“Chicago! Chicago, queen and guttersnipe of cities, cynosure and cesspool of the world!” So the young British journalist G. W. Steevens exclaimed upon his visit in 1896. Steevens would make his name as a daring war correspondent, covering exotic battlefields, but he never saw anything quite like the conflict he witnessed in Chicago. He confessed himself unable to express in words the “splendid chaos” of the place, “where the keen air from lake and prairie is ever in the nostrils, and the stench of foul smoke is never out of the throat.” Chicago was at once beautiful and squalid, public-spirited and profoundly corrupt. Its towering office buildings stood amid “a vast wilderness of shabby houses.”

“Some day,” Steevens predicted, “Chicago will turn her savage energy to order and co-operation” and “will become the greatest, as already she is the most amazing, community in the world.”

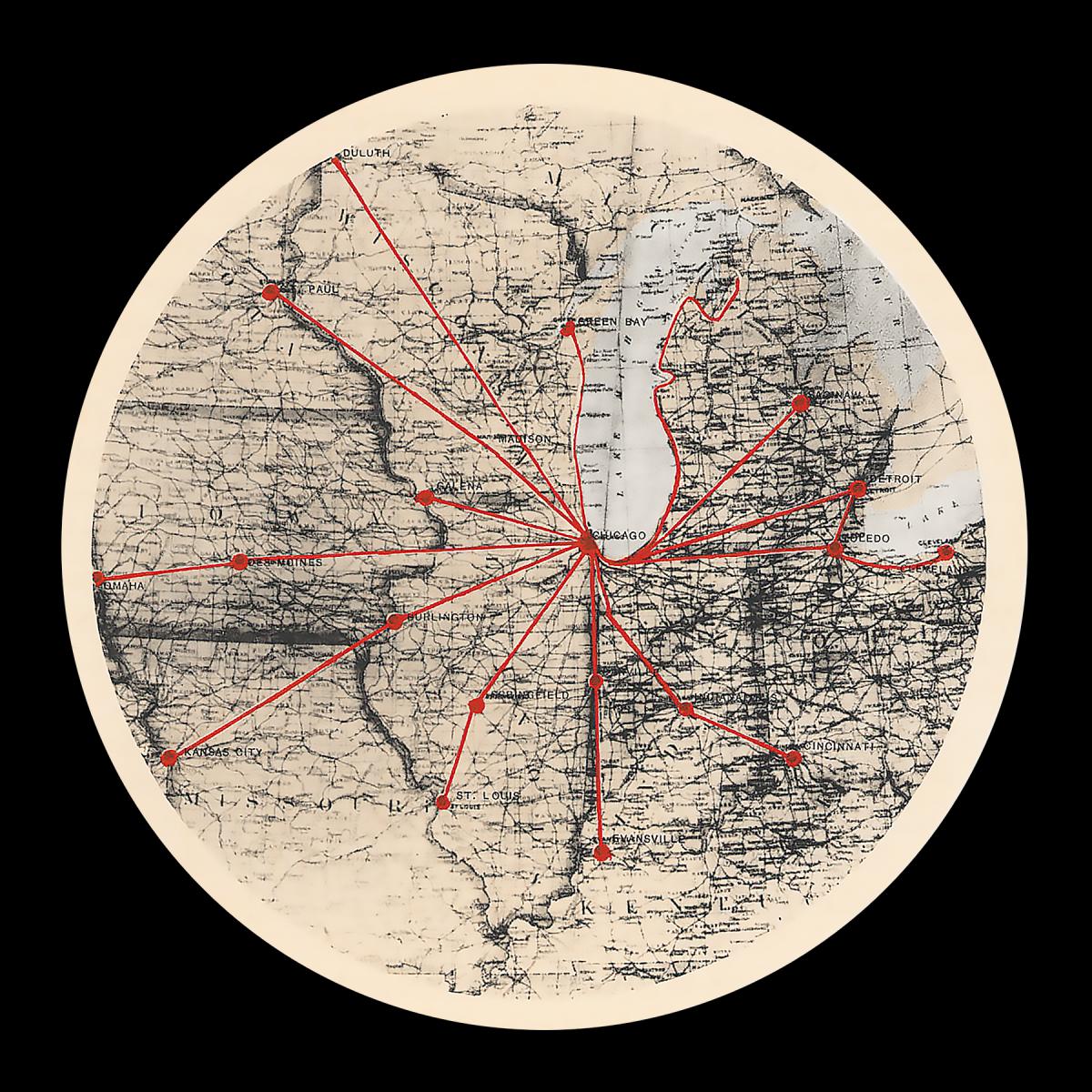

If New York was the country’s largest metropolis, Chicago epitomized the spectacular velocity of urbanization. An obscure frontier outpost in the early 1830s, Chicago grew to 4,470 residents by 1840, making it the ninety-second largest urban center in the nation—just behind Zanesville, Ohio, and Beverly, Massachusetts. A mere fifty years later, it was America’s second city, with a population of 1,099,850. By 1909, the count was two million, and some predicted it would soon be the largest city in the world.

Reform groups asserted that something must be done to reduce inefficiency and improve degraded sections of the city. Business leaders publicly fretted that the city was choking on its own ferocious growth, and that congestion and pollution might drive investors and workers elsewhere. The key, they contended, was to find a way to ensure Chicago’s eminence by reducing obstacles to its expansion and making the most of its strengths.

While several groups and individuals suggested changes in this or that part of Chicago, one organization proposed the wholesale transformation of the city. In 1909, the Commercial Club—an elite private organization consisting of exceptionally successful businessmen devoted to civic improvement—published the Plan of Chicago. Arguably the most influential document in American city planning history, the Plan states that the inefficient, unsightly, and unhealthy American cityscape can and must be redeemed. Championing the rational application of enlightened expertise, it is an exemplary expression of Progressive Era thinking. At the same time, it is a magisterial treatise on the proper relationship between people and the cities they build and inhabit.

