Earlier this year, when the New York Times asked novelist and essayist Roger Rosenblatt to name the best memoir he’d read recently, he was unequivocal in his reply. “Speak, Memory, recently or ever,” Rosenblatt told the Times.

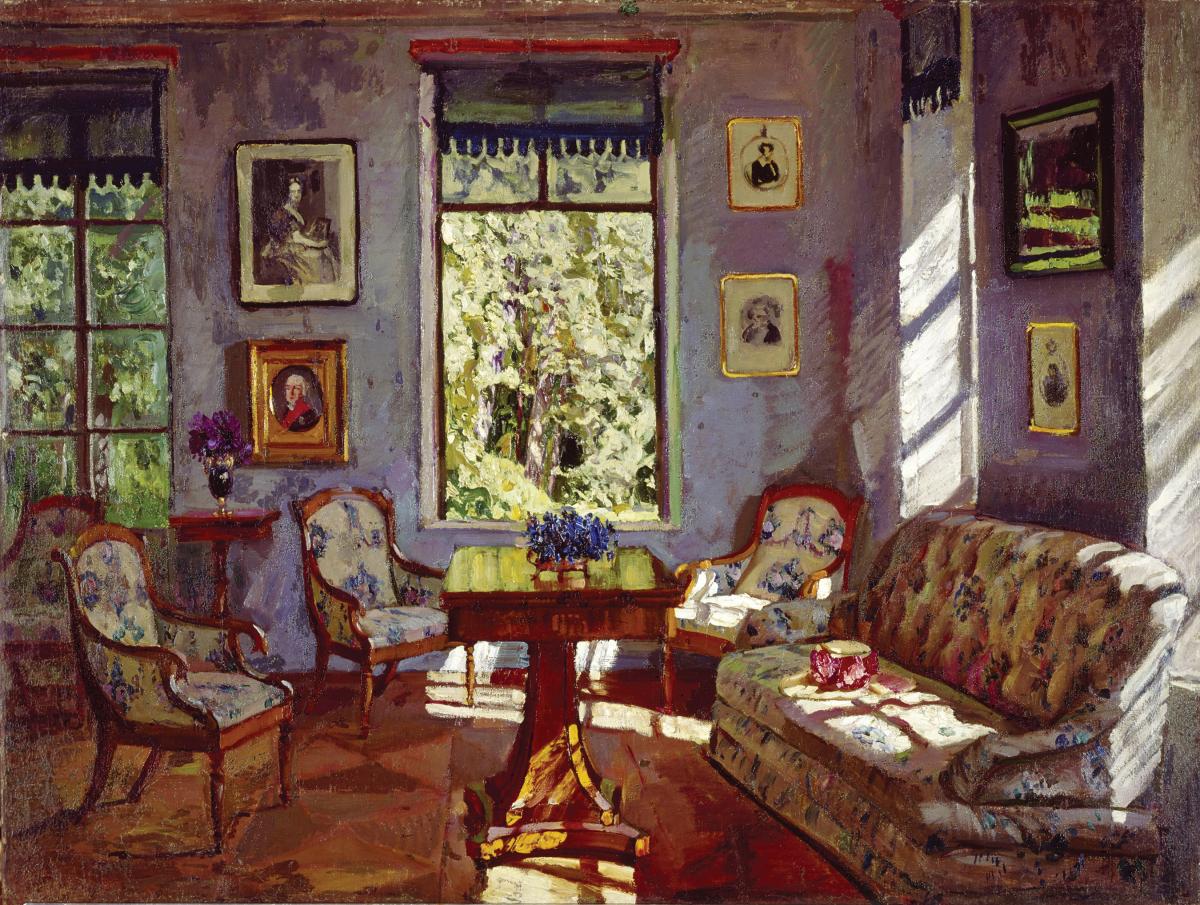

He was referring to the classic account by Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) of his idyllic Russian childhood in a family of colorful aristocrats, the 1917 Bolshevik revolution that banished him to exile, and the path that would eventually lead him to live in the United States.

