Audubon was unique among all the other immigrants and frontiersmen because he put his business interests aside and decided to live for his art," says Larry Hott, director and coproducer of American Masters' John James Audubon: Drawn from Nature. "Although that kind of philosophy appeared a lot in 1960s hippie culture, it wasn't a big part of the American frontier experience."

Drawn from Nature, a new NEH-funded documentary, is the story of a man full of such contradictions. Audubon was both a cunning entrepreneur and a rugged outdoorsman, as comfortable in the drawing rooms of Europe as the unmapped forests of America.

Today, Audubon's name is synonymous with American conservation, but he was an extravagant hunter. "Audubon didn't think it was a good day unless he'd killed a hundred birds," Hott says. "In his lifetime, he killed thousands. Yet Audubon began writing about loss of habitat earlier than anyone else in America. He was the first to sound the clarion call that there was a problem."

Audubon's work itself is endangered. Octavo editions of Birds of America, a seven-volume set of 650 hand-colored prints published in 1840, are being torn apart so that prints can be sold individually. "I hope to convince people that these sets are more valuable intact than they are apart," says Roswell Eldridge, who organized the Audubon conference at which Drawn from Nature premiered last fall. "Audubon produced the most extraordinary art book in the United States."

It took Audubon more than a decade to complete his ornithological catalog, often at the expense of his family and finances. He spent hours observing birds in their natural habitats, then shot them, using scatter pellets to lessen the damage to their bodies. For Audubon, Eldridge says, "a bird was like a rose. You admired the color, you admired the fragrance, and you picked it without much emotional reaction."

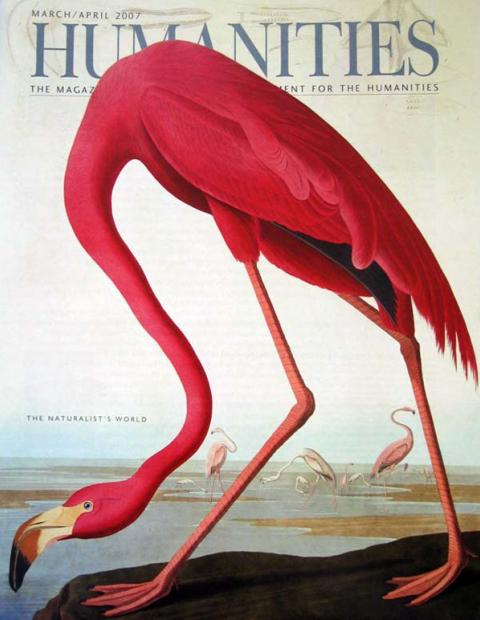

Audubon pinned his specimens to a wooden grid, arranging their wings, tails, and heads in lifelike positions. Using a duplicate grid, he sketched the birds exactly to scale, reproducing each feather to the smallest detail.

It's not only anatomical precision that makes Audubon's paintings so captivating, Hott says. "His work is emotional. His birds are anthropomorphized; they have personalities. You begin to care about these birds. This is what separates Audubon from other ornithological artists."

Birds of America is not only an arresting visual feat, but a literary triumph, Hott explains. Audubon, for whom English was a second language, describes the behaviors of each bird with remarkable wit and affection.

Audubon was born in Haiti on April 26, 1785, the son of a French ship's captain and a local chambermaid. His mother died six months after his birth, and Audubon was reared by a group of Haitian women until a slave rebellion forced Captain Audubon to flee with his son to Nantes, France, in 1791. But the French Revolution and counterrevolutionary efforts allowed no respite from the violence in Haiti. Audubon witnessed the imprisonment and slaughter of hundreds of townspeople. So many prisoners were drowned in the nearby Loire River that it became unsafe to fish there for years.

The horrors Audubon experienced as a child shaped the course of his adult life, says Richard Rhodes, author of John James Audubon, a 2004 biography. During his adolescence, Audubon spent more and more time in the forest studying wildlife. He was particularly interested in bringing animals back to life, Rhodes says. "He couldn't really reanimate them, but he discovered he could draw them. There's a linkage between his almost-obsessive fascination with nature and the trauma of his childhood experience. It's much easier to look at birds in their environment than to connect with people."

In Audubon's art, however, the natural world is not always peaceful. Many paintings show birds in pursuit of prey; Audubon depicts peregrine falcons engaged in a frenzied, bloody attack on a pair of ducks. "It's an arresting image," says Audubon scholar Bill Steiner. "Audubon knew that animals kill other animals for the pure joy of it. When these prints go up for auction, you can feel the room tense up."

When Audubon was eighteen, he left France to avoid conscription in Napoleon's army. He assumed control of an estate his father had purchased outside of Philadelphia. According to Rhodes, Audubon was a member of the first "truly American" generation. "Audubon couldn't have been more French when he arrived," Rhodes says. "But he moved west, he became an explorer, he founded businesses, he turned himself into a professional artist—what could be more American than having two or three careers?"

In Philadelphia, Audubon filled his library with natural artifacts—animal skulls, skins, and his own collection of drawings. Within a year he met Lucy Bakewell, the reserved, educated daughter of his neighbor. She became his wife, and one of the dominant influences in his life. "Lucy and Audubon were a curiously modern couple," Rhodes says. "He gave her full credit for her intelligence, wisdom, and understanding. He displayed very little of the paternalism prevalent in nineteenth-century culture."

The Audubons moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and established a general store. Their first son, Victor, was born in 1809, followed by John Woodhouse in 1812. Audubon opened a second store and quickly became one of the wealthiest men in the community. He built a steam mill, an enormous investment which proved difficult to manage. Soon, Audubon's dedication to studying and drawing birds began to interfere with his business.

The Panic of 1819, a sudