BRUCE COLE: Let’s see. You’ve been a historian for the National Park Service. You’ve written two important biographies of major Civil War figures, and you have also been a highly decorated civil servant and have been on the scene for some incredibly historic moments. But what would you call yourself—an historian, a biographer, a diplomat?

ELIZABETH BROWN PRYOR: I don’t know if I could categorize myself as one thing. They have melded into each other. And they have been mutually reinforcing.

I am very proud of having been associated with the National Park Service, because they do a marvelous job overall, often under political pressures and resource pressures. The amount of research that goes into restoring historic sites and into the interpretation of them for large public audiences is extraordinary.

I was fortunate to start in the department of interpretation at the Park Service, where I learned how to analyze—not critique, which I think of sometimes as a failure of academic systems—but to analyze, to take a lot of material, sift through it, try to figure out what you think about its truth or what the significant thread is—and then present it effectively.

Later I was living out real history, real-time history, in a lot of the jobs that I had. At the State Department, I had to move at the heart of a lot of very problematic issues. And that affected my interest to go back and write more history. All that see-it-live experience and the responsibilities I’ve had have given me more appreciation for the dilemmas that historical figures have been in. I was in Sarajevo at the time of the siege, and I felt a kindred spirit with General Lee when he was at Petersburg and places like that.

COLE: You said you differ with academics—that what you’re interested in is analysis rather than critique.

