If you want your child to be a writer, go bankrupt.

The evidence confirms it. Failing that, at least suffer a severe financial reversal, obliging your son or daughter to endure the social opprobrium of changed schools and dropped friendships. Let him know the shame of fallen status, that he might grow ever more attuned to the minutest of slights, real or imagined. Careful scrutiny of his fellows will likely become a habit, a good sense of humor his first line of defense. Imagination will be his refuge. If you want your child to be a writer, do all this, and you may yet join an impecunious fraternity of writers’ parents that includes John Shakespeare, John Joyce, John Clemens, John Dickens, John Ernst Steinbeck, and Kurt Vonnegut, Sr. (Apparently, you might also want to consider changing your name to John.) Not convinced? Throw in Jorge Guillermo Borges Haslam, Edward Fitzgerald, and Richard Thomas Hammett, too.

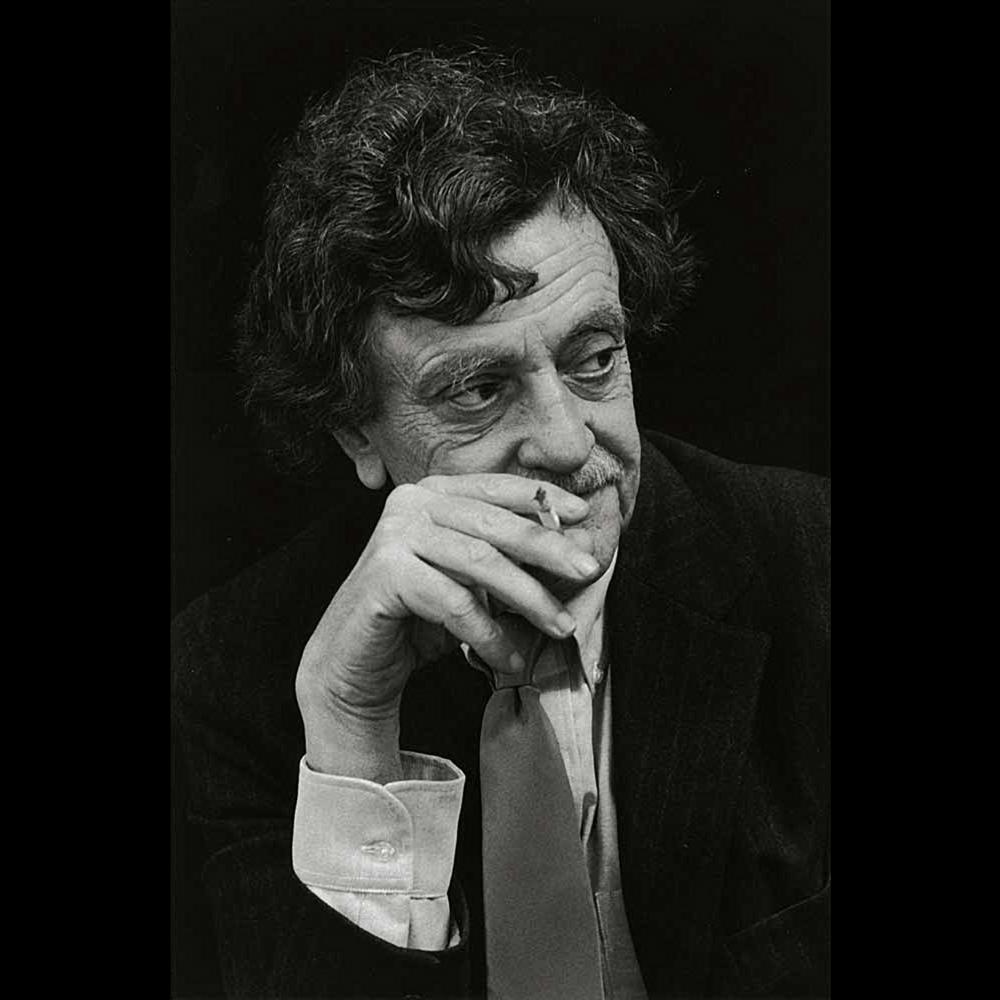

There are great writers whose fathers did not go bust, of course. There are probably also politicians who got enough love as children. Just not many. The late Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., whose most productive decade has just entered the Library of America pantheon with the publication of Novels & Stories 1963–1973, is no less classic a case than the rest.

