“Jews,” Rutgers University’s resident Yiddish scholar Edward Portnoy said with a straight face at the Society of Illustrators last April, “are not funny.” At least not to their Gentile observers of the nineteenth century. European literati such as Thomas Carlyle chorused that the Jews had absolutely no sense of humor. French philosopher and Middle East scholar Ernest Renan even went so far as to say, “Semitic people lack the faculty to laugh.” The Jewish people themselves, however, thought they were hilarious, more hilarious than anyone else. So how did a people whose nineteenth-century stereotype consisted of a grave Talmudic scholar come to dominate American comedy? When did the rest of us get in on the joke?

These were the questions that the enormously successful Manhattan event, titled “From the Borscht Belt to Seinfeld: The Evolution of Jewish American Comedy,” tried to answer. The presentation was funded by the New York Council for the Humanities and featured a panel of experts who provided historical and personal context on the topic. The panel, which consisted of Portnoy, veteran comedian Larry Storch, contemporary television writers Bill Persky and Tom Leopold, and illustrator Drew Friedman, convened as an extension of Friedman’s exhibit of caricatures. This exhibit represented the culmination of Friedman’s three volumes of portraits of old Jewish comedians, the last of which was published in 2011.

When large waves of Jews from Eastern and Central Europe flooded into America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they were quickly initiated into the American brand of racial humor. To homegrown Americans, these foreigners looked funny: their dark hair and beards, their distinctive noses. And their Yiddish, by many accounts, sounded comical too. It is from their Hebrew-German linguistic brew that we get some of English’s most phonetically apt words like schmuck, glitch, and chutzpah. All of this made them easy targets of ethnic-based mockery. To the regrettably popular blackface comedy, American comics added the Jew-face. They put on putty noses and false beards and made jokes about Jewish shopkeepers setting their businesses alight for the insurance. Instead of resenting this kind of racial comedy, Jewish entertainers decided that they would be better at making fun of themselves than anyone else. Jewish comics honed their skills first to Jewish-only crowds in New York City, then later in the Jewish-dominated resorts of the Catskills, known as the Borscht Belt, and finally into mainstream American consciousness. American comedy greats such as Mel Brooks, Woody Allen, Sophie Tucker, and Billy Crystal all got their start in the mountains of southeastern New York, parodying their own Jewishness and everyone else. It is in this self-aware, self-deprecatory vein that Friedman and the Jewish humorists he caricatured worked as well. From his portraits one can tell that Friedman—and his subjects—know that funny people have funny faces, and any good comedian would be crazy to not capitalize on this, even at the expense of their own vanity.

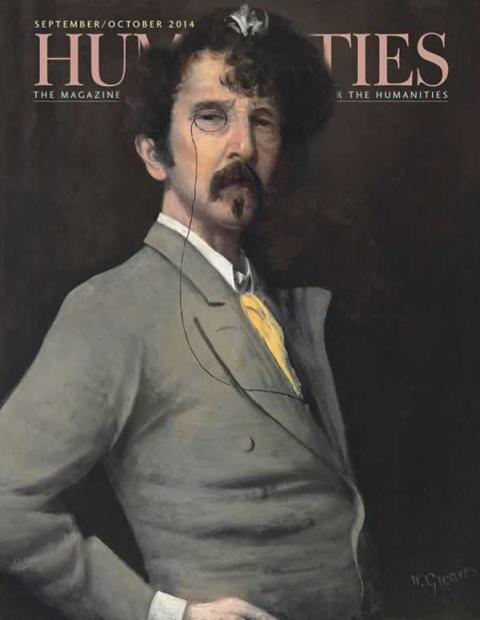

Friedman, dubbed the “Vermeer of the Borscht Belt” by Steven Heller in the New York Times Book Review, specializes in caricature. His work has appeared in publications such as the New Yorker, Rolling Stone, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and MAD magazine. Jewish himself, Friedman stood at the podium grinning and facetiously pointing out that “this panel, and show, [was] proof that Jews do run the world.”

There was a distinct sentimentality and nostalgia to the event. “I never thought of myself as old,” Persky said, until “I realized I had worked with just about everybody on these walls.” Ninety-one-year-old Storch still marshaled the genius repertoire of impressions that made him famous in the Catskills sixty years ago. He described his childhood growing up in the boroughs of New York City with his father, an immigrant from Poland. “Pop, where’s the Himalayas?” Storch asked one day after school, to which his father responded distractedly, “Put things away; you’ll know where to find them!” And despite his irreverent illustrations, it is clear that Friedman maintains profound respect for the real people behind the portraits.

In its audience, its subject matter, its history, its art, its sentiments and irreverent wit, this occasion was an intensely New York affair. New Yorkers from all generations “have a real affinity for this kind of comedy . . . they grew up watching it,” says Anelle Miller, executive director of the society. But more than that, this event was an homage to all artists’ dedication to their craft. One can see it in Friedman’s meticulous portraits and in the careers of the old Jewish comedians who peppered the walls and quipped at the podium.