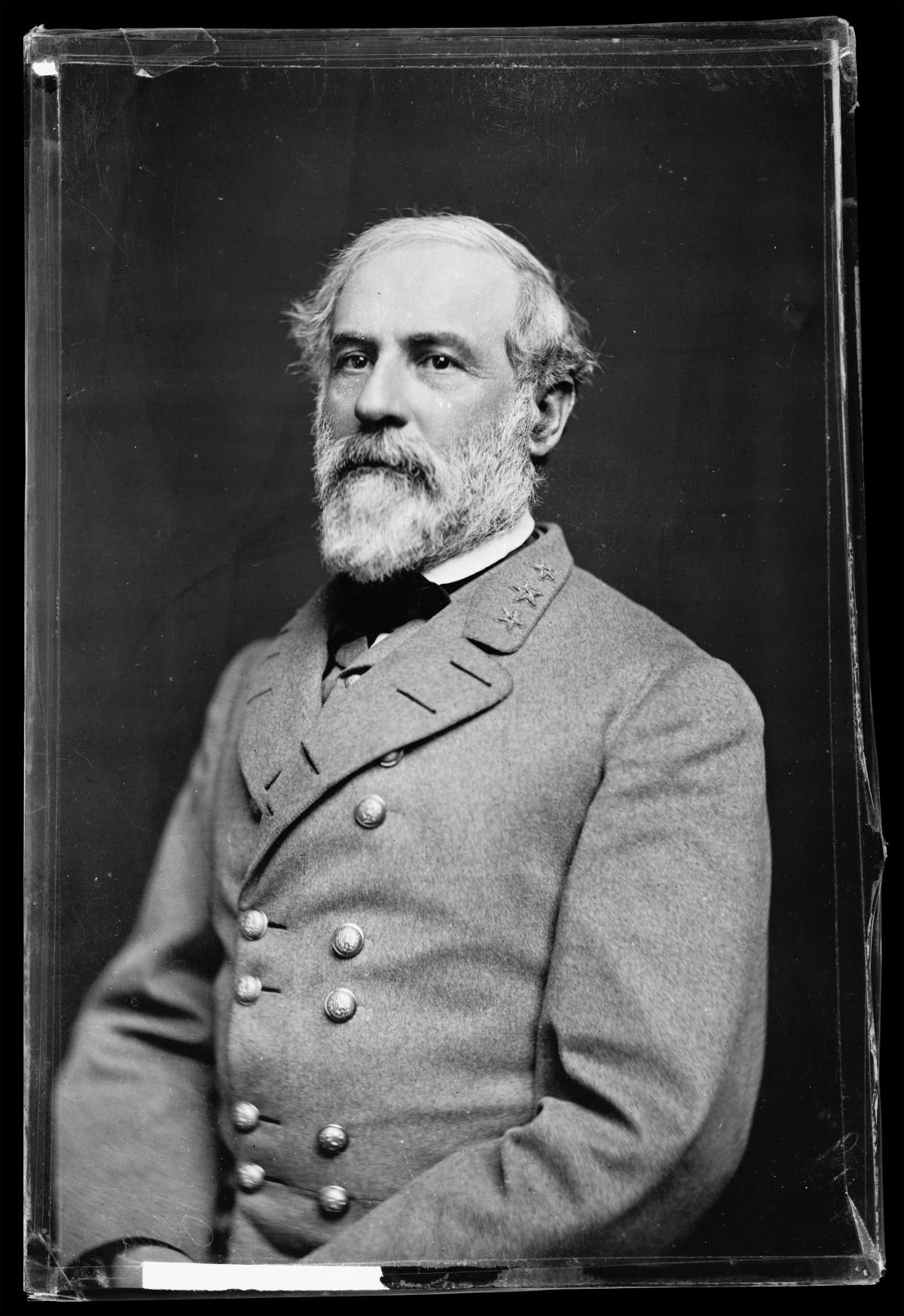

PRYOR: It’s very easy to critique things, to find the weak points or to assess small details to death and lose the larger vision. Critique is quite different from analysis. In my humble opinion, it’s a lot easier. It’s a kind of cheap, poor man’s version of analysis. I think the American system of scholarly training relies too much on what other people have said, on training people to respond to what others say, and often to pick those points apart. It’s not the same as original analysis. One of the things I’ve found in doing the book on Robert E. Lee was how little original research there had been. There are a lot of people who are doing what I call “retread history.” They just talk about what the last person said and what the person said before them. And not only does it make it easy to repeat errors, it’s not particularly stimulating. It’s not particularly original.

COLE: I like how you put that, “retread history”: talking about what the last person has written and then talking about what the last person before that has written and then moving farther and farther away from the actual subject, which is the original source material. How did you become interested in history? I have an idea that it has something to do with your home and your family.

PRYOR: Both my parents were very interested in history, and so our house was filled with history books.

COLE: Where did you grow up?

PRYOR: My family lived all over the United States. I was born in Gary, Indiana. We lived in Chicago, and we lived in the Midwest, San Francisco, New York. I went to three different high schools in four years. My father worked for AT&T, and companies in those days were more willing to send families all over the map.

My mother’s interest in history, I think, affected my family a lot because she’s a great storyteller. She grew up with a great-grandfather—my great-great-grandfather—who didn’t die until he was about 104. He was clear and sharp in his mind until the end and he had fought in the Civil War. He was from a border-state family, a Virginia family, but he lived in southern Indiana, and he fought for the Union. Well, she grew up hearing these stories sitting on a porch with Grandpa Kenly. We still have his letters and his discharge papers. We have had all kinds of things. But it’s really this set of stories that he told my mother—that she grew up with that caused her to think of the war as very real.

And what’s most remarkable is that Grandpa Kenly grew up with a great-grandfather who lived to be in his late nineties and who also was apparently bright and sharp until the end, who had fought in the American Revolution.

So, there are only three people between me and the American Revolution. I don’t feel too removed from it! It seems very immediate. And it was my mother’s storytelling ability—“history” means “story” after all—that got me hooked.

COLE: How old were you when you started hearing these stories?

PRYOR: I’ve always remembered them. You’re also from Indiana. Did you ever see “trail trees,” —trees that the Indians had actually grown as young saplings and bent over to mark the trail? I remember, as a kid, going to visit my grandparents in Indiana and, as we’d drive over, my mother would talk about these trail trees. History was always right there. Very immediate.

COLE: I see. You had these personal connections to history. The Revolution and the Civil War were not just events you read about in a textbook.

PRYOR: Well, my great-great-grandfather was at Shiloh. He was on the western front. Corinth, Shiloh. He was a foot soldier; he wasn’t an officer. And he was also part of the Union occupation of New Orleans, where Benjamin Butler made his famous pronouncement that if the ladies of the town didn’t behave as ladies toward his soldiers, they would be treated as “women of the town.” Which created a great furor. But, you know, Grandpa Kenly’s letters from New Orleans indicated there were a lot of ladies in that town who were just all too willing to go out and have a picnic and drink lemonade with the Yankees.

