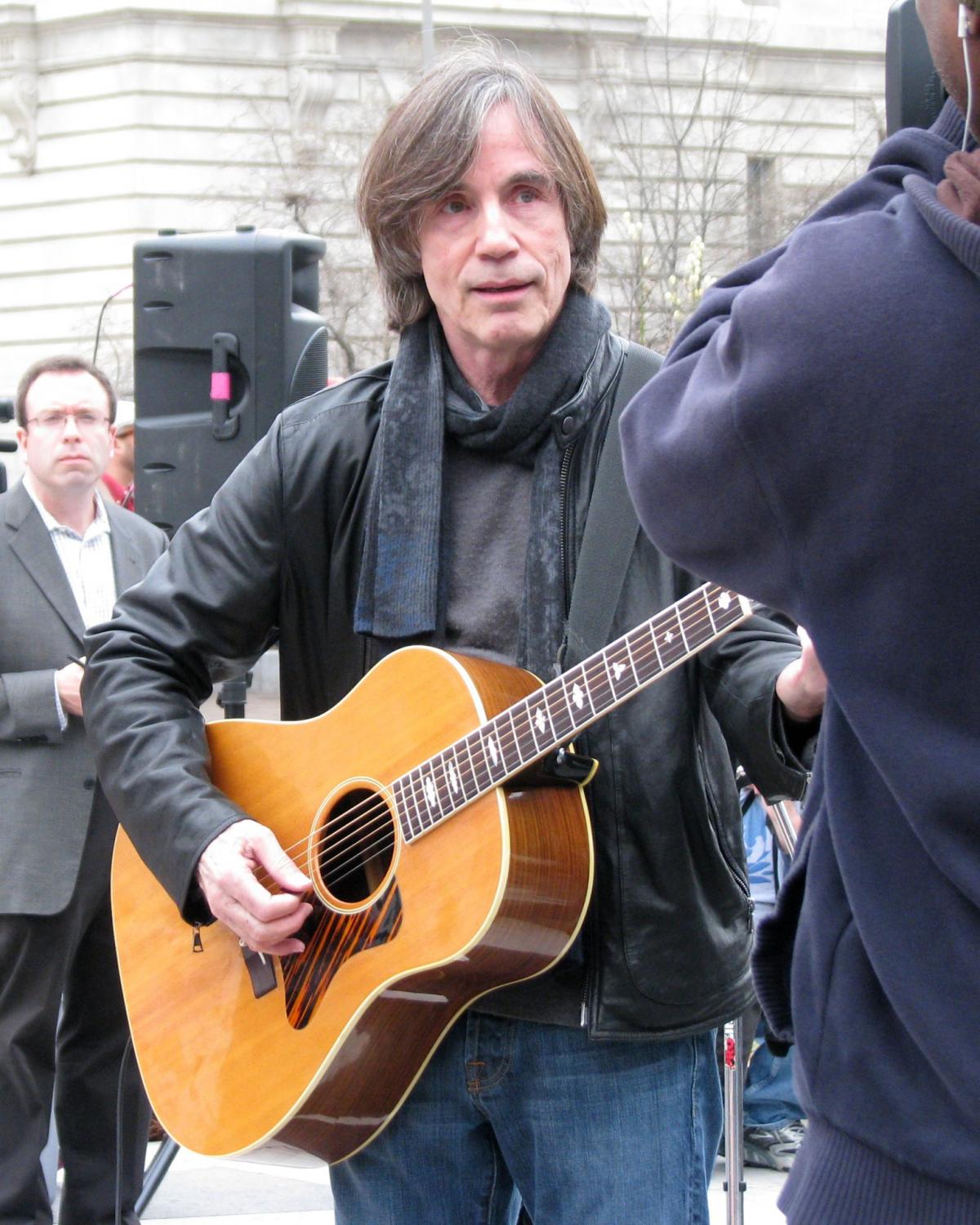

In early December last year when Jackson Browne came off tour, he made a beeline for Freedom Plaza in Washington, D.C. After tuning his guitar with some difficulty in the misty late-fall conditions, he performed for the Occupiers, with a makeshift Christmas tree of recyclables over his shoulder in the near distance and the U.S. Capitol looming farther down Pennsylvania Avenue. Afterward, while eating a donated lunch from the site’s food tent, the rock ’n’ roll hall of famer said, “My message is the same as the people who are speaking here. The issues that they raise . . . are issues that I believe need to be addressed.”