Born into a prosperous German-American family in 1922 Indianapolis, the son and grandson of architects, his mother a privileged beer heiress soon unstrung by the Depression, Vonnegut was rudely yanked out of private school as the thirties began. “A wise use of resources,” he once ruefully called this step down in the world, still smarting in an interview quoted in Charles J. Shields’s fine, undeluded new Vonnegut biography, And So It Goes.

The hijacking of Vonnegut’s early education embarrassed him not just at the time but down the road, when his career would bring him into contact with writers more well-read than he was. “Who’s Keats?,” he once innocently asked of his writing students at the University of Iowa, and then, mortified at their laughter, fled the room. Two years later, a “Who’s Keats?” banner hung above his thronged, adoring going-away party.

Vonnegut may not have read his Keats, but he found his way early to the models he’d need most: the black humorists Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, and H. L. Mencken. Together they form a too often unacknowledged tradition in our letters, that of the Great American Dyspeptic. (Later, Hunter S. Thompson would join their raffish parade.) If he’s lucky, a reader finds them in adolescence, perhaps first as a suspiciously recurrent presence in Bartlett’s Quotations or other bathroom books. Of them, only Twain was a novelist, and therefore the only one likely to stray onto a school syllabus. Twain has also become the one most strongly identified over the years with Vonnegut, and the one likeliest to wind up alongside him on the business end of some bluestocking’s library or curriculum challenges.

All that dubious glory lay far in the future when Vonnegut first embarked on the genre fiction career that ultimately led to Library of America’s first volume of his writing. That nonprofit publisher has collected four consecutive midcareer Vonnegut novels and a miscellany of incidental writing into its customary handsome volume. Hemmed into its 1963–73 rubric, the book includes only a couple of his short stories, preferring to take Vonnegut from 1963’s Cat’s Cradle, perhaps the purest distillation of his novel-length genre work; through the pointed social satire of God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; past his breakthrough, Slaughterhouse-Five; to 1973’s Breakfast of Champions, which Vonnegut described as his “fiftieth-birthday present to myself . . . as though I am crossing the spine of a roof—having ascended one slope.”

The downhill slope was gentler, but no breeze. The collection forms a fitting tribute to a beloved novelist who peaked late but fast. One year Vonnegut was still writing paperback originals for not much money. The next he was opining darkly on television about the moon landing with Walter Cronkite and Gloria Steinem. The difference was Slaughterhouse-Five, a book with, depending how you count them, at least two titles and two plots, and without which his other novels might, incredibly, not be in print from anyone, let alone the Library of America.

Vonnegut had been trying to shape the material that became Slaughterhouse-Five for twenty years. Rare for writers—rare for anybody—this most formative experience may have befallen him not as a child, but in young manhood. As a World War II POW, he had narrowly escaped the Allied firebombing of Dresden in an underground slaughterhouse. He emerged the next morning to find the whole city transformed into an abattoir, as if his hole had somehow expanded overnight to swallow what was left of the world. The experience, naturally, haunted him, not least because he must have suspected he had found, early on, by far his most important material.

After mustering out of the army, Vonnegut knocked around a bit, newspapering in Chicago and then flacking for General Electric. Always, he was writing. The arc of Vonnegut’s eventual career proceeds steadily from escapist yet thoughtful science fiction to fragmentary personal history. It’s only at the midpoint, Slaughterhouse-Five, that these two axes, the outlandish and the autobiographical, almost perfectly cross. The novel combines stroboscopic flashbacks to Vonnegut’s war experiences with the science-fiction overlay of a character called Billy Pilgrim who has become, in this seemingly plainspoken writer’s lovely formulation, “unstuck in time.”

Slaughterhouse-Five became a counterculture sensation, joining Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and anticipating his fellow Cornellian Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow in their time-scrambled use of the same “good war” to indict the absurdity of any war at all. Lost amid the eminently deserved praise heaped over the years on Slaughterhouse-Five has been Vonnegut’s only other novel-length treatment of the war, the vastly underratedMother Night. Preceding Slaughterhouse-Five by seven years, Mother Night takes the form of a condemned man’s suicide note, the long jailhouse affidavit of an American spy who rose through the ranks of the Third Reich to become Nazi Germany’s star radio apologist.

