“Listen my children and you shall hear, / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.”

Just as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow introduced generations of students to the story of the American Revolution using meter and rhyme, so can today's teachers use visual art to convey important lessons about American history and culture.

To this end, the National Endowment for the Humanities is piloting a program to bring high-quality reproductions of forty works of American art into classrooms and libraries in every state of the union. Cosponsored by the American Library Association, Picturing America will survey a variety of subjects and styles from Anasazi pots (c. 1100) to modern architecture, from eighteenth-century portraits to contemporary sculpture. These large laminated reproductions will be accompanied by a teachers guide containing background essays and lesson suggestions for each work of art as they are sent out to 1,557 schools this fall.

"Picturing America tells the story of the United States through forty of its masterpieces," says NEH Chairman Bruce Cole. "We are using great art to tell the story of our nation from colonial times to the twentieth century. Our goal is to reintroduce American art into the classroom, to give kids who never see art at home or in museums the chance to see this art. We want to give young people a sense that art is important, that it can play a role in their lives, as much as music or sports."

The selected works of art are accessible yet challenging, suitable for kindergartners and high school students alike. Placed side by side or around the classroom, they can be grouped to show many perspectives on American history.

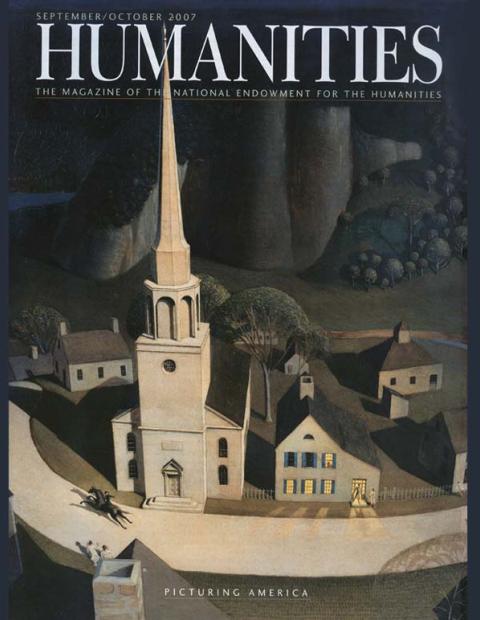

John Singleton Copley's 1768 portrait of Paul Revere reveals an artisan, not a revolutionary. It was painted seven years before Revere warned colonists of the impending British attack—the scene depicted in Grant Wood's twentieth-century painting inspired by Longfellow's 1860 poem. Although Revere is the subject of both paintings, each one tells a different piece of the American story.

Copley, one of the most distinguished portrait artists of the colonial era, chose to paint Revere as a successful silversmith. The portrait captures a craftsman proud of his work, surrounded by his tools, and holding one of his teapots, which he is about to engrave. The image is emblematic of the commercial spirit of American society and the ambitions of its craftsmen.

Wood's 1931 painting, The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, provides a mythical interpretation of Revere as he makes his famous ride through the New England countryside. In the artist's playful style, the setting looks like a toy village, complete with church and steeple and surrounding houses of simple geometric shapes. Painted during the Great Depression, Wood wanted to convey an image that linked America with its past and, as he said, save those “bits of American folklore that are too good to lose.”

“These iconic American images can bring history alive for students,” says Barbara Bays, an NEH senior program officer who helped develop the syllabus and select the works of art. “Take the Revere portrait by Copley or the Gilbert Stuart of Washington, for example. Students can see these as real people painted by artists of their time. It makes history a tangible thing.”

In Stuart's Lansdowne portrait of George Washington, 1796, the artist presents a statesman, placing him in the classical pose of an orator, before a background of draperies, columns, and a glimpse of landscape. It is a picture worthy of a king, but not of a king, mirroring the larger debate during the founding over what form of government the United States should adopt.

“The painting was conceived in the grand style that was usually used to depict nobility—and it conveys Washington's noble character and personal dignity,” says Cole. “But the details of the painting are distinctly American and democratic.”

Washington wears a simple black suit and stands by a table displaying volumes of The Federalist and the Journal of Congress, which refer to the foundations of the government and Washington's role as president. The Great Seal of the United States is on the back of the chair.

Another painting of Washington shows him as a general, twenty years earlier, in the midst of a surprise attack on Hessian troops. In the enormous—twelve by twenty-one feet—1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, German-born Emanuel Leutze presents a pivotal moment of the American Revolution, when Washington's attack helped turn the tide of the war. Leutze depicts him standing near the prow of a boat crowded with his soldiers as it navigates the turbulent waters of the Delaware River on Christmas night 1776. The viewer can sense Washington's determination and courage in facing battle; a different man at a different moment than the one in the Stuart portrait.

