“There are no dangerous thoughts; thinking itself is a dangerous activity.” Hannah Arendt

Fifty years ago, on October 28, 1964, a televised conversation between the German-Jewish political theorist, Hannah Arendt, and the well-known German journalist, Günter Gaus, was broadcast in West Germany. Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, her controversial analysis of the Jerusalem trial of Adolf Eichmann, had just been published in German in the Federal Republic and Gaus used the occasion to generate a “portrait of Hannah Arendt.” The interview ranged across a wide field of topics, including the difference between philosophy and politics, the situation in Germany before and after the war, the state of Israel, and even Arendt’s personal experiences as a detainee in Germany and France during the Second World War.

Already a cause célèbre in the United States, the book had brought Arendt lavish praise and no small amount of damnation. What Gaus especially wanted to know was what Arendt thought about criticism levied against her by Jews angered by her portrait of Eichmann and her comments about Jewish leaders and other Jewish victims of the Holocaust. “Above all,” said Gaus, “people were offended by the question you raised of the extent to which Jews are to blame for their passive acceptance of the German mass murders, or to what extent the collaboration of certain Jewish councils almost constitutes a kind of guilt of their own.”

Gaus acknowledged that Arendt had already addressed these critics, by saying their comments were, in some cases, based on a misunderstanding and, in others, part of a political campaign against her, but he had already crossed a contested border. Without hesitation, Arendt corrected Gaus:

First of all, I must, in all friendliness, state that you yourself have become a victim of this campaign. Nowhere in my book did I reproach the Jewish people with nonresistance. Someone else did that in the Eichmann trial, namely Mr. Hausner of the Israeli public prosecutor’s office. I called such questions directed to the witnesses in Jerusalem both foolish and cruel.

True, Gaus admitted. He had read the book and agreed that Arendt had not made that point exactly. But, he continued, some criticism had been levied against her because of “the tone in which many passages are written.”

“Well,” Arendt replied, “that is another matter. . . . That the tone of voice is predominantly ironic is completely true.”

What did she mean by ironic? “If people think that one can only write about these things in a solemn tone of voice. . . . Look, there are people who take it amiss—and I can understand that in a sense—that, for instance, I can still laugh. But I was really of the opinion that Eichmann was a buffoon.”

To convey the shock she experienced when, contrary to her own expectations, Eichmann “in the flesh” appeared to be more a clown than a monster, Arendt countered with a reverse shock, adopting a sardonic, unsentimental voice to unmask what she later termed “the banality of evil.” It could be read as her way of diminishing the self-aggrandizement of the architects of the Final Solution to middling size. The trouble was she used this voice rather undiplomatically to describe not only Eichmann’s actions but also the complicity of others, including some members of the Jewish community she judged harshly for cooperating with Nazis.

“When people reproach me with accusing the Jewish people, that is a malignant lie and propaganda and nothing else. The tone of voice, however, is an objection against me personally. And I cannot do anything about that.”

“You are prepared to bear that?” asked Gaus. “Yes, willingly,” Arendt claimed.

What she had not anticipated was how unprepared many readers were to take on this new shock of the “banality of evil” on top of the horrifying accounts of Jewish suffering conveyed at the trial.

In fact, “bearing the burden of the past,” thinking about the past in its morally perplexing and disconcerting entirety, was the focus of Arendt’s writing, from her earliest essays to her last. And in no case did this burden-bearing affect her more personally than when she published Eichmann in Jerusalem. When she returned from a European trip taken for a needed rest soon after the book’s release, she found stacks of letters waiting for her. Some correspondents praised the bravery of her truth-telling, but the lion’s share found her book detestable. A few included death threats.

Was her refusal to concede that her “tone” had anything to do with the hostility the book generated merely a matter of sheer stubbornness? Or was the ironic tone itself emblematic of Arendt’s ideas about the danger implicit in thinking and the burden of responsibility that lay at the heart of judgment?

