When Thomas Carlyle sat down in 1834 to write The French Revolution: A History, he wanted to do more than chronicle the mere procession of events. He wanted readers to smell the fear in the streets during the Terror, to taste the decadence of the Bourbon monarchy, to observe the sartorial cavalcade when the Estates-General meets for the first time since 1614, to picture blood spilling from guillotines. To accomplish his task he marshaled the same tools used by novelists—shifting point of view, imagery, and telling details—and borrowed tone and grandeur from Homer, Virgil, and Milton. What sprang forth from Carlyle’s pen was not a dry account of the French Revolution, but a book brimming with passion and philosophy, one that offered a new style of storytelling that influenced a generation of Victorian writers.

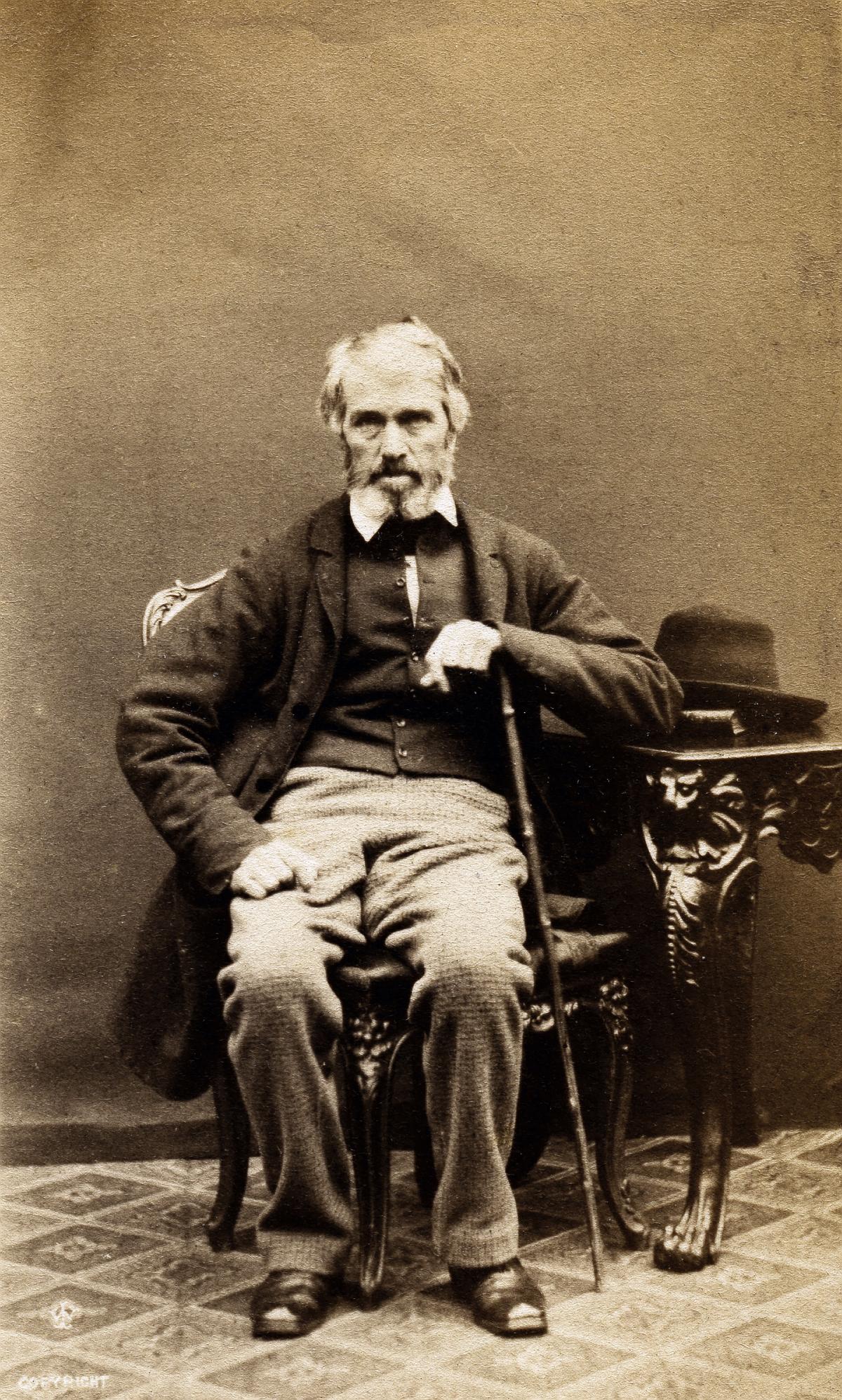

That Carlyle would produce such a fervent account is somewhat surprising given his dour upbringing. Born in Ecclefechan, Scotland, in 1795, he was the eldest son of a household defined by his father’s temper and consuming devotion to Calvinism. A bright but sickly boy, he mastered French and Latin, and excelled at mathematics. His father agreed to let him attend university provided he study to become a minister. At fourteen he enrolled at the University of Edinburgh, continuing his math studies, tutoring students on the side, and devoting his free time to reading. As he grew more confident socially, he began to participate in debate clubs, where he was celebrated for his wit.

Each year Carlyle spent at Edinburgh, the less inclined he was to fulfill his promise to become a minister. Near the end of his studies, he grudgingly enrolled in a nonresidential divinity course, convinced that he would never finish, but aware of his promise to his parents. In 1814, with neither divinity nor arts degree in hand, Carlyle took his first in a series of teaching jobs, first in Annan, later in Kirkcaldy. His days were spent instructing indifferent young men, while his nights were devoted to literature. In the spring of 1817, he abandoned all pretense of becoming a minister.

A growing disaffection with teaching and a surety that his future career lay in writing led Carlyle to give up his teaching post and move back to Edinburgh in the fall of 1818. He cobbled together a meager living doing translations, tutoring, and hack writing. Carlyle continued his voracious reading, looking for hints of craft and style that he could adopt. He considered Coleridge “very great but rather mystical, sometimes absurd.” Essayist William Hazlitt was “worth little, tho’ clever.” Alexander Pope was “eminently good,” while Thomas Gray was found to be “very good and diverting.” Carlyle lamented the death of Washington Irving: “It was a dream of mine that we two should be friends!” He regarded Byron and those like him to be “opium eaters,” people who “raise their minds by brooding over and embellishing their sufferings, from one degree of fervid exaltation and dreamy greatness to another, till at length they run amuck entirely, and whoever meets them would do well to run them thro’ the body.”

He found solace and inspiration in an unlikely place: the writings of the German Romantics. After struggling to teach himself German, he made it through Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, in which God and Mephistopheles fight over the soul of scholar Heinrich Faust. Goethe’s ideas and writings electrified him, prompting him to encourage his friends to persist with studying German, because “in the hands of the gifted does it become supremely good.” It wasn’t long before Carlyle was privileging German over French literature. His enthusiasm led to a book-length essay on Friedrich Schiller and then a translation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship that earned him his first big paycheck, in the amount of £180.

In October 1824, Carlyle took a trip to France that he later claimed helped him to write the vivid descriptions in The French Revolution. He did not go to Paris as a young man taking his grand tour, ready to indulge in the delights of French culture; he went as a man who, despite having renounced life as a minister, still viewed the world through the lens of Scots Presbyterianism. After only a few days in Paris, he observed: “France has been so betravelled and beridden and betrodden by all manner of vulgar people that any romance connected with it is entirely gone off ten years ago; the idea of studying it is for me at present altogether out of the question; so I quietly surrender myself to the direction of guide books and laquais de place [local flunkeys], and stroll about from sight to sight.”

Carlyle grudgingly respected Napoleon and his attempts to rationalize French civil life, but held contempt for anything that smacked of the ancien régime. In Carlyle’s estimation, Protestant Germany emphasized work, faith, and personal responsibility, while Roman Catholic France revered whimsy, secularism, and voluptuous delights. “They cannot live without artificial excitements, without sensations agréables. Their houses are not homes, but places where they sleep and dress; they live in cafés and promenades and theatres; and ten thousand dice are set a-rattling every night in every quarter of their city. Every thing seems gilding and fillagree, addressed to the eye not the touch. Their shops and houses are like toy-boxes; every apartment is tricked out with mirrors and expanded into infinitude by their illusion,” wrote Carlyle.

In October 1826, Carlyle wed. Jane Welsh was a woman of formidable intelligence with literary ambitions of her own whom Carlyle had courted for five years. She had had reservations about the man who talked endlessly about his poor health and tried to impress her with his knowledge of German literature. Jane’s mother had found Carlyle’s lack of steady employment troublesome and had forbidden her daughter from encouraging his attentions. But Jane had defied the maternal edict. “I am as nervous as if I were committing a murder,” she’d written in her illicit correspondence with Carlyle, who won out over Jane’s other suitors by engaging her mind. In return for his persistence, Carlyle earned a wife who championed his aspirations, served as his first reader, and tolerated the financial uncertainty that came from living by his pen.

After the wedding, they set up house in Craigenputtock, a farm in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. “It is certain that for living and thinking in, I have never since found in the world a place so favourable. . . . How blessed, might poor mortals be in the straitest circumstances if only their wisdom and fidelity to Heaven and to one another were adequately great!” Carlyle also began to correspond regularly with Ralph Waldo Emerson, with whom he shared an interest in transcendentalism, as well as Goethe, whom he regarded as a literary mentor. At the farm, Carlyle wrote Sartor Resartus, a satirical work featuring a fictional German philosopher and a critique of utilitarianism and British society.

By 1831, the isolation of Craigenputtock had made it an inhospitable home to both Carlyles, so they decamped to London. Living in rural Scotland had kept Carlyle from mingling with the London literati to the detriment of his career, but once in town Carlyle quickly expanded his circle, falling into an easy friendship with John Stuart Mill.

Following the publication of Sartor Resartus, Mill suggested Carlyle tackle the French Revolution. Unable to produce a history Mill had contracted to write, he felt the project would suit Carlyle, who had penned essays about Voltaire, Diderot, and the Diamond Necklace affair, in which Marie Antoinette was falsely accused of defrauding the crown jewelers. To help Carlyle along, Mill also handed over the library of books and pamphlets he had collected. Carlyle agreed and plunged into the project. “I am busy constantly studying with my whole might for a Book on the French Revolution. It is part of my creed that the only Poetry is History could we tell it right,” he wrote Emerson.

After two years of study, Carlyle started to write in September 1834. He predicted that he would finish the book by March 1835, but after finishing three chapters he realized his ambitions did not match his progress. One volume would not suffice, so his plan changed: in December, one book became two; in January 1835, he determined he would need to write three.

In February 1835, Carlyle shared a draft of the first book with Mill. At midnight on the evening of March 6, a hysterical Mill appeared at Carlyle’s door and delivered the news that one of his servants mistook Carlyle’s manuscript for wastepaper and threw it in the fire. “Poor manuscript, all except some four tattered leaves, was annihilated!” he wrote of the upsetting news.

Carlyle now had to reconstruct the first book. There were no drafts or backup copies from which to work. He didn’t take notes. His method was to read, then write like mad. Sections he found lacking were tossed in the fire. “I was as a little Schoolboy, who had laboriously written out his Copy as he could, and was shewing it not without satisfaction to the Master: but . . . the Master had suddenly torn it, saying: ‘No, boy, thou must go and write it better.’”

Mill felt terrible and asked if Carlyle would accept £200 to “repair . . . the loss . . . of time and labour—that is of income?” Embarrassed by the offer, but in financial straits, Carlyle accepted half the sum. Wanting to demonstrate there were no hard feelings, Carlyle suggested that Mill read the first section of book two. Grateful for the renewed trust, Mill agreed, but suggested that Carlyle give the manuscript to Harriet Taylor for safekeeping. Carlyle did not approve of Mill’s intimate relationship with the married Taylor. He also believed that she played a part in the accident, as Mill had confessed he’d read the manuscript to her. Carlyle never delivered the pages and the book went to print without Mill’s comments.

Rewriting the first book was torture for Carlyle. The destroyed manuscript became an ideal in his mind, allowing him to despair at the poor quality of the new draft. He initially made good progress, but abandoned its writing in favor of reading the “trashiest heap of novels.” After his reading holiday, he began again, completing the first and second chapters by the beginning of May. By September 1835, he had rewritten book one. He finished the second book at the end of April 1836. Book three went slower. “The Revolution History goes on about as ill as anybody could wish,” he wrote his brother. “I sit down to write, there is not an idea discernible in the head of me; one dull cloud of pain and stupidity; it is only with an effort like swimming for life that I get begun to think at all.” On January 12, 1837, two years after he began, Carlyle completed book three, “ready both to weep and pray.”

WHEN CARLYLE BEGAN HIS BOOK he did so with the idea of writing an epic poem about the French Revolution. “The old Epics are great because they (musically) show us the whole world of those old days: a modern Epic that did the like would be equally admired, and for us far more admirable. But where is the genius that can write it? Patience! Patience!” he wrote in February 1831.

What emerged from Carlyle’s pen was not an epic poem, but an epic history. Although full of lyrical writing, The French Revolution: A History is, of course, a work of prose. Many standard conventions of the epic are absent, such as opening mid-story and intervention of the gods into human affairs. Carlyle does, however, invoke Clio, the muse of history, to guide him and his reader. And like the epics, The French Revolution tells a story that is central to the history of its people. But instead of the founding of Rome or the victory over Troy, Carlyle writes of a revolution that unseated a long-standing monarchy and gave way to the new France.

To judge it as a conventional work of history would not be fair. Writing more than four decades after the French Revolution, Carlyle had enough material to reconstruct the outlines of what had happened. Printing presses ran constantly during the revolution, turning out broadsheets and pamphlets. And, in the aftermath, those who managed to avoid the guillotine penned memoirs. But, despite such abundant sources, Carlyle rejected the model offered by Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, with its objective approach and use of notes to document sources. If he acted as the disinterested narrator, he would remain above the action, unable to put the reader outside the walls of the Bastille the way that Homer put his reader outside the walls of Troy. Carlyle admired Gibbon, citing his ability to offer his readers a “rich and various feast,” but he was not interested in the lessons of history. Instead, he wanted to write a book that captured the frenzy of the revolution, its dramatic power, its most unforgettable details.

To do this, Carlyle had to invent a new way of writing history. From the beginning of book one, Carlyle calls upon readers to move with him through time and space. He asks us to gaze upon the dying King Louis XV and to follow the newly crowned Louis XVI as he retires to his chambers. He constantly assumes the roll of fortune teller. When he first introduces Marie Antoinette, he writes: “Meanwhile the fair young Queen, in her halls of state, walks like a goddess of Beauty, the cynosure of all eyes; as yet mingles not with affairs; heeds not the future; least of all, dreads it.”

For the procession that marks the opening of the Estates-General, Carlyle invites us to “take our station on some coign of vantage.” From his omniscient perch, Carlyle sketches vivid descriptions of the men who will influence the course of the revolution, while speculating as to who will emerge as “king.” Will it be Jean Paul Marat, a “squalidest bleared mortal, redolent of soot and horse-drugs” or the “swart burly-headed” Riquetti Mirabeau, who cuts a “fiery rough figure, with black Samson-locks under the slouch-hat”? Or the “meanest” of the six hundred, Maximilien Robespierre, “that anxious, slight, ineffectual-looking man, under thirty, in spectacles . . . complexion of a multiplex atrabiliar colour, the final shade of which may be the pale sea-green”? Carlyle’s character studies double as moral judgments: He likens Mirabeau to a biblical hero, while painting Marat and Robespierre in putrid terms. He uses their exteriors to caricature their souls.

The combination of eyewitness account and commentary runs throughout the book, allowing Carlyle to make us part of the action. The storming of the Bastille: “A slight sputter;–which has kindled the too combustible chaos; made it a roaring fire–chaos! Bursts forth Insurrection, at sight of its own blood (for there were deaths by that sputter–of fire), into endless rolling explosion of musketry, distraction, execration;–and over head, from the Fortress, let one great gun, with its grape-shot, go booming, to show what we could do.” Carlyle uses the third person to describe the scene and action, then switches to the royal “we” (more precisely the antiroyal “we”) as he and his readers join the mob as it takes the Bastille.

For Louis XVI’s beheading, he puts us in the crowd: “Executioner Sampson shews the Head: fierce shout of Vive la République rises and swells; caps raised on bayonets, hats waving; students of the College of Four Nations take it up, on the far Quai; fling it over Paris. . . . And so, in some half-hour it is done; and the multitude has all departed. Pastrycooks, coffee-sellers, milkmen sing out their trivial quotidian cries.” Carlyle’s use of present tense to describe the sequence of events lends an almost journalistic quality to his work. He is in the moment, recording the scene as it happens, breathing energy and emotion into history.

By taking this approach Carlyle recognized he was doing something new and different, and it terrified him. After writing the first two pages of the book in September 1834, he reported to his brother Jack that: ”I am altering my style too, and troubled about many things; bilious too in these smothering windless days. It shall be such a Book! Quite an Epic Poem of the Revolution: an Apotheosis of Sansculottism! Seriously, when in good spirits, I feel as if there were the matter of a very considerable Work within me; but the task of shaping and uttering it will be frightful. Here, as in so many other respects, I am alone: without models, without limits (this is a great want); and must—just do the best I can.”

Just how different what Carlyle was doing can be seen by comparing the opening three sentences of Gibbon’s work with his. Gibbon begins:

In the second century of the Christian Æra, the empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilized portion of mankind. The frontiers of that extensive monarchy were guarded by ancient renown and disciplined valor. The gentle but powerful influence of laws had cemented the union of the provinces.

Carlyle starts:

President Hénault, remarking on royal Surnames of Honour how difficult it often is to ascertain not only why, but even when, they were conferred, takes occasion in his sleek official way to make a philosophical reflection. ‘The Surname of Bien-aimé (Well-beloved),’ says he, ‘which Louis XV bears, will not leave posterity in the same doubt. This Prince, in the year 1744, while hastening from one end of his kingdom to the other, and suspending his conquests in Flanders that he might fly to the assistance of Alsace, was arrested at Metz by a malady which threatened to cut short his days.’

Gibbon uses the past tense and speaks in an authoritative tone as he provides a measured account of the state of the Roman Empire. For Gibbon, the past is a fixed and ordered place where the outcome of events is certain. Carlyle, on the other hand, begins with a philosophical quip and the tale of Louis XV’s near demise more than forty years before the revolution. The use of the present tense (“he says”) puts the reader directly in the scene. Carlyle doesn’t ask us to sit at his feet as Gibbon implicitly does, he asks us to gallivant through the revolution with him, experiencing events as they happen. In Carlyle’s history, the outcome of events may be foreshadowed but is never certain.

The episode that marks Carlyle’s opening is indicative of the structure of the book itself. Rather than provide a narrative-style account, he offers a procession of vignettes that tell the story of the revolution. This format suits Carlyle’s preference for dramatic moments over procedural ones. Consequently, his emphasis does not always match the significance of events. For example, the mutiny by French troops in the town of Nancy in the summer of 1790 and the machinations of the Legislative Assembly receive the same number of pages. The mutiny was an episode that showed France’s disarray, but the failure of the Legislative Assembly to govern during 1791–1792 led to a constitutional crisis that further inflamed the revolution. What Carlyle emphasizes can be attributed to favoring the dramatic, but it also stems from his positioning of the mob, particularly the Paris mob, at the center of the story. While he openly admires men like Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, the Comte de Mirabeau, for his handling of the parliament and the king and queen, Carlyle never turns him into a Hector. Instead, the hero of his history is the mob—they are like Achilles, full of rage and anger, eager to fight.