The Plan’s creators had no intention of settling merely for order and convenience. They sought to remake the city so brilliantly that it would equal or even surpass the glory of ancient Athens and Rome. Modern Paris, recently rebuilt by Baron Haussmann under Napoleon III, was the contemporary model the planners had most in mind. The club would likely not have undertaken the Plan, however, nor would the result have been so ambitious or eloquent, had it not had among its members the architect Daniel H. Burnham.

With his partner John Wellborn Root, who died early in 1891, Burnham was in the vanguard of the skyscraper revolution that brought renown to Chicago architecture. Burnham’s transformation into city planner came with his heroic efforts in directing the construction of the triumphant 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park, noted for its dazzling array of colossal neoclassical buildings, all painted snowy white. The exposition inspired Chicagoans to rethink their actual city on the elegant model of the transitory one within the fair’s gates. Myriad proposals surfaced for enhancing the lakefront, several by Burnham; but his vision for Chicago would wait several years while he was asked to focus his energy on other cities.

Just after the turn of the century, Burnham served with New York architect Charles McKim, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (whose famous father had worked with Burnham on the Columbian Exposition) on the commission whose recommendations transformed the District of Columbia’s unseemly downtown into the National Mall. Next, he led a three-man team chosen to present a design for revitalizing downtown Cleveland. The Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco invited Burnham to prepare a comprehensive city plan, which, despite the opportunity afforded by the 1906 earthquake, never gained popular support. Before the San Francisco plan was completed, Burnham left his young associate Edward H. Bennett in charge and sailed to the Philippines, recently annexed by war, to redesign Manila and a summer administrative center in Baguio. Shortly after his return, he at last refocused his attention to Chicago.

While the Plan of Chicago is popularly known as the Burnham Plan, it was as much the club’s undertaking as it was his. About three dozen members served on an evolving cluster of committees dealing with different components of the city, meeting hundreds of times over a two-and-a-half-year period. They raised $80,000 to finance the project. Like Burnham, these men gave their time pro bono. Still, he was the acknowledged leader, and Bennett, who turned thirty-five the year the Plan appeared, was his indispensable assistant. Burnham employed several talented individuals to bring the text visually to life. The most important of these was the American artist Jules Guerin, whose pastel-hued renderings infuse the Plan with seductive allure.