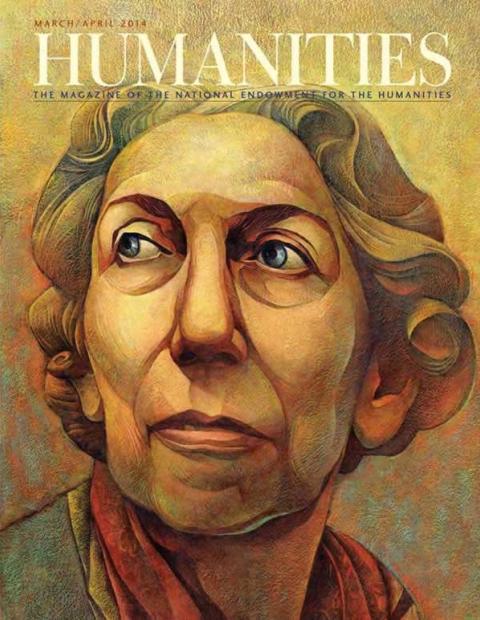

Hannah Arendt defies easy categorization. She was a brilliant political philosopher, who refused to call herself a philosopher. She was a woman who never considered her sex to be an obstacle in her life. And she was a Jew who was called anti-Semitic for her controversial portrait of Adolf Eichmann as a “thoughtless,” “terrifyingly normal” person.

Born in 1906 into a German-Jewish family, she studied philosophy in the 1920s with Martin Heidegger in Marburg and continued her research with Karl Jaspers in Heidelberg, writing a doctoral dissertation on the concept of love in the writings of St. Augustine. But it was her personal experience of the rise of Nazism in Germany combined with her years of statelessness, which turned her away from philosophy to politics.