COLE: And you have these objects.

PRYOR: Yes, letters. We have only a handful now. I mean, we have a lot of documents and newspaper clippings. When he turned one hundred, a lot of people interviewed him for the newspaper and so on. But my mother remembers her great-grandmother Kenly, his wife—they got married during the war in 1863, and she also lived to some advanced age—going out in the backyard and burning a trunk of his letters because the kids had started to read them. They were love letters. And some of the ones we have, which are letters to her, are love letters.

He was a person of modest education. He says things like “we’re a-goin’” and it’s not just a way of speaking. He writes it that way: “We’re a-goin’ down the road, you know.” And so it’s almost a transcript of the way that people talked at the time.

COLE: These letters are from the same period that you’ve made your specialty.

PRYOR: The period that really interests me is what I call the early national period, between the Revolution and the Civil War. We call it the antebellum period in the South. The war itself had not interested me so much until I wrote about Clara Barton and wrote about Robert E. Lee.

It’s a very optimistic period overall even though it ends in cataclysm. And it’s a very literate period, a time when people are really becoming educated, not necessarily to a grand style. Like my Grandfather Kenly. But they’re educated, and paper is cheaper, and so writing becomes something that everybody can do. People who lived through these events in the Civil War clearly were compelled to write down what happened. What a wonderful resource of information, which we don’t have, say, for the American Revolution, when fewer people knew how to read and write, when paper and ink were hard to come by. When there was no post office to really send these things through. And we just don’t have that sense that the people who were there are telling us what it was like to be there.

COLE: Tell us about the work you did for the Park Service.

PRYOR: At the Park Service, I started out being a ranger, wearing the hat. My first job was running the elevator in the Washington Monument and taking dimes from visitors! I can still recite my part about the speed of the elevators: “The elevator you are now riding in reaches the top in one minute and something seconds.” Which was wrong, and everyone’s kid was counting the seconds. So I started out doing interpretation, dealing with the public and telling the story. And then I became a real historian for the Park Service and did a lot of background research for them, both on restoration of properties—I did very detailed, technical research almost, trying to find out when a pipe had been put in a house or how an onion was planted—and also doing some background research for congressional testimony. That’s how I got involved with Clara Barton, when her house was being acquired by the Park Service and it had to go through quite a series of steps in order to become federal property. And I wrote the congressional testimony for that.

I also wrote brochures, and I wrote booklets, some of which are still in use. It was very good historical training, because you have to be very precise about this material. When you restore a house or a property or a garden, it’s amazingly difficult to find information. Then you don’t want really to extrapolate from that; you want to be quite precise.

COLE: Then you actually knew about Clara Barton quite a bit before you began working on your book, correct?

PRYOR: When I was doing this background research for the congressional testimony, I found out a couple of things: One, there wasn’t a good biography of Clara Barton. There were memoirs from her contemporaries, like her cousins, early in the twentieth century, and then a few things written in the 1950s, but nothing we would consider an authoritative biography. There were also a number of things she had written, which turned out to be pretty suspect. I also found that she had left a monumental collection of papers.

COLE: But you also wrote agricultural reports for the Park Service.

PRYOR: Those were specifically for the National Colonial Farm, in southern Maryland near Fort Washington.

This was an attempt to give a more realistic picture of the way people lived in America in the eighteenth century. What happens is people go to Mount Vernon or they go to Monticello to see how colonists lived. But very few people lived that way. And so this was an attempt to show—literally—the kind of rough row you would have hoed as a small common farmer, trying to make a subsistence living in this part of the world. And the National Colonial Farm was put forward because it’s right across from Mount Vernon. So you can see people who are living on the same river at the same time period, but in a very, very different style.

What they wanted me to do was find out how people in the eighteenth century planted an onion and what were the varieties? How did they dig the hole? What kind of tools did they use? Did they have to import seeds or could they be acquired locally?

I did maybe a dozen of these reports. The first one was on fruit trees, apples, and so on. That was, I think, my favorite. It was the most fun to do. Apples are so evocative. It got into how they made hard cider and people getting drunk and all this.

Part Two: Affairs of State

COLE: How did you end up working for the State Department?

PRYOR: I had friends in the Foreign Service who encouraged me to take the exam. And I did have a kind of wanderlust. But, at first, I didn’t necessarily so much want to be in as to get in.

