Scene: Bloomsbury, London, on or about December 1910

Dramatis Personae: PAINTERS, DESIGNERS, NOVELISTS, PHILOSOPHERS, ART CRITICS, PUBLISHERS, ARTISANS, HOAXERS, a POET-SOLDIER, an ECONOMIST, an EMINENT BIOGRAPHER, and SUNDRY YANKEE FOLK OF INDEPENDENT TASTE

Exeunt [VICTORIANS]. Enter, with a flourish, [BLOOMSBERRIES].

Bloomsbury, the group of innovative writers and artists, came out of its embryonic phase around 1910 as the Victorian era finally expired with the funeral of Edward VII. Its young mix of writers, thinkers, and artists stood at the vanguard of a shift in manners away from nineteenth-century formality and reticence and toward twentieth-century candor and playfulness. Male and female, mostly in their twenties, the Bloomsbury lot addressed each other by their first names, spoke openly about sexual matters, and, till the wee hours of the morning, reflected on how to spend their lives. “A Room of Their Own: The Bloomsbury Artists in American Collections,” an exhibition that opened in December 2008 at the Nasher Museum of Art in Durham, North Carolina, will run through April 5, 2009, before touring the country over the next couple of years and making stops at five other museums.

Fascinated by the difference between the world of appearances and the world of reality, in the visual and literary arts, the Bloomsberries (as they were sometimes called) experimented with brush and pen to express above all the subjective qualities of their work. For the painters, who opened themselves up to the currents swirling around on the Continent since the final days of Impressionism, this translated into an emphasis on line, mass, contour, and the rhythms they create.

If any one work by the Bloomsbury painters sums up adequately the era’s avant-garde break with London’s Victorian taste in art, and the influence of the French Post-Impressionists on British artists, it would be Vanessa Bell’s 1915 oil on canvas of Mary St. John Hutchinson. With arched eyebrow, lips slightly pursed, and cool self- assurance, Mrs. Hutchinson sits noticing something to her left, and the viewer, disarmed at first perhaps by the flatness of the composition and the coarse brushwork, feels as much as sees the various tones of the few colors in the portrait—ochre, green, and pink, and, where the whites of the eyes should be, teal. The work broke all the reigning conventions in British painting. Treatment of subject, use of line and color, lack of shadowing, and the solidness of the background in relation to the figure are all in sync with the modernist modes that had been in style on the Continent, most notably in France.

This English modernism struck a chord with American collectors who shared Bloomsbury’s rebellious streak. They reveled in the rejection of Victorian rigidities and embraced Bloomsbury’s lightheartedness. Inspired by Charleston farmhouse (itself an embodiment of Bloomsbury art and design sensibilities) and the ceramics and furniture produced by a Bloomsbury offshoot, the Omega Workshops, some Americans, before actually having the money in hand to collect, started copying the effects of Bloomsbury in their own homes, often painting their own interiors in the same unorthodox, highly decorative way.

If Bloomsbury had been an art department, Roger Fry would have been faculty chairman. Fellow art critic Clive Bell called him the most open-minded person he had ever met. Painter, curator, and instigator, Fry studied the sciences at Cambridge in the 1880s, developing a habit of skepticism that would serve him well as he guided painters Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant toward modernism in the years leading up to World War I. While at Cambridge, Fry came under the influence of philosopher G. E. Moore, who helped him and subsequently the Bloomsbury painters develop their aesthetic sense. In his best known work, Principia Ethica, Moore posed the question “What things are good or ends in themselves?” The members of Bloomsbury discussed this endlessly, concurring with Moore, that “by far the most valuable things, which we know or can imagine, are certain states of consciousness, which may be roughly described as the pleasures of human intercourse and the enjoyment of beautiful objects. . . . It is the ultimate and fundamental truth of moral philosophy. . . . Personal affections and aesthetic enjoyments include all the greatest, and by far the greatest goods we can imagine.”