Burnham prepared a handwritten draft of approximately three hundred pages. Following his advice, the club hired Charles Moore to edit this into a final text. Burnham had met Moore, who would become his adulatory biographer, while working on the Washington, D.C., plan. The 164-page Plan of Chicago, with the dimensions and heft of a yearbook, was luxuriously produced in “a deluxe limited special edition” of 1,650 individually numbered copies. The volume appeared on July 4, 1909, as if to declare the city’s independence from the tyranny of disorder. It was distributed to local and national leaders, including President Taft.

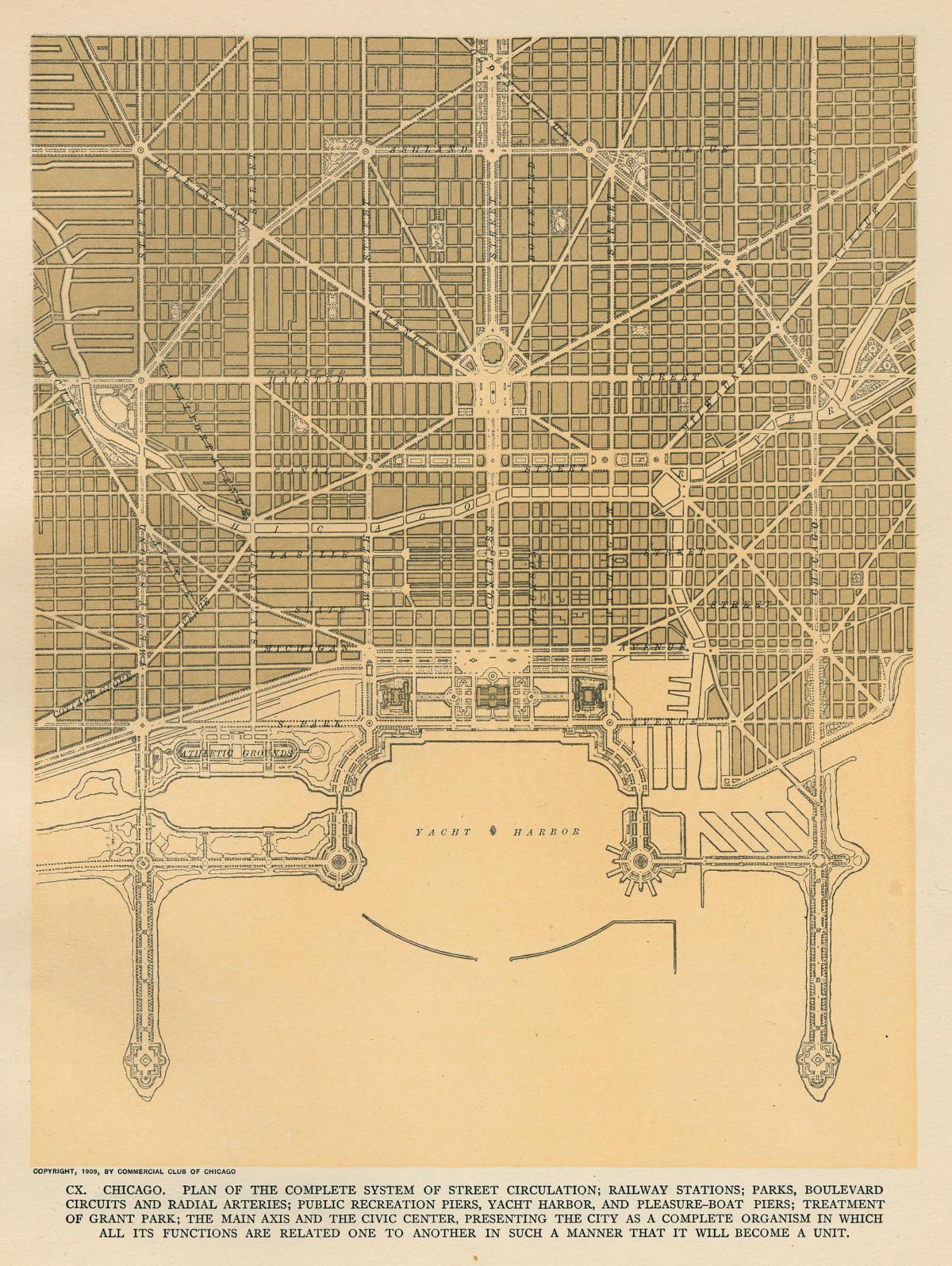

Readers opened the Plan of Chicago to behold a host of observations and proposals, large and small, abundantly illustrated with over 140 paintings, renderings, elevations, diagrams, and photographs. Far more than a dry inventory of recommendations, it maintained that Chicago must think of the city and the surrounding area as an integrated region, and in doing so must pursue certain ideals: convenience, efficiency, order, cleanliness, health, beauty, harmony, unity, and dignity. Taken together, these ideals define what is called the City Beautiful movement, which saw them embodied most fully in the stately lines, formal balance, and grand scale of Beaux Arts architecture. The Plan asserts that Chicago must seize its rightful position at the forefront of Western civilization. To do otherwise would be to shun the extraordinary advantages at hand, beginning with the natural landscape dominated by the lake and prairie. “These two features, each immeasurable by the senses, give the scale. . . . Whatever man undertakes here should be either actually or seemingly without limit.”

In the Plan’s view, practical and aesthetic considerations need not oppose each other. The best way to build a prosperous city is to make it beautiful and healthy. Dirt, noise, and squalor are far more costly than any attempt to banish them. The Plan followed the Progressive argument that a great setting makes for a great people, while ugly and unwholesome conditions debase all who must endure them. The lake shore “by right belongs to the people,” and must be treated “as park space to the greatest possible extent.” Here is Chicago’s “one great unobstructed view,” begetting “calm thoughts and feelings” while affording “escape from the petty things of life.”