COLE: It’s like Everest.

PRYOR: Yes. So I took the test, and amazingly I did get in. I think the number one background for people who pass the test is not going to some school in international relations or a foreign service institute. It’s English. English and history. It’s almost all humanities.

COLE: Tell us about the State Department.

PRYOR: I was in for twenty-two years, and I had the good fortune, for virtually my whole career, of being involved with things that I was very proud to have been involved in and working with people who were stimulating and inspiring.

I spent most of my career in Europe, but I had everything from a very standard experience at our embassy in Madrid to being in a war in Bosnia, to being an arms control negotiator, which is what I spent a lot of my time doing. The backdrop was Vienna, but I didn’t see much of Vienna.

COLE: What arms control treaty were you working on?

PRYOR: It was the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. There were two negotiations involved with that treaty. I was in the first one, in 1989. This was initially a treaty between NATO and the Warsaw Pact. But governments were falling, one a day, around the table as we were negotiating, and you didn’t really even know anymore who you were negotiating with. The Warsaw Pact disintegrated during this time, and the treaty was ratified by sovereign states. The Soviet Union was still around—but it was still a very dramatic time.

Jim Woolsey was our chief negotiator, and this was one of his finest hours. It was a very high-priority item for the White House and they had handpicked all the people who were there. We were a small delegation, and we worked like little dogs. To work with people on something like that and to get the job done, to take it home, is pretty nice.

COLE: When you started your career, the Soviet Union was still a going concern. And when you left the State Department?

PRYOR: The whole world is a different place. Unfortunately, in some ways it’s as polarized today as it was during the Cold War. That period in 1989, ’90, ’91, ’92 was such an optimistic time.

COLE: It was the end of history.

PRYOR: We were very optimistic. The State Department had all kinds of innovative things during that period. I went to Moldova to help write the constitution. We had our laptop computers, and the talk would be something like, ‘What about this paragraph from the Swiss constitution? This is a good one here.’ I mean, it was a very heady experience to be doing this, and very optimistic. It hasn’t, sadly, all come out the way we would have liked.

We did all kinds of things, advised on bankruptcy laws for instance. Places that had had a government controlled by Communists didn’t have such things—and they were essential as they were trying to start up a market system. You can’t live as a small merchant if you don’t have laws that are favorable to creating an atmosphere that allows you to function. So, all kinds of crazy little things like that we were doing.

Well, Moldova was trying to realign its constitution. And we were there as advisers. But we were able to take the best from various constitutions. The American Constitution works for us and our specific situation, but it wouldn’t necessarily work in a place where language, say, was the issue. That paragraph was from the Swiss Constitution. We were looking at how the Swiss deal with different cultures and the four language groups that they’ve got. Moldova had language issues.

COLE: We can’t leave the State Department unless you talk about Bosnia.

PRYOR: I had tried to avoid trouble spots like Bosnia. But this is what makes the gods laugh, you know.

I was asked to go at the end of the war, after NATO had intervened. Sarajevo was a completely bombed-out city. I remembered seeing a place like that before, in pictures of World War II. No electricity or water or food. There was no food for a long time while I was there. When the bags of rice from the U.N. didn’t drop, there wasn’t any food.

I’ll tell you a story: I was staying in a house in Sarajevo, and there was a guy named Eddie, a guest worker from Germany there. I spoke some German, so that was our lingua franca. Eddie’s family had been living in this cellar for two years, in pretty dismal conditions because, again, there was no sanitation or readily available food. They rented me the top floor of their house, which they didn’t want to be in because it was too vulnerable to rocket fire. And we hadn’t had anything to eat for a while, and one night he brought me this bowl—what looked to me just like water—and he said: “You haven’t had anything to eat and this is what we eat when we haven’t had anything to eat for a while. It’s got a lot of minerals and vitamins in it.” I said, “What is it? It looks just like water to me.” He said, “No, no, it’s soup. We make this soup, we make it by boiling batteries.” And I said, “This is poison, you know.” “No, no,” he said, “you must eat it.” But this was the level that things were on.