A disciple of Bernard Berenson, critic and expert on Italian Renaissance painting, Fry became known to Americans first as a connoisseur. He was curator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1906–1907. The only piece of his that sold to an American during his lifetime was a still life, The Blue Bowl, purchased by a museum director in 1924. The American interest in collecting Bloomsbury painters, however, blossomed outside of the institutional art world. And the art was placed in America’s warmest domestic setting: the living room.

Bloomsbury itself had more than a little of the open house spirit. Personal affections and aesthetic enjoyments were the constant fare at Thursday and Friday night get-togethers organized in London’s then-unfashionable Bloomsbury neighborhood. Starting in 1905, sisters Vanessa and Virginia Stephen welcomed an array of original thinkers to their home at 46 Gordon Square for hours-long discussions, which could become contentious. “What exactly do you mean” was a frequent, intentionally probing question. Camaraderie was all well and good, but truth, accuracy, and sound reasoning counted for more. Both in Bloomsbury and later within the brightly painted interiors of Charleston farmhouse, in Sussex, southeast of London, scintillating conversation, friendship and romance, a commitment to the arts, and the maintenance of congenial surroundings conducive to creativity reigned supreme.

In addition to Virginia (later Virginia Woolf) and Vanessa and critic Clive Bell, who would marry and live at Charleston farmhouse, the conversational soirées regularly included economist John Maynard Keynes, painter Grant, Berenson, novelist E. M. Forster, poet Rupert Brooke, writer and later publisher Leonard Woolf, and Eminent Victorians author Lytton Strachey.

Vanessa and Virginia’s brother Adrian, who like Fry had been a member of the Cambridge Apostles, a secret intellectual society, was often in attendance and took part in the Dreadnought Hoax. Dressed as a visiting delegation from Abyssinia, Bloomsbury hoaxsters requested and received permission to board the HMS Dreadnought for an official visit. Repeating made-up remarks of approval and amazement—“Bunga! Bunga!”—while on board the state-of-the-art battleship, the costumed troupe pulled off the ruse, much to the embarrassment of British government officials. For all their aesthetics and philosophy, teasing was also a key part of Bloomsbury’s modus vivendi.

The British public may have wished to give Fry a good caning, though, after he organized the first Post-Impressionist Exhibition at Grafton Gallery in 1910. The works on display by Picasso, Cézanne, Matisse, Gauguin, van Gogh, and Manet, among others, met with derision. These reactions were doubtlessly driven by a fear of the new. The colors, the public thought, were garish, the compositions childish, and some of the subject matter shocking.

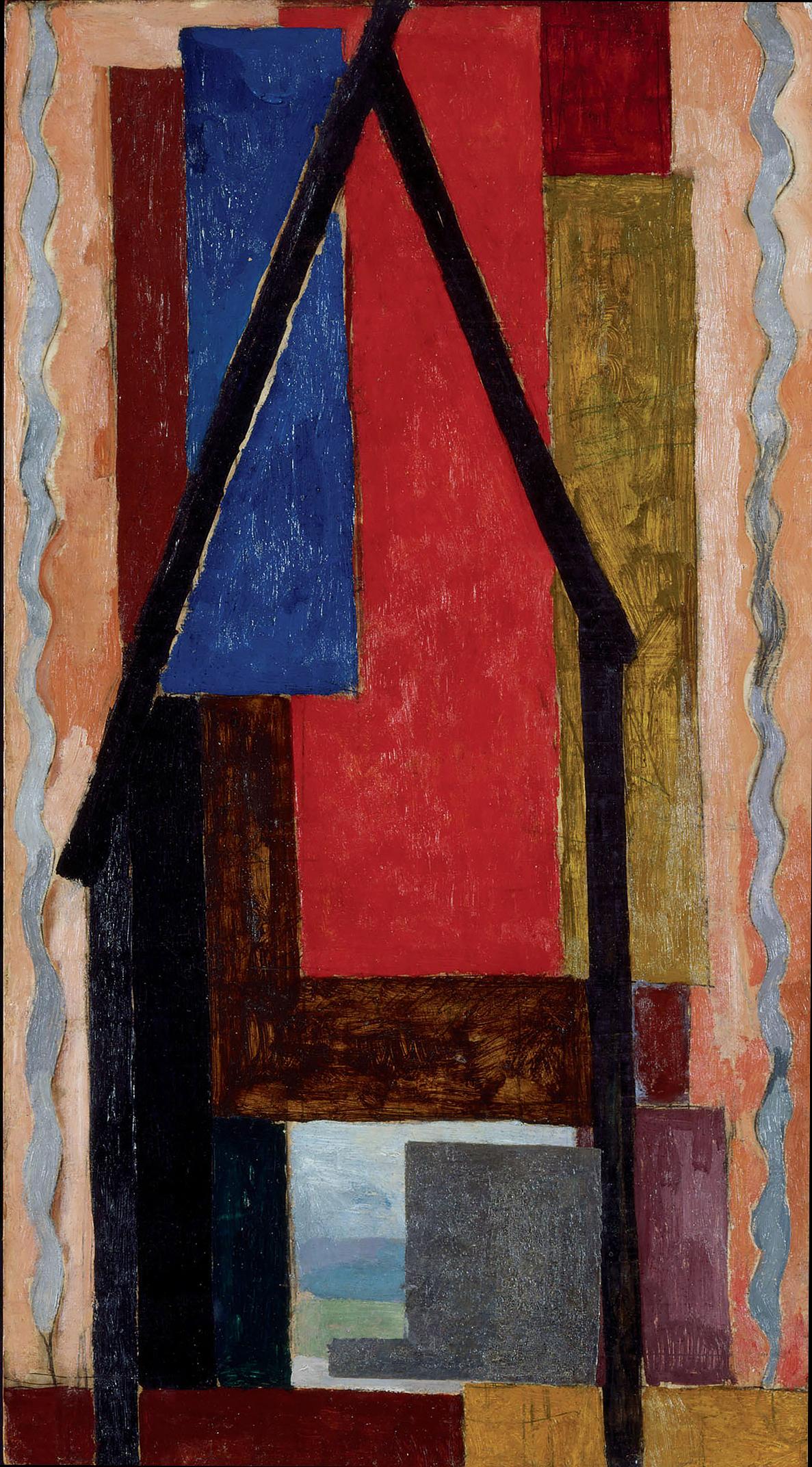

Influenced by paintings they had seen in France, Fry, Grant, and Bell experimented early on with cubism and abstraction, which helped the latter two immensely in their designing and painting of objects, especially ceramics, produced by the Omega Workshops from about 1913 to 1916. Fry had also convinced the traditionally trained Grant to lighten the colors of his palette and Bell to express her feelings more completely. The result was an outpouring of their creative energy. Bell wrote, “That autumn of 1910 is to me a time when everything seemed springing to new life—a time when all was a sizzle of excitement, new relationships, new ideas, different and intense emotions seemed to be crowding into one’s life.” She later added, “Perhaps I did not realize how much Roger was at the center of it all.”

Bloomsbury’s anti-Victorian revolt had, in fact, as much to do with getting back to Fry’s perceptions of the great traditions in art as it did with youthful rebellion. In France, the painter Simon Bussy acted as cicerone for the group, introducing them to French artists and reaffirming the necessity to study the old masters. Grant began looking into works by Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, and Poussin. Another Victorian ideal the group chose to keep was undying loyalty to friends, something Vanessa and Virginia learned from their father, writer Leslie Stephen.

Yet another was the Victorian veneration of comfortable home life but with the subsequent Bloomsbury love of color, brightening what they saw as stuffy and stodgy in the homes of their youth. Fry felt, moreover, that nineteenth-century British artists in general, and Victorian painters in particular, had lost their way by becoming preoccupied with attempts at highly detailed and, in some cases, photographically accurate representations of reality. What he advocated but never fully achieved in his own paintings was the presentation of “significant form,” a term he and Bell employed but never quite defined.

The French painters Fry admired had been trending toward a new aesthetic for over two decades. But these artists, unlike the Impressionists, had little in common as a group except for the fact that they were all influenced in some way by Impressionism’s ideals; they passed through the era, learning from it and reacting to it while continuing to develop their own visions. Gauguin had been vibrantly imbuing his work with desire and emotion; Matisse pared his down to a harmonious interplay of line and rhythm; and Cézanne had been looking back to the masterpieces of primitive and epic works in order to bring about a monumental effect. Fry’s study of their painting taught him a new language of design, which he wanted to try out himself and convince other British painters to take up. Clive Bell was arriving at similar conclusions. “The starting-point for all systems of aesthetics,” he wrote, “must be the personal experience of a peculiar emotion. The objects that provoke this emotion we call works of art.”

The second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, in 1912, was a chance for Fry, Bell, and Grant to show their work alongside their Gallic mentors. Bell had been trained at the tradition-bound Slade School of Fine Art but was by 1905 liberated from her teachers’ constraints, and her still lifes, portraits, and landscapes began to distill the essence of what she had soaked up in various galleries around London and, specifically, at the Grafton Gallery in 1910. Among some of her most powerful works from this period are Landscape with Haystack, Asheham; Lytton Stratchey; and Omega Paintpots. In the first, by placing a haystack at the center of the composition, she pays tribute to Monet while employing technique from Cézanne and Matisse. In the second, in the manner of Cézanne, she molds the contours of background to accommodate and frame the figure, Lytton Strachey, who with his astringent writing style and non-doctrinaire approach to living and loving was a favorite subject of the Bloomsbury painters. (Strachey would sometimes “express his individuality,” as the euphemism of the day put it, with Rupert Brooke during seaside getaways.) And in Omega Paintpots Bell seems to be guided again by the hand of Aix-en-Provence’s favorite son, Monsieur Cézanne, as she adjusts the perspective, depriving the composition, perhaps, of its three-dimensional reality, in order to reveal an inner logic in the design.

In the exhibit at the Nasher, some of Bell’s best-known portraits, those of her sister, novelist Virginia Woolf, and of Virginia’s husband and publishing partner, Leonard, welcome visitors as they enter the first of three rooms of the show. Visitors soon realize the Bloomsberries painted what was most familiar to them— scenes of Charleston farmhouse, the surrounding landscape on Sussex downs, and many of the members of the group—but their many manners may be heretofore unfamiliar to most casual admirers. Bell, for example, treats her sister with rapid brushwork and bold composition but leaves her familiar visage nearly featureless. The contours of Virginia’s armchair frame her entirely, the rest of the room dissolving into an undifferentiated background of green, purple, and grayish streaks. Bell presents Leonard Woolf in a much more straightforward manner, at work, typing at his desk, with a dog lying contentedly nearby. But manner here, as elsewhere, is everything. Bell again employs her highly personal, expressive brushwork, treating shadows and shapes in their own right. The work of Leonard Woolf in the exhibit is a study for the finished painting, but even so, her fondness for him shows through clearly enough, as do her hard feelings toward Mrs. Hutchinson in the portrait of her—the patron of the arts having had an affair with Vanessa’s husband, Clive. One American collector, reflecting on her own collection’s emphasis on Bloomsbury portraiture, has said, “That’s what they did so well, because they knew each other, and the portraits are about what they felt.”

Bell’s work for the Hogarth Press is also much in evidence in the Nasher show. She designed book covers for many of the volumes published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf, including Virginia’s To the Lighthouse. The press printed the works of authors it wanted to get into readers’ hands, including T. S. Eliot, Sigmund Freud, and E. M. Forster. Books published by Hogarth were meant, of course, to be read rather than appreciated for aesthetic value. Bell’s strong sense of design, however, revolutionized the design of book covers, persuading publishers that you can tell a book by its cover.

The Bloomsbury painters have sometimes been grouped under the flip Wildean banner of Art for Art’s Sake, but in the case of Bell, and in all likelihood the other painters as well, this was inaccurate. Like Fry, the formalist of the group, she was guided by her own continually developing aesthetic sensibility, which took her in artistically diverse directions.

