Thanks to the popular 1994 movie Four Weddings and a Funeral, thousands of people who had probably never read a word from poet W. H. Auden have been exposed to his work. In one scene, a character eulogizes his companion by reciting Auden’s “Funeral Blues” for the other mourners.

The poem is also known as “Stop all the clocks,” a reference to its rousing first stanza:

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Each of the four stanzas reads like an eloquent study in grief, including the last four lines, which leave a lump in the throat:

The stars are not wanted now: put out every one;

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun;

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

Auden’s poem resonates with readers because it addresses a basic emotional predicament—that after someone dies, the world keeps spinning without them. It’s an alternately affirming and cruel reality, a puzzle that the poem’s narrator, like many who have lost a loved one, seems to feel is not quite right. If a precious life has ceased, the anguished voice at the heart of “Funeral Blues” argues, then everything else should end, too.

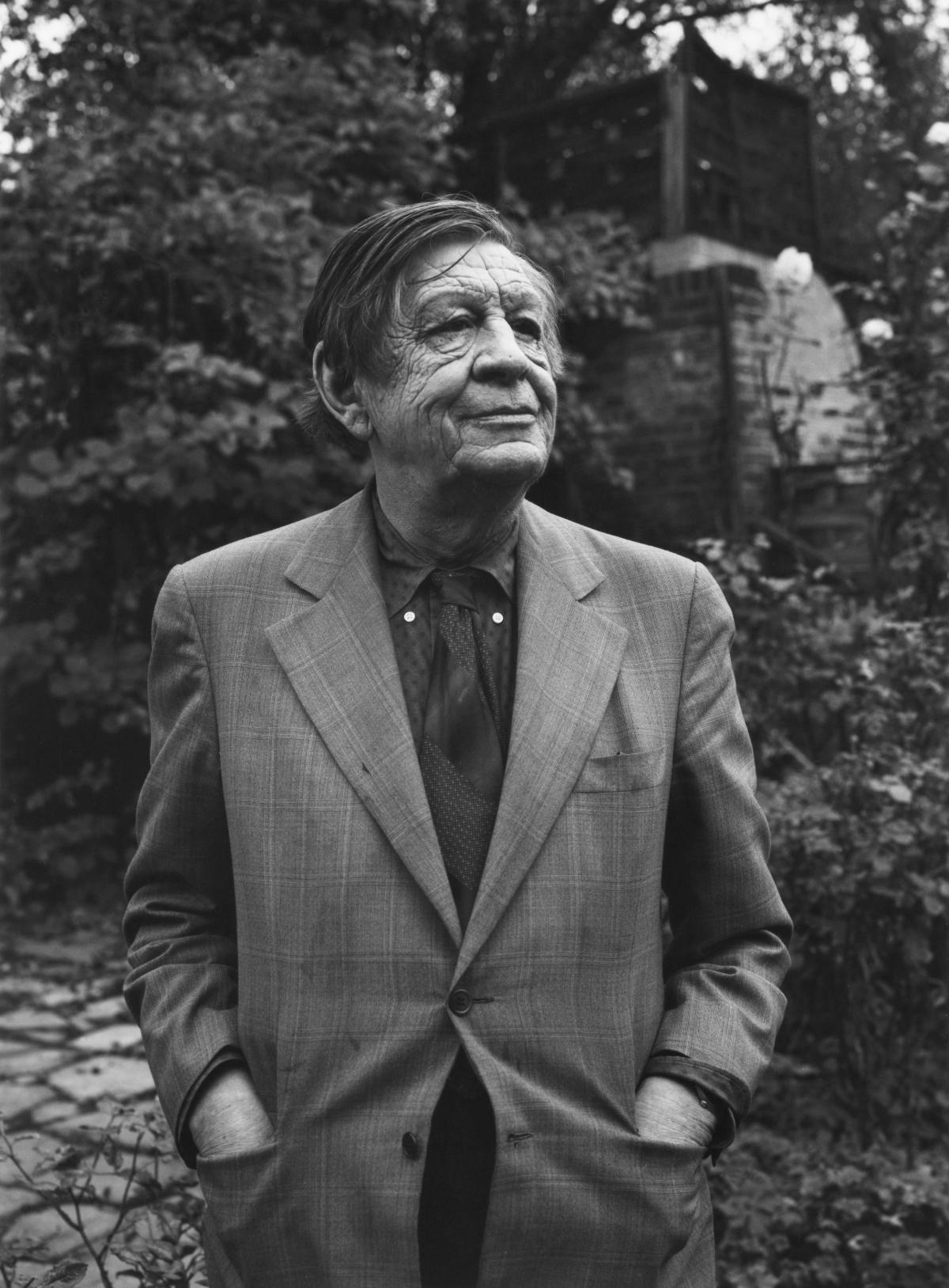

Auden, the celebrated British-born bard who died in 1973 at 66, explored the interplay between death and the larger pattern of existence in other poems. In his widely anthologized “Musée des Beaux Arts,” Auden contemplated how people could endure crisis while their fellow humans went about their business:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking

dully along;

In the final stanza, the narrator views a masterpiece painting inspired by the legend of Icarus, who perished when the sun melted his wings of wax and feathers. He ponders the picture as a window into the absurdity of life’s prosaic routines, even in the midst of tragedy:

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get and sailed calmly on.

The universe seems more consonant, however, with the death of a great figure in “In Memory of W. B. Yeats,” which also ranks among Auden’s signature works. Written to mark the passing of a writer who had deeply influenced Auden, the poem suggests that Yeats’s earthly end chills the world as well:

He disappeared in the dead of winter:

The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted,

And snow disfigured the public statues;

The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day.

What instruments we have agree

The day of his death was a dark cold day.

