In 1689, Kangxi, the emperor of China, embarked on a tour to inspect his southern provinces, undertaking a two-thousand-mile journey from Beijing to the cities and towns of the Yangzi Delta and back. Included in the emperor’s retinue were his mother, the dowager empress, as well as imperial wives, children, concubines, bureaucrats, and thousands of soldiers.

As part of the tour, Kangxi climbed to the top of Mount Tai, the “cosmic peak of the East” and a site sacred to all three Chinese religious and philosophical traditions—Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism. For centuries, Chinese emperors had made pilgrimages to Mount Tai to worship earth (at the base) and heaven (at the summit) and affirm the legitimacy of their rule. An emperor only visited when he could provide a glowing account to the cosmos about the state on the empire. In Kangxi’s case, he could report on a new era of stability in the nascent Qing dynasty and increasing prosperity throughout the empire.

Kangxi’s visit to Mount Tai represented more than just the fulfillment of an age-old religious rite. Potent political symbolism was at work at well. As a Manchu, Kangxi was considered an outsider by the Han Chinese over whom he ruled. When the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) began to crumble in the early seventeenth century, the Manchus, who ruled the region to the northeast, began seizing territory. By 1662, the Manchus controlled Beijing, had disposed of claimants to the Ming throne and launched the Qing dynasty that would rule China until 1911. By visiting Mount Tai, the emperor sent a message to his subjects that he intended to rule not as a Manchu conqueror, but as a traditional Chinese monarch.

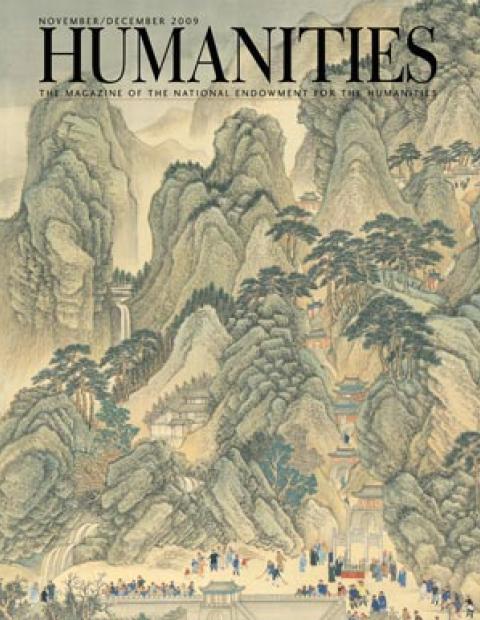

Given the importance of Kangxi’s visit to Mount Tai and of the inspection tour itself, it is not surprising that steps were taken to record it for posterity. Instead of a soaring obelisk or a towering arch, which would be the European choice, the tour was commemorated in a series of twelve handscrolls. The format was perfect for documenting a long journey, as it would allow the viewer to follow the progress of the emperor’s retinue. Each scroll measured twenty-seven inches from bottom to top and forty to eighty-five feet wide. Laid end to end, the scrolls spanned the length of three football fields.

Although primarily intended to document a historic tour, the scrolls also transformed the painting style of the Qing dynasty and christened the Orthodox school as the dominant style. Six decades later, the Qianlong emperor would emulate his grandfather, embarking on his own inspection tour and commissioning his own scrolls, leading to yet another artistic revolution.

The story of the Southern Inspection Tour scrolls, as they are collectively known, begins with the Kangxi emperor. In 1661, at the age of seven, Kangxi ascended the throne following the death of his father from smallpox. At the age of fifteen, with the help of his tutor and his grandmother, the grand dowager empress, he deposed the courtiers who had ruled on his behalf and assumed control of state affairs. The empire he inherited was vast, but politically and ethnically fractured, and Kangxi would devote his reign—which at sixty-one years wasone of the longest in Chinese history—to consolidating Manchu power and promoting national unity, while also showing respect for the traditional Chinese culture of his subjects. His efforts would make him one of the most lauded and respected emperors of China.