Further on in the Nasher show, for example, is a pointillist color lithograph she did for Royal Dutch Shell, several abstract pieces, painted shutters from Charleston, and jaunty, Matisse-like fabric designs done for the Omega Workshops. Another American collector, Susan Chaires, has said, “You could put virtually any Vanessa Bell up on wallpaper, and it would just be fabulous. I love that tension between the colors and the highly decorative background where the colors talk to each other. That’s the way it is at Charleston.”

There was the couple who had decorated their apartment in the 1960s with Pop Art but in the 1980s opted for Bloomsbury paintings because of their “domestic scale, color, and light.” American painter Jasper Johns has long collected ceramics and furniture from the Omega Workshops, and yet another American collector has said her interest derives from “Charleston as a community of artists with all their personal stuff, but with a true commitment to this aesthetic, to making the functional space beautiful.” Fry adapted the idea of “animal spirits” from Maynard Keynes in describing the motivations and behaviors—the psychology—of collectors. In the same way that Keynes employed the term to describe investors, Fry would write of a snob, classicist, or herd mentality to describe the behavior of collectors. American collectors have been too self-conscious for Fry’s categories. Still others, such as Ms. Chaires, see something to admire in the work ethic of the Bloomsbury painters: “I admire the fact that . . . they were all working all the time. . . . I don’t know if this is a uniquely American perspective, but a lot of Americans tend to be real workaholics. We can’t rely on being a duchess to get ahead in life, we have to work.”

The Nasher exhibit shows, too, how differently painters in the group treated the same subject at the same time. Both Fry and Grant painted Winifred Gill, a contributor to the Omega Workshops, seated by the edge of a pool, reading, her shrouded, turned-down head and upper body partially or entirely reflected on the surface of the water, which is also punctuated with about a half dozen lily pads. By placing the paintings side by side, the exhibit reveals in both compositions the importance of the ledge of the pool in its anchoring role of dividing subject from reflection. However, Fry’s treatment of each element—the lawn and part of the house in the background, Gill’s scarf, her book, her face, even as it appears in the pool—is well delineated, while in Grant’s, they are presented in rapid brushwork and flattened out. In the first, the canvas, more in line with tradition, is a window (the viewer peers into the picture as through an open window), in the second, the canvas is more screen-like, comprising patches of color. The two couldn’t be more different in manner.