This tightly plotted and structured book lacks most of its successor’s capering narrative pyrotechnics, concentrating instead on the story of a pathologically rationalizing man’s divestment, one by one, of all his cherished alibis. At the end, bereft of his sweetly loving marriage, his sense of mission as the deepest of deep-cover moles, he stands exposed as the quintessential hypocrite, the Gorgon who can no longer hide from his own reflection. It’s a mordantly thrilling novel, one whose potential eclipse behind the four newly enshrined by Library of America would be an outright shame.

At least two indelible images linger from Mother Night, no matter how long ago a reader thinks he has finished with it. The first is of antihero Howard Campbell’s marital bedroom, which consists of wall-to-wall mattresses where the floor should go. It’s his sanctuary, where he and his wife ride out most of the war in blissful, oblivious devotion. Under any other circumstances, it would be a deeply romantic grace note, and even here we barely begrudge Campbell his fleeting happiness. But in the middle of Nazi Germany, it doubles as a metaphor for the most amoral disengagement.

Later, crossing Manhattan on foot, Campbell experiences a moment of such utter, vertiginous directionlessness that no will or obligation can impel him so much as an inch from the spot. This image of alienation reads almost like something out of Camus. Taken together, these two passages, as visual as any of the doodles that festoon his later writing, distinguish Vonnegut as anything but a strictly comic writer. Each in its way indicts Campbell, and by extension the reader, for a million tiny refusals to involve ourselves in the world around us.

Yet no one book defines a writer—especially a dyspeptic writer—as much as his style. Slaughterhouse-Five and Mother Night may surpass Vonnegut’s other books, as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn all but dwarfs the rest of Twain, but it’s the timbre of an author’s idling voice that we ultimately know him by. Bierce’s ferocious, hypodermic sting, Mencken’s fulminating mock-heroic bombast: These are their fingerprints. It may be worth a few late words here to try to tissue-type what makes a Vonnegut sentence or paragraph unmistakably his alone.

For one thing, of course, a Vonnegut sentence sometimes is a Vonnegut paragraph. Vonnegut didn’t let his nights pasting up the Cornell Daily Sun torpedo a semi-promising academic career without first learning a thing or two about the benefits of shrewdly apportioned white space. His most frequent use of it, the four-word koan “And so it goes” warrants attention on a couple of fronts. Superficially, it’s an affront to every grammar rulebook that ever misinformed impressionable minds about how not to begin a sentence. Less conspicuously, though, it also scans as poetry—iambic dimeter, to be finicky about it, with an internal rhyme thrown in for lagniappe.

Vonnegut’s poetic rhythms serve as a clue to another cornerstone of his style: It’s written for the ear, and meant to be heard. The very first sentence of the new collection, “Call me Jonah,” from Cat’s Cradle, is an imperative, as is the first paragraph of the second chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five, which introduces the whole Billy Pilgrim thread of the story with the single word “Listen.” At least one chapter of Breakfast of Champions begins with the same word, and it recurs with incantatory frequency throughout the Vonnegut corpus. Like any command, it implies both the first and second person, the two most direct spoken voices possible. Vonnegut is talking straight to us, one thing that’s helped endear him to generations of young readers. He also confirms their earliest suspicions that they’re being regularly lied to.

Indispensable to Vonnegut’s humane comedy is this informal sense of reader rapport. The first sentence of Slaughterhouse-Five uses the phrase “more or less,” the second, “pretty much.” Before the paragraph is out, we’ll see “And so on.” Precision matters less to Vonnegut than commiseration, the feeling that we’re all in this together and nobody finishes on top, and therefore that sweating every last adverb may not really be for him.

This isn’t laziness. No lazy man spends the two decades on a novel that Vonnegut lavished on Slaughterhouse-Five. It’s the modesty of a man underpraised for his early books and relatively overpraised for the late ones, who knew he was playing with house money from the day he got out of Dresden alive.

Vonnegut would probably be tickled to take his place on the shelf alongside idols such as Bierce—new to the Library of America catalog in 2011—Twain, and Mencken. Not long before Vonnegut’s death in 2007, according to Shields, “he wanted assurance that his works would occupy a permanent, honorable place on bookshelves and in libraries.”

In light of Library of America’s founding pledge never to drop a volume from its backlist, that place is now secure. Yet another fine writer who succeeded out of a household that failed, Vonnegut deflected doubt and self-doubt alike with astringent jokes that stung like poison. Born into prosperity, raised in austerity, redeemed by posterity, the last laugh is finally his.