For the Qing dynasty to succeed, Kangxi recognized that he needed to harness the resources of the southern provinces, which boasted the agriculturally rich Yangzi Delta and the cosmopolitan cities of Nanjing, Suzhou, and Shaoxing. He also needed to stamp out any last vestiges of Ming loyalty in the region. To bolster support for his rule, Kangxi embarked on a savvy southern strategy, which included enlisting the intelligentsia of the southern provinces to act as his advisers and provide a welcome counterbalance to the Manchu influence at court. The idea for the tours, of which there would ultimately be six, most likely originated with them. The first inspection tour occurred in 1684 on the heels of the suppression of the Three Feudatories Rebellion and was designed as a show of military strength, to discourage any budding rebels.

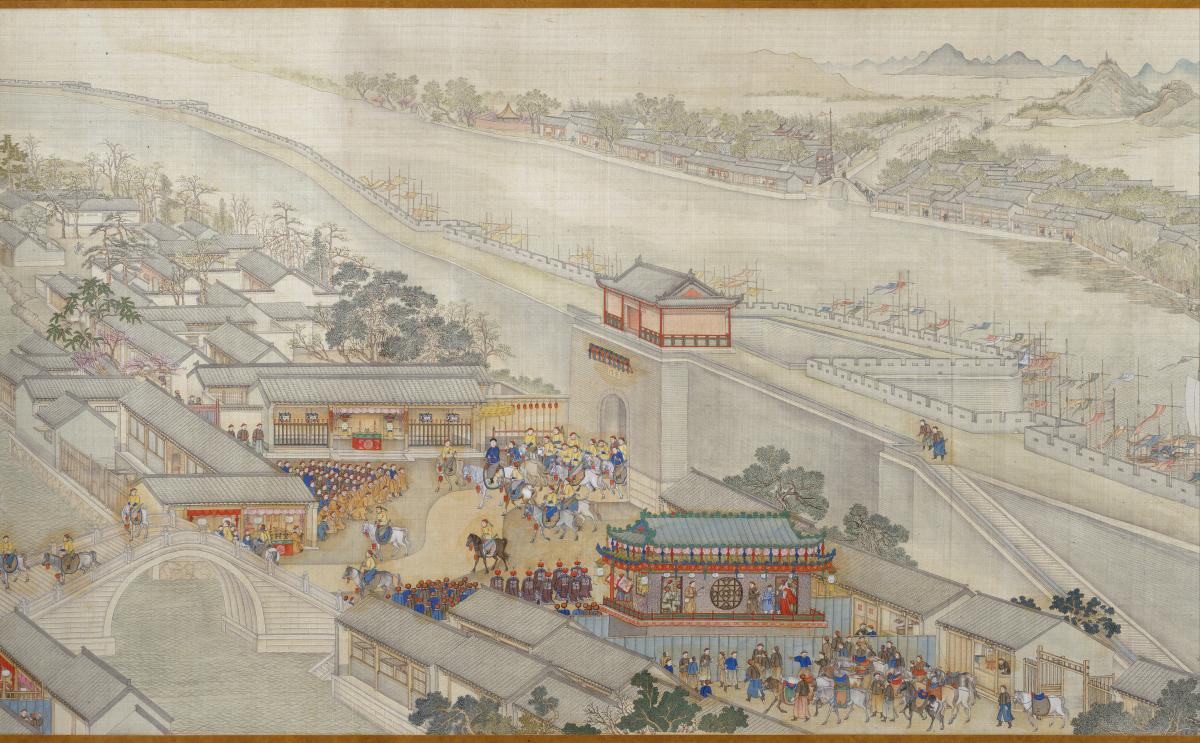

By the time of the second tour in 1689, the political stability of the south allowed for a longer tour (seventy-two days) with more pomp and pageantry. While the tour was an inspection in the sense that Kangxi was surveying his lands, it was also a public relations offensive in that it provided a structured way for the emperor to be among his people. The extensive retinue and elaborate welcoming ceremonies gave the people a taste of the grandeur of court and a glimpse of their ruler. The tour, however, wasn’t entirely imperial theater. Kangxi met with officials and scholars, inspected the Grand Canal and key waterworks, and toured farms and markets. Military troops were reviewed and homage paid to the ancestors at sacred sites, including Mount Tai. Local artisans shared their crafts, showcasing regional skills and indigenous goods. Dancers and singers staged elaborate productions in his honor. For the locals, the arrival of the emperor ushered in tax-free holidays and special sessions for the civil service exam.

