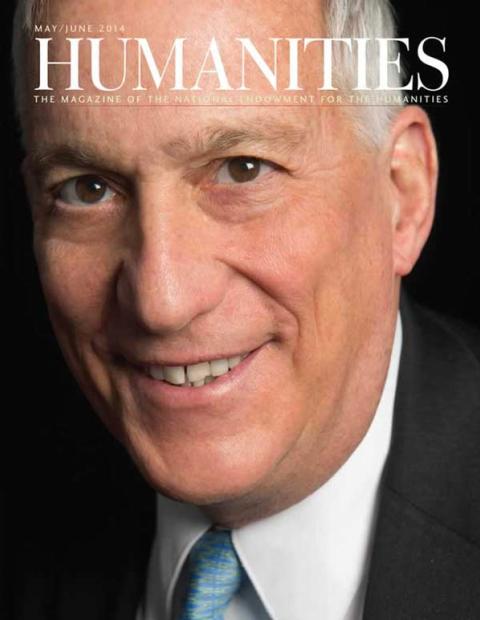

Walter Isaacson, the 43rd Jefferson lecturer, is a journalist and a writer who worked for many years at Time, where he served as editor from 1996 to 2001. He is also an acclaimed biographer, whose subjects have included Henry Kissinger, Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin, and Steve Jobs. In 2001, he became the CEO of CNN, where he worked until 2003, when he became the president and CEO of the Aspen Institute. On February 6, 2014, he sat for an interview with David Skinner, editor of Humanities magazine.

HUMANITIES: You were born in New Orleans and grew up there in the 1950s and ‘60s. What was that like?

WALTER ISAACSON: Growing up in the Central City and Broadmoor areas of New Orleans was particularly interesting because you had a racial and economic diversity. And one thing I learned was this: The diversity of a city, like New Orleans, helps add to its creativity. Earlier in the century, Louis Armstrong had grown up in pretty much the same neighborhood. It’s where jazz came from, all the different influences, likewise, with the food or the literature of New Orleans. Even with all of the frictions that diversity causes, as it certainly did in the early 1960s in New Orleans, it led also to friendships and creativity.

HUMANITIES: When did you first become interested in current events, history, and writing?

ISAACSON: I had a friend of the family, an uncle of a friend, Walker Percy, who played a part in this. As a boy, I grew up trying to figure out what Uncle Walker did, because he was a doctor. Other people called him Dr. Percy, but he wasn’t a practicing doctor. And we used to say to Ann, his daughter, What does your dad do? He’s always at home drinking bourbon and eating hog’s head cheese. And then, The Moviegoer came out, when I was about nine years old. And I realized, Oh, you can be a writer when you grow up.’ It was like being an engineer or a doctor or a fisherman, or anything else you could be in Louisiana.

HUMANITIES: What was Walker Percy like?

ISAACSON: He was a kindly gentleman. From his face you could tell he had known despair, but his eyes still smiled. And he had a lightly worn grace to him. An easygoing guy, but there were things roiling underneath. I remember asking him about The Moviegoer and then The Last Gentleman, when it occurred to me that there were some philosophical things he was trying to work out. I asked him about it, and expressed an interest in becoming some kind of writer.

He would say that two types of people came out of Louisiana, preachers and storytellers. He said, “For God’s sake, be a storyteller. The world’s got too many preachers.”

He thought that too many journalists, and writers in general, feel they have to preach. He said it was best to do it the way the best parts of the Bible do, by telling a wonderful tale, and people will get the message on their own.

When I was asked to give the Jefferson Lecture, my mind went back to Walker Percy. He delivered this lecture twenty-five years ago, and I came down to Washington to hear it. I can still remember Lynne Cheney, then chairman of NEH, introducing him. He actually talked about the intersection of science and the humanities.

That’s something that I have been dealing with my whole life. Benjamin Franklin was a truly great scientist and his electricity experiments were the most important empirical studies of that era. His science helped inform his enlightened view of governance, diplomacy, and the balance of power. Likewise, Einstein, a great scientist, truly appreciated arts and the humanities, and they deeply informed his work. And, most clearly of all, Steve Jobs, when we first started working together on the biography I wrote, said, in so many words, I learned to stand at the intersection of the humanities and technology, because I believe that’s where value is created.

Those were the themes that Walker Percy addressed in his novels, which asked, What can science tell us about the human condition, if anything? And what can the humanities tell us about how to deal with science?