In a metropolis of such voracious dynamism, it was impossible to think too big. “At no period in its history has the city looked far enough ahead,” the Plan exhorted. “Whatever the labor and however large the cost, the result has always been found more than compensation for the outlay.” This closely resembles the famous quotation commonly attributed, though never definitively, to Burnham: “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized.” No citizen, the Plan maintained, “should hesitate to commit himself to the largest and most comprehensive undertaking; because before any particular plan can be carried out, a still larger conception will begin to dawn, and even greater necessities will develop.”

Thanks to an unprecedented promotional campaign as well as to the compelling prose and illustrations through which the Plan presents its case, a striking number of the proposals were implemented. The campaign began with persuading the city to adopt the Plan as its official blueprint and to appoint a large semipublic committee, the Chicago Plan Commission, to lobby for its realization. The commission launched a relentless barrage of speeches and rallies. It produced 165,000 copies of an inexpensive edition of the Plan, which were distributed to likely voters in bond authorization referendums, a textbook version that became part of the eighth-grade public school civics curriculum, and even a promotional film, titled A Tale of One City.

Improvements based at least partly on the Plan include many of Chicago’s signature features: the construction of much of the lakefront parks; the widening of streets and a bi-level Michigan Avenue; the double-decker Michigan Avenue Bridge (opening up the development of the so-called Magnificent Mile north of the Chicago River); the building of Union Station and a central post office; the erection of Navy Pier; the straightening of the Chicago River; and the development of the Cook County Forest Preserve.

Some proposals made little headway. The railroad lines and stations that were so critical to the city’s and the country’s economy were never rationalized, and only one of the several diagonal streets that were to improve traffic was ever cut. The most original proposal, a grand, multi-structure civic center several blocks west of the downtown, did not get off the ground. Instead, the mammoth Circle Interchange, connecting three major expressways, now dominates the area.