The rest of Auden’s poem is just as lovely as its first stanza, although “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” takes some creative license. “Actually, the weather was pretty good in France when Yeats died there,” writer Robert Alden Rubin has pointed out. Maybe the weather was bleak from Auden’s window as he wrote in honor of Yeats, or perhaps the point, as Auden sees it, is that the sky should have been dark as a great poet passed away. The ominous cold of “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” parallels a profound historical coincidence that Auden addresses later in the poem. Yeats died in 1939, the same year as the start of World War II. Auden hints that in the face of oncoming tyranny, a poet like Yeats can affirm the basic dignity of the individual soul:

With the farming of a verse

Make a vineyard of the curse,

Sing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress;

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.

Although Auden’s poetry often registers the apparent indifference of the cosmos to the trials of mortality, his poems also affirm the power of art to transcend the grave. “Musée des Beaux Arts,” for example, contains a subtle paradox. Its narrator is inspired to muse on the fleeting fortunes of Icarus after viewing an old painting. The durability of the picture itself suggests, however, that its creator—who might not be the sixteenth-century artist Pieter Bruegel, according to recent research—has cheated death by making a masterpiece that speaks across centuries.

Similarly, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats,” while ostensibly closing the coffin lid on a great writer, affirms Yeats’s continuing presence in the life of the culture: “You were silly like us; your gift survived it all: / The parish of rich women, physical decay, / Yourself. . . .”

That theme naturally invites the question of Auden’s own staying power. Some 45 years after his death, does his legacy endure? When his heart gave out on September 29, 1973, in Austria, it wasn’t entirely clear that Auden’s fame would survive him. “The day after W. H. Auden’s unexpected and untimely death, I was incensed to see a suggestion in the New York Times to the effect that the poet’s work might not outlive him,” the American poet L. E. Sissman lamented at the time. In making the case for Auden’s continuing relevance, Sissman argued that, among other things, he was “a virtuoso poet, capable of besieging and capturing the most difficult of traditional forms, from the sestina and the villanelle to the canzone; capable in almost the same breath of mimicking the tempo and language of an American blues or folk song; capable of a Popean delicacy of means or a Swiftian volley of scorn; capable of Anglo-Saxon sparseness and Tennysonian orotundity.”