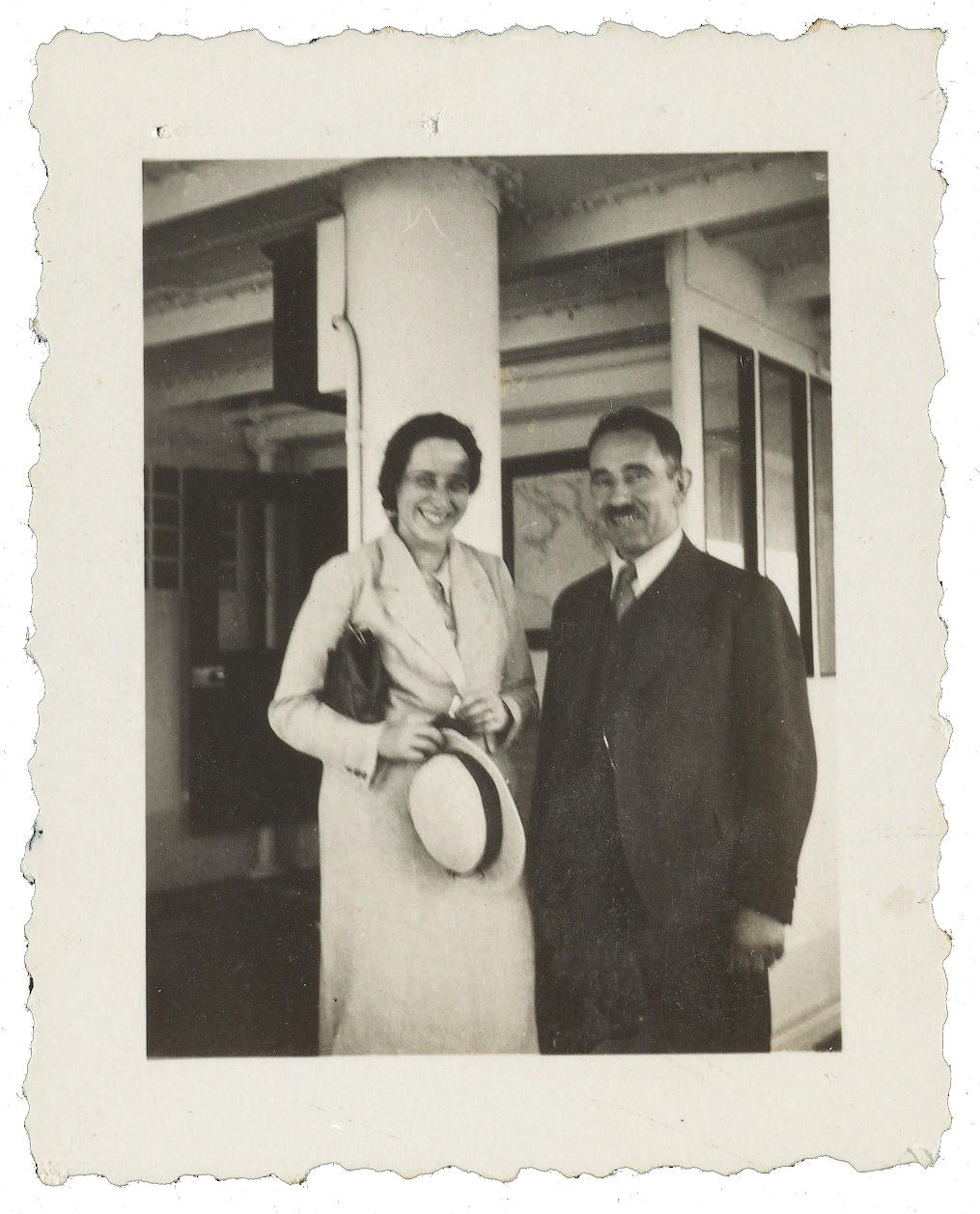

While still living in Germany, she clandestinely collected information on Nazi propaganda for a Zionist organization, which landed her in prison for a week until a German police officer, whom she claimed to have befriended, released her. Exiled in Paris in 1933, she worked for Youth Aliyah, bringing shiploads of stateless Jewish children and young people to Palestine in 1935. In 1940, she was arrested and detained in the Vélodrome d’Hiver in Paris, along with thousands of other Jewish women and children, and sent to Gurs, a concentration camp in southwest France. Escaping, she reached Montaubon in unoccupied France, first by hitchhiking and then continuing on foot. By chance, she reunited there with her husband, Heinrich Blücher, who had been evacuated from a different internment camp. Well known enough to be given a place on the American journalist Varian Fry’s list of famous Jews to be saved, Arendt boarded a ship in 1941 along with her husband and sailed from Lisbon to America, becoming one of the last Jews to get out of occupied France.

When she became a U.S. citizen in 1950, her statelessness ended. But her interest in the subject never waned. What conditions enabled some people to deny others the most basic right to exist and even target them for extermination? This question animated her monumental work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, a project she had begun in the 1930s with her investigation of the history of anti-Semitism. And it was a question she widened into an exploration of the conditions that enabled people to commit crimes against humanity, which took her to Jerusalem for the Eichmann trial.

In 1960, the Israelis kidnapped the notorious Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and brought him to Jerusalem to stand trial for his part in the Final Solution. Eichmann had been responsible for keeping the process of deporting Jews running smoothly, first organizing them for removal to deportation centers and ultimately consigning them to the killing centers in Eastern Europe. When word of his capture and forthcoming trial reached Arendt, she immediately contacted William Shawn, editor of the New Yorker, and offered herself as a “reporter at large.” She wanted “to see these people in the flesh.” Shawn jumped at the opportunity.

By then, Arendt was well known. Her 1951 publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism had positioned her as an early and innovative interpreter of the total terror inaugurated by this new form of government. Totalitarian government had fabricated what she called “the crisis of our century”—the state’s manufacturing of a “world of the dying, in which men are taught they are superfluous through a way of life in which punishment is meted out without connection with crime, in which exploitation is practiced without profit, and where work is performed without product . . . a place where senselessness is produced daily anew.”

Arendt urged reading the record of the totalitarianism of both the Nazi and Stalinregimes as a cautionary tale about the forces in the “subterranean stream of Western history,” which contributed to the development of what she then called the “truly radical nature of Evil.” The creation of death camps was an “event that should never have been allowed to happen.” More chillingly, she claimed this “event” was neither the product of circumstances beyond human control, nor the inexorable result of prior conditions. Rather, it happened because of the failure of ordinary people to stop it. How did she account for this failure?

During the course of attending Eichmann’s trial, and the more she read in the voluminous transcripts and other trial documents, including Eichmann’s own writing, Arendt hit upon an insight she continued to pursue in later work, including her posthumously published book, The Life of the Mind. The insight was this: It was Eichmann’s “thoughtlessness”—the absence of thinking—that enabled him to commit monstrous acts. Eichmann’s thoughtlessness exemplified what she called “the fearsome, word-and thought-defying banality of evil.”

Nothing placed Arendt in the storm center of public opinion more than her essays about the trial first published in February and March 1963 in the New Yorker, which ultimately became Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. The year Eichmann was published, the Anti-Defamation League sent out a circular to rabbis to preach against her on Rosh Hashanah. To this, Arendt responded in a letter to her friend, the author Mary McCarthy, “What a risky business to tell the truth. . . .” With close to 300,000 copies now sold, Eichmann in Jerusalem remains Arendt’s most widely circulated and most vilified “public” work. Why?