People at the markets would line up around the block for a puff of a cigarette, pay 35 Deutsche Marks for that puff. And they had these cigarettes marked off with little marks so you could put it in your mouth, take one puff, and then you had to exhale. There was a guy there who had a sharp stick that he would poke in your chest to tell you to move on.

Happily, it came out pretty well. We were very lucky that we did the Dayton Agreement the way we did. It’s not a perfect agreement, but it was a blueprint, which is what we don’t have in Iraq right now, for instance. It told everybody who was in charge of every issue in that society. And since everybody had signed it, you could work, with great difficulty, to get them all to comply.

COLE: When did you write your book on Clara Barton?

PRYOR: I wrote Clara Barton in the early eighties. It took some doing to massage it into the way I wanted it to be. And then it was published in 1987.

COLE: I was just thinking about how your time in Bosnia was an example of what you said earlier about gaining firsthand experience.

PRYOR: Indeed. I took General Lee’s letters with me to Bosnia. We were still going in on those U.N. flights, and you could only take something like twelve kilos with you. You really had to pack like you were camping in the high Alps. But I took photocopies of some of my letters from Lee because I thought he’d be good company. You know, he spent some Christmases alone, and he’d been responsible for sending a lot of people to places from which they weren’t going to come back. And that’s very hard to deal with.

COLE: Is Clara good company?

PRYOR: Clara’s very good company. She’s kind of a whacky, eccentric individual. She’s probably not as good company as General Lee, but she’s probably the more important American.

COLE: Really? Why do you say that?

PRYOR: Because she left so many things that touch everybody’s life every day. Free education in Massachusetts and New Jersey didn’t exist until she fought for it. There is evidence that she was the first female employee in the history of the U.S. government. She worked on voting rights for blacks, voting rights for women. Of course, she did incredible work during the Civil War and changed the whole way the army structured its medical operations. All the work she did after the war on missing men: It was the first time that somebody had actually recognized the importance of individuals—not dumping people in mass graves, but accounting for every individual. And she was very eloquent talking about that, spent many years identifying tens of thousands of not just graves, but people—found people who had been listed as missing as a result of the war. This turned into the Office of Missing Soldiers.

COLE: Everyone who can should go out and visit her house in Glen Echo, Maryland, because it gives you a really strong sense of her personality.

PRYOR: It’s from her Red Cross period. The Red Cross was, of course, a tremendous thing to have brought to the United States. She had to lobby for many, many years to overturn the tradition that the United States didn’t sign international treaties. And she changed the Red Cross too. The Red Cross was really founded just for battlefield work. This idea that the Red Cross should go to a tsunami or a hurricane or a flood or whatever was Clara Barton’s idea. And, as a matter of fact, the amendment to the international agreement was named in her honor.

Emergency preparedness, the idea and the name, came from her. You don’t just take and give blood when you need the blood; you have a bank of it. You store up supplies so that when disaster strikes, you’re ready to go. She pioneered all this. The idea of first aid. Even the name “first aid” she made up, and the whole idea that citizens could be trained to give at least basic care in an emergency and that people could have a little kit, like we all do—band-aids and all that—this is Clara Barton.

Everybody’s life is better every day because of her. And I can’t say the same thing about Robert E. Lee. Although he’s a very important historical figure, I can’t find that same transcendent importance in society or that visionary quality.

Part Three: Burying the Dead

COLE: This is a bit of an aside, but one person who was interesting but underappreciated is Meigs, Montgomery Meigs.

PRYOR: Aha. He’s a little bit of a nemesis to the poor Lee family.

COLE: Exactly.

PRYOR: I’ve seen his papers. I read a lot of his letters because of the National Cemetery issue. He had been a friend of the Lees before the war. And his handwriting is unreadable. It’s no wonder there has not been a good deal written about Montgomery Meigs.

PRYOR: You know, he was a great architect.

COLE: Right.

PRYOR: He also developed a sauna system. Very inventive, creative guy. He’s ate French toast with cucumbers and salad dressing for breakfast. An original.

COLE: I think he was a genius.

PRYOR: He was an engineering genius.

COLE: He was quartermaster general during the Civil War. And made possible a lot of Union victories.

PRYOR: Yes, he was a brilliant quartermaster general. Lincoln absolutely revered him. So did Stanton. He was very interested in the development of the city of Washington, too, and he designed the Pension Building-now home to the National Building Museum.

