Curator Robin Jaffee Frank has cast a wide net at Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum, and appropriately so. In the museum’s exhibition “Visions of an American Dreamland,” Coney Island is a fun house mirror in which much of America, its psyche and dreams, its brash beauties and troubling realities, stands reflected.

“It is blatant, it is cheap, it is the apotheosis of the ridiculous. But it is something more: it is like Niagara Falls, or the Grand Canyon, or Yellowstone Park; it is a national playground; and not to have seen it is not to have seen your own country.” So wrote a reporter for Hampton’s Magazine in 1909. Frank makes clear that, though no longer a national playground, Coney Island continues to occupy a disproportionate space in the national imagination.

Frank has her own history with Coney Island. It was there that her parents dated before they were married, and there that her father said good-bye to her mother before heading overseas in World War II. Frank herself spent many days of her Brooklyn childhood there with her cousins. But it wasn’t until she was a senior associate curator at Yale University that she felt the broader impact. Staring at the Joseph Stella painting Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras in the university art gallery, she felt herself drawn into that vortex of whirling remembered details and colors. It was 1992, and she proposed an exhibition. The idea lay dormant while she built her career, but in 2011, as chief curator of American paintings and sculpture at the Atheneum, she received a planning grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and “Coney Island, Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008” finally began to take shape.

The result is a show that is a show. Like its inspiration, this exhibition grabs visitors at the door and pulls them into a world of flash and glitter, of fantasy and transgressive visions, of sounds and light and reinvention.

Reinvention, in fact, has been Coney Island’s one constant. Its life as a recreational space began as a watering hole and get-away for the well-to-do and for artists, as the paintings in the exhibition’s first room, “Down at Coney Isle, 1861–94,” make clear. When not seeking inspiration in Europe or the Middle East, for example, Sanford Robinson Gifford, a leader of the Hudson River School, found time to paint The Beach at Coney Island; the crystalline light of this scene, such a contrast with the moodier atmospherics more characteristic of his landscapes, perfectly illuminates the fashionably dressed couples strolling on the sand.

Yet already there is a hint of something different—the African-American couple standing slightly apart in Samuel S. Carr’s Beach Scene from 1879, and looming in the distance, across the dunes in William Merritt Chase’s 1886 Landscape, near Coney Island, a monstrous elephant, a seven-story tall, “zoomorphic” hotel, notorious not just for its form but also for rooms that rented by the hour. A place where the customer could buy a cigar and contract an assignation in the pachyderm’s front leg, then climb a spiral staircase in the back one to a guest room above, and afterwards relax with a view through a telescope in the elephant’s eye or visit the museum in the left lung.

“A fantastic city all of fire [that] suddenly rises from the ocean into the sky. Thousands of ruddy sparks glimmer in the darkness, limning in fine, sensitive outline on the black background of the sky, shapely towers of miraculous castles, palaces and temples. . . . Fabulous and beyond conceiving.”

So wrote Russian revolutionary Maxim Gorky in 1907; although impressed, even overwhelmed, he was also repelled, dismissing Coney Island as an “opiate of the masses.” Which it surely was, for with the birth of the twentieth century and the coming of railroads, the fashionable resort morphed into a middle-class escape and afterward a midway for the working class.

“For five cents,” reported Fortune magazine in 1938, “Coney Island will feed you, frighten you, cool you, toast you, flatter you or destroy your inhibitions. . . . In this nickel empire boy meets girl.”

And much more, as the exhibition makes clear. In a bird’s-eye view of Steeplechase Park, painted by the otherwise unknown Leo McKay (and cleaned and restored with funds from the NEH grant) you see the whole fifteen acres of the Coney Island venue, where in 1897 the modern amusement park, arguably, was invented. You entered through the “Barrel of Love,” a ride that literally threw you into the arms of strangers, and from there floated down the canals of Venice, visited a bazaar that the Orient could not equal, rode a mechanical horse around the steeplechase track, flew to the moon or, depending on your proclivities, descended to Dante’s Inferno. And at night it was all lit up with the million-plus lights that had inspired Maxim Gorky—visible in this exhibition in a clip from the 1905 Edison film Coney Island at Night, directed by film pioneer Edwin S. Porter.