The details also have much to say. The boat shows thirteen soldiers, representing the thirteen colonies. The men are dressed in rags, suggestive of the poor condition of the army, which needed money badly. And what to make of the fact that one of the soldiers is black? Leutze, it so happens, was a passionate abolitionist.

Bays notes that the various works of art were chosen to represent “great art from different time periods. We looked for art that was layered and rich and demonstrated a lot of different ideas,” she says. “We chose images that can be paired to bring out more information about the subject matter or grouped thematically. And we chose a variety of media—paintings in watercolor, oil, tempura, sculpture, architecture, photography, pottery and baskets, quilts, and stained glass.”

Picturing America also includes work by Thomas Cole, John James Audubon, and Albert Bierstadt, who created striking vistas of the American landscape and the opening of the American West. Picturing America features great artists of the late nineteenth century: Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, and James Whistler, all known for their realism, and Mary Cassatt, an American Impressionist who trained in Paris. The early twentieth century, as the nation industrialized, is represented by Edward Hopper, architects Frank Lloyd Wright and William Van Alen, Joseph Stella, Dorothea Lange, and Louis Tiffany. The latter half of the last century includes works by Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Richard Diebenkorn, and Martin Puryear.

“We wanted lasting images that were meant to be lived with, that the students can grow with,” says Bays. “A student can look at it in first grade and see one thing, and then look at it again in high school and see it differently.”

Another set of images might be used to illuminate the Civil War period. It includes a relief sculpture, a photograph, and a painting. The sculpture is the bronze Robert Gould Shaw and the Fifty-Fourth Regiment Memorial, completed in 1897 by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and situated at the edge of Boston Common. The work commemorates Colonel Robert Shaw, the privileged son of a Boston abolitionist who gave his life for the Union cause. It also honors the unit he commanded, the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the first regiment of African Americans recruited in the North to serve in the Union Army, and the subject of the Hollywood film Glory.

The photograph was taken by Alexander Gardner. The subject is President Abraham Lincoln, who sat for the photo in February 1865, near the end of the Civil War and not long before his assassination. Lincoln's face reveals the effects of the war—his craggy, tired face is plainly presented, not softened even though it is partly in shadow. He wears a simple black suit and white shirt. His tie is a askew. And in his hands he holds his eyeglasses, giving the impression he's impatient to leave.

Winslow Homer's The Veteran in a New Field was painted in 1865, soon after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox. It portrays a Union soldier, having returned home from the war, toiling in a wheat field. The painting calls to mind the veteran's previous work in another field—a battlefield. Homer conveys both the optimism of rebuilding the nation and the desolation and destruction of war.

“These three works can be considered in many different ways,” says Bays. “For example, one could look at them as revolving around Lincoln: the portrait revealing the man in his own time; the relief referring to the soldiers he commanded; and the painting portraying the effects of the war. They could also be studied as how an individual faces challenge—whether a president, a soldier, or a veteran,” says Bays.

The opportunity to integrate many school subjects with the study of art drew Elizabeth Panhorst to Picturing America. Panhorst, a program assistant at the Caroline Marshall Draughon Center for the Arts and Humanities at Auburn University, has helped ten rural schools in Alabama receive grants to be part of the pilot project. “The reproductions can be used in so many ways,” says Panhorst. “I see [Picturing America] as particularly rich for writing and literature studies” She notes a special link between two of the works and Alabama history: James Karales's photograph “Selma-to-Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965” and Martin Puryear's 1996 sculpture Ladder for Booker T. Washington.

“The artworks represent significant achievements in American art, and can reveal much about the culture and societies that produced that art—important insights for students of any age,” says Panhorst. “I can imagine instances where a whole class will get charged up and, at the same time, get a better understanding of history.”

This is the kind of enthusiasm Cole envisioned when he developed the idea for the program. “As someone who has taught the history of art, it surprised me how little undergraduates knew about history or art in general,” he says.

“I was one who grew up in a house with no art. When I was young, my parents took a trip to Washington, D.C., and brought me back a portfolio of 8 x 10 illustrations from the National Gallery of Art.” Cole especially remembers a print by the fifteenth-century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch. “I found it compelling—I had an epiphany.”

“Flipping through those images, as I absorbed and pondered these great works, I had the first glimmerings of what would become a lifelong scholarly pursuit: to study and understand the form, history, and meaning of art.”

He hopes the same will happen for the students participating in Picturing America. “I see works of art as primary documents of a civilization,” said Cole in 2002, when the program was conceived.

“The written document tells you one thing, but a painting or a sculpture or a building tells you something else. They are both primary documents, but they tell you things in different ways. I feel strongly that this program will be a lasting contribution of NEH.”