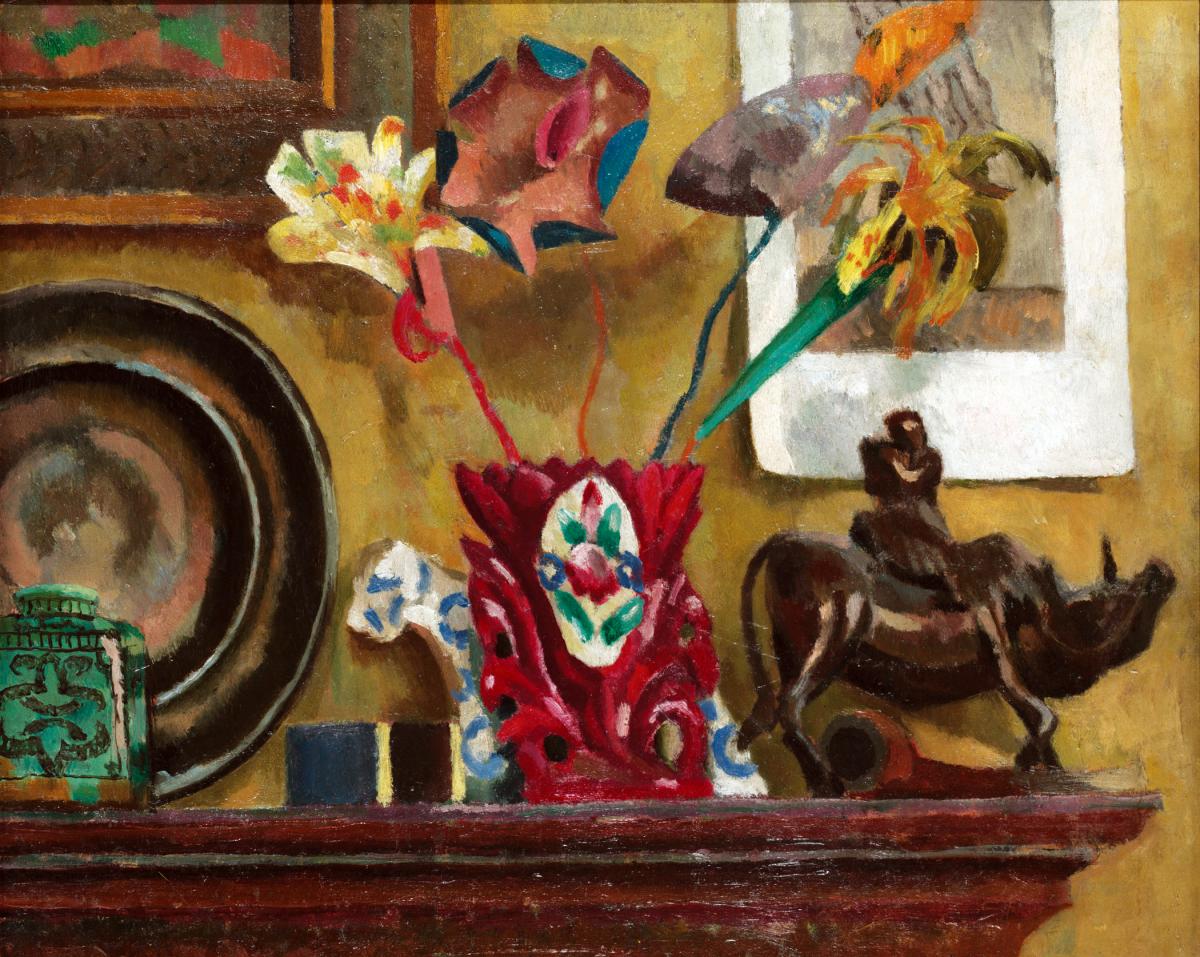

Duncan Grant certainly had a good work ethic. He made designs for ceramics and fabric, large-scale paintings that embellished the Queen Mary, designs as well for bookmarks, bookplates, scenery for an opera, and like Vanessa, a travel poster for Shell Oil encouraging motorists to tour Britain. At Charleston farmhouse, his brush decorated bedsteads, fire screens, and many other nooks and crannies throughout the demesne. Virginia Woolf recalls him coming round to Gordon Square asking for pieces of broken china to paint. Society hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell once said to him, “After all, you are a lucky dog to have your Life simplified by the passion for Paints. . . . Other forms of existence are so exhausting & so unsatisfactory.”

Dora Carrington, known simply as Carrington, is the Bloomsbury artist with fewest works in the traveling exhibit, but she has been the most visible in recent years, since the 1995 Emma Thompson movie about her life. As Carrington biographer Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina points out in the catalog to the Nasher show, Carrington’s “life resonated with so many women I had known in the 1960s and ’70s. As with my generation, there was a history of resistance to a terrible war; a break from the terrible social and domestic restrictions of their parents’ generation; a fierce desire to find a new communal and creative way of life; a dedication to her work.” Carrington, who had trained at the Slade, “was the first woman there to lop off her hair as well as her first name.” She wound up in Omega Workshops, which had been created to give artists work several days a week in the decorative arts, but was very introverted. She met Lytton Strachey and slowly entered the realm of Bloomsbury.

The Nasher show ends with Carrington’s Begonias, which hangs near the exit of the exhibit’s final room. The oil on canvas is a lovely composition that toys with our perspective and perceptions—a seemingly joyful presentation of the power of design, both nature’s and our own. In its brushwork, vibrant color, and exuberant treatment of flora, it’s a poignant tribute to van Gogh. Painted five years before she took her own life, however, and while she was the companion of and in love with Strachey, it conceals perhaps as much as it reveals about her frame of mind.

But that so much of the Bloomsbury painters’ work remains in American collections is a lasting tribute to one of the group’s most basic and commonly held ideas: that art can turn a vision into a design that can in turn connect—“only connect”—with people’s lives. Bunga! Bunga!