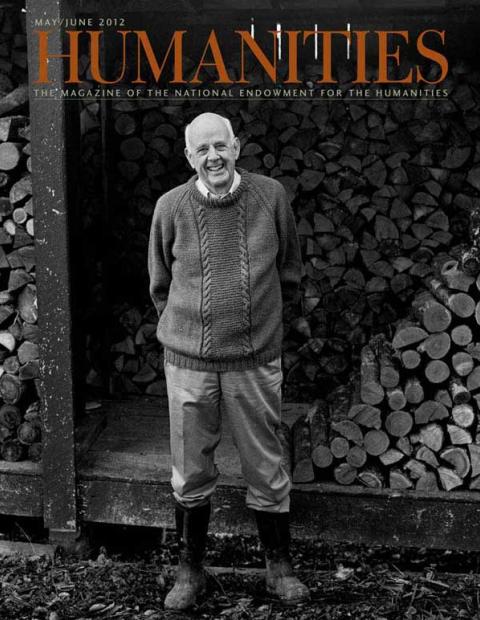

Paris in May 1968 throbbed with lyrics and slogans, too, during even more tumultuous times, but the question was, and still is, how much that movement was affected by its music and how much the rebellious times influenced the music that accompanied them. It may have been a current that ran in both directions, according to the NEH-funded research done by Eric Drott for his book Music and the Elusive Revolution (University of California Press, 2011), which is subtitled Cultural Politics and Political Culture in France, 1968–1981.

One of Drott’s best examples of this two-way path of influence is the work of cabaret artist Léo Ferré, who was in his early fifties at the time of les événements. “The poetic aspects of his mature style,” writes Drott, “were firmly entrenched” by this time, and the darling of the far left (he deeply distrusted hierarchy and authority of any kind) had fresh life breathed into his singing career from a new generation of admirers in May and June 1968. In other words, he simply became popular again to a new audience without, at first, doing anything necessarily new. His song “L’été 68” (Summer of ’68), though, soon offered much more than the blunt, predictable appraisals of events in most chansons révolutionnaires of the moment and boldly defined May 1968 in turn, treating “the theme of social conflict through metaphor and poetic allusion.” And in “Comme une fille” (Like a Girl) Ferré “casts insurrection as a quasi-natural urge.” As Jackson Browne was touched by the Occupiers in 2011, Ferré, an established performer long before the protests of May ’68, was deeply moved by the events in Paris in his own time. But, what is more, Ferré was affected artistically, even transformed, by the protestors’ concerns.

This might be enough for most general readers, in terms of understanding the complex back-and-forth between politics and culture, but Drott also takes on the much less well-known effects of May ’68 on free jazz, French rock, and contemporary classical music. Those genres, Drott writes, were greatly influenced by cultural intervention which “offered members of the contemporary musical community new professional opportunities as well as a way of legitimizing their activities.” Through what was known as “the long seventies,” utopian dreams of another revolution (the one in ’68 had come to be regarded as failed and its benefits elusive) were kept on life support until the surprising day in May of 1981 when socialist François Mitterrand defeated Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, bringing about what many on the left regarded as a “successful May ’68.” But then, Drott concludes, with the hard realities of governance staring the Socialists in the face, utopian projects, musical or otherwise, became increasingly difficult to sustain, prompting the quip “May is finally dead . . . Long live May!”