In two streaked and faded panels, the painted figures, possibly Rama and Sita from the Hindu epic Ramayana, float like ghostly apparitions. The wooden carving, too, shows signs of age, worn smooth in places. Time, sunlight, and weather have done their work.

But even in pristine condition, these Balinese temple doors, which date from 1700–1800, would have had a fragile and evanescent look. Framed in floral tracery, with images of fire above the figures’ heads, the doors are crowned by a porous lintel screen of leaves and blossoms. The spaces above the side panels are open, with a pair of feathery winged lions perched on the window ledges. Another pair of more conventional lions stands guard, benignly, at the base.

The entire piece, on view in the transporting exhibition “Bali: Art, Ritual, Performance” at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, seems light and fanciful, almost vaporous, a vivid dream that might dissolve and vanish at any moment. As such, these hauntingly ephemeral doorways could hardly be a more fitting entry for the show, a prismatic display of carving and textiles, masks and musical instruments, painting and video, and costumes and photographs. Like the Balinese themselves, who cherish the free and fluid passage from everyday life to the sacred, the visible realm (sekala) to the unseen (niskala), the visitor encounters the interwoven beliefs and values, aspirations and absorbing love of natural beauty, the transitory and the indelible that mark the distinctive culture of this fabled Indonesian island.

Temples are central to those ideas, explains curator Natasha Reichle, who spent five years working on this first major exhibition of Balinese arts in a U.S. museum. “There are tens of thousands of them,” she says. They range from towering structures with elaborate depictions of Hindu deities to village temples devoted to various nature gods and modest ancestral shrines. “Whether it’s one of the major rituals that takes place every 210 days (linked to the complex Balinese calendar) or it’s someone putting a little bit of rice on a palm leaf as an offering,” says Reichle, “there’s a constant mediation between the two worlds. The people have an intense involvement with the spiritual on a daily physical level.”That fact extends well beyond specifically sacred practices. Indeed, as Reichle writes in the catalog, “The concept of religion as being separate from traditions or culture is a foreign one.” There are no boundaries between religion and many other traditions in Balinese life. Local rituals, worship rites, and certain agricultural practices are all part of a spiritual continuum, loosely defined by the Sanskrit term agama.

In the show’s first gallery, harvesting knives, rice-sheaf paddles with brightly grinning faces, and willowy doll-like figurines made of woven palm leaves celebrate Dewi Sri, Bali’s rice goddess. Just as the island’s most important agricultural crop is closely linked to spiritual beliefs and rituals, so is the all-important trade that has helped sustain Bali through the centuries. A pair of jaunty statues that depict Dewi Sri’s consort, Rambut Sedana, the god of wealth, are made from Chinese coins. The earliest such coins found on the island date to the ninth-century Chinese Tang Dynasty.

Bali, a diamond-shaped island of two thousand square miles in the Indonesian archipelago, was inhabited as far back as the Paleolithic era. Austronesian speakers migrated from China and Taiwan around 3000 BCE.

The tympanum of a bronze drum (1–200 CE), decorated with a swirling snake-like pattern around a central star, is the oldest object in the show. Music and performance are central to the Balinese worldview and way of life.

Archaeological finds of pottery and other objects confirm that Bali was a port for Chinese and Indian traders as early as the first century CE. Hinduism arrived in the eighth century CE, mingling with beliefs in natural gods and ancestor myths, all of which have gone on entwining to the present day.

That’s apparent in an absorbing video of a contemporary cremation ceremony. These complex and moving rites include sacred water blessings, brilliantly costumed processions, dances to confuse the evil spirits, abundant offerings, and the dramatic burning of animal-form sarcophagi and the temporary wooden towers that house them. The body’s remains are adorned with flowers and floated away on a stream. Fourteen days later, the family makes a pilgrimage to the ocean with still more offerings.

A feverishly detailed painting by the twentieth-century artist I Made Djata captures the immersive character of a village funeral procession. A series of floridly decorated palanquins, used to transport deities in their travels to and from temples, forms another evocative highlight of the show.

Bali scholar David J. Stuart-Fox describes a cosmology, the nawa sanga system, built around a center and eight additional directions, each associated with a color, number, weapon, and power syllable. Add the zenith and nadir, and the number of directions grows to eleven. Balinese belief systems, writes Stuart-Fox, are the “unique result of intellectual and creative contact of the Balinese people with Indian religions over a period of two thousand years.”

Politics and the historical flow of power in Bali are no less complicated. In a landscape dominated by a range of volcanic mountains and deeply fissured ravines, multiple kingdoms rose and fell along territorial lines through the centuries, with nearby Java periodically asserting its might. The Dutch first arrived around 1600, but it wasn’t until the middle of the nineteenth century that their colonial rule was imposed.

A second pair of wooden doors, in the show’s last gallery, supplies a wrenching story of the colonial era. Gorgeously carved between 1800–1900 for a raja’s palace, the doors were rescued by a collector in 1906 after he witnessed the brutal climax of a Dutch military action. In a bloody puputan (ending), an estimated one hundred members of the raja’s palace household, regally dressed in white, walked straight out of the palace into the gunfire of the Dutch. White, used in cremation rites, is the color of purification.

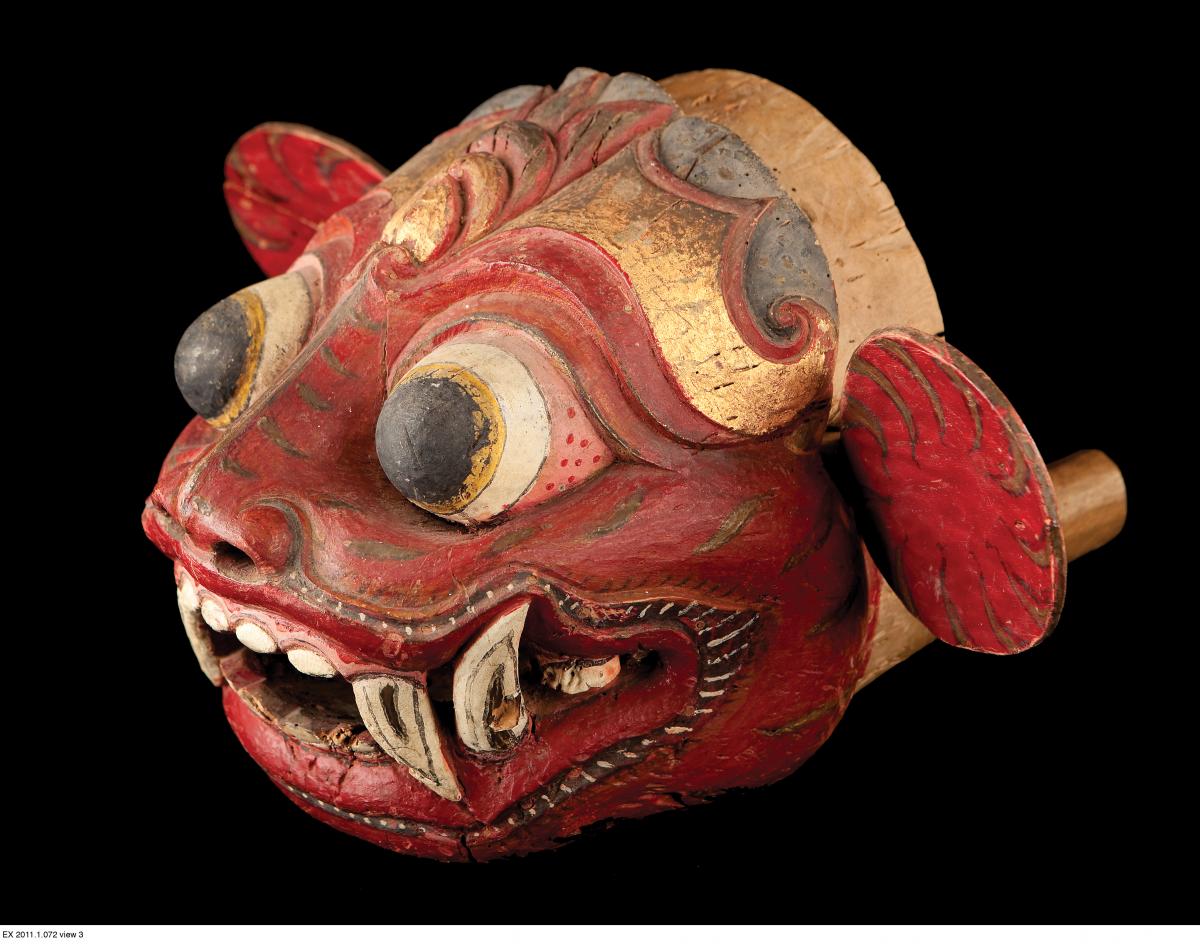

This same gallery covers another chapter in Bali’s dense and fascinating narrative. The “Paradise Collected” section of the show documents the intense interest in Bali that arose in the twentieth century, with such luminaries as H. G. Wells, Charlie Chaplin, and Noel Coward drawn to the island. Everything from shadow puppets to theatrical masks to wooden statues made specifically for the tourist trade, some of which are quite captivating, is on display.

Recognizing that no conventional exhibition could do credit to the important performative aspect of Balinese culture, the Asian Art Museum has mounted a series of live events and demonstrations. The sumptuous Makrokosma Bali, performed four times in May, featured Sekaa Gong Taruna Mekar, a 25-member gamelan orchestra from Tunjuk in Bali. As video screens behind the musicians danced with scenes of village life, images of nature and dreamy abstractions, the musicians conjured up Akasa (space), Bayu (wind), Apah (water), Teja (fire), and Pertiwi (earth). The effects ranged from loud and clangorous to charged yet silent, when the performers bobbed and weaved and thrust their hands up to represent a crackling fire.

At once inventive, eventful, and wistful, Makrokosma Bali brought to mind an ink painting called Goodbye and Good Luck to Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, which appears near the end of the museum show. A 1938 work by I Ketut Ngendon, the painting crowds the wonder and whimsy, the sensuality, and sense of playfulness of Bali into a single frame. As nearly nude villagers gather on the shore to bid farewell to the anthropologist couple in their outrigger canoe, a volcano puffs out the letters that read “Goodbye and Good Luck.” The water ripples in quilted patterns. Trees thick with leaves rise above thatched huts. Enormous blossoms open in the foreground. Why, one can’t help thinking of Mead and Bateson, would anyone choose to leave all this behind?