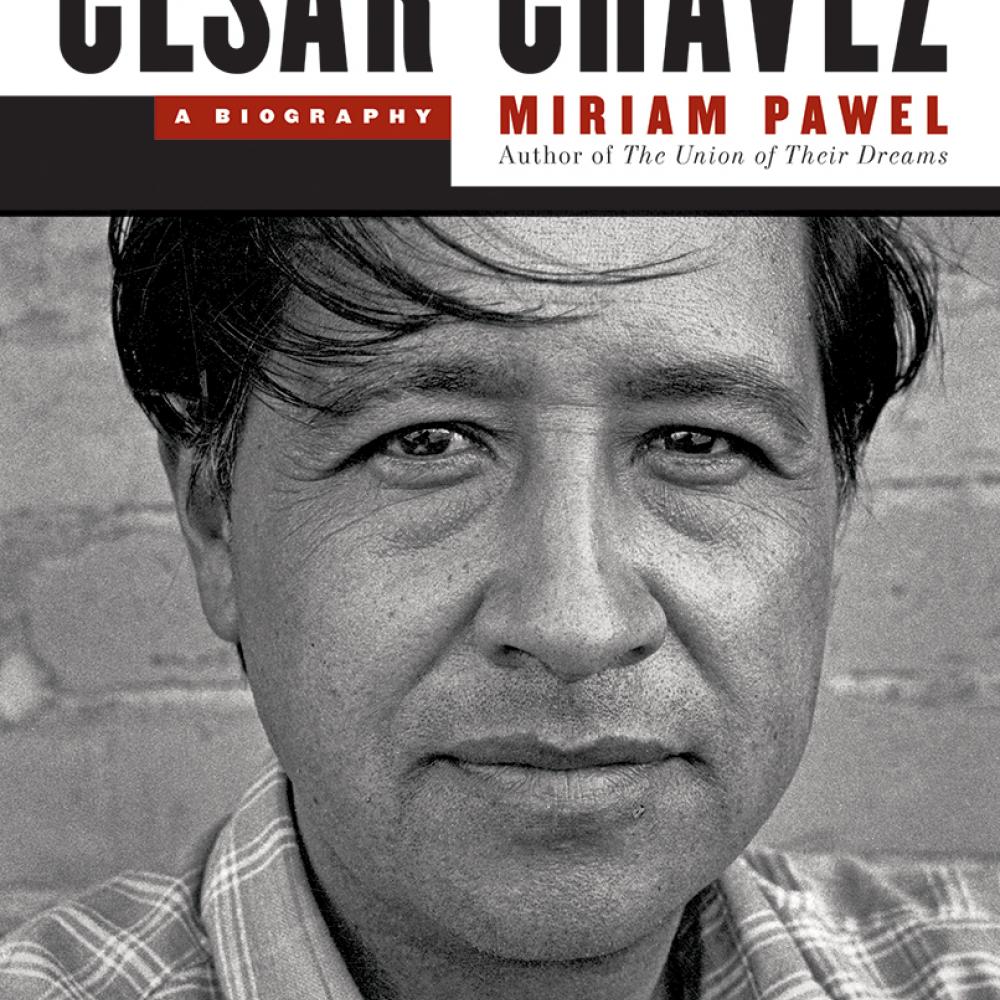

Images of Cesar Chavez are an indelible part of the American consciousness of the latter twentieth century: In a black-and-white still from 1968, the founder of the United Farm Workers breaks a twenty-five day fast by meekly accepting a morsel from the hand of Robert F. Kennedy; in July 1969, Chavez looks out from the front cover of Time with a visionary gaze; from within the deckle-edged borders of a commemorative postage stamp, his engaging smile beams warmly; and in countless newspaper photos, he stands, speaking before a quiver of microphones, with the angled-off wings of the UFW Aztec eagle spreading out powerfully above his shoulders.

For every positive image of Chavez, though, there’s another one that paints a different picture, as Miriam Pawel brings to light in her meticulously researched, NEH-funded biography, The Crusades of Cesar Chavez. The union organizer was vehemently opposed to undocumented immigrant workers, looked with disdain upon the material comforts his own union members yearned for, and slipped into despotic isolation at his California mountain compound, La Paz, purging the UFW of many of his closest friends, allies, and mentors.

Reviewers have noticed Pawel’s disciplined approach to her oft hallowed subject, avoiding as it does, a hagiographic treatment that otherwise could cast Chavez in an uncritical, even saintly, light.

Pawel, notes the Economist, “does not shy away from the more troubling sides of her subject.” Even as the British weekly acknowledges one of Chavez’s most enduring accomplishments—“crippling consumer boycotts” that “drove intransigent growers to negotiation and sometimes capitulation”—it is quick to add that “Chavez was a media-savvy pragmatist not averse to dealmaking. Yet unlike the hard-headed Anglos who ran the industrial unions, he saw himself more as a spiritual guide than a labor leader.” And regarding infighting or Chavez’s lack of a sense of solidarity, the reviewer notes, “He distrusted colleagues who sought pay raises, and rejected them for himself; sacrifice, he urged, must be the mark of the movement. . . . Gandhi, rather than King, was the role model.”

“In the 1960s and early ’70s,” writes Thomas Geoghegan in the New York Times, “Chavez did seem like a version of Gandhi.” “Organizing the dispossessed, our own untouchables, he fasted to the point of death, staged mass marches up and down California that resembled religious pilgrimages, and defeated growers with nationwide boycotts that even Gandhi would have found hard to duplicate.” Geoghegan adds that “after an early heroic phase, he seemed to lose interest even in organizing.” Labor Noteswriter Mark R. Day concurs: “Pawel documents the fact [that] Chavez and his organizers could never really accomplish the union part. And at the end of the day, Chavez never wanted to do it. The fasts, marches, and boycotts worked magically—but once the contracts were signed, the union couldn’t competently administer the hiring halls. This generated backlash from both workers and growers.”

And yet, in her book, Pawel writes that Chavez “grappled with how to instill sacrifice as a value in the union’s staff, as well as its members. . . . The staff must set an example. ‘Then the workers who are in leadership positions [Chavez explained] may begin to get the idea of self-sacrifice, . . . It has to begin in your own life. ’”

Los Angeles Times reviewer Liza Featherstone assesses the ultimate impact of Crusades, noting that Pawel’s biography is “for readers who find real human beings more compelling than icons and history more relevant than fantasy.”