At 10 a.m., Friday, February 21, 1930, St. Louis Metropolitan police swarmed Bayless Grove, a notorious dance hall and liquor resort in Affton, Missouri. While officers raided the house, others kicked in a cellar door, shouting, “Put ’em up!”

The police were looking for Jacob Hoffman, a bookmaker who had been kidnapped a few days earlier. They found him in the cellar, along with several of his kidnappers, members of the notorious Gas House Gang—so named because they met in the shadow of a huge gas tank—who were arrested, as were the owners of Bayless Grove.

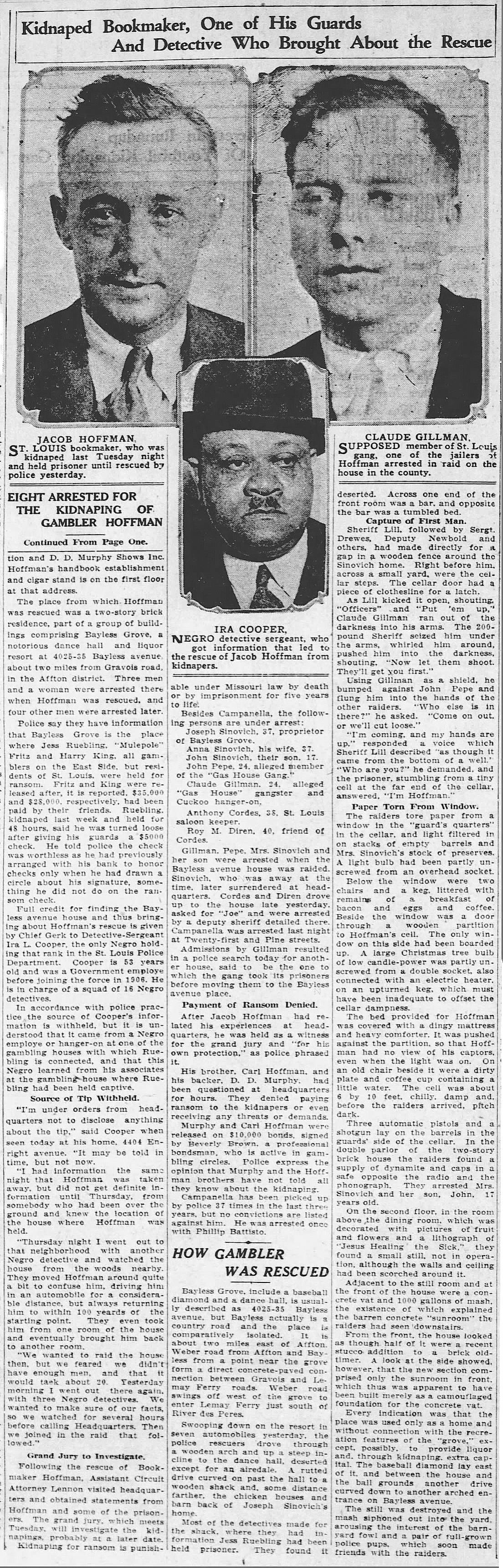

Among the cops making arrests that morning was African-American Detective-Sergeant Ira L. Cooper, who had located Hoffman from a tip.

“With two of my men, I went out Wednesday night and looked [Bayless Grove] over,” he said to a paper at the time. He saw a man being taken out of the house, driven around, and then brought back. He was sure it was Hoffman. “The first thing Friday morning, I went out and sized up the place by daylight to figure out how we could raid it without being seen first.”

Cooper, who was the first African American in the history of the force to hold the rank of sergeant and was in charge of a squad of 16 black detectives, told the officers the best route for the raid. For his valor, Cooper became the first African-American lieutenant. There wouldn’t be another on the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department until 1952.

“Ira Cooper was a very smart detective, and he was smart at a time that black people weren’t even considered first-class citizens,” says Gregory Carr, an instructor in speech and theater at Harris-Stowe State University. “But he achieved all of these amazing feats, despite social restrictions, which I think is more amazing than anything.”

Carr, an actor and playwright, recently presented a short one-person show about the detective as part of the Missouri Humanities Council’s Black History Month Series in February in conjunction with Harris-Stowe State University.

“There’s so much amazing history hidden in St. Louis,” says Carr. “Especially black history.”

Ira Cooper grew up in Mexico, Missouri, the son of schoolteachers. He attended college, earning a master’s degree at the Northern Illinois College of Optometry in Chicago. He moved to St. Louis and hung out a shingle.

“I soon discovered that a Negro eye doctor would starve to death—there wasn’t enough work to keep him busy,” Cooper said in an article in the Pittsburgh Courier in 1926. “So I looked for something better.”

He worked for the U.S. subtreasury as an assistant treasurer, and wrote for the St. Louis Palladium, an African-American Republican weekly. Later, he worked for the post office. Two friends said the police department was looking to hire blacks and he should apply. Cooper was earning $50 a month. As an officer he could earn $65, so he tested.

At the time, the city’s police regularly refused to hire qualified blacks, and from 1901 to 1921 black police officers who were hired were “Negro Specials,” only allowed to patrol black neighborhoods and do special duty. The police board determined the number of African Americans they wanted, hiring only that many, usually one or two. Black officers were ostracized, segregated, and rarely promoted.

Cooper was an exception. After being hired as a probationary policeman attached to the Detective Bureau, he became a plainclothes detective just a year later in 1907. Stout, slow-moving, and soft spoken, Cooper was, almost unexpectedly, one of the best cops on the force and called in to solve cases others could not crack.

He realized that train thefts totaling more than $40,000 were inside jobs; he solved the kidnapping case of Adolphus Busch Orthwein, grandson of August A. Busch, the beer baron of Anheuser-Busch brewery; and he located stolen jewels, earning a $3,000 reward, the largest ever given to a detective in St. Louis. He reportedly solved every case he was given.

“He was able to get information in a very quick manner and to act on it quickly,” says Carr. “He never let his leads go cold. His leads were always red hot. He solved one case in two hours for a Chinese diplomat.”

One of Cooper’s most famous cases was with Mercantile Trust Co. In just a few weeks, thanks to tips and keen observation, Cooper uncovered the perpetrators of an elaborate embezzlement scheme that had baffled bank officials and other detectives for years. For solving the case, Cooper became the fourth American ever to win an award from Britain’s Scotland Yard.

After cracking that case, Cooper turned his attention to an internal matter, the St. Louis Police Relief Association, which offered officers pensions and took care of their dependents when an officer was killed in the line of duty. Membership was open only to whites, but blacks petitioned to be admitted. In 1924, all of the blacks received applications, but they had to sign away their right to vote on association matters.

Cooper sent a letter to the association’s executive committee, writing, “I cannot stultify the pride and manhood I possess nor can I humiliate my family and my friends by signing an instrument which sacrifices every vestige of my manhood and makes me a cringing craven thing unworthy of contact with men.” He asked that they admit blacks as full members. And two months later, the association did.

In 1939, Cooper died of heart trouble. He was 61 years old. He’d left the force only three weeks earlier, due to illness.

When Carr started researching Cooper, he was surprised by the dearth of information. Cooper doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. Carr is working to get a street named after him and a statue put up, to help people remember the detective.

“His actions spoke,” says Carr. “They said, ‘I know that because I’m black, society believes I should be restricted, but I refuse to be. I refuse to let society dictate to me who I should be.’”