On July 4, 1854, William Lloyd Garrison set fire to a copy of the U.S. Constitution. “A covenant with death,” he called it, “and an agreement with hell.” Holding the parchment above his head, he repeated forcefully a psalmic rouse to the hundreds of men and women gathered around him: “And let all the people say, Amen.” The crowd exploded: “Amen!”

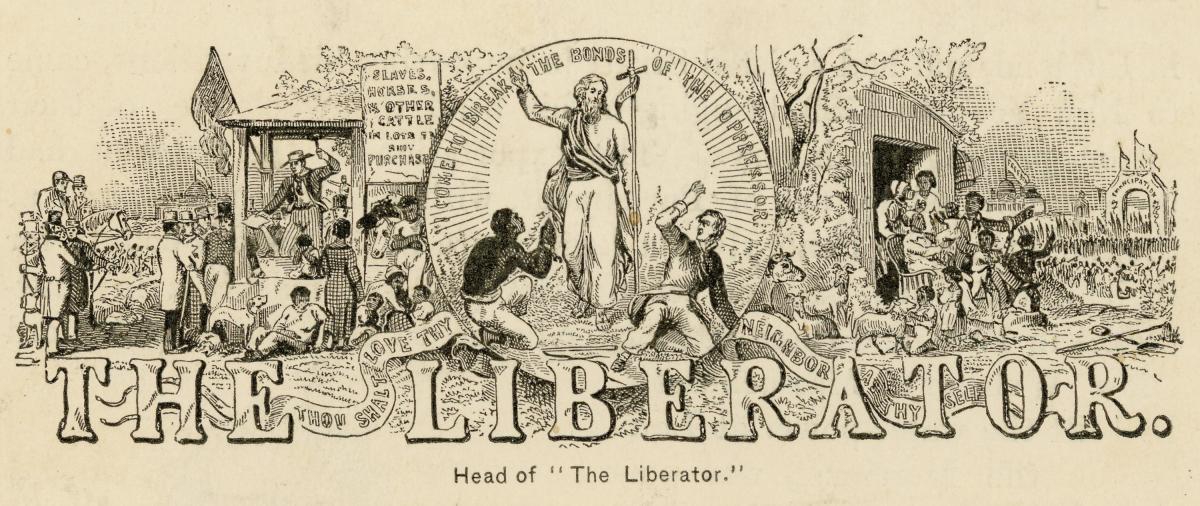

The climactic moment of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s Independence Day picnic—a somber affair held that year at Harmony Grove, just outside Boston—Garrison’s public immolation of the all-but-sacred law of the land dramatized an argument that he had been making in speeches and in the pages of his weekly newspaper, The Liberator, for a quarter century. The nation, he thought, was founded on an unsustainable contradiction: on one hand, the natural law of human liberty, as laid out in the Declaration of Independence; and on the other, the “peculiar institution” of the South, an evil expressly protected under the Constitution (in the three-fifths clause of Article I, for example, or the fugitive slave clause of Article IV). “It matters not what is the theory of the government,” he had written in 1845, “if the practice of the government be unjust and tyrannical.” And the practice of the present government, he continued, by pandering to the interests of slaveholders rather than upholding the principle of universal freedom, amounted to “a despotism incomparably more dreadful than that which induced the colonists to take up arms against the mother country.” There was more than a note of warning in Garrison’s allusion to the events of ’76: Only the immediate and absolute emancipation of the slave population could save the republic, he declared—anything short of that, any feeble compromise or token gesture of appeasement, and the North had a moral duty to secede. Later generations would learn about union and emancipation together, but in Garrison’s prewar reckoning, abolition could not be achieved without secession, without disunion.

“NO UNION WITH SLAVEHOLDERS” was by then Garrison’s all-cap motto. It was a heartfelt position, no doubt, but also designedly antagonistic—the kind of political expression meant to provoke reaction, one way or another. Perhaps, for Garrison, repealing the Union began as an empty threat, meant to raise awareness in the North and spur the South toward manumission. But slavery, his years of agitating had taught him, was thoroughly entrenched. To wipe the stain of complicity from the northern conscience, the Union had to be dissolved and the southern states left, without the military support of those in the North, to their fate. “So long as we continue one body,” he wrote, “a union—a nation—the compact involves us in the guilt and danger of slavery . . . What protects the south from instant destruction? Our physical force. Break the chain which binds her to the Union, and the scenes of St. Domingo would be witnessed throughout her borders.”