We know details of the tours from the imperial diary, tribute poetry, and the paperwork needed to make it all happen. But only one tour—the second one, featuring the journey to Mount Tai—would be chosen by the emperor to be artistically commemorated. The idea of recording the tour for posterity probably originated with a Manchu prince who served as one of Kangxi’s advisers, says Maxwell K. Hearn, the Douglas Dillon Curator of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The prince was a patron of Wang Hui, an artist specializing in long landscape handscrolls, which favored linear storytelling.

Before he began to paint, Wang drafted the scenes on paper and submitted them for approval. Only after the emperor gave his blessing was Wang given the fine silk for his canvas and the minerals to create the paints. Wang used a workshop to produce the twelve scrolls. A team of artists trained in his style were assigned parts of the scrolls based on their strengths in rendering people, landscape, or buildings.

Wang’s style, which became known as the Orthodox school, merged the landscape styles of the Song dynasty (960–1279) with the calligraphic brushwork of the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). It also used a distinctive blue-green palette. The fusion of styles was intended to invoke the grandeur of previous dynasties. "I must use the brush and ink of the Yuan to move the peaks and valleys of the Song, and infuse them with the breath-resonance of the Tang. I will have a work of the Great Synthesis," wrote Wang. Impressed with Wang’s achievement, the emperor bestowed upon him the honorific name “Landscapes Clear and Radiant.”

After they were completed, the scrolls were kept in a storeroom that housed maps (considered to be top secret), important state documents, and imperial portraits. Although the scrolls were never intended for public view, their influence on Qing art was profound. “The fact that Wang was chosen for the task made the Orthodox style of painting the dominant style at court,” says Hearn. The style would be used by Wang in commissions for other patrons and imitated by other artists throughout the empire. For the duration of the Qing dynasty, artists would reference and wrestle with Wang’s style.

Six decades later, Kangxi’s inspection tours and scrolls would be emulated by his grandson Qianlong, who ruled from 1736 to 1795. When Qianlong took the throne at the age of twenty-five, he inherited a prosperous country with a vibrant economy. Not content with the status quo, he launched ambitious military campaigns in the west to extend Qing control over Tibet and Central Asia, adding another 600,000 square miles to the empire. Qianlong also secured China’s borders against the Turks and Mongols and reasserted control over the southern provinces, the same region that had bedeviled his grandfather.

While Qianlong was proud of his hard-fought military victories, he would cite his six southern inspection tours, conducted between 1751 and 1784, as one of his most important achievements. These lavishly outfitted tours sought less to unify than to display the power of the emperor. “By the time the Qianlong emperor came to the throne, the empire was at peace and there was less of a political reason for the emperor to go on tour,” said Hearn. Along with the customary tours of waterworks and conversations with local officials, there were shows of hunting, horsemanship, and marksmanship by his bannermen.

Qianlong also followed Kangxi’s example when he commissioned the creation of twelve scrolls to commemorate his first tour. The scrolls were begun in 1764, thirteen years after the tour, and completed six years later, just in time to be presented to the emperor for his sixtieth birthday. They were primarily the work of one artist, court painter Xu Yang.

While there is some familial emulation at work, the emperor’s ego should not be discounted. “Qianlong was eager to promote himself. He used art far more effectively and extensively to create an image of himself than Kangxi,” says Hearn. Numerous paintings were created depicting him as a warrior, a family man, a Confucian scholar, and a Daoist priest. “Clearly for him, the Southern Inspection Tour scrolls were a way to duplicate what his grandfather had done while also a form of self-aggrandizement,” says Hearn.