A haunting meditation on the near total eclipse of morality under the Third Reich, Eichmann is a provocative, often distressing exercise in thinking. Over Arendt’s “report” hangs the shadow of her complicated judgment of the scope of horrors associated with the Holocaust, whose source she summarized in the phrase “the banality of evil.” Among the more disturbing conclusions she reached were those about Eichmann himself: “Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a ‘monster,’ but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown.” He was not the incarnation of evil, she wrote; he was “thoughtless,” unable to reflect on the fact that what he was doing was wrong. “The longer one listened to him, the more obvious it became that his inability to speak [in anything but clichés] was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else.”

In Origins, Arendt had underscored the importance of ideology to the creation of the Nazi state. Embedded in the elaborate bureaucracy and obfuscating language and legal rules of the Nazi government, ideology served to inure people to the murderous reality of the regime. Eichmann’s testimony revealed to Arendt his amazing capacity to speak only in clichés and stock phrases and an equally astounding incapacity to think. Here was Eichmann “in the flesh,” but what shocked Arendt was how commonplace he was.

Eichmann testified that, in fact, he did know what he was doing and went on at great length describing how good he was at his job. But, for Arendt, knowing and thinking were not the same thing. To know meant to know how to do something—such as how to coordinate transportation. Knowing was separate from stopping to think about the meaning of one’s actions, whether it was wrong to be transporting trainloads of people to their death. To Eichmann, what would have been wrong was any failure to do his job. This was neither blind obedience nor the performance of a mere cog in a wheel. It was the carefully planned and skillfully executed strategy of a “joiner,” one of those “job holders and good family men.”

As if he were only a “leaf in the whirlwind of time,” Eichmann appeared in Arendt’s narrative as someone unable to reflect on the difference between sending people to their deaths and doing his job. Yet the real trouble, she wrote, wasn’t Eichmann; it was how many others were like him—terrifyingly normal, banal perpetrators of evil acts. What had happened, Arendt wondered, to make so many people thoughtless? “From the accumulated evidence one can only conclude that conscience as such had apparently got lost in Germany.”

But not only in Germany. While never equating their actions with those of the Nazis, Arendt nonetheless judged members of the Judenräte (Jewish councils of community leaders organized by the Germans in occupied Europe) unfavorably for cooperating with the Nazis by giving them lists of Jews to deport. In one of the most frequently quoted passages from the book, she even assigned a measure of responsibility to some of the victims. “Wherever Jews lived, there were recognized Jewish leaders, and this leadership, almost without exception, cooperated in one way or another, for one reason or another, with the Nazis. The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized or leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and a half and six million people.” And to a Jew, she wrote, “this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter in the whole dark story.” It was passages such as these that Gaus had in mind when he questioned Arendt about her tone.

Arendt claimed to be justified in “dwelling” on this chapter in her book because the prosecution had brought forth the testimony of witnesses who alluded to the role of the Jewish councils, which had already been made known, she wrote, in “all its pathetic and sordid detail by Raul Hilberg ” in his book, The Destruction of the European Jews. More than this, she thought it provided deeper insight into the “totality of moral collapse the Nazis caused in respectable European society.”

Yet if the particular way she exposed this “dark chapter” is uncomfortable to read even today, the impact of her words crossed the border from uncomfortable to outrageous in the early 1960s, when the Holocaust and Jewish suffering had yet to be discussed as fully and publicly as in the Jerusalem trial, much less made into a subject of study. What was Arendt thinking when she wrote that “justice insists on the importance of Adolf Eichmann. . . . On trial are his deeds, not the suffering of the Jews, not the German people and mankind, not even anti-Semitism and racism”? She was thinking about thinking.

In the introduction to The Life of the Mind, Arendt offered this account of the generation of her controversial and still frequently misunderstood concept of “the banality of evil”:

In my report of [the Eichmann trial] I spoke of “the banality of evil.” Behind that phrase . . . I was dimly aware of the fact that it went counter to our tradition of thought—literary, theological, or philosophic—about the phenomenon of evil. . . . However, what I was confronted with was utterly different and still undeniably factual. I was struck by the manifest shallowness in the doer that made it impossible to trace the uncontestable evil of his deeds to any deeper level of roots or motives. The deeds were monstrous, but the doer—at least the very effective one now on trial—was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous. . . . Might the problem of good and evil, our faculty of telling right from wrong, be connected with our faculty of thought? . . . Could the activity of thinking as such, the habit of examining whatever happens to come to pass or to attract attention, regardless of results and specific content, could this activity be among the conditions that make men abstain from evildoing or even actually “condition” them against it?