He was able to inhabit the idioms of many places in large measure because he was, at heart, a citizen of the world. Born and raised in England, he traveled widely, including visits to Iceland, Germany, and China. He spent some of his most productive years in America, after he moved there in 1939, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1946. “From 1948 to 1972,” notes Edward Mendelson, an Auden scholar and the poet’s literary executor, “he spent his winters in America and his summers in Europe, first in Ischia, then, from 1958, in a house he owned in Kitchstetten, Austria.”

His childhood nurtured his curiosity. Wystan Hugh Auden was born on February 21, 1907, in York, “the third son of highly educated upper-middle-class parents,” Mendelson writes. “His father, who was expert in archaeology and languages, was a physician who became a professor of public health. His mother trained as a missionary nurse after taking an honors degree in French. One of Auden’s older brothers became an accomplished geologist and, later, an official in the World Health Organization.”

“He had hazel eyes, and hair and eyebrows so fair that they looked bleached,” says biographer Humphrey Carpenter. “His skin, too, was very pale, almost white. His face was marked by one small peculiarity, a brown mole on the right cheek. He had big chubby hands, and soon developed flat feet. He was physically clumsy, and took to biting his nails.”

As a boy, Auden considered becoming a mining engineer. When he was thirteen and away at boarding school, however, a classmate asked him if he wrote poems. Mystery novelist Alexander McCall Smith, a huge Auden fan, sees that exchange between Auden and his friend as truly historic. “This may reasonably be seen,” Smith tells readers, “as one of the great, crucial moments in the arts, akin, perhaps, to the moment when it was suggested to Shakespeare—as it might well have been—that he might care to write a play about a prince of Denmark.”

Auden began pursuing poetry, an interest that stayed with him as he entered Oxford, where he connected with fellow poet A. L. Rowse. “From the very first I had no doubt of his genius,” Rowse recalled. “He would come to All Souls [College], his pockets stuffed with manuscripts of his poems to read to me and—though not of the idiom I was used to, not even [T. S.] Eliot—I could recognize a new and individual voice.”

Stephen Spender, another poet Auden met at Oxford, printed a collection of Auden’s poems on a small hand press in 1928. Later that year, Auden traveled to Germany, taking advantage of his father’s offer to support him while he lived abroad. His time in Berlin during the dying days of the Weimar Republic gave him his first major introduction to left-wing politics.

His poetry, though praised, wasn’t enough to support him, so for the next few years, Auden taught and wrote for magazines, too. Like many writers and artists of the left, he traveled to Spain during the country’s civil war, broadcasting on behalf of the republic and penning a poem, “Spain,” that became a touchstone of the cause.

The poem, which Auden later regretted, was criticized for glorifying bloodshed with its reference to the “conscious acceptance of guilt in the necessary murder.” Others read the lines “History to the defeated / May say Alas but cannot help or pardon” as a suggestion that whoever wins a war is always the most deserving of victory. As Auden himself put it many years later in a critique of the poem, the wording seemed to “equate goodness with success.”

“Auden was never comfortable in his role as poetic prophet to the British Left, and he was often most divided when he sounded most committed,” writes Mendelson. “As early as 1936 he sensed that if he were ever to escape the temptations to fame and to the power to shape opinion that led him to accept his role, he would need to leave England.”

That’s perhaps the most charitable explanation for Auden’s move to America in 1939. Others couldn’t help noticing that his departure coincided with the start of Britain’s ordeal in World War II. Novelist Evelyn Waugh would later claim that Auden had left “at the first squeak of an air-raid warning.”

His absence from England even came up in the British Parliament, although the government took no action against him. “In Britain,” says Carpenter, “some of those left-wing intellectuals who had supported and admired Auden during the 1930s were beginning to be shocked by his decision to remain in America.”

Auden, Carpenter concludes, “does not seem to have faced the question whether he had a moral duty to help, however trivially, in the fight against Hitler.”

“In Auden’s case,” Smith writes of Auden’s move to America, “it was probably not cowardice: Those who knew him are firm in their rejection of that charge.”