Rosenblatt is far from alone in hailing Speak, Memory as a gem. “To write superior autobiography one requires not only literary gifts, which are obtainable with effort, but an intrinsically interesting life, which is less frequently available,” literary critic Joseph Epstein once observed. “Those who possess the one are frequently devoid of the other, and vice versa. Only a fortunate few are able to reimagine their lives, to find themes and patterns that explain a life, in the way successful autobiography requires. Vladimir Nabokov was among them.” After closing the pages of Speak, Memory, John Updike, no slouch himself as a prose stylist, was carried away. “Nabokov has never written English better than in these reminiscences; never has he written so sweetly,” he declared. “With tender precision and copious wit . . . inspired by an atheist’s faith in the magic of simile and the sacredness of lost time, Nabokov makes of his past a brilliant icon—bejewelled, perspectiveless, untouchable.”

Updike was writing in 1966, the year that the definitive version of Speak, Memory, subtitled An Autobiography Revisited, was published. That edition is 50 years old this year, still in print after half a century, and still attracting new readers. Perhaps no one would be more surprised at the book’s longevity than Nabokov himself. He pronounced the memoir “a dismal flop” after its release, lamenting that it brought him “fame but little money.”

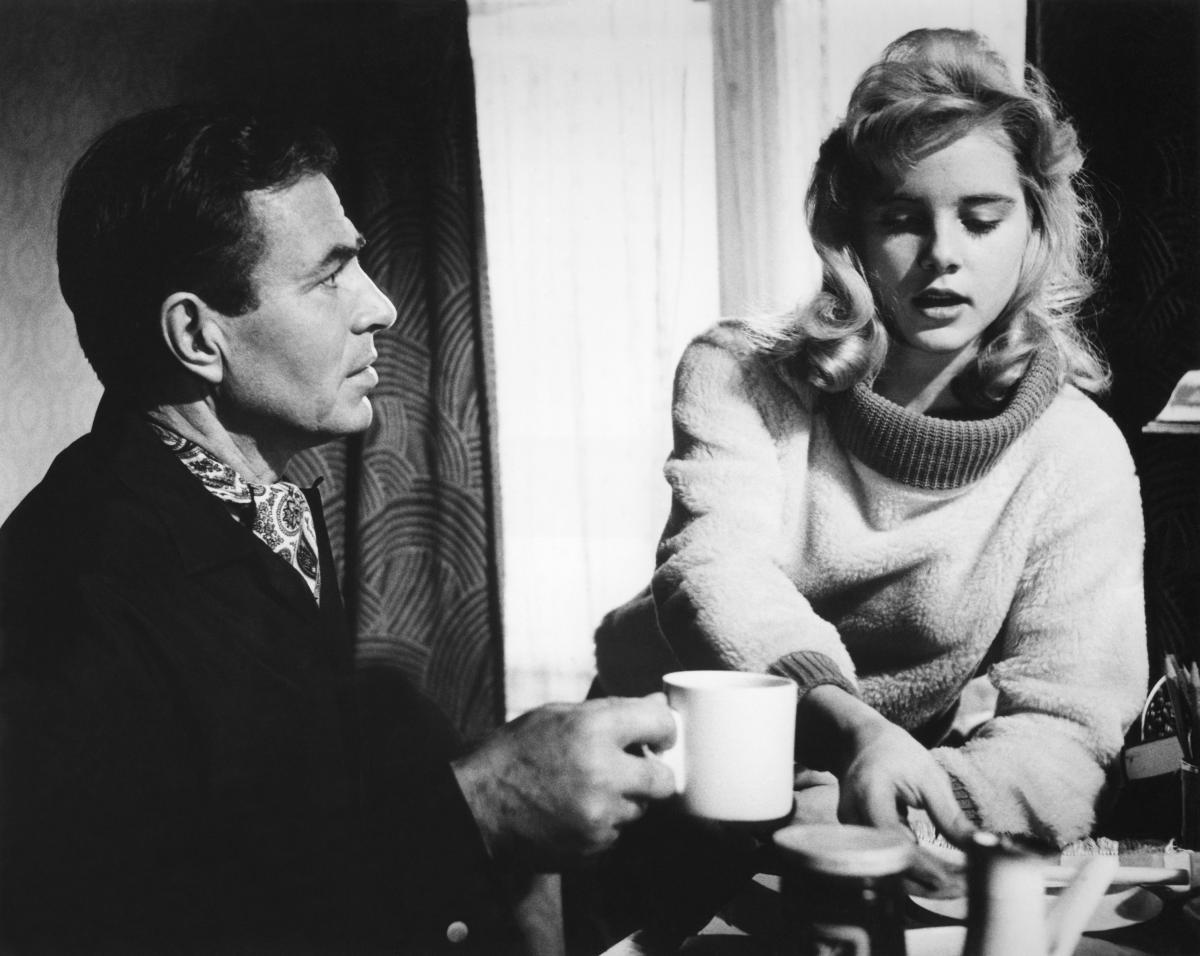

The work that had made Nabokov a lucrative author and ensured his financial security was—you guessed it—his controversial novel Lolita, which became an international sensation in 1955 with its tale of a shrewd pedophile’s relationship with his 12-year-old stepdaughter.

Lolita looms so large over Nabokov’s literary legacy that the more quietly observed Speak, Memory is destined to lie in its shadow. But if Nabokov had never written Lolita —indeed, if he had never written the novels Mary, or Pnin, or The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, or Pale Fire, or any of the poems or works of criticism that won him an international audience—then he would still deserve to be remembered for Speak, Memory, his exquisite paean to memory itself.

The sly illusion in Nabokov’s memoir resides in the very title, Speak, Memory, which evokes the idea of an earnest scribe waiting for the mythical Greek goddess Mnemosyne to talk so that he can scrupulously transcribe the past. But Speak, Memory, we learn in Nabokov’s foreword, wasn’t the book’s first name. His memoir was initially published in 1951 as Conclusive Evidence, though that choice proved problematic. “Unfortunately, the phrase suggested a mystery story,” Nabokov explained, “and I planned to entitle the British edition Speak, Mnemosyne but was told that ‘little old ladies would not want to ask for a book whose name they could not pronounce’ . . . so finally we settled for Speak, Memory.”

Yet the declarative certainty within the premise—Mnemosyne as an infallible arbiter of one’s personal history—is quickly betrayed by the interior logic of the narrative. Nabokov’s 1966 version of the book, we learn, was intended as a corrective to the earlier work, a revision meant to clean up flawed recollections in the first edition. “I revised many passages and tried to do something about the amnesic defects of the original—blank spots, blurry areas, domains of dimness,” he reports. “I discovered that sometimes, by means of intense concentration, the neutral smudge might be forced to come into beautiful focus so that the sudden view could be identified, and the anonymous servant named.”

Some of Nabokov’s revisions occurred after he returned to Europe following a 20-year absence, connecting with relatives who helped him realize that “I had erred, or had not examined deeply enough an obscure but fathomable recollection.”

Therein lies the central tension of Speak, Memory. Its prose is meticulous, suggesting memory as an exercise in exacting dictation from an omniscient oracle, yet its message points to memory as mutable, prone to the passage of time and the vagaries of imagination. “Fairly early in the book Nabokov spends pages and pages creating an exquisite picture of the vast figure of Mademoiselle, his childhood nanny, everything detailed, from her voice to her chins,” Rosenblatt notes. “Then he reverses course and says: Did I get her all wrong? Is she a fiction? Who but Nabokov could get away with a stunt like that—to make us believe all he has written about the woman, and doubt every word, and not care.”

This delicious ambiguity starts right away, in Nabokov’s reference to his birth, which was April 10, 1899, according to the Old Style calendar, largely derived from the Julian calendar, used in Russia at the time. It was generally 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar in widespread use outside Russia, which would make Nabokov’s birthday April 22 once he left his homeland. But “with diminishing pomp, in the twentieth century, everybody, including myself, upon being shifted by revolution and expatriation from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian, used to add thirteen, instead of twelve days to the tenth of April,” he confesses.

It’s a seemingly small point, yet a profound one. Without self-pity or bitterness, Nabokov reveals how exile can disrupt the underlying realities of personal identity—even something as basic as one’s birthday.