In some respects, the Plan has become the kind of symbol it intended the civic center to be. It has come to stand for the idea of planning itself, and for doing so on the largest and boldest scale. The Plan helped establish the planning profession and prompted numerous other city plans for places large and small, several of them prepared by Bennett (Burnham died in 1912 at the age of sixty-six). At the same time, it prompted other ambitious regional planning efforts, including the Regional Plan Association, which released a comprehensive plan for the tristate New York metropolitan area in 1929. To this day, backers of major planning proposals invoke the spirit of Burnham as an endorsement of their own ideas.

While the Plan was widely popular, it was not free of criticism. George E. Hooker of the City Club complained of the Plan’s relative neglect of housing issues and its incomplete treatment of transportation. As Robin F. Bachin notes, Jane Addams’s Hull-House associate and founder of the University of Chicago Settlement, Mary McDowell, criticized its inadequacies in addressing living conditions among the poor. Chicago Federation of Labor president John J. Fitzpatrick was particularly blunt about the Plan’s disregard of the city’s vast population of working people. In refusing to serve on the Chicago Plan Commission, he charged that its main purpose was to assist the same commercial and industrial interests who worked their employees “long hours at starvation wages.” While talking of beautifying the city, they ignored “the cry of despair among the men, women, and children whose only fault is that they must toil to live.”

Some of the most well-known twentieth-century urbanists attacked the Plan. Writing in 1961, historian and cultural critic Lewis Mumford criticized it for being primarily devoted to enhancing real estate prices, terming it the premier example of modern “baroque planning.” It showed “no regard for the neighborhood as an integral unit, no regard for family housing, no sufficient conception of the ordering of business and industry themselves as a necessary part of any larger achievement of urban order.” In The Death and Life of Great American Cities (also 1961), Jane Jacobs, though no ally of Mumford, disparaged Burnham’s emphasis on monumentality and argued that the Plan undermined the vitality of local communities.

Some of the criticism is certainly justified. Preoccupied with the efficient movement of traffic and goods and the city’s physical appeal, the published Plan pays limited attention to social services, housing, and the quality of neighborhood street life. Its solution to the problem of slums is not to seek out their root cause in fundamental inequities but to remedy them through “the cutting of broad thoroughfares through the unwholesome district” and strictly enforcing sanitary regulations. It holds out the threat of public control if negligent property owners do not shape up. But the sensibility behind the proposals is not that of most Chicagoans. The perspective of Guerin’s enticing renderings is tellingly top-down, almost always from a great height or distance.

Burnham did in fact address some of the social issues the Plan is criticized for omitting. As architectural historian Kristen Schaffer points out, his draft discusses social as well as physical aspects of the city in often pointed detail. He recommended a larger role for government in overseeing the lives of Chicago’s residents in such areas as education, health, and other essential services. He called for government supervision of utilities and hospitals and the creation of day-care facilities for children of working women. His proposals for construction projects include school buildings that are brightly lit, fully ventilated, and equipped with playgrounds; police stations where the procedures of law and order are “open to the public gaze”; and convenient, numerous, and appealing public bathrooms of “perfect sweetness.” Moore removed or extensively edited much of Burnham’s discussion of such topics. While the precise reason is unknown, meeting minutes reveal the planners instructed him that “the text of the book should emphasize the fact that the Plan is a business proposition.” It conveys the vision of commercial leaders who believed, albeit with good intentions, that their interests and those of the city were the same, and that what was good for business benefited everyone.

Perhaps the Plan’s most important legacy is its contention that the world in which we live is neither inevitable nor inalterable, and we must constantly be attuned to how we can make it better. The Plan states at the outset that it is meant “to direct the development of the city towards an end that must seem ideal, but is practical.” In doing so, it argues, we need to think holistically, considering Chicago as a complex system or organism—the Plan employs both mechanical and organic metaphors—with a special relationship to the region, the nation, and the world. And all efforts to renew and remake it must be animated by the idea of a humane and productive and beautiful city that truly stirs the blood and captures the imagination.