In his other writings, Carlyle questioned the ability of men to organize themselves, believing they need to have order imposed on them. Yet in The French Revolution, Carlyle time and again praises the mob. “Other mobs are dull masses; which roll onwards with a dull fierce tenacity, a dull fierce heat, but emit no light-flashes of genius as they go. The French mob, again, is among the liveliest phenomena of our world. So rapid, audacious; so clear-sighted, inventive, prompt to seize the moment; instinct with life to its finger-ends! That talent, were there no other, of spontaneously standing in queue, distinguishes, as we said, the French People from all Peoples, ancient and modern.” The French mob succeeds because it is not artificially constructed, but organic: “Your mob is a genuine outburst of Nature; issuing from, or communicating with, the deepest deep of Nature.”

Carlyle’s attention to the mob comes from the character of the revolution itself. There would be no French Revolution without the French people questioning the monarchy and taking action. But by focusing on the mob and what happens in the streets to everyday people, Carlyle was laying the seeds for the approach taken by social historians more than a century later. In showing the actions of ordinary people, he demonstrated that a rich history could be crafted when the king and parliament share the stage with the butcher and the fishmonger.

THE FIRST REVIEWS OF The French Revolution: A History began appearing in mid-July 1837, their placement arranged by Carlyle, Mill, and the publisher. Writing in the London and Westminster Review, Mill called The French Revolution a “most original book,” one whose “every idea and sentiment is given out exactly as it is thought and felt, fresh from the soul of the writer, and in such language . . . as is most capable of representing it in the form in which it exists there.” Mill compared the book to the Iliad and Aeneid: “This is not so much a history, as an epic poem . . . the history of the French Revolution, and the poetry of it, both in one; and on the whole no work of greater genius, either historical or poetical, has been produced in this country for many years.” Mill’s words pleased Carlyle. “No man, I think, need wish to be better reviewed. You have said openly of my poor Book what I durst not myself dream of it, but should have liked to dream had I dared,” he wrote Mill upon receiving the review.

William Makepeace Thackeray, a young journalist and aspiring novelist, gave it a favorable review in the Times, although he described it as “prose run mad.” Criticism of the style of writing was a common theme among those who did not care for the book. They objected to its prose being too German. For Carlyle who revered German authors, their complaint was almost a compliment.

He could also rejoice in its reception by other writers, receiving praise from Robert Browning, John Forster, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Dickens relied heavily on the book while writing A Tale of Two Cities. Emerson claimed Carlyle as “my bard,” while Thoreau regarded the book as “a poem, at length got translated into prose; an Iliad.” Mark Twain would later call it one of his favorite works.

Kathleen Tillotson, a scholar of Victorian literature, believes The French Revolution had a profound influence on a generation of Victorian novelists, including Thackeray and the Brontës, showing them “the poetic, prophetic, and visionary possibilities of the novel.” Indeed, George Eliot observed in 1855 “there has hardly been an English book written for the last ten or twelve years that would not have been different if Carlyle had not lived.” For Eliot and others, Carlyle’s charm lay not in his history, but in his literary talents: “No novelist has made his creations live for us more thoroughly than Carlyle has made Mirabeau and the men of the French Revolution, Cromwell, and Puritans.”

The publication of The French Revolution and its popularity solved Carlyle’s financial problems, earning him not only acclaim but profits and lecture invitations. More books followed on Chartism, the political and social reform movement that swept England from 1838–1848, the role of heroes in history, a study of Oliver Cromwell, and a biography of Frederick II of Prussia. But The French Revolution would remain Carlyle’s greatest achievement, providing a literary history for a post-revolutionary age.