Frederick Douglass is best known as an autobiographer and lecturer. His first autobiography, the now canonical Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, appeared in 1845 when Douglass was working as a paid lecturer for the white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison himself published the autobiography, and it became a national and then international best-seller.

Seven years later, and just two years after Douglass had publicly broken with Garrison, Douglass delivered, in 1852, what would become his most famous oration, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”. In that lecture, Douglass attacked the hypocrisy of a nation that celebrated freedom while slavery remained the law of the land. As he proclaims at the end of the lecture: “Your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity, . . . your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery.”

Several months after delivering this lecture, Douglass began writing his only work of fiction, The Heroic Slave, which was inspired by the true story of the slave rebellion aboard the Creole. According to Douglass, Madison Washington, the leader of the rebellion, was a patriotic freedom fighter in the heroic tradition of the American revolutionaries. Douglass first published the novella in the 1853 Autographs for Freedom, a fund-raising volume of antislavery writings, and then reprinted it as a four-part serial in the March 1853 issues of his newspaper, Frederick Douglass’ Paper. The novella, one of the few works of fiction published by an African American prior to the Civil War, is increasingly being recognized as a major work in Douglass’s canon and as an impressive work of art. It also has much to teach us about Douglass’s changing views of the antislavery struggle.

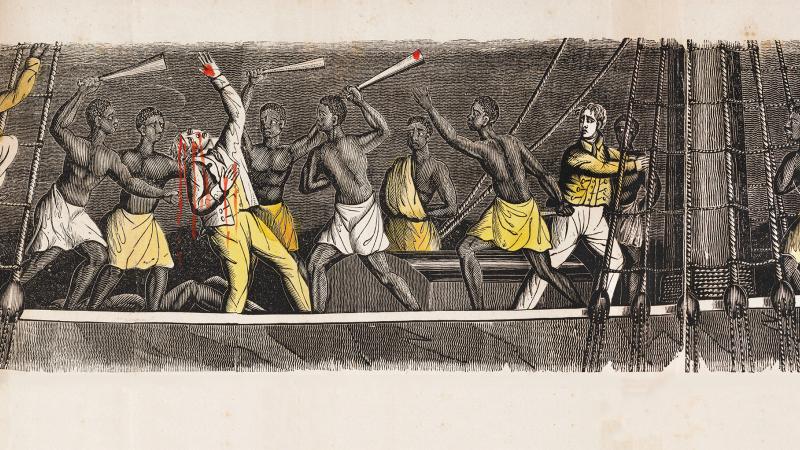

The rebellion on the Southern slave ship the Creole occurred in November 1841. Eighteen slaves, under the direction of Madison Washington, rose up against the white crew, killing an officer and then piloting the ship to Nassau in the British Bahamas. Much to the outrage of American authorities, the British immediately freed the more than 100 slaves not involved in the actual rebellion and eventually freed Washington and his fellow conspirators. Washington disappeared into history, but his legend as a successful leader of a slave rebellion continued to grow in black culture.

The same year that Washington led the rebellion, Douglass joined Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, but there is no record of his response to Washington until 1845, when, in a speech delivered at Cork, Ireland, he celebrated Washington for his “love of freedom.” Douglass continued to extol Washington in his speeches both in the United States and abroad, going so far as to proclaim, in a speech delivered in New York City in 1849, that he “would greet with joy the glad news . . . that an insurrection had broken out in the Southern States,” even as he warned Southerners “that there are some Madison Washingtons in this country.”

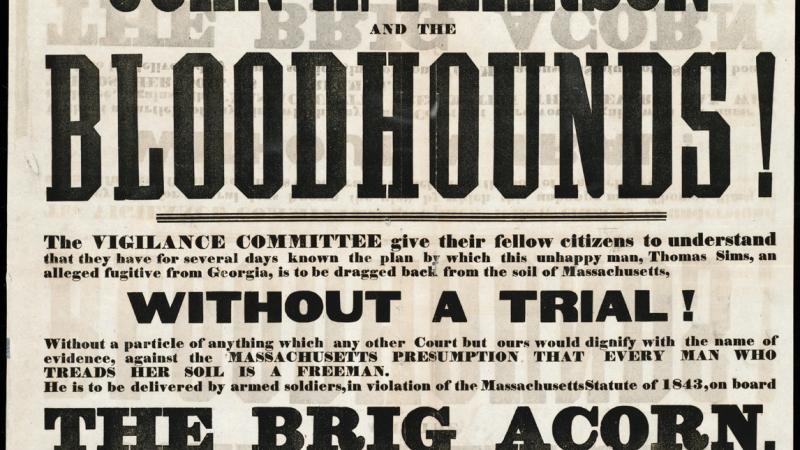

Douglass could not have written The Heroic Slave while a loyal member of Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, for Garrison argued first and foremost that antislavery should be a nonviolent reform. While working for Garrison, Douglass shared that view, and thus in one of the most famous scenes in his 1845 Narrative, Douglass portrays his rebellion against the slave-breaker Covey not as an aggressive act of violence but as a self-defensive wrestling match. But soon after the publication of the Narrative, Douglass began to dissent from Garrison on a number of issues, and in 1850 he publicly announced that he was no longer a Garrisonian. He rejected Garrison’s notion that the Constitution was a proslavery document, arguing that it was, in spirit at least, antislavery. As a result, Douglass began to promote involvement with the political process, while Garrison continued to shun electoral politics. Douglass also broke from Garrison on the matter of violence, asserting that slavery was an act of violence that should be met with violence. He underscored this position after the passage of the Compromise of 1850’s Fugitive Slave Act, which required Northern whites to return escaped slaves to their legal masters. Infuriated by this new development, Douglass called on antislavery people to physically resist the fugitive slave hunters.

As Douglass remarked in 1851 in a speech titled “Resistance to Blood-Houndism”: “I am a peace man. . . . But if any one should attempt to take me into Slavery, I should strike him down—not with malignity, but as complacently as I would a bloodhound, and think I was doing God service.” When James Batchelder of Boston was killed in 1854 while participating in the effort to remand the fugitive slave Anthony Burns back into slavery, Douglass applauded the act, stating that “his slaughter was as innocent, in the sight of God, as would be the slaughter of a ravenous wolf in the act of throttling an infant.” Given his new support for antislavery violence, it is not surprising that, when turning to fiction, Douglass would want to write about a slave rebel who used violence to liberate his fellow slaves.

Douglass published The Heroic Slave in 1853, less than a year after the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a work that sold over a million copies during the decade. While a number of African Americans objected to the novel’s racial stereotypes, and to an ending that seemed to suggest that blacks were better off “returning” to Africa, Douglass, a pragmatist, regularly praised the novel for the way it galvanized antislavery opinion in the North. One of the first notices of the novel appeared in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, with the reviewer proclaiming, “The friends of freedom owe the Authoress a large debt of gratitude for this essential service, rendered by her to the cause they love.”

In addition to being buoyed by the cultural work that the novel was doing, Douglass admired its interracial dimension, the way that it depicted whites sympathizing with the plight of the black slaves. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, sympathy leads to action, not in the form of violence but as charitable help, as a number of the white characters offer money and resources that allow fugitive slaves to make their way to Canada. Douglass brought that interracial dimension to The Heroic Slave, while raising questions about Stowe’s use of black stereotypes.

The Heroic Slave mixes fact and fiction. It provides a fabricated (fictionally imagined) prehistory of the Creole rebellion in which a white abolitionist has a significant role in enabling the freedom fighting of Madison Washington. That abolitionist, whose name is Listwell (throughout the novella he is a very good listener), is an invention that speaks to Douglass’s Stowe-like interest in white sympathy and also to his post-Garrison belief that antislavery action could include violent resistance.

The novella consists of four parts and has the feel of a stage play, in which the white abolitionist and black rebel have the central roles. In Part I, Listwell, while visiting a town in Virginia, overhears Washington lamenting his condition as a slave. Washington’s soliloquy is so powerful that at the end of the section Listwell declares: “From this hour I am an abolitionist.” Part II takes place five years later in Ohio. The now fugitive slave Madison Washington, by an astonishing coincidence, seeks refuge at what turns out to be the home of Mr. and Mrs. Listwell. While there, he tells Listwell about his escape from slavery, lamenting that he had to leave his wife and children behind in Virginia. At the end of the section, Listwell takes the man he now calls “friend” to a boat sailing for Canada. In Part III, Listwell journeys to Virginia on business, and, again by a theatrical coincidence, finds that Washington has returned for his family and been captured after failing to rescue them. Washington tells his story to Listwell while manacled to slaves who are about to be shipped to the New Orleans slave market on the slaver Creole. Part III ends with a dramatic moment. Listwell wants to help Washington, and initially offers him money. But, on second thought, he purchases three steel files that he smuggles to Washington. The files will soon allow Washington, when aboard the slave ship, to unshackle himself and his fellow coconspirators so that they can initiate their rebellion. The sympathetic Listwell, unlike a Garrison- or even Stowe-influenced abolitionist, is thereby implicated in black violence.

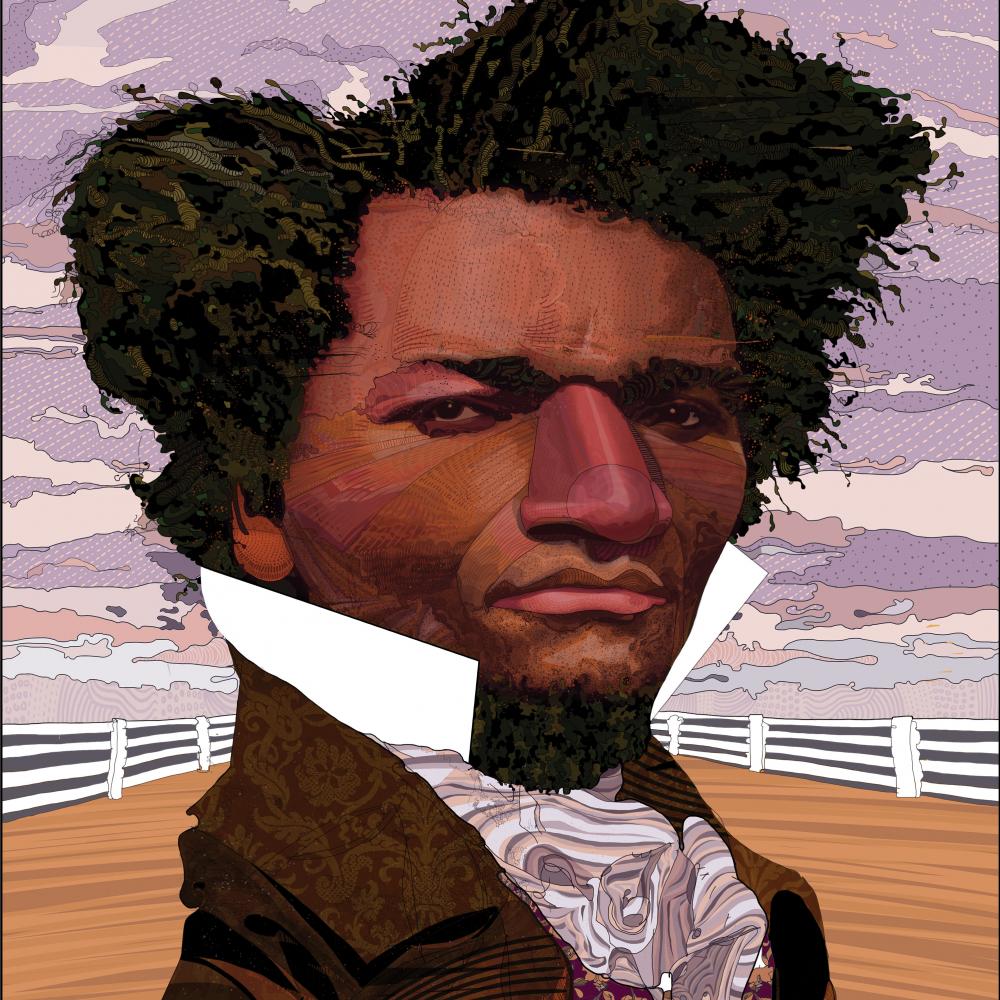

Douglass’s willingness to depict an interracial relationship that enables a slave revolt arguably serves his purpose in pointing to the limits of Garrison’s and Stowe’s nonviolent politics. Douglass also revises Stowe’s racial politics. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the only blacks willing to use violence are white to the eye. Uncle Tom himself, who is black-skinned, refuses to adopt violence, even when offered an axe that would help him liberate some of the slaves on the evil Simon Legree’s plantation. In the novel and elsewhere, Stowe evinces a racialist belief that blacks are more domestic and nonviolent than whites; it’s the supposedly aggressive “white” blood that makes a character like the white-to-the-eye slave George Harris willing to adopt violence in his effort to help his family escape from slavery. In The Heroic Slave, Douglass makes clear that Madison Washington, the man who chooses to lead a violent slave rebellion, is black to the eye. Drawing on the Song of Solomon, Douglass describes Washington in the novella’s first part as “black, but comely,” and he goes on to note that Washington “had the head to conceive, and the hand to execute.” Working against stereotypes found in Stowe and other writers of the period, Douglass creates a dark-skinned black character who is intelligent and, like the patriots celebrated during the Fourth of July, prepared to use violence in the service of freedom.

The novella culminates with the rebellion itself, and here, in its fourth and concluding part, Douglass draws on court transcripts and other documents about the rebellion to portray an exemplary instance of black revolutionary violence in American history. But he does so through an ingenious fictional invention: He has one of the Creole’s white officers, Tom Grant, tell the story of the rebellion after the fact to sailors at a Virginia coffeehouse. This narrative move allows Douglass to explore the psyche of the racist white enslaver, showing just how fragile his white supremacist and proslavery beliefs really are. Whether intended or not, the emphasis of Grant’s story is on the blacks’ humanity, exemplified by their decision not to wantonly kill the whites once they gain control of the ship.

Grant has so many good things to say about the intelligence and freedom-loving spirit of the black rebels that one of the sailors accuses him of being “as good an abolitionist as Garrison himself.” The outraged Grant vows that he’ll kill the next man who asserts such a thing, but then, seemingly unaware of the implications of what he is saying, he depicts Washington as a heroic slave. As he confides to his white companions: “I forgot his blackness in the dignity of his manner, and the eloquence of his speech.” Washington himself pushes Grant to view him in the heroic tradition of the American revolutionaries. As Washington declares to Grant, who then ventriloquizes the black rebel’s words to his coffeehouse companions: “You call me a black murderer. I am not a murderer. God is my witness that LIBERTY, not malice, is the motive for this night’s work. I have done no more to those dead men yonder, than they would have done to me in like circumstances. We have struck for our freedom, and if a true man’s heart be in you, you will honor us for the deed. We have done that which you applaud your fathers for doing, and if we are murderers, so were they.” The novella concludes with Grant describing Washington and his fellow rebels as they are hailed by the black soldiers of Nassau.

By the time Douglass wrote The Heroic Slave, he had come a long way from his commitment to Garrisonian nonviolence. He had also come a long way from his Garrisonian belief that antislavery people should avoid politics because of the proslavery nature of the Constitution. Douglass embraced politics with the hope that the nation could live up to the ideals of what he regarded as the antislavery spirit of the Constitution, eventually offering his support to the Republican party. And though he continued to celebrate black rebels like Madison Washington, he was a pragmatist when it came to violence. Thus, he decided not to participate in John Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry in 1859. But Washington remained one of Douglass’s heroes, and when the Civil War broke out and an African American named William Tillman used an axe to kill white Confederate soldiers at sea, Douglass, in an essay published in the August 1861 issue of Douglass’ Monthly, called Tillman “A Black Hero.” He then linked Tillman’s “love of liberty” to that which “had inspired . . . MADISON WASHINGTON” and other black rebels.

Over the next two years, Douglass worked strenuously and successfully to lobby Abraham Lincoln to allow African Americans to fight in the Union Army. There are many Douglasses, of course, including the “peace man” and the man who, after the Civil War, urged blacks to work hard at their trades and rise in the marketplace as self-made men. But the more radical side of Douglass, which is on full display in The Heroic Slave, remained important to his pursuit of black liberty during the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction decades. He spoke out vociferously against lynching, and near the end of his life developed close friendships with blacks in Haiti, whose own nation had been created, like the United States, through revolutionary violence. The Heroic Slave helps reveal a sometimes obscured and more radical aspect of Douglass’s antiracist politics.