Movie-making grew up with Coney Island, as a gallery peppered with clips and stills bears witness. Its amusement parks had been some of the earliest venues for display of the early, primitive “Kinetoscopes,” “Mutoscopes,” and “Eidoloscopes,” and it soon proved irresistible to filmmakers who found in it a ready-made set of superhuman dimensions. Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle and Harold Lloyd shot the chutes (1917 and 1928); King Vidor filmed James Murray proposing to Eleanor Boardman in his ground-breaking silent The Crowd (1928); and Robert Cummings courts Jean Arthur on the Coney Island beach in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941). More recently, filmmakers Woody Allen, Paul Mazursky, and Spike Lee have shot there as well.

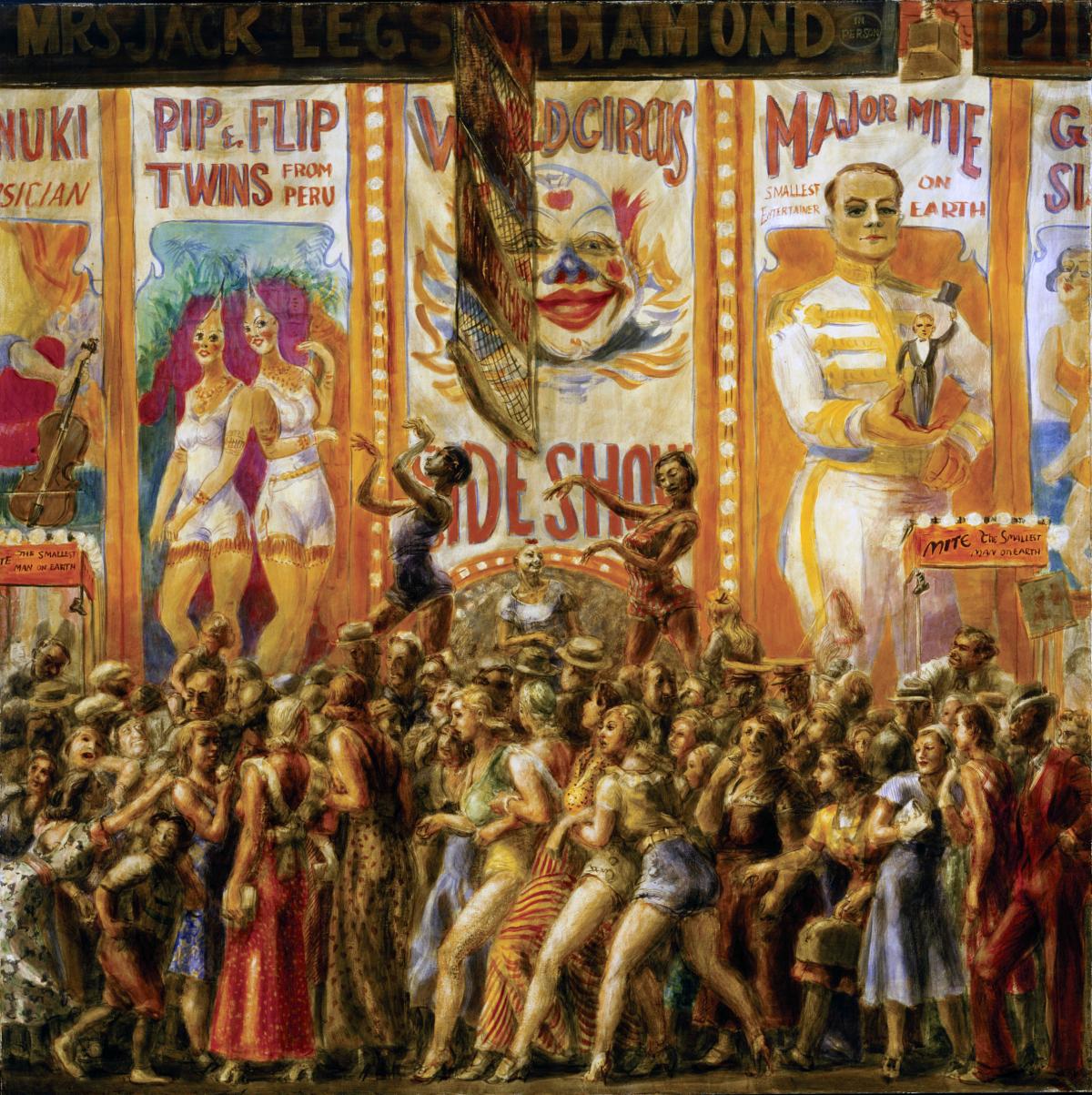

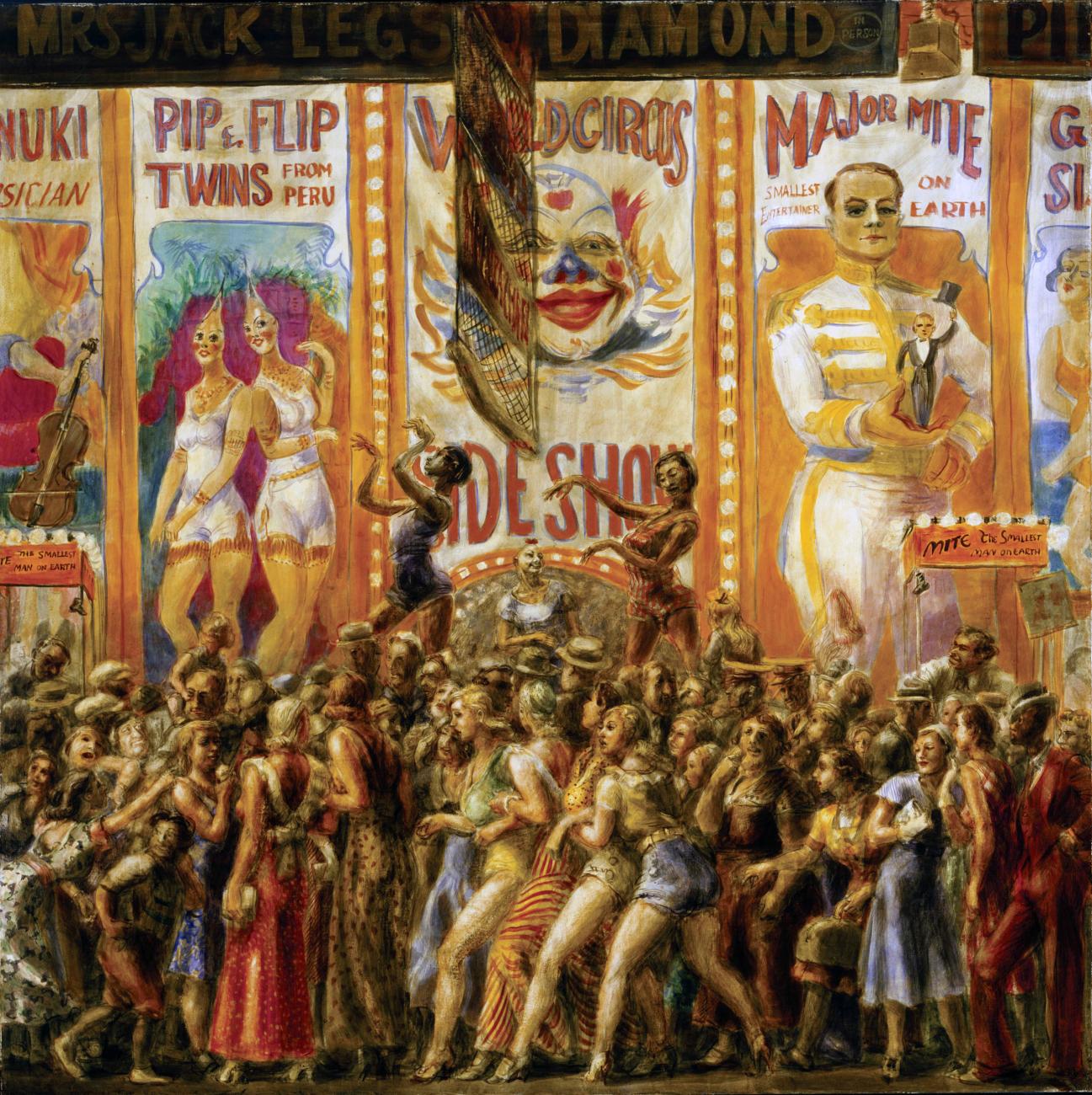

Not all is romance or comedy at Coney Island, however, or in this exhibition. There is a dark side to the American dream, a relish for the horrifying and brutal. Edison sent a crew here to film the execution of an elephant by electrocution in 1903, and Tod Browning still horrifies with his 1932 minor masterpiece Freaks, whose stars were Coney Island’s side show performers. In the banners advertising “Jeanie Living Half Girl” and “Quito, Human Octopus” we see reflected our own humanity and vulnerability, albeit strangely altered. This, surely, was one reason that artists such as Reginald Marsh were so drawn to this aspect of the island; in his tempera paintings such as Pip and Flip and Smoko, the Human Volcano, Marsh echoes the colors and deliberate grotesqueries of the Coney Island banners as audience and performers merge almost indistinguishably into a giant, milling sideshow.

“Coney Island is only another name for topsyturvydom,” wrote the prominent arts critic James Gibbons Huneker in New Cosmopolis in 1915. “There the true becomes the grotesque, the vision of a maniac.” That, judging by the works hung here, was a large part of the appeal for artists such as Marsh, Harry Roseland, and Paul Cadmus. For the public as well—when a newly appointed Parks Commissioner named Robert Moses silenced the “ballyhoo,” meaning the carnival barkers, New Yorkers were outraged. “The beaches belong to the people to desecrate as they please, and they do not like to be whistled at when their conduct exceeds what seems to them an arbitrary propriety. Mr. Moses, we think, falls into the error of supposing that everybody likes the same things that he does—that the standards of beauty and pleasure are universal. This is arrogant. It is arrogant for any man,” A. J. Liebling scolded, “to imagine that he can landscape the human heart.”

“The subway pours the people of New York and its visitors—young girls with firm high breasts and pretty legs and shrill discordant voices—hat-snatching adolescents and youths on the make—children in arms and children in trouble—scolding mothers and heavy-suited, heavy-booted fathers—soldiers and sailors and marines—virgins and couples in love and tarts—Gentiles and Jews and the in-betweens—whites and blacks and orientals—Irish and Italians and Swedes and Letts and Greeks—pushing, plodding, laughing, jostling, shrieking, sweating, posing—shedding their identities, with their inhibitions, in the voice, the smell, the color of Coney Island.” So wrote the editors of Fortune, and it explains why Coney Island was a magnet for immigrants and a showpiece of immigrant talents and the immigrant experience.

Consider, for example, the masterful carousel horses in the exhibition, one carved by Solomon Stein and Harry Goldstein, circa 1912–17, the other carved by Charles Carmel circa 1914. The styles are very different: Stein and Goldstein’s horse is heavily stylized, encased in armor, while Carmel’s is vital and free, head thrown back, body lifting as if about to rear. Yet there is an iconic look to both, and in fact all three carvers were Jewish refugees from Russia who had learned their trades decorating synagogues.

Immigrants are heavily represented, as well, among the artists in this show. England, Germany, Bohemia, Hungary, and Japan—they came from all corners to document the melting-pot experience and to shape it themselves at Coney Island. Joseph Stella, for example, brought the Futurist vision from Italy and Paris to his inspirational canvas of battling lights; Siberian-born Abraham Walkowitz examines attitudes toward racial mixing in his Sideshow at Coney Island, where a crowd of white patrons stare at the alternating black and white figures on the stage. In what may be the ultimate immigrant statement, Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank came to Coney Island on July 4, 1958, ostensibly to capture a celebration of independence and instead, in a series titled Coney Island, Fourth of July, found the dispossessed sleeping on the sand, and wandering the streets in bitterly ironic comic hats.

Coney Island had become not just a place to experience the exotic and to reinvent yourself, but also to imagine the future, and as such, notes curator Frank, it “changes not just America but much of the modern world.” The playground’s appetite for novelty—faster, more daring rides, more dazzling lights, colors, and illusions—was insatiable. Space travel was a particularly persistent dream—both Steeplechase Park and its younger competitor Luna Park had featured an imaginary flight to the moon among their attractions. But something much closer to the real thing emerged in 1962 with Astroland Park, Coney Island’s three-acre response to President Kennedy’s call to put an American on the moon. It wasn’t until 1969 that Apollo 11 deposited Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the actual lunar surface. In the meantime, though, tens of thousands had flown there, at least in their imagination, in Astroland’s Cape Canaveral Satellite Jet. Closed in 2008, the park’s surreal scenery survives in photographs on the Atheneum walls, shot by luminaries Abe Feinstein, Charles Denson, and Frederick Brosen.

Although Astroland, like so much represented in this show, has perished, to dismiss any or all of this as nostalgia would be a mistake. Artists continue to create at, and about, Coney Island. Contemporary works have been on display in a host of satellite exhibitions organized by other regional organizations such as the Yale University School of Art, Real Art Ways in Hartford, and the Westport Arts Center in Connecticut.

As Frank points out, Coney Island always has been a prism through which an extraordinary array of artists have viewed the American experience. In songs, movies, literature, painting, and sculpture, Frank says that Coney Island continues to be “a vehicle for artists to examine themes of changing ideas about leisure, that supported the mixing of peoples of different races, ethnicities and classes, transcending social boundaries, and those are all themes that are not about the past but very much with us in the present.”