters are used.” Knopf’s position, though never voiced in court, must have been devastating for Warner Bros.’s lawyers to learn as they struggled to craft a compelling case.

But the lawyers did not give up. Recognizing that they could not argue that the custom (of authors recycling characters) did not exist, they argued that the custom’s legal foundation had been incorrectly described by the defense. Their argument, clever but tortuous, was that because copyrights to mystery fiction such as The Maltese Falcon were in the 1920s and 1930s and sometimes still in the 1950s registered to the publisher, publishers were in these cases the sole owners of the copyright. It followed that when an author wrote a sequel, a publisher was, via an informal (often merely verbal) contract, granting the author the limited right to reuse one or more characters, which remained the property of the publisher. Warner Bros.’s other strategy was to argue that the publishing custom did not in any case apply to this particular dispute. What mattered here were the customs of the motion picture industry, which routinely bought rights to books so as to develop their various parts, including characters, for films in whichever way the studios saw fit.

As clever as these strategies might have seemed, both suffered serious weaknesses. First, and most obviously, no one in the publishing industry agreed with the studio’s characterization of how publishing custom worked legally. Indeed, the characterization appears to have been based upon a misunderstanding of what copyright registration in a publisher’s name meant. Unlike in the film industry, where copyright registration meant copyright ownership, in the publishing industry, the former was merely a convenient form of stewardship. The tradition of publishers registering copyrights in the books they published (a tradition already fading by the time the case was decided) had developed as an efficient solution to the problems posed by copyright formalities; it did not signify ownership of the underlying copyright. What is more, Warner Bros.’s account of the custom seemed to ignore a basic fact about author-publisher relations that was introduced at trial: Authors sometimes change publishers and nevertheless continue to publish books featuring characters they supposedly “sold” to their original publishers. Indeed, Hammett himself did this with Spade, publishing in book form a collection of short stories featuring the character with a publisher other than Knopf.

But that was not the only problem with the studio’s strategies, for they also seemed to reject the idea-expression dichotomy, a cornerstone of American copyright law for over a century, by positioning characters themselves—apart from the stories in which they featured—as protectable by copyright. Warner Bros.’s lawyers first advanced this argument in a brief for the Second Circuit Court of Appeals (in a related suit brought by Hammett), stating “that the copyright in every fictional and dramatic work embraces and protects at least two components, i.e., component plot and component characters; in short, that the copyright owner will be protected against the copying by others either of original plot or of original characters.” Neither Zissu nor the other defendants’ lawyers had any difficulty dismantling this argument. Characters, they countered, are not protected by copyright. Succinctly summarizing the case law, Zissu (writing with Abraham Marcus) explained:

Such text or expression as fully develops or delineates in detail a character by describing the character or his acts or setting forth his dialogue would be protected against copying as any other text or expression of a copyrighted work. Only that is meant, no more, in saying that a character may be protected under copyright when it is fully developed or delineated in detail.

Lest that suggest that characters are free for the taking by anyone who wishes to use them, the defense proposed that characters are protected as property by other kinds of law. In arguments that anticipated how IP law would evolve after 1978, they described character rights as “analogous to trade-mark rights” and contended that characters “would be protectible as a matter of common law under a doctrine of or akin to unfair competition.” By this argument, the defense was thus able to offer a simpler and more elegant legal basis for trade in characters that was also compatible with the idea-expression dichotomy.

Given the serious shortcomings in Warner Bros.’s arguments, one may wonder why the studio’s legal team made them in the first place and why they stuck with them so doggedly throughout the life of the dispute, all the way through to their petition to the U.S. Supreme Court for certiorari. First, it is worth remembering that a lawsuit is, among other things, a process of knowledge production and that the production of knowledge is not just for the purpose of educating the judge but also educating the parties themselves (or at least their lawyers). In this respect, Warner Bros. entered the dispute at a considerable disadvantage, for, in contrast to Hammett and Zissu, the studio’s lawyers knew very little about how the publishing industry (or even the radio industry) worked—to say nothing of the relevant facts regarding who had done what in what manner with respect to “The Kandy Tooth.”

To correct this imbalance, Warner Bros.’s legal team engaged in a tremendous amount of very rapid learning for themselves. Unfortunately, the development of their case could not wait until such learning was finished. The team was thus forced to develop, on the fly, avenues of argumentation based on hunches and analogical reasoning, most of which unfortunately proved to be dead ends. Although their lawyers endeavored to adapt, only so much course correction seems to have been possible once the first hearings had introduced the core facts and determined the basic framework for the dispute.

Except for a very early procedural win, Warner Bros. consistently lost its dispute with Hammett. The California district court found for Hammett and the other defendants, primarily along contractual lines, and the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Warner Bros.’s request for a hearing. But it was the Ninth Circuit appellate court opinion, authored by Judge Stephens, that represented Warner Bros.’s biggest loss and had the greatest implications for the development of intellectual property law in the United States.

Hammett, Judge Stephens concluded, did not convey the rights to his characters or the characters’ names in his contract with Warner Bros., nor had Warner Bros., “a large, experienced moving picture producer,” really “intended to take” them—for if it had, it would have named them in the contract.

“The conclusion that these rights are not within the granting instruments,” Stephens explained, “is strongly buttressed by the fact that historically and presently detective fiction writers have and do carry the leading characters with their names and individualisms from one story into succeeding stories”—a practice that Warner Bros. itself had not objected to when, “long after the Falcon agreements,” Hammett published additional stories featuring Spade.

Unlike Judge Mathes’s earlier opinion, however, Judge Stephens’s did not stop here; it proceeded to “consider whether it was ever intended by the copyright statute that characters with their names should be under its protection.” The answer was no. In a densely argued four paragraphs, the court explained its reasoning, which was premised, in a nutshell, on custom.

“The practice of writers to compose sequels to stories is old.” And although this practice is never mentioned by copyright statute, it would be unreasonable to assume that Congress had wished to restrict it. Were copyright understood to restrict such a practice, it would “effect the very opposite of the statute’s purpose which is to encourage the production of the arts.” When it comes to their creations, authors thus have a special right to reproduce in sequels characters from previous works, even when the rights to those works have been transferred to someone else.

These rights are not, however, completely unrestricted. An author cannot reproduce exactly the story of a work to which he has parted with the copyright. And it is at least possible to imagine a character being so integral to a story that the character could not in any fashion be reused without also reproducing that story—in which case the author would be barred by copyright from reusing the character. But those are the only restrictions. In Judge Stephens’s famous (or infamous) words, “It is conceivable that the character really constitutes the story being told, but if the character is only the chessman in the game of telling the story he is not within the area of protection afforded by the copyright.” Recognizing that in detective fiction, as in all iterative storytelling, the detective is such a chessman, the court thus concluded that the characters of The Maltese Falcon, foremost among them Sam Spade, “were vehicles for the story told, and the vehicles did not go with the sale of the story.”

This article is adapted, with permission, from Legal Stories: Narrative-based Property Development in the Modern Copyright Era (University of Michigan Press, 2024) by Gregory Steirer.

See Steirer, Gregory. Legal Stories: Narrative-Based Property Development In the Modern Copyright Era. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2024, ISBN 978-0-472-07682-6 (hardcover), ISBN 978-0-472-22171-4 (ebook) DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11537357.