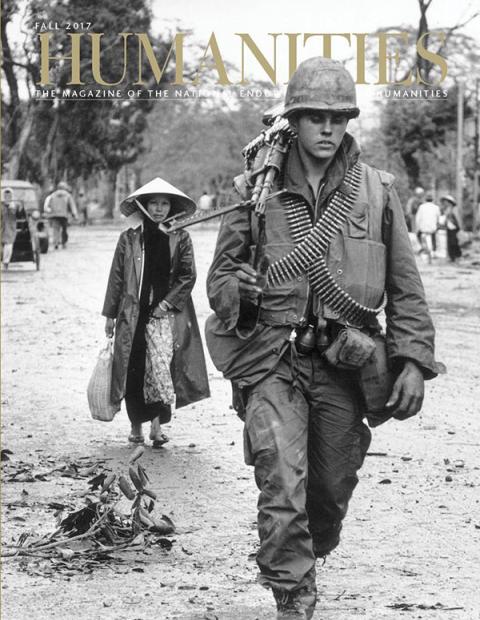

Two years ago, while visiting Walpole, New Hampshire, to supervise a Humanities interview with Ken Burns, I got to see a six-minute clip of The Vietnam War. Having spent the previous weeks watching Ken Burns films dating back to Brooklyn Bridge in 1982, I was startled by the new one.

The old black-and-white photos had given way to modern television footage. The music was not folksy or jazz; it was ’60s rock. The experience was immersive, and the action at times violent.

Some of that familiar haunting tone was still there, but it arrived alongside something else: a difficult awareness that the doubts and the horrors of Vietnam are still with us. The person on screen was not a historian talking about someone who’s been safely dead for a hundred years. No, I was listening to living witnesses talk about their own lives.

This was especially interesting to me. Over the years, films by Ken Burns and his team showed, I thought, an increasingly supple touch with interviewees, and not just the professional storytellers like Shelby Foote and David McCullough. Everyone on screen seemed more at ease, and with each new film the authentic voice of experience became more audible.

So when I heard that Lynn Novick, codirector on several of Ken Burns’s films, was talking publicly about how their team approaches interviews, I knew we had to interview the interviewer. Novick said we should also talk to producer Sarah Botstein, so Meredith Hindley interviewed them both.

As we reconsider the Vietnam War, it pays to know how the scholarship has changed. Mark Atwood Lawrence of the University of Texas at Austin, author of two books about Vietnam, describes the paradigm shift that has taken place in his field as a result of new access to archives here and overseas and the improving language skills of the war’s historians.

An essay in this issue by Professor David Haven Blake tells the story of a course he taught on the history of fame, revealing not only what his millennial students learned about Saint Augustine but also what Saint Augustine may have understood about millennials. Writer Bruce Falconer takes an inward turn to discuss the classic American story collection Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson, and Emrys Westacott steps back from the current vogue for minimalism to describe how a handful of philosophers since Aristotle have argued against frugality. More is more, they said.

With this issue we congratulate Jon Parrish Peede, who has been acting chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities since late July. Peede worked for several years at the National Endowment for the Arts as a director of literature grants and as a counselor to former Chairman Dana Gioia and was, before coming to NEH, publisher of the Virginia Quarterly Review. You can find his full bio at neh.gov.