HUMANITIES: You studied philosophy too at Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship. What were you researching? And why didn’t you become an academic?

ISAACSON: Well, I was particularly interested in the philosophy of language and the philosophy of meaning. I wrote a dissertation. And I brought it back to the people who taught me at Harvard, who were two legends in the philosophy department, John Rawls and Robert Nozick. And I talked to both of them about maybe becoming an academic philosopher. I said my other option was to be a journalist and a writer. They were both pretty nice about it, saying, you know, You’d make a good journalist and writer.

HUMANITIES: When you got back to the United States, you worked at a newspaper in Louisiana, and then, in 1978, took a job at Time magazine. You became national affairs editor, managing editor, and finally, editor. What was this whole experience like?

ISAACSON: It was a wonderful period. I was very lucky in the timing. You had great organizations, like Time, that could take writers from places such as Louisiana and train them, pay for them to go on campaign trails or to go to Eastern Europe to watch the crumbling of communism, all of the things I got to do in the 1980s. And you had these deep benches of journalistic talent, writers who were serious thinkers as well as good reporters. I got to watch Strobe Talbott write books about Russia as well as report on it.

On the other hand, there were only three or four major news magazines and newspapers and networks, and they served as gatekeepers. It was a little constricting, especially compared with today, when there are so many outlets for people to write and express themselves.

I particularly loved Time magazine, though, in the nineties. America needed a common ground, I felt. Also, I liked Henry Luce’s curiosity, his passion to explain everything from science to religion to world politics. And I have always felt that an educated citizen should try to know about all the different things happening.

HUMANITIES: Do you have a favorite story that you worked on at Time?

ISAACSON: I was particularly interested in two sets of stories. One was during the 1980s, watching the fall of communism. I got to spend some time in Gdańsk, where Lech Walesa was leading the rebellion in the shipyard; in Prague and Bratislava, watching people like Václav Havel and Alexander Dubček, who were the patron saints of freedom of expression in Czechoslovakia, as it was then called. And that inspired me. I learned that words and ideas have consequences, and can empower humans to be more free.

I saw also that technology could help, and certainly did when Czechoslovakia was going through its revolution. When I was in Prague, the hotel I stayed in was one of the few places that had satellite TV, and the kids would come after school to the hotel, so they could watch the music videos. At one point, I was in a hotel and the person who worked there said that some kids would love to use my room in the afternoon to watch satellite TV. I thought they’d be watching music videos when I came back, but instead they were watching CNN and what was happening in Berlin and Gdańsk.

The other great story I liked to cover was the digital revolution. I remember being fascinated by Andy Grove and the power of the microprocessor as well as the rise of the World Wide Web and Tim Berners-Lee and Marc Andreessen and what was happening with the Internet.

HUMANITIES: How did the methodology of journalism shape your book writing?

ISAACSON: When I was working on The Wise Men, with Evan Thomas, and then the biography of Henry Kissinger, I realized there were great reporters who were good at digging things out. And there were great scholars who were wonderful at going into archives and doing research. But often the two types didn’t overlap. Now, I might not have been as good a scholar as some and maybe not as good a reporter as some others, but I could do both. I could get Henry Kissinger and all the people who ever worked with him to talk, but I could also try to go through all of the archives, reading all the memos and other documents. This is my intersection, where you have to do good reporting, but also do as much academic research as possible.

HUMANITIES: I just watched an old C-SPAN interview with you that was taped after your Kissinger biography came out.

ISAACSON: When was that? Before I had grey hair?

HUMANITIES: You had floppy brown hair and the look of a preppy young reporter.

ISAACSON: Wow. I’ll have to go look at that.

HUMANITIES: You said that one thing you have in common with Kissinger is an interest in the personalities of history. What did you mean by that?

HUMANITIES: I was looking in the archives at Kissinger’s off-the-record briefings to reporters. And, on a shuttle mission in the Middle East, he said, “As a professor, I tended to think of history as run by impersonal forces. But when you see it in practice, you see the difference personalities make.” He was dealing with Golda Meir and Anwar Sadat, some great leaders, but he was probably thinking of himself as well.

I am fascinated by how personalities play off great forces. I saw Lech Walesa climb to the top of a wall in the Gdańsk shipyard, watching him as he gave his talk. The tide was shifting against communism, but there is also a real difference that a strong personality can make.