In many other aspects of his life, Auden displayed firm moral conviction. He grew disillusioned with politics as a remedy for the human condition, returning to the Anglican faith of his childhood as a personal compass. Mendelson has extensively documented many acts of kindness that Auden quietly performed as an expression of his Christian faith. When an elderly woman in his Episcopal congregation in New York City was experiencing night terrors, Auden “took a blanket and slept in the hallway outside her apartment until she felt safe again,” Mendelson tells readers. After World War II, Auden paid for school and college costs for two war orphans. At literary gatherings after he became famous, Auden sought out, says Mendelson, “the least important person in the room.”

His grandest act of generosity might have been marrying Erika Mann, the daughter of novelist Thomas Mann, to provide her with British nationality and save her from the Nazis. The nuptials were nothing more than a formality, since Auden was gay and counted as his real marriage his long relationship with the American poet Chester Kallman.

Auden’s spirituality didn’t incline him to piety. He smoked and drank heavily and used amphetamines to fuel his literary output. During his New York years, Auden became friends with Oliver Sacks, the neurologist who would later become a celebrated author himself. “He was a very heavy drinker,” Sacks recalled of Auden, “although he was at pains to say that he was not an alcoholic but a drunk. I once asked him what the difference was, and he said, ‘An alcoholic has a personality change after a drink or two, but a drunk can drink as much as he wants. I’m a drunk.’”

He was notoriously untidy, so much so that he “reduced any room he was in to a shambles,” Rowse writes. When composer Igor Stravinsky’s wife, Vera, visited Auden and Kallman for dinner, she found a bowl of brown gunk in the bathroom and flushed it down the toilet. She later learned it was the evening’s dessert—some chocolate pudding that had been placed on top of the commode to cool.

When Smith attended one of Auden’s readings, the poet rose to the stage with his fly undone. “The fact that he was a sartorial disaster,” Smith recalled, “wearing a stained and ash-spattered suit and battered carpet slippers, in no sense detracted from the impact of his words.”

Although Auden seemed dissolute in many ways, he was obsessively punctual and kept to a strict work schedule. “Routine, in an intelligent man, is a sign of ambition,” he observed.

“Auden rose shortly after 6:00 a.m., made himself coffee, and settled down to work quickly, perhaps after taking a first pass at the crossword,” Mason Currey tells readers of Daily Rituals, his survey of the professional habits of great writers and artists. “His mind was sharpest from 7:00 until 11:30 a.m., and he rarely failed to take advantage of these hours. . . . Auden usually resumed his work after lunch and continued to work into the late afternoon.”

Auden’s personal contradictions make him a difficult man to fathom. His poems, like the poet himself, can defy easy understanding, too.

“Funeral Blues,” for example, seems a simple and straightforward composition, but it has a complicated history. The poem originally appeared in The Ascent of F6, a play Auden wrote with Christopher Isherwood. In the play, the poem’s lines of memoriam are voiced ironically, advancing a point about how tragedy can be manipulated for political gain. Since then, however, “Funeral Blues,” which was conceived to underscore some of humanity’s most cynical impulses, has been popularly embraced as an earnest expression of heartfelt loss.

Auden knew that poems could speak to audiences in ways not originally envisioned by a writer. “We often derive much profit,” he wrote, “from reading a book in a different way from that which its author intended but only (once childhood is over) if we know that we are doing so.”

Maybe, on some level, Auden was resigned to the idea that readers, not writers, ultimately determine the future of a poem once it’s published. As he wrote in his poem about Yeats, “The words of a dead man / Are modified in the guts of the living.”

So perhaps Auden wouldn’t be surprised that “September 1, 1939,” a poem he essentially disowned, is one of his best remembered. Penned to mark the outbreak of World War II, the poem had a renewed profile after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Auden came to dislike “September 1, 1939,” especially its much-quoted assertion, “We must love one another or die.” The line later seemed nonsensical to him, since people must ultimately die regardless of their actions.

Even so, in the wake of 9/11, readers found consolation in stanzas like this:

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

The promise of the poem, that a single voice can relieve the anguish of a broken world, is one reason that readers still turn to W. H. Auden. His own voice, darkly complicated but ultimately affirming, points us to the possibilities of the individual mind struggling to sort things out.

“He can be with us in every part of our lives, showing us how rich life can be, and how precious,” Smith writes of Auden. “For that, I am more grateful to him than I can ever say.”