But, Arendt insisted, thinking’s ability to condition people against evildoing did not mean “that thinking would ever be able to produce the good deed as its result, as though ‘virtue could be taught and learned’—only habits and customs can be taught, and we know only too well the alarming speed with which they are unlearned and forgotten when new circumstances demand a change in manners and patterns of behavior.” What cold comfort, then, this thinking business seemed to be, offering no guarantee that evil will be avoided and good will prevail.

To Arendt, thinking remained the only possible bulwark against the dangerous certainty of “hold[ing] fast to whatever the prescribed rules of conduct may be at a given time in a given society.” In a society where the rules against murder have been inverted, the dangerous questioning of those rules enabled some people to refuse to follow them. The trouble was, Arendt observed in Eichmann in Jerusalem, Eichmann had been surrounded by “an aura of systematic mendacity that had constituted the general, and generally accepted, atmosphere of the Third Reich.” And under such conditions, only those who thought for themselves were able to judge the wrongs of such a regime. Who were they?

Arendt recounted several stories from the Jerusalem trial to illuminate the lives of the ordinary people who demonstrated the capacity to think that Eichmann so manifestly lacked. One such person was Anton Schmid. Schmid had been in charge of a German patrol in Lithuania and his job was to collect stray soldiers and return them to their units. In the course of his regular duties, he befriended members of the Jewish underground and began supplying forged papers and trucks in which Jews escaped. For over a year he persisted, until he was arrested and executed in 1942. “How utterly different everything would be today in this courtroom, in Germany, in all of Europe, and perhaps in all the countries of the world, if only more such stories could be told.” Arendt concluded that Schmid’s story made visible something both morally and practically useful: “under conditions of terror most people will comply, but some people will not, just as the lesson of the countries to which the Final Solution was proposed is that ‘it could happen’ almost anywhere but it did not happen everywhere. Humanly speaking, no more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a fit place for human habitation.”

Some scholars have criticized Arendt for portraying the actions of some German dissenters in a better light than Jews who resisted. But, like it or not, Arendt’s strategy is consistent with her description of the reversal that critical thinking effects. Arendt wrote against the grain of well-settled assumptions about an absolute distinction between victim and perpetrator. She worried such a distinction was based on certain racialized definitions, characterizing Jews as perpetual victims and Germans as culturally determined aggressors. Transgressing that boundary, Arendt wrote in the interest of salvaging human freedom and the burdensome responsibility it places on everyone’s shoulders. “Personal or moral responsibility is everybody’s business.”

Arendt had removed the guarantee of absolute innocence and automatic guilt from the question of moral responsibility. What did she put in its place? The capacity to exercise an “independent human faculty, unsupported by law and public opinion, that judges in full spontaneity every deed and intent anew whenever the occasion arises.” And who evidenced this capacity? They were not distinguished by any superior intelligence or sophistication in moral matters but “dared to judge by themselves.” Deciding that conformity would leave them unable to “live with themselves,” sometimes they even chose to die rather than become complicit. “The dividing line between those who want to think and therefore have to judge by themselves, and those who do not, strikes across all social and cultural or educational differences.”

Nonetheless, Arendt’s tone made it seem as if she knew she would have acted more valiantly than those who cooperated with the Nazis. Outraged by her moral judgment of Jewish leaders, many asked, Who is she to judge those who were forced to make difficult decisions and, in the interests of saving the many, sacrificed the few? Arendt answered this question in a 1964 essay entitled “Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship”: “Since this question of judging without being present is usually coupled by the accusation of arrogance, who has ever maintained that by judging a wrong I presuppose that I myself would be incapable of committing it?”

The wisdom of Arendt’s tone and conclusions in Eichmannn in Jerusalem continue to be debated, most recently in response to Margarethe von Trotta’s 2012 film, Hannah Arendt. Yet the significance of what Arendt wrote about the absence of thinking and the problem of evil warrants further consideration, especially in light of the apparent ease with which different groups have become the targets of contemporary genocidal campaigns. As the Croatian novelist Slavenka Drakulić wrote in her book They Would Never Hurt a Fly (titled after a phrase of Arendt’s): “The more you realize that war criminals might be ordinary people, the more afraid you become.”

For Arendt, the capacity to think for one’s self, to reflect and “make up your mind anew” whenever one was “confronted with some difficulty in life” was, in the modern age, no longer the province of “professional thinkers.” It was a faculty every ordinary person must be expected to exercise. No matter how much you agree with her conclusions, reading Eichmann remains an invitation to engage in the dangerous business of thinking.