Time magazine always tried to tell the history of our time through the people who made it. There would be a person on the cover. This helped me understand how interesting people can be, whether you’re talking about a Gorbachev or an Andy Grove, especially when they ripple the surface of history.

HUMANITIES: What about personalities in Washington? What are some of the qualities that are key to succeeding as a political or media player in Washington these days?

ISAACSON: First of all, you have to have a deep understanding of what’s happening. Sometimes our leaders, whether they be corporate or government, don’t fully understand science or technology or business or economics. And instead they understand the politics or public relations of something they are trying to do.

I think it’s important to be collaborative. The book I’m writing now looks at how people worked together to invent things during the past fifty years, and how teamwork and collaboration tended to promote creativity. So, when I look at leaders in Washington I wonder, Who are the best at bringing people in, creating a collaborative creativity, as opposed to just being pure visionaries who impose their own mindsets on other people?

There’s always that tension between being collaborative and being stubbornly visionary. I’ve watched it in Steve Jobs, who was stubbornly visionary. Yet, somehow, he was able to create a great team around him. So, what’s the magic in being able to accomplish both tasks?

HUMANITIES: As the editor of Time from ‘96 to 2001, you oversaw the magazine during a time of incredible change in American journalism, especially in how news is distributed. What were some of the lessons you have taken from this upheaval in the last fifteen, twenty years?

ISAACSON: I think it’s wonderful that people now not only have access to thousands of times more information and that they can also be producers of opinion and content that they can distribute themselves. The only flaw is that the business models have not caught up with the technology.

As the Web allows everybody to make and consume content from anywhere, it has not been very good at supporting professional journalism and writing. I also worry that the opportunities I had as a young journalist are harder to come by in an era in which journalistic organizations don’t have as secure a set of revenue streams.

I hope eventually we will get to a system where digital journalism is supported not just by advertising dollars, but by revenue from readers, because you want to be more beholden to your readers than to your advertisers. And you’ll have a higher quality of journalism if and when we can get to a system where people are paying for it.

HUMANITIES: What is the Aspen Institute? And how does it fit into your career as a writer and journalist?

ISAACSON: The Aspen Institute was created sixty-five years ago. We’re an educational institute that tries to look at different issues that we face as a society. On education reform, for example, we’ve had programs that try to expose people to new ideas. We generally try to be nonideological and practical in helping people to become leaders and to deal with public policy issues. We also bring people together. The Nunn-Lugar reduction in nuclear arms between Russia and the United States was gestated at the Aspen Institute. In my books, I write about how people are more creative when they have a chance to collaborate and work together, and at the Aspen Institute we try to put that into practice.

HUMANITIES: Your four main biographies were about inventors and innovators: Henry Kissinger, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, and Steve Jobs. Aside from their obvious intellectual aptitude, were there any major personal qualities that you found in all four?

ISAACSON: They’re all very, very smart people. But, in life, you realize that smart people are a dime a dozen and often don’t amount to much. What really matters is being imaginative or creative and being able to think a little bit differently.

Henry Kissinger came up with a triangular balance between Russia, China, and the United States. Einstein questioned the opening of Newton’s Principia, in which Newton says that time marches along second by second, irrespective of how we observe it. Einstein asked, Well, how would we know that? How would we test that? How would you synchronize clocks and make sure that that’s the case?

What all of them had in common was that they rebelled slightly against received or conventional wisdom. And they were able to transform things. So, I always try to look at imagination, creativity, and innovation, as opposed to people who are just conventionally smart.

HUMANITIES: You worked for Time for more than twenty years, the Aspen Institute for over ten years. Would it be fair to say that you’re an organization man who writes about rebellious history makers?

ISAACSON: Yes. I like organizations because they tend to promote collaboration, creativity, people working together. I’m not as much of a loner as some of the people I’ve written about.

Einstein was the ultimate loner, both by personality and circumstance. When he was doing the general theory of relativity, which is probably the most beautiful theory in all of science, he’s at the Prussian Academy, where, as a Jew, he is being rejected by his colleagues. He has split up with his wife and is padding around his apartment alone. And yet, there he is, coming up with this amazing theory.

I’m certainly no Einstein. I love being part of an organization, part of groups, part of teams, where you can say, Hey, I’ve got this half-formed idea. Help me finish this sentence.

HUMANITIES: I have read two books about Ben Franklin in the last ten years, both of which I liked very much. One was by you and one was by Edmund Morgan. What is the difference between these types of books?

ISAACSON: Edmund Morgan is a glorious, wonderful writer and analyst. And he tries to get at the core of what Franklin’s character is about and does it, I think, in a magisterial way. He does it with deep analytical insight rather than traditional chronological narrative. I’m more of a conventional biographer. If you pick up page one of my book, you see Ben Franklin being born and raised. And if you look at the last page, you see the end of his life.

Mine is more of a narrative because I believe in narrative. It’s one way we organize the world. And you watch a kid, who’s a seventeen-year-old runaway, learning things, forming a club, a club of tradesman and leather-apron wearers in Philadelphia, they teach each other things, that makes him go on to be a pretty good scientist and then a diplomat.

I’m much more of a conventional, narrative, biographical writer. As Walker Percy would say, a storyteller.

HUMANITIES: For Einstein, you had to grapple with a large number of very technical subjects, and various language barriers, but still produced a generously sized and highly readable book about the most famous physicist of the twentieth century. How do you get so much work done, while also punching in at the office?

ISAACSON: I don’t watch TV. If you give up TV, it’s amazing how many hours there are between 7:00 p.m. and 1:00 a.m. in which you can do writing. More importantly, I work with a lot of people, Brian Greene, Murray Gell-Mann, people I knew who were tutoring me in physics.

When I tackled Einstein, I realized that science is totally beautiful. Nonscientists are often intimidated by it, but it’s not as hard when you can see the beauty in the tensor calculus that Einstein used for general relativity or the beauty in his thought experiments, which help him describe special relativity, gravity, and the curvature of the space-time fabric of the universe. Those are, to me, glorious, beautiful things. An outsider might think, Oh, that’s science and math. Isn’t that difficult? No, science and math can be really beautiful, especially if you have good people helping you learn it.

HUMANITIES: What part did the papers of Albert Einstein play in your work?

ISAACSON: With both Ben Franklin and Albert Einstein, I was lucky that their collected papers were about to reach a critical mass. Benjamin Franklin’s collected papers were being done at Yale. I went up to the Sterling Library at Yale and got to see the future volumes that were coming out. It was really the first time you could get a sense of the broad sweep of all his papers.

When I started on Einstein, I realized that there would soon be a major release of his papers. So, I held off doing the book until those papers were available. Diana Kormos Buchwald, the editor of the Einstein Papers out of Caltech, was enormously helpful. I spent a lot of time out there, as they were getting those papers ready.

It was the first time you could see fully the connections between Einstein’s personality and his scientific work. He was always questioning things, and you could see how this carried into the scientific ideas he was working on. We sometimes think of Einstein as this intimidating guy with a wild halo of hair. But, from his papers, you learn that he was spunky in his twenties.

He would mix the personal with the science. The greatest example is the letter he writes in 1905 to his friend Conrad Habicht. He says, “You frozen whale, you smoked, dried, canned piece of soul. . . . Why have you still not sent me your dissertation? Don’t you know I’m one of one and a half fellows who would read it with interest and pleasure?” If Habicht sends along his dissertation, Einstein says, “I promise you four papers in return.”

He’s a patent clerk at the time, but he’s written these four papers. And, he says, one of them involves a modification of the theory of space and time. And you go, Holy cow! There he is writing this letter to his friend, as if this is just a normal exchange with one of his buddies, but he is promising a new theory on the electrodynamics of moving bodies.

HUMANITIES: You are probably best known for your biography of Steve Jobs, who asked you to write it. How did you meet him? And why do you think he picked you?

ISAACSON: I first met Steve in January of 1984, when I was a young writer at Timemagazine and he was just coming out with the original Macintosh. He brought it to Timemagazine to show how awesome it was. I was the only writer at Time who wrote on a computer. The editors called me upstairs for this meeting with Steve Jobs so they could have at least one person there who actually used a computer.

I remember being mesmerized by Steve, who was about my age. He made us use a jeweler’s loupe to look at the bitmap display of the Macintosh and how it was able to create beautiful graphics on the screen. And he explained the flow of the curves and talked about the chamfers, using all that design lingo that he loved.

Halfway through the meeting, he told us that Time magazine sucked, which really surprised Henry Grunwald and some of the editors there. Jobs said, Because you should have made me man of the year last year and you didn’t. So, I saw both the passion for perfection and also that this passion made him a bit petulant or arrogant, at times.

But, I must admit, I totally liked him. I just thought, He’s really cool.

We kept in touch, especially when I became editor of Time and later head of CNN. I was his best friend for, you know, two or three days every year when he had a new product out and wanted it to be on the cover of Time or featured on CNN.

And then, when I became head of the Aspen Institute in, I guess it was 2003, he gave me a call. I invited him to speak at our Colorado campus. He said, Well, I don’t want to do a public speech, but let’s take a walk.

I had done Ben Franklin, and I was about to come out with Einstein. He said, Well, why don’t you do me next? And my first reaction was, Well, your humility hasn’t deepened much, since our very first meeting. Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, you.

But, later, somebody told me that he was fighting cancer. And I said, Well, he hadn’t mentioned it to me. Then this person said, Well, he was keeping it a secret, but he called you right after he was diagnosed.

I gave it some thought. Here was this guy who had transformed several industries: personal computers, music, cellphones, retail stores, digital animation. He was the American success story writ large. Somebody who had started a little company—with a friend down the street, in his parents’ garage—and turned it into the most valuable company, by market cap, ever in the history of the world.

It was an opportunity to see somebody up close, someone who is creative, a business leader, and has transformed industries. And we often don’t get up close that way—as Boswell was able to do with Dr. Johnson—with a person who is a leader in technology and industry. But I would have the opportunity to spend day after day with him, hours on end talking about what he had done.

HUMANITIES: Was Jobs successful because he was sometimes selfish and obnoxious? Would his success have been possible if he had not been?

ISAACSON: In writing a narrative, rather than a how-to book or an analysis book, you consciously step aside at times and let the reader make his or her own judgments. A key issue in the life of Steve Jobs is that he was, at times, a jerk. And you can find even stronger words to describe his way of being driven and rude and tough.

One of his oldest friends, who was on the original Macintosh team, said to me, The key question you have to answer is, did he have to be so mean? Steve Wozniak, who was the kid from down the street and the original partner, said, That’s the thing I never understood about Steve. Couldn’t he have treated people more like family?

My own personal belief is that you don’t have to be that tough. You don’t have to be mean in order to get things done and to get the best out of people. But I try to show all sides of Steve and let people draw their own conclusions.

When I asked Steve about it, he’d say things like, Look, you’re writing a biography. You’re writing about who I am. This happens to be who I am. I don’t think I have much time in this world, I’m driven. If somebody’s doing crappy work, I’m going to just tell him to his face that’s the case. And other people might try to sugarcoat things. Back east, where you come from, maybe people treat other people with velvet gloves, but I’m just a kid trying hard to create amazing products. And I’m going to be who I am.

Is such behavior necessary to becoming an effective leader? When people ask me this, I suggest they read Ben Franklin. He was the nicest, most collegial guy. He was so friendly that he was accused of being insinuating. Ben Franklin was a great leader because he brought people together and made them feel more creative as a group than they felt separately. Steve was a great leader too. He drove people crazy and drove them to distraction, but he also drove them to do things that they didn’t know they had the capacity to do.

I don’t think there’s a simple formula for how to be a great leader. This is good, because if there were a simple formula, you would not need biographers to say, here’s how Einstein did it, here’s how Franklin did it, here’s how Jobs did it, here’s how Kissinger did it. Biographies are not how-to manuals or seven-steps-to-success books. They’re about flesh-and-blood people who were able to make a dent in the universe, to use Steve’s phrase.

HUMANITIES: What is your next book project? And how are you using the Internet to write it?

ISAACSON: My current project, titled The Innovators, is about collaboration and how that created the Internet, the computer, the microchip, and the other components that led to the digital revolution. I wanted to get back to what Evan Thomas and I did with The Wise Men, which is to look at how people in groups can become creative.

We biographers sometimes distort history by making it look like it was only single individuals who had the lightbulb moments and came up with new ideas. My own instinct, from having read history and having lived amid a lot of transformative events, is that creativity tends to come from people bouncing ideas around together. And so I wanted my next book to show how teamwork and collaboration actually happen.

HUMANITIES: We look forward to it. Thanks for talking with us.

*This article was updated on July 8, 2014, to clarify a date in the text.