The theme of dislocation subtly informs the rest of Speak, Memory. In a particularly lovely passage, Nabokov fondly recalls his mother’s return from hunting mushrooms, when she would lay out her trophies on a garden table to sort them:

As often happened at the end of a rainy day, the sun might cast a lurid gleam just before setting, and there, on the damp round table, her mushrooms would lie, very colorful, some bearing traces of extraneous vegetation—a grass blade sticking to a viscid fawn cap, or moss still clothing the bulbous base of a dark-stippled stem. And a tiny looper caterpillar would be there, too, measuring, like a child’s finger and thumb, the rim of the table, and every now and then stretching upward to grope, in vain, for the shrub from which it had been dislodged.

This is vintage Nabokov: everything bright and beautiful, then the sudden lurch of disruption—in this instance, as an innocent creature struggles valiantly to reclaim the familiar home from which it’s been so casually uprooted, inviting an obvious comparison to Nabokov’s own exile.

Born at the dawn of the twentieth century, Nabokov encountered a life that seemed destined to register, as vividly as a seismograph, the titanic political and social upheavals of his age.

After Vladimir Lenin came to power in Russia, Nabokov’s family escaped to Europe in 1919. In subsequent years, Nabokov would study at Cambridge and live in Berlin and Paris. He met his wife, Vera, a fellow Russian émigré, during his Berlin period, and a shared love of literature grounded their relationship. Their son, Dmitri, was born in 1934. Nabokov struggled to support himself as a writer, and his life became more complicated when the family’s presence in France coincided with the Nazi advance. They fled to America in 1940, just in time to escape danger.

“The Nabokovs had been through the historical wringer,” biographer Robert Roper noted in his recent book, Nabokov in America:

They were Zelig-like figures of twentieth-century catastrophe, dispossessed of their native Russia by the Bolsheviks, hair’s-breadth escapees of the Nazis in Berlin and Paris, ”little” people with a monstrous evil breathing down their necks. Had they been in Russia that summer of ’43, they might have been among the thousands starving to death during the Siege of Leningrad, the most murderous blockade in world history; had they been in France, which they’d escaped at the last moment, on the last French ship for New York, Vera, who was Jewish, and their young son would likely have been destined for Drancy, the French internment camp that fed Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In America, Nabokov briefly taught literature at Wellesley, then secured a more permanent post at Cornell. He seemed to love his newfound country. “His embrace of it,” writes Roper, “and his comfort with the changes it forced on him had something to do . . . with being able to raise a healthy, promising child in America at midcentury.”

Even so, Nabokov avoided putting down roots outside his homeland. “Nabokov was never at home, literally or figuratively, after his departure from Russia in 1919,” writes critic Peter Quennel. “Never again would he own a residence. With Beckett he was our laureate of the lonely room, the saddest of digs.”

Maybe so, but there’s joy and humor and expectancy in Nabokov, too, as fabled New Yorker editor Harold Ross surely recognized when he published the vignettes that would become the basis for much of Speak, Memory.

The book’s origin within periodical journalism accounts for its episodic quality, a convenient analog for the fragmentary way in which memory actually works. Instead of following a strictly chronological line, the memoir unfolds like the images of a lantern slide, with poetical portraits of Nabokov’s mother, father, uncle, teachers, and other figures from his childhood.

It’s a deeply visual work, so much so that Updike found the use of family photographs to illustrate Speak, Memory a little beside the point. The photos, he groused, “make the book more of a family album and slightly less of a miracle of impressionistic recall.”

Chapter Six opens with a typically evocative word picture:

On a summer morning, in the legendary Russia of my boyhood, my first glance upon wakening was for the chink between the white inner shutters. If it disclosed a watery pallor, one had better not open them at all, and so be spared the sight of a sullen day sitting for its picture in a puddle. How resentfully one would deduce, from a line of dull light, the leaden sky, the sodden sand, the gruel-like mess of broken brown blossoms under the lilacs—and that flat, fallow leaf (the first casualty of the season) pasted upon a wet garden bench!

But if the chink was a long glint of dewy brilliancy, then I made haste to have the window yield its treasure. With one blow, the room would be cleft into light and shade.

Clearly, Nabokov wrote for the eye, which isn’t surprising for a man who claimed to hear language as a form of color. The long a of English “has for me the tint of weathered wood,” he mentioned by way of example. “I see q as browner than k,” he added, “while s is not the light blue of c, but a curious mixture of azure and mother-of-pearl.”

