In the early hours of December 13, 1864, twenty-five soldiers surrounded the home of Tom Adams, the leader of an armed band in Knox, Pennsylvania. Drunk and caught by surprise, the bandits surrendered, except for Adams, who dashed upstairs and from a second-story window shot a mounted private. Tearing an opening in the wallboards of a gable, he vaulted into the garden, where he was accosted by soldiers and fatally shot. Adams’s crime? Abandoning the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteers, with which he had served six months in 1863.

The “Bloody Knox” incident, as it became popularly known, is a sound illustration of Pennsylvania’s Civil War-era politics, which pitted antigovernment protestors against federal marshals. “The U.S. government,” explains Robert Sandow, “considered Pennsylvania to be one of the strongest parts of resistance in the entire North.” Sandow, who authored Deserter Country: Civil War Opposition in the Pennsylvania Appalachians, lectures for the Commonwealth Speakers series, sponsored by the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.

Composed of hard-drinking, rough-and-tumble residents, the lumber region in northern Pennsylvania was a hornets’ nest of partisan strife. It doubled as a safe haven for antiwar Democrats and truant soldiers—the nimble Adams, among them. They placed community over country, resented federal intervention, and scorned the presence of industrialists. The Enrollment Act of 1863 was the bane of these hand-to-mouth farmers and loggers, who were needed at home.

As questions of loyalty plagued the Appalachian mountain-sides, partisan lines were drawn. Sandow explains, “Democrats, naturally, wanted to be the defenders of individual rights, but Republicans were saying, ‘Listen, in times of war, there are no political parties. You should put aside partisanship and be patriots in support of the nation.’” As the Civil War raged on Pennsylvania’s southern border, the lumber region was divided by an inner civil war, fought over dinner tables, in newspapers, on storefronts, and in the streets.

After the offices of a Democratic newspaper were gutted and set aflame, an editor urged Democrats “not only to defend their property but to strike back.” “Dissenters used every means possible to defy federal authorities,” writes Sandow, “including lying, intimidation, assault, and murder. Opposition came not from a single class of people but from whole communities.” To evade eligibility and enrollment, Pennsylvanians would conceal family members and neighbors, inflate and reduce their ages, threaten recruitment officers, and, occasionally, wound and murder federal marshals.

Amidst Democratic agitating and Republican moralizing, rumors swirled around the existence of secret societies. Some suspected that the Pennsylvanian Copperheads—men who opposed the policies of the Lincoln administration—were involved in a nationwide conspiracy, the Knights of the Golden Circle. More likely, they established grassroots organizations—what Sandow refers to as “mutual protection societies.” He explains, “They might create a group in which, if one of them was drafted, the other men would help them to stay out of the custody of the marshals.” The Democratic Castle of Clearfield County, for instance, held rallies and clandestine meetings, at which local politicians flirted with treason.

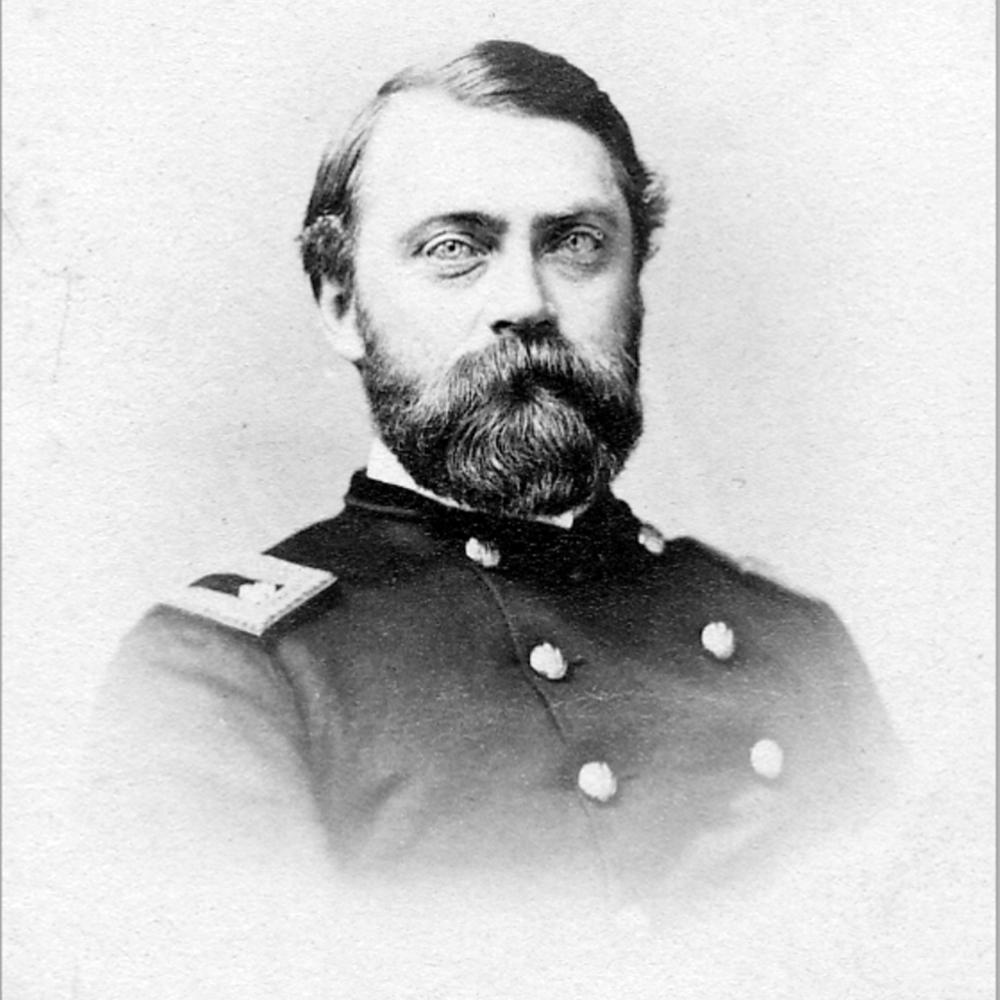

In the latter half of 1864, the federal government took a hard line against Copperheads, dispatching marshals to capture deserters. But, as they were underpaid and unaccustomed to the terrain, their raids met scant success. Within the lumbering counties, the marshals apprehended just over 150 deserters—a far cry from the thousands that were said to have run rampant. The provost-marshal of western Pennsylvania (and a descendent of author Washington Irving), Richard Irving Dodge, and his subordinate officer, Major Frederick A. H. Gaebel, became increasingly zealous, ordering arrests without evidence of desertion. “As military men,” Sandow notes, “they had no respect for civilians who they felt were not doing their duty.”

As the Civil War came to a close, the marshals left Pennsylvania. Their prisoners were required to pay fines or, more often than not, released without a conviction. But, according to Sandow, “the end of the war did not end the controversy over antiwar opposition.” Pennsylvania became one of five states that disenfranchised its deserters, and allegations of Copperheadism carried into the 1880s.

The Civil War was not merely a battle between North and South, but also, one between neighbors. “The reality is,” as Sandow points out, “in every war America’s ever fought, opposition and dissent are common. By remembering this, we’re remembering an important aspect of our own society, our own national life.”