This was the crusading editor’s vision for the South: scenes like those of Saint-Dominque, the French colony that in the wake of a massive slave revolt that left thousands dead on each side had become the black-led nation of the Republic of Haiti. Such visions were in the air and, for southerners, almost tangibly threatening. In his famous 1829 Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, David Walker had described a similar day of judgment: an imminent uprising that would destroy the oppressors and free the oppressed from the “wretchedness and endless miseries . . . poured out upon our fathers, ourselves, and our children.” And, in 1831, Nat Turner had given the country an inkling of what that day might look like when, with a gang of other slaves and free blacks, he slaughtered fifty-five white Virginians—women and children among them.

Yet, for all his fire and foreboding speech, Garrison considered himself a pacifist, a believer in the power of truth to undo the wickedness of slavery without recourse to bloodshed. But were bloodshed to come, it would be nothing more than divine retribution for the blood of the slaves already spilt. Of the Nat Turner affair, he wrote: “I do not justify the slaves in their rebellion; yet I do not condemn them, and applaud similar conduct in white men.” Garrison could warn the country, but far be it from him to interfere with God’s vengeance, a gory “deluge from the gathering clouds,” he called it, if the country chose not to listen.

Garrison—complex, difficult, controversial—figures prominently among a group of antislavery activists, or agitators as they were then known, depicted in a new American Experience documentary called The Abolitionists. Covering more than four decades of the abolition movement, from the violent boyhood of escaped-slave-turned-celebrity Frederick Douglass through the conclusion of the Civil War, the film traces the intersecting lives and works of some of its most famous leaders: Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Brown, Angelina Grimké, and Theodore Weld. At its center, however, is Garrison—right where he belongs—the firebrand newspaperman whose passion helped draw more than a few of those leaders (and many others) to the cause, and whose increasing radicalism then gradually alienated them from his particular brand of emancipation politics.

A son of Massachusetts, the birthplace of American liberty, and heir to a tradition of moral reform that already included the First Great Awakening and the temperance movement, Garrison came to the role of hardline agitator honestly. He was born in 1805 in Newburyport and brought up by a mother who, as he later recalled, possessed a mind “clear, vigorous, creative, lustrous, and sanctified by an ever-glowing piety,” and by an elderly couple his mother knew from church, the Bartletts. As a young man—still a boy, really— he tried his hand at shoemaking, store clerking, and carpentry. None of it took. He learned to cobble what he called a “tolerable” shoe, but disliked clerking, and ran away from his carpentry apprenticeship after only a few weeks. Garrison could read, though, and when, in 1818, Uncle Bartlett saw a help-wanted sign at the Newburyport Herald, the twelve-year-old boy found himself conscripted to the newspaper business.

Garrison did the drudge work at first—the dull, noisome labor of sweeping floors, toting water, and stamping dry the urine- soaked sheepskins used to apply ink to the press. A quick study, he was soon sorting pied, or jumbled, type and setting columns for publication. He even found time to pen a few anonymous articles (signed “An Old Bachelor” or “A.O.B.”) that he slipped under the editor’s door at night. At the Herald, Garrison tested his voice, learned to lay out a page, and absorbed whatever wisdom he could glean from his master, Ephraim W. Allen, a man who believed that newspapers “ought to be made the vehicle, and a most effective one, too, for disseminating literary, moral, and religious instruction.”

That lesson and, as the scholars interviewed in The Abolitionists stress, the religious fervor of his mother would guide Garrison for the rest of his career: The news wasn’t an end unto itself, much less a moneymaking scheme in service to popular tastes, but a means of achieving some higher objective. For Garrison, however, just what that higher objective might be didn’t crystalize until 1828, when he encountered an itinerant Quaker abolitionist named Benjamin Lundy. Lundy was one of the few Americans—mostly Quakers—who had taken up and persisted in what many at the time considered the lost cause of emancipation. Lundy told Garrison of his own awakening to the evils of slavery (“the iron entered my soul,” he said), of his extensive travels since (he had preached abolition all over the country), and of his success in personally convincing slave owners to free their human property. Garrison was thrilled—his calling had come to him in the form of a slight, aged man with the kind of indefatigable moral convictions that made him seem immense. As Henry Mayer suggests in his biography, Garrison could see himself as Lundy a few years down the road. And the Quaker had a publication of his own, to boot: the Genius of Universal Emancipation, a Baltimore-based monthly dedicated to opening the eyes of the nation to its greatest sin.

