Walking through the sloping grounds of the Shelburne Museum in Vermont, its thirty-five historic buildings moved from various parts of New England and New York, I feel I’m on familiar ground. This is obviously one of those colonial village experiences, where anachronistically dressed interpreters will spin wool and make candy, showing me what it was like to live in the 1700s (not very pleasant, I always conclude).

But the more I see, the more I feel as if I’ve stepped into some kind of surrealist vision of a historic village. The buildings comprise a wide range of time periods and architectural styles, from the lovingly restored round barn and nineteenth-century general store and apothecary, to the giant steamship Ticonderoga, beached in the middle of the Day-Glo green spring landscape next to a real lighthouse, complete with a faux rocky shoal resting on a grassy bank dotted with lilacs. Cheek-by-jowl with the lighthouse is a miniaturized Greek Revival mansion, white pillars gleaming in the sun. And just when I’ve been lulled into a rural New England reverie, the Adam Kalkin house, constructed from three metal transoceanic shipping containers and a pair of huge garage doors, beckons from one end of the museum’s grounds, a modern interpretation of American living.

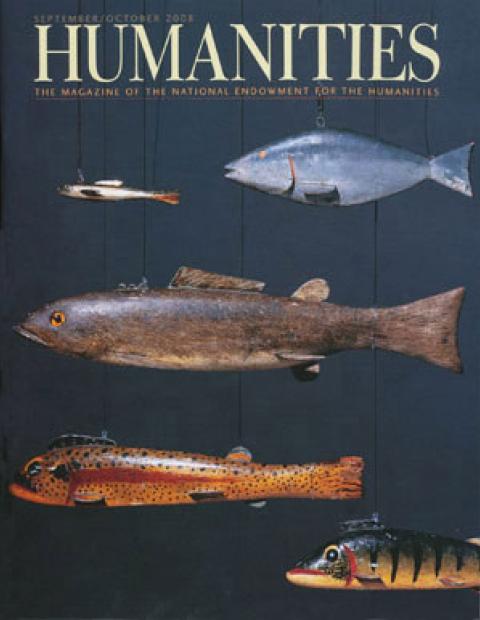

It’s an odd and heady experience, made even odder when I start to encounter the bewitching variety of art and decorative objects housed in the Shelburne’s buildings: antique hatboxes; four hundred traveling inkwells; snuffboxes; vintage barber tools; dolls and doll clothes; paintings by Degas and Goya; trophy heads of bear, moose, and other big game, and paintings and photographs of big game from the American West; an extensive collection of stagecoaches; intricately carved and painted carousel animals; and famously, the most comprehensive collection of tobacconist’s figures and American folk art sculpture and painting in the world.

And then there are the well-informed guides who wait in each building, willing to tell you all about the treasures within, not a candy-maker in sight. It takes me a minute to get it: I’m in a world-class art museum disguised as a historic village.

The Shelburne Museum, in all its surreal glory, is the legacy and brainchild of Electra Havemeyer Webb, an heiress and wealthy collector who helped create the Colonial Revival and ignite interest in American folk art and decorative objects that had never before been considered art. The glorious juxtapositioning of seemingly disparate items at the Shelburne came out of Webb’s own reimagining of what “art” was and what kinds of art and everyday items could be considered beautiful.

Webb was the daughter of Henry O. Havemeyer, the head of the American Sugar Refining Company, and Louisine Havemeyer a childhood friend of Mary Cassatt and a champion of European painting. Webb learned about collecting from her parents, but she became very much her own woman and her own kind of collector.

She bought her first piece of fine art, a Goya, when she was eighteen. Her second purchase was a “cigar store Indian girl”—now more properly referred to as a “tobacconist’s figure”—that she purchased for $15 and which horrified her mother when it was brought to the family’s country home in Connecticut. It was only the first in what would be a long list of revolutionary purchases.