COLE: Which is a wonderful building.

PRYOR: It’s got the Union Army marching around it, in the exterior frieze. And he designed the Aqueduct Bridge in stone, which was the largest masonry arch in the world. I mean, he was an engineering genius: irascible, difficult, got fired from being engineer of the Capitol.

COLE: Right. He was the guy who brought in Constantine Brumidi.

PRYOR: Oh, was he?

COLE: Yeah, I think he’s the guy who actually found him and commissioned him to do the decoration of the Capitol. His son was killed in the war. His son’s monument is in the Pension Building. But, as you say, he knew Lee before the war.

PRYOR: Yes. As young lieutenants, they surveyed the Mississippi River together. In a letter to his best buddy, Jack Mackay, Lee describes Meigs as “a host unto himself.”

I don’t know that they got along that well, but the Meigses used to go up to Arlington and take tea. Their subsequent enmity is emblematic of the many, many tragedies of the war. Meigs hated the U.S. Army officers who left the U.S. Army and joined the South. He hated them. He just never forgave any of them. In Lee’s case, he felt particularly angered because he thought after Gettysburg it was clear the war was over and he held Lee personally responsible for continuing the war and for these shocking, staggering numbers of casualties that they had, especially in the spring of 1864. His son died in October 1864.

COLE: Meigs’s?

PRYOR: Meigs’s son. Meigs was responsible for burying all the bodies that were being brought up from the wilderness by boat here to Washington, because the cemeteries were all full. So, he had a genuine problem on his hands. Lincoln asked him, “What are we going to do with Arlington? You know, Lee is still alive. Are we just going to give it back to him? Are we just going to let these people live there?” Lincoln had no good feeling for Lee; he mentions him by name as one of the reasons for suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. But Meigs says, “well, you know, Roman soldiers threw salt over the fields of their enemies so they couldn’t use them again, but I say let’s make it a field of honor, let’s bury our dead there”—with the understanding that this would be enough probably to keep the Lee family away. But Arlington was gigantic. So they could have buried people a long way away from the house, which is in fact what they did at the beginning. And this is one of the reasons I was going through this treacherous handwriting of Meigs. I was trying to see if there was real maliciousness in his desire to take Lee’s property over in such a way that the Lee family could never return. It appears that there was malice because when his soldiers buried the bodies far away from the mansion—so far away it wouldn’t really have made any difference to the Lee family—Meigs came and wanted them moved. He personally had bodies disinterred and reburied around Mrs. Lee’s flower garden.

COLE: Arlington was Lee’s . . .

PRYOR: Wife’s house.

COLE: Right. And she was a Custis, right?

PRYOR: Right.

COLE: So, she’s related to George Washington.

PRYOR: That’s right. Actually Martha Washington through Martha’s first marriage. There are huge Mount Vernon connections. And Arlington, which today visually looks like a natural extension of the city, really was meant to look that way. George Washington Parke Custis, her father, actually had made it to be a part of the District of Columbia. He saw it as being a museum of all these artifacts that he had of Washington’s and things from Mount Vernon. And people did go up there.

COLE: When was Arlington founded as a cemetery?

PRYOR: June 1864.

COLE: Do you have a Lee comment on that?

PRYOR: Oh, yes. The family was wrenched apart by this. Arlington was occupied the day that Virginia seceded. Lee knew that would happen because it’s got a commanding position overlooking the city. Artillery had just been developed that could reach 4 miles, and the Capitol building is 3.8 miles from Arlington. Lee was an engineer, right? He told his wife: “It’s going to be taken over by one side or the other very quickly.” When the Union Army came, there were some noble attempts by Winfield Scott and others to keep the house from being plundered, but eventually it was plundered. And that was really what radicalized the Lees. They had been right on the fence in their loyalties. Mrs. Lee told her husband she would accept whichever way he went, but her leaning was in favor of the Union, because of her connection with George Washington. A very typical border family. After Arlington was taken over Lee wrote that he would rather see its beautiful hill sunk than to have it in such hands.

COLE: Lee was offered command of the Union Army. Was it on the porch of Blair House?