For six months in 1829, Garrison took over editorial responsibilities at the Genius, reworking its look and radicalizing its message. He gave the paper a new emblem—an eagle—and went after any and all on the wrong side of his abolition program. Southern slave owners, especially those who defended slavery as an act of benevolence, were easy targets, and Garrison delighted in tearing their arguments apart. But his sights were set on the north, on mere complacency and the wrongheaded views of those who favored gradual emancipation or, worse, the resettlement of freed slaves at some overseas colony. Gradualism was kicking the can down the road—and if it could be kicked once, it could be kicked again and again. And the colonizationists, Garrison argued, were nothing but racists who couldn’t imagine an American society that would embrace blacks and whites. “My bible assures me,” he wrote, “that the day is coming when even the ‘wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid, and the wolf and the young lion and the fatling together’; if this be possible, I see no cause why those of the same species—God’s rational creatures—fellow countrymen, in truth, cannot dwell in harmony together.”

At the end of his tenure at the Genius (which was precipitated by a stint in a Baltimore jail for—the court claimed—slandering a merchant involved in the domestic slave trade), Garrison set out to start his own abolitionist paper, The Liberator. He tried first to set up shop in Washington, DC, but because he had tangled with the colonizationists, Garrison was shut out of business there.

Back he went to New England, where, Garrison said, he found “contempt more bitter, opposition more active, detraction more relentless, prejudice more stubborn, and apathy more frozen, than among slave owners themselves”—perfect territory, in other words, for an editor who worked best when embattled.

Using the tradition of newspaper exchange, by which editors sent complimentary copies of their latest numbers to each other, Garrison struck up debates, reprinted articles he liked, and added to those that he didn’t his own corrective commentary. His radicalism and provocative rhetoric (the best bits, like his “covenant with death” line, lifted directly from the Bible) made him enemies on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. Southerners, without much evidence, blamed The Liberator for Turner’s insurrection, and sent a steady stream of death threats and duel challenges to its editor. Northerners, some of them at least, thought Garrison “erratic and unbalanced” and encouraged him to shut down his paper altogether. Once, a proslavery mob in Boston tried to lynch him—a scene dramatically played in the film—and would have succeeded if it weren’t for a few burly sympathizers who turned him over to the authorities instead.

Garrison claimed abolition “common ground”—“upon which men of all creeds, complexions and parties, if they have true humanity in their hearts, may meet on amicable and equal terms to effect a common object”—but the ground he staked out for his cause was, as The Abolitionists suggests, also precipitously high. He eschewed political parties and religious organizations for fear that their interests would pollute those of the cause, and brooked no compromise when it came to matters of his moral principles or pacifism. There were tense (though friendly) letters of disagreement exchanged between Garrison and Stowe, who worried that the editor would “take from poor Uncle Tom his Bible, and give him nothing in its place.” And even Douglass, whom Garrison had discovered, so to speak, and worked with, criticized his former mentor’s lack of pragmatism, warning others against the tactics of abolitionists who wanted “rain without thunder and lightening . . . the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.” For Douglass, Garrison’s secession strategy was mere abandonment of the slaves, and his rejection of existing institutions, unnecessarily limiting. The struggle for freedom, he felt, required more than loud proclamations of absolute righ- teousness—it required the action of political parties and voters, the engagement of congregations, a revised understanding, not a rejection, of the U.S. Constitution, and, quite possibly, the use of force.

But “reform is commotion,” Garrison often said—his forte. And slavery, he had come to believe, would not be overthrown by moderation or half measures, but with “excitement, a most tremendous excitement.”

That tremendous excitement came, of course, in 1861, in the form of disunion and war. It didn’t happen the way that Garrison thought it might—the North didn’t secede from the South, and the slaves didn’t rise up en masse against their masters—but emancipation did finally seem possible. And Garrison, despite his pacifism (and initial distrust of Abraham Lincoln, whom he judged a waffler), announced himself “with the Government,” and then rejoiced in and even thanked God for the fratricidal conflict. “Never before,” he remarked just after the outbreak of hostilities, “has God vouchsafed to a Government the power to do such a work of philanthropy and justice.” The war, he hoped, referring to his earlier invocation of the nation’s infer- nal “covenant,” would “stop the further ravages of death and . . . extinguish the flames of hell forever.”