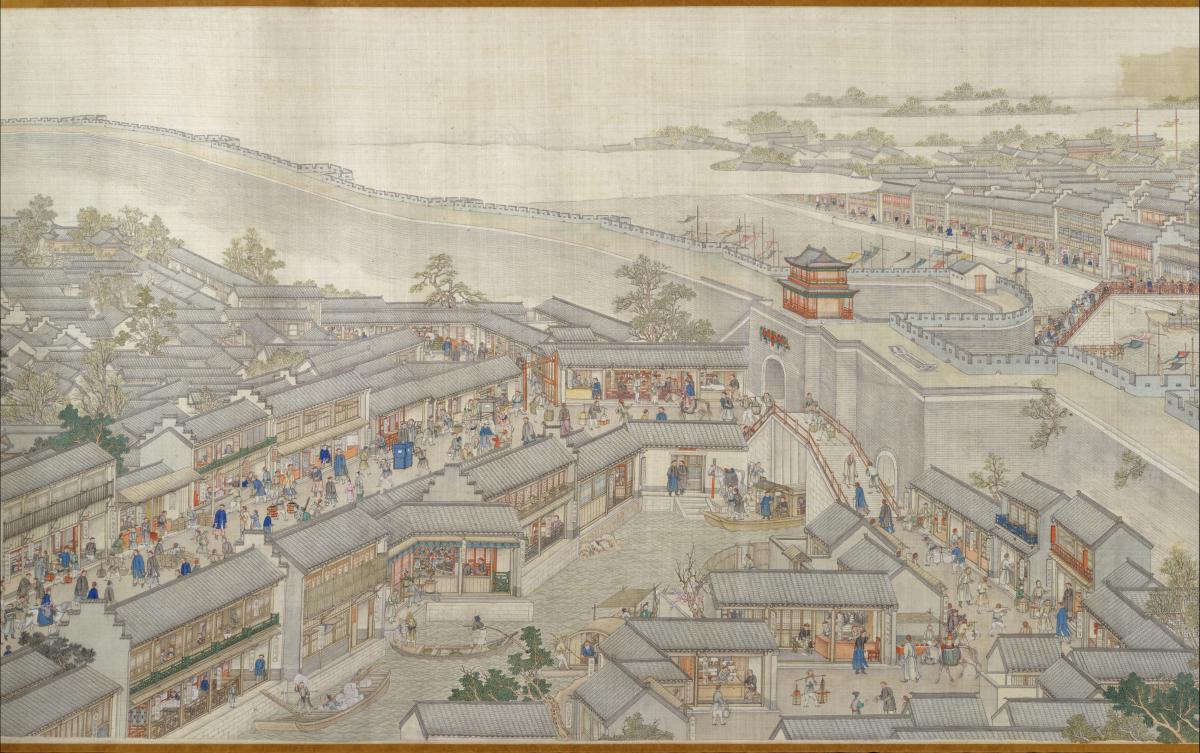

The question of representation also extends to the finely detailed depictions of urban scenes, which bustle with a multitude of shops, restaurants, and markets. James Cahill, Professor Emeritus, History of Art, University of California, Berkeley, and author of the forthcoming Pictures for Use and Pleasure: Vernacular Painting in High Qing China, cautions against seeing the scrolls as presenting accurate depictions of urban life. He thinks of them instead as "hugely elaborated picture-maps." "Xu Yang’s brief, we can assume, was to produce scrolls that recalled the emperor’s experience of the places he visited, and that is what the scrolls give us: grand constructions and performances produced for the imperial visit, hordes of mostly indistinguishable people, quick and generalized looks at the shops and other sights along the way," says Cahill.

The artistic importance of the Qianlong scrolls derives from the blending of the traditional landscape motifs of the Orthodox school with a westernized use of perspective. While landscape is still an important element of the scrolls, it is depicted in relation to the human figure, a shift that emphasizes scale. The blue-green palette is also less in evidence. The infusion of European techniques into Chinese painting can be attributed to the influence of the Jesuits. Since Kangxi’s reign, Jesuit missionaries had served at the court, providing expertise in cartography, geometry, and armaments. They also introduced European drawing techniques and linear perspective. One missionary in particular, Milan-born painter Giuseppe Castiglione, became a court favorite for his ability to blend Chinese and European traditions.

