“The Lomaxes didn’t get to Idaho,” says musician and song collector Gary Eller. That’s Eller’s theory of why Idaho-born songs remained silent for decades in dusty archives or family attics. When John and Alan Lomax predicted the devastation that radio would wreak on traditional roots music in the thiries, they took their equipment on the road, traveling up and down Appalachia and as far away as the Mississippi Delta, to record regional music for the Library of Congress. Unlike the Carter Family of Virginia, for example, whose songs were recorded by many people and subsequently played on the radio, the musicians in Idaho were too remote even for the Lomaxes to reach. When radio came to the state, it played the recordings of artists back east, and Idaho’s voice was lost.

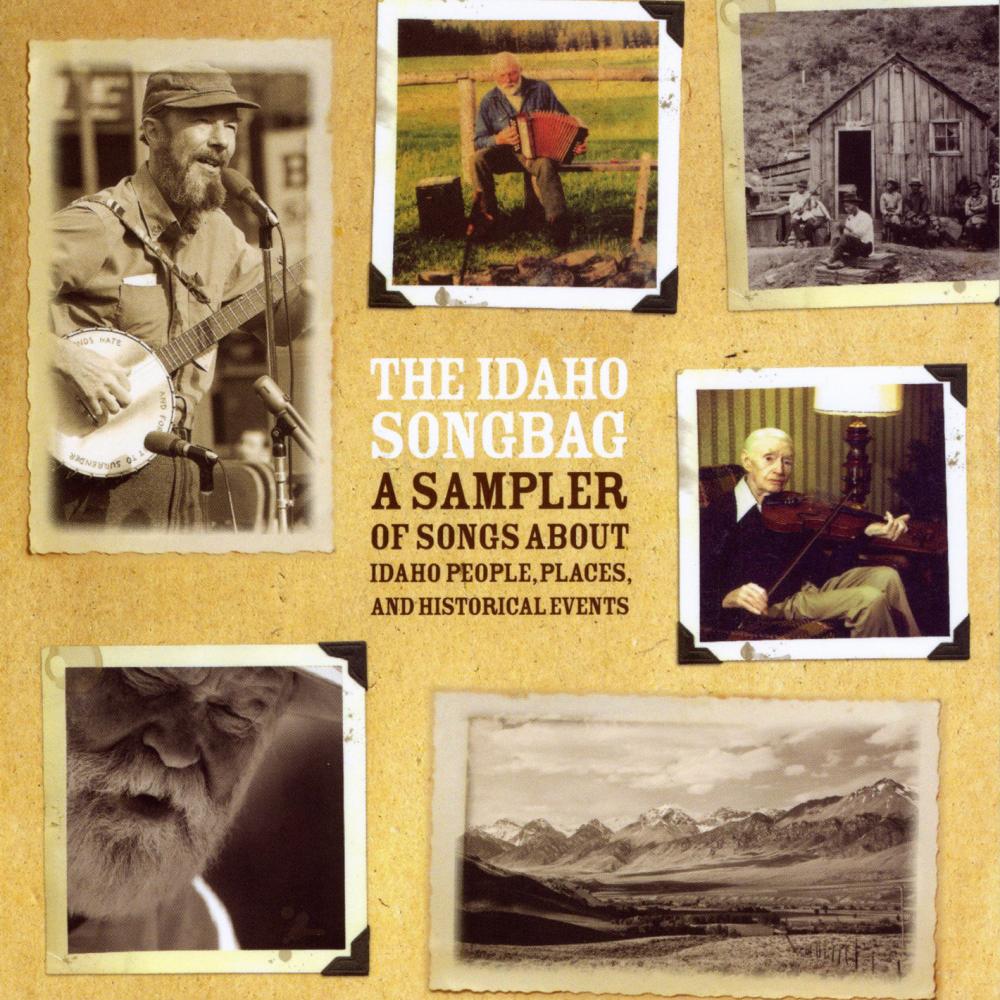

Eller, with assistance from the Idaho Humanities Council, is on a mission to retrieve and preserve Idaho’s songs. He has collected more than two hundred pre-1923 songs, and more than one thousand in all, for The Idaho Songs project at www.bonafidaho.com/idahosongs.htm.

Before a song can be included, Eller tests it. “I take a song that has the word Idaho in it. If I replace Idaho with another state name, and I play the song back and it still makes sense, then it’s not going to make my A list. It’s obviously generic and could be about anywhere or nowhere,” he says. He is particularly fond of event ballads that describe a specific time and place.

His crown jewel for this genre is “Are They Going to Hang my Papa?” a labor protest song written to influence the outcome of the 1907 murder trial against Big Bill Haywood, accused of assassinating former Idaho governor, Frank Stuenenberg. The trial made national headlines, and copies of the song, with a photograph of Haywood’s ten-year-old daughter, Henrietta, prominently displayed, were distributed in Boise and around the country. The New York Times reported thousands of protestors marching through the streets of Manhattan singing it at the time of the trial. Eller is particularly fond of this ballad because it describes an Idaho event that had a national impact. After Haywood was acquitted, the song was forgotten and only two remaining copies of sheet music have been uncovered. It was finally recorded in 2008 by John Larsen, Michelle Graves, and Sean Roger for the project’s first CD, Early Songs of Southern Idaho and the Emigrant Trails.

The earliest known recordings of roots music in Idaho were made circa 1950 by Ione Love Thielke. She called herself “The Musical Poem Recorder of Cascade, Idaho,” and played a balalaika while she sang lyrics by local poets. According to eyewitnesses, Thielke was quite a glamorous figure in the rough timber town, sporting a suit, hat, and gloves whenever she left the house. Her song “Rainbow Stallion of the Owyhees,” words by Mary Edmonson, tells the story of wild horses evading capture; it made Eller’s A list and is included on the Idaho Songbag CD, along with songs about salmon, mining, murders, cowboys, and politics.

One rare tune on the CD recalls a Basque sheep rancher in Idaho. Written and performed by Pinto Bennett—a well-traveled musician who has returned to the Idaho sheep camp where he was born and raised—“El Vasco” is based on a true story Bennett’s grandfather told him about a young man who fled his Basque homeland to escape punishment for killing Spanish soldiers. The man travels to Cuba, then Texas, then California, before finally landing forty miles southeast of Boise, where “he would make his final stand,” dying of natural causes in the 1960s. “It’s a true story, but I filled in the blanks,” admits Bennett. According to Eller, the song is unique because it encompasses the rich musical traditions of the Basque, a prominent immigrant group in the state, with a story particular to Idaho and not just about the old country.

From archives in Melbourne, Australia, to lonely shacks tucked away in isolated mining towns, Eller has discovered untapped repositories of Idaho culture. “I love the thrill of discovery,” he says. Eller was a chemist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico for thirty years before retiring to Idaho. He says, “It turns out that the techniques and mindset that are necessary to be a successful research scientist also apply here.”

Growing up in rural West Virginia, Eller was steeped in bluegrass and roots music. He says that a coal-mining camp in West Virginia is very similar to a hard-rock mining camp in Idaho, so he’s familiar with the places and people he finds in his search for songs. “I go up in these long hollows in these little towns, and I know what I’m going to find. I’m a guitar-playing guy who likes the old songs—I can relate to people very easily. Music is a great common denominator.”