Nabokov’s pairing of sound and color, a mixing of the senses known as synesthesia, recalls Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, in which the taste of a madeleine cookie prompts an involuntary flood of childhood memories. Like Proust, Nabokov sometimes celebrates memory as a spiritual epiphany, the past prompting personal revelation through the magical alchemy that renders experience into literature.

“Nabokov once said that he was ‘born a painter,’” scholars Stephen H. Blackwell and Kurt Johnson point out, also noting that as a boy Nabokov took drawing lessons from the celebrated artist Mstislav Dobuzhinsky.

The late Alfred Appel Jr., a prominent Nabokov expert and his former student, recalled that Nabokov would sometimes teach in pictures at Cornell. One sleepy May afternoon during a class in European literature, Nabokov thought he heard a cicada, then proceeded to diagram the insect on the chalkboard, detailing how it created its wondrous sound.

“As a writer, I am half-painter, half-naturalist,” Nabokov told Appel in 1966. Nabokov’s naturalist streak expressed itself primarily in his passion for butterflies. They appealed to his keen grasp of visual beauty, and their fragile existence affirmed his sense of life as deeply transitory. He explains his avocation in Speak, Memory:

I have hunted butterflies in various climes and disguises: as a pretty boy in knickerbockers and sailor cap; as a lanky cosmopolitan expatriate in flannel bags and beret, as a fat hatless old man in shorts . . . Few things indeed have I known in the way of emotion or appetite, ambition or achievement, that could surpass in richness and strength the excitement of entomological exploration.

After moving to America in the 1940s, Nabokov delighted in new opportunities to catch butterflies. “In his forties Nabokov was still stubbornly youthful,” writes Roper. “Despite the dentures and the tubercular look, he was physically vigorous, youthful also in the sense of being deeply enamored of himself. . . . During his twenty years in America, he traveled upward of 200,000 miles by car, much of it in the high-mountain West, on vacations organized around insect collecting.”

In a new book, Fine Lines, Blackwell and Johnson argue that Nabokov was more than a mere amateur lepidopterist, his drawings and insights making a real contribution to understanding evolutionary biology. “I cannot separate the aesthetic pleasure of seeing a butterfly and the scientific pleasure of knowing what it is,” Nabokov said.

On his road trips through America, Nabokov gained a familiarity with the landscape that would inform Lolita, his signature novel. Decades after its publication, Lolita’s subject matter continues to shock, and its most disturbing aspect lies in its basic contradiction: How could something so beautifully written advance a story of such utter debasement? Here again, Nabokov’s enduring fascination with memory figures into his art. The novel’s central character, Humbert Humbert, tells the story in retrospect, giving a morally bankrupt relationship the grandness of myth. Lolita is about many things, but one of its themes is the plasticity of the perceived past—how it can be bent through the biases of recollection to serve our personal conceits. In a kind of counterpoint to Speak, Memory’s treatment of the past as pure transcendence when transmuted into narrative, Lolita hints at literary recollection as a corrupting influence as dark as Humbert’s carnal appetites. That Humbert is a supremely sophisticated aesthete suggests the book as a cautionary tale about the black magic of art, its power to not only define reality but distort it.

But in Speak, Memory, Nabokov implies that memory, flawed though it may be, is the closest thing we have to a fixed star in a rootless world. He speculates that, when it came to remembering things, “Russian children of my generation passed through a period of genius, as if destiny were loyally trying what it could for them by giving them more than their share, in view of the cataclysm that was to remove completely the world they had known.”

Nabokov colonized the English language so deftly in his prose that it’s easy to forget his Russian origins. His family, ardent Anglophiles, immersed him in English at an early age. In fact, his father was dismayed to learn that the young Nabokov could read and write English but not Russian, sending for the village schoolmaster to address the imbalance.

He seemed a citizen of the world, spending his final years in Switzerland before passing away at age 78 in 1977.

Five decades after its arrival, Speak, Memory still reminds readers that we’re really all wanderers, here for just a short while. “The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness,” Nabokov wrote. “That this darkness is caused merely by the walls of time separating me and my bruised fists from the free world of timelessness is something I share with the most gaudily painted savage.”