The fragile nature of the scrolls, along with their commemorative nature, has kept them out of public view for centuries. A new NEH-supported website, Recording the Grandeur of the Qing (http://projects.mcah.columbia.edu/nanxuntu/html/scrolls/index.html), has digitized four of the scrolls. The website was produced by Columbia University and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which holds in its collection three of the scrolls. Flash technology allows users to pan the length of each scroll from right to left (the proper direction for reading a handscroll), following the emperors on their tours. “The manner in which the scrolls were digitized, allowing the user to scroll in or out with no loss of clarity is remarkable,” says Madeleine Zelin, professor of modern Chinese history at Columbia University and a project consultant. “We can literally stand in front of the shops, look in, and make our purchases.”

Zelin is also a fan of how the website has linked points on the scrolls to maps, while providing explanations of a specific scene in both English and Chinese. For those not well-versed in the reigns of Kangxi and Qianlong, the website provides a trove of information about their rule, the economy, and the artistic life of the Qing dynasty.

When asked what he personally finds compelling about the scrolls, Hearn, who provided much of the website’s commentary, cites the scale of their ambition. “Each artist had to face a different set of challenges to evoke the sense of pageantry and drama of travel through China.” He admits, however, to being partial to the Kangxi scrolls, finding the earlier style more energetic “They represent a new crescendo in a long tradition of landscape painting. By the time you get to Qianlong, the emphasis is on craftsmanship rather than artistic creativity.”

For his second inspection tour, the Kangxi emperor traveled south from Beijing to Shaoxing. Scroll Three depicts the thirty-mile journey from Ji'nan to Mount Tai in Shandong Province. Soldiers and officials dash through the countryside in advance of the emperor to prepare for his arrival. The scroll culminates with the emperor paying homage at Mount Tai (see cover of magazine).

The temples and shrines that dot the face of Mount Tai attest to its role as a favored place for political and religious ceremonies for more than two thousand years. Powerful spirits were said to reside in the mountain’s rocks, ones capable of granting a good harvest or warding off floods and earthquakes. Daoism also holds that the mountain is the center of yang, the masculine source of life.

Since the artist Wang Hui did not accompany the emperor, he had to rely on the imperial diary, maps, and descriptions by those who had traveled to the region to sketch out the scene. Notice that perspective and scale are not accurately depicted in the scroll. There is no attempt to separate the foreground and background. People are frequently outsized in comparison to the walls or arches they stand next to. The path to the summit of Mount Tai is also clearly depicted, despite being obscured in reality. Instead, the emphasis is on the monumental grandeur of the landscape.

The blue-green palette is also intended to evoke the artistic style of the Tang Dynasty (618–907), which was regarded as the golden age of Chinese civilization. In using the same artistic language to render Kangxi’s journey, Wang created a visual connection between his rule and another majestic era. “The pictorial elements are there to ennoble and enhance the importance and legitimizing function of the trip,” says Hearn.

Qianlong departed on his first inspection tour on February 8 1751. By the time he returned to Beijing on June 26, the emperor had covered almost two thousand miles, having traveled south to the strategic and commercially vital Yangzi Delta region.

Scroll Six, the longest of the twelve scrolls, captures the pageantry of the emperor's arrival in Suzhou, an important trade city located on the Grand Canal, the artificial waterway that connected northern and southern China. From Suzhou, the agricultural riches of the Yangzi Delta, particularly rice, flowed north to Beijing and other cities. The city was also known for its luxury goods trade, serving as a vital hub in China's silk industry.

In this scroll, the influence of western art is very apparent. “There is much more attention given to creating a space that appears measurable and based on the human figure as a scale,” says Hearn. The emphasis on perspective and proportion required artist Xu Yang to abandon grand sweeps of landscape and telescope in on particular scenes. The result is a detailed rendering of Suzhou’s bustling marketplace, as well as the gardens, temples, and canal structure for which the city was famous. The care and detail lavished on the depiction of Suzhou is not surprising given that it Xu’s hometown.