PRYOR: It was at Blair House. We know it was Francis Preston Blair who made the offer. Lee turned it down on the spot. I talk about that in my book. We should not underestimate the power of one person’s decision, especially in a democracy, in a free society, and that whatever you think of that decision, there’s no question that it affected American history. We don’t know exactly how.

COLE: Right.

PRYOR: We don’t know what would have happened had Lee accepted, or had not led the Virginia forces, but we know instinctively something would have been different. So it’s a very powerful moment. I have an image of him at Arlington pacing and praying for days, not knowing what to do because it was such a wrenching decision. Half of his family fought for the North. His sister never spoke to him again. His nephews were on the battlefield against him in several battles, but, you know, this was, again, a classic border-state family story. Some of his cousins were very important officers in the United States Army, Navy.

It’s a terribly sobering story. It doesn’t matter whether you think his decisions—it was several that he had to make at that time—were right or wrong. I don’t think there are very many people who would want to be in the position that he was in at that time.

COLE: He was born at Stratford, right?

PRYOR: Right.

COLE: How long did he live there?

PRYOR: For about three or four years. His father, who had been a genuine Revolutionary War hero— fought with George Washington—but was one of these people who didn’t adapt well to postwar life.

COLE: Was that Light Horse?

PRYOR: Yes, Light Horse Harry, very colorful, endearing man in many ways, but a gambler. He got involved in land speculation, and he got involved in some of the very nasty partisan politics of the time as well. And he lost the family’s money. He was in debtors’ prison for a lot of the time when Lee was a little boy. He finally skipped bail and went to the West Indies and abandoned the family when Robert was about six. So, Robert didn’t really know his father very well. His father was gone, his father was in prison for a lot of the time. I figured out that between the time he was born and the time Light Horse Harry left, he’d only spent about thirty-four months in his father’s company. Most of that had been when he was under two.

The family moved to Alexandria, and they had a safety net in the fact that they had a huge network of relatives there, many of whom were very important people in the United States government, and the local government, and who helped keep them afloat. Lee had a remarkable mother, not a very cheery mother from what I can tell, but she really raised those kids well. They all had this very lovely touch, lots of personality, and rather a fine way of doing things. And they lived really in poverty. His mother talks about Lee and one of his brothers having to share a chicken back for dinner. This is contrary to the sense of him as an aristocrat, you know.

COLE: How did you get onto Lee?

PRYOR: Long ago, when I’d been working for the National Park Service, I was doing some work up at Arlington, and for that restoration I was allowed to look at a number of papers that were still in the Lee family and that had not been published and were really not available to other researchers. And there were all sorts of personal letters Lee had written. So, this was kind of the Comstock Lode, as it were, of Lee material.

I had not known very much about Robert E. Lee except the basic symbolic story. And I was riveted by these letters because they’re very open. They’re very unselfconscious, and they show a person who’s far more complex, has far more dimensions and is far more problematical than the “simple Christian gentleman,” which is how he’s always been portrayed. He’s a wonderful letter-writer, and so the letters are very good company, very entertaining—witty, funny, lusty. These aren’t words we normally associate with Robert E. Lee.

And so I was very intrigued by them, but the Lee family didn’t want us to use them in anything other than the internal workings of restoring the house. We were doing a furnishings study at the time. When I came back from overseas the last time, by chance I found out that the Lees would still let me use these papers and that Robert E. Lee’s granddaughter, who had been reluctant to let them be used, had died, and the rest of the family didn’t have the same reservations.

That gave me the bug again, and I thought, “Oh, I’m going to do something with this!” I was thinking of writing a series of articles, and also finding out what else was out there that hadn’t been used, because I’m a big believer in leaving no stone unturned. Because of this tendency toward “retread” history, people often don’t go out and actually find what primary documents are available. I found, in addition to this original cache of papers, hundreds of letters that had not ever been used and a lot of courthouse records that turned out to be incredibly important in piecing together Lee’s relationship to slavery. I also found a whole cache of letters from Stonewall Jackson that had not been used as far as I can tell.

While I was in the process of putting this all together, another paper stash was found in a bank vault in Alexandria, put there by the Lee family. I had not thought I would get to use that, but I swallowed hard and called up Lee’s great-great-grandson and asked him—and he said yes, I could use them! So, I was the first historian to use those letters as well.

COLE: Which bank was it?

PRYOR: The Burke & Herbert Bank & Trust Company.

COLE: Which is a very old --

PRYOR: Yeah, it had been there since 1852. It had been the Lees’ bank, and the trunks had been left there by his eldest daughter. So, there were these two big steamer trunks full of papers.

COLE: When was the last time they’d been opened?

PRYOR: In 1917 when Lee’s daughter, Mary Custis Lee, put them there. Because she died the following year. There was some vague family memory that they were there, which was how Rob deButts, Lee’s great-great-grandson, thought to call up Burke & Herbert and ask if there was any family material. They found 6,200 documents in these trunks, remarkable things: seventeenth-century documents, which are hard to come by, many from the Custis family; wonderful slave records, which are also rare; an entire dissertation is waiting to be written about Lee’s mother-in-law, who was quite a remarkable woman, and her early anti-slavery activities in northern Virginia, which is, considering her place and time and the fact that she was a woman, astonishing. All of those letters are there. Loads of letters from Lee himself, his jottings after the war, which are quite powerful--and disturbing, actually. He was not a very happy person at that time. In one corner of one of the trunks, we found, wrapped up in tissue paper, stars, his general’s stars, which had been taken from his coat at Appomattox. They all had to take off their insignia after the surrender. And that was very powerful. We had the jacket; the jacket, I believe, was in the Museum of the Confederacy, but the stars were gone. And here they were.

COLE: So where are the stars now?

PRYOR: At the Virginia Historical Society. They’re on display right now.

COLE: How did the letters influence the way you wrote the book?

Pryor: Lee’s personal letters are like a window into the soul of a very private person. I wanted people to have an opportunity to see this vulnerable and challenging side of Lee and to experience the wit and beauty of his writing.

I also wanted readers to understand the process of looking at a document and letting it lead you to surprising places. That’s why I open each chapter with the full text of a letter (or letters) and then follow it with an essay about what the document tells us. I used as my model the way art historians illuminate the hidden mysteries of a masterwork. An untutored viewer sees a picture, has an emotional and visual first reaction to it, identifies its shapes or images. But when an expert points out the factors that influenced the artist, how she or he mixed the paint and chose the colors, where the subject was found and what is behind the iconography, the painting becomes something more than it was. Interpreting Lee’s letters for the reader would give them context and heighten their value.

COLE: How do you think your biography is going to change or reinterpret Lee?

PRYOR: Well, I like to think it amplifies him. Those people who are really wedded to a symbolic Lee might find these things rather disturbing because they think I’m trying to debunk a hero. But I don’t think that that is what I’ve done. As you approach him as a human being, you begin to understand that he went through many of the same vicissitudes of life as the rest of us and was put into difficult situations where there were no good answers and so on. As a result, the leadership qualities that have been revered can actually be admired more.

I like to think that to see a Lee who is depressed and tries to question what his future’s going to be, who feels that he was a failure in his career, is to better understand him. He’s witty. He likes to be a flirt. He writes very bawdy letters to his girlfriends, and he’s crazy about his children. He had seven kids, and he’s a wonderful and very concerned father. There are these rich components to his personality—as well as the doubts and vulnerabilities of any human being.

Those who are used to the rather austere stone icon of mythology will be delighted by Lee’s humor—his letters are really funny—his intense emotional reactions, his open sexuality. Some may be troubled by his clear pro-slavery stance, his wavering spirituality, the unevenness of his generalship, and his bitterness after the war.

I found virtually all of my assumptions about Lee were challenged by the documents I read. I think I was most struck by his vulnerability—he really wears his heart on his sleeve in these letters—and by the difficulty he had making decisions. He agonized over many things for years—and often made decisions that had unfortunate outcomes. I am not just speaking of the big decisions that have been controversial for a long time, such as his actions at Gettysburg or his determination to fight for the South, but other, more personal decisions, as well. He begged his mother to let him go to West Point, for example, yet was disenchanted with army life just a year after graduating. He contemplated leaving the service every year for decades. Couldn’t bring himself to do it though. And just before he died, he told a friend that “the great mistake of my life was taking a military education.” This is a terrible statement: Lee is in essence regretting his entire life.

COLE: Fascinating. And thank you for coming. It’s been great to hear about your fine work as a public servant and also your scholarship.