After her 1910 marriage to James Watson Webb, a Vanderbilt heir whose parents had a home in Shelburne, she began to collect in earnest, furnishing the couple’s own homes in Manhattan, Long Island, and Vermont with American folk art items and oddities.

It’s hard to imagine now just how outré her tastes were for the times. But she found something elemental and pleasing in the Americana her own mother referred to as “trash.” Later, Webb would describe folk art as “the self-expression which has welled up from the hearts and hands of the people. . . . Their work can be exquisitely wrought or it can be crude. . . . We must sense in all of the work properly identified as folk art the strong desire on the part of the people to create something of beauty.”

It was beauty, always, that she looked for, according to the Shelburne’s senior curator, Jean Burks, whether it was a bit of English pottery, a fancifully dressed French doll, or a Greek Revival house.

She kept buying, working with galleries in New York and following her own nose, and soon her collections would spill out of the family’s homes, into barns, and onto tennis courts, a foreshadowing of the Shelburne Museum’s sprawling footprint. The museum itself started with a collection of magnificent stagecoaches owned by Webb’s in-laws and incorporated in 1947 on an eight-acre parcel of land in Shelburne. She carefully began moving historic buildings from various parts of New York and New England to the site and began exhibiting the objects she had collected, along with household items and examples of folk art sent to her by New Englanders.

The museum has grown steadily since Webb’s death in 1960, but it is still profoundly influenced by her tastes and her appreciation for American folk art. Museum staff have overseen the acquisition and display of many new items and collections, including a Canadian schoolteacher’s collection of two thousand trivets, along with additional pieces of Spode and Mocha Ware pottery, quilts, paintings, and other treasures.

“I always try to think to myself, ‘What would Electra be collecting today?’” says Burks.

Burks says Webb was interested in “color, pattern, and scale” and attracted to objects that displayed an innovative use of all three. This interest is on full display in the museum’s collection of eight hundred American quilts and bed coverings, many made in New England and representing a wide range of styles and historical periods. The leaf-like upright wooden cases, which swing out to display rotating selections from the museum’s collection, were invented by Webb and exemplify her approach to household objects that had not previously been deemed worthy of museum treatment.

“She was the first to say you don’t have to drape quilts over beds in order to show them,” says Burks. “She said, ‘No, they’re art. You can hang them up on the wall.’”

The quilts range from simple geometric patterns to elaborate floral designs that tie into a special exhibition of contemporary floral quilts called “Quilts in Bloom: A Bouquet of Textile Art,” on view until October 26. The highly stylized patchwork floral motifs of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries give way to the hyperrealistic, almost photographic textile renderings of poppies and pansies and dandelions included in the special exhibition, none of which is likely ever to see the top of a mattress.

Nearby are Webb’s extensive collections of hatboxes and bandboxes, strictly utilitarian objects that were used to carry and store hats and other items. Decorated with beautifully patterned papers in shades of blue, the boxes evolved and became a fad of sorts between 1825 and 1850, as Americans started traveling on steam locomotives.

The papers used on the lightweight wooden boxes were part of the allure for Webb; she used them to cover the walls in her Westbury, Long Island, home, and some of those panels are exhibited alongside the actual boxes.

Though it’s known for its eighteenth- and nineteenth-century folk art, the Shelburne is trying to help museumgoers make the connection between the innovative design of yesteryear and the next new thing.

A 2008 special exhibit called “Design Rewind: The Origins of Innovation,” curated by Kory Rogers, highlights the connections between contemporary consumer products and items from the museum’s permanent collection. The exhibit pairs an antique bandbox with a suitcase designed by Japanese designer Hideo Wakamatsu and a 2008 camera phone with a 1850s miniature portrait, painted on ivory and meant to be carried in the pocket. What the exhibit made clear to me was that human beings have always incorporated whimsy into our utilitarian objects, whether the scrolls on an eighteenth-century chair or the pattern on a twenty-first-century kitchen trivet.

“It shows that design is on a continuum,” says Rogers. “There’s a lineage to all of these contemporary things.”

Museum director Stephan Jost says that he hopes to continue to make that connection for those who come to the museum, many of whom come for the folk art, but leave thinking about twenty-first-century design trends.

“I want people who love antiques to fall in love with contemporary design,” he says. It’s an idea that he thinks Electra Havemeyer Webb would have echoed. “Electra used ‘Ye Olde Country Village’ as a way to show her art collection,” he says. “Because you couldn’t show folk art sixty years ago.” It’s important to remember, he says, that she was a visionary in her embrace of American art.

There is a certain sneakiness to some of the museum’s collection. An exhibition of restored carousel animals made me contemplate the influence of European artisans on the American folk art tradition. I found myself thinking about the contributions of wealthy hunting families like the Webbs to the conservation movement as I communed with big game in the Beach Lodge, a replicated Adirondack hunting lodge containing an extensive collection of taxidermy. Next door, the Beach Gallery displays an exhaustive collection of paintings and photographs of big game in the American West. The visual images, by painters such as Carl Rungius, function more as trophies than as paintings of the natural landscape. The bear and bison stare out resolutely from their frames, evidence of the courage of the big game hunters, like Electra Webb herself, who both killed them with glee and protected their habitats.

Like most American museums founded by wealthy collectors, the Shelburne is, of course, a reflection of the ways in which financially successful industrialist families have shaped America’s cultural history. The influence of families like the Havemeyers and the Webbs is perhaps best on display at the Electra Havemeyer Webb Memorial Building. The Greek Revival structure, based on a house in Orwell, Vermont, contains the recreated interiors of Webb’s 1930s Park Avenue apartment, complete with the stunning though small collection of European paintings she inherited from her parents. Most of the Havemeyers’ collection of more than five hundred paintings went to the Metropolitan Museum, but what was left to their daughter is truly remarkable.

It would be a thrill to see any one of the works by Monet, Manet, Degas, Cassatt, or Goya, but altogether in the cozy faux apartment rather than gracing a cavernous gallery, they’re almost too much to take in. Almost. After a few minutes of looking at some of the world’s most priceless paintings, I realize I’m seeing them for the first time as everyday objects, as decorative items chosen for, yes, sheer mastery, but also for what they add to an interior, what they say about the people who live there.

There’s something wonderfully voyeuristic about seeing these famous works the way they were initially displayed in America, in private homes, as evidence of the owners’ fashionable European interests. In the absinthe-green guest room, a series of Degas’s ballerinas, hung with a set of drawings and paintings by Mary Cassatt, are positively bewitching. The somewhat generic mid-century dining room is made extraordinary-–and extraordinarily serene and comfortable—by Monet’s The Drawbridge, Amsterdam, the first Monet displayed in the United States, and other Impressionist masterpieces.

It’s this sense of the beauty to be found in the things with which we choose to surround ourselves that lingers as I leave the Webb family’s gracious “home.” But before I go, I find myself wandering through the weird landscape of the Shelburne Museum one more time and making my way to the quilts. I’m craving the human stories behind these bits of Americana, and I can’t help thinking that this was what drew Webb to the extraordinary work of the unsung men and women who made stagecoaches, drinking vessels, bed coverings, and hatboxes as beautiful as they could possibly be, who carved and hammered and sewed their life stories into everything they made.

I linger for a few minutes in front of a white-and-red embroidered quilt made by Regina Schnauber of Redwood, New York, in 1888. A plaque explains that Schnauber was discouraged from marrying by her parents, who wanted her to care for them in their old age. She stayed with them, but had an affair with a married cattle dealer and gave birth to a daughter. Amongst the images of animals, flowers, and people carefully embroidered on the quilt, she chose to include only one square of text.

The words? “Into Our Lives Some Rain Must Fall.”

In the days after my visit, it’s Regina Schnauber I keep thinking of, of the many hours she spent on that quilt, and of her desire, her need, to share some of her pain with the world. As Electra Havemeyer Webb knew very well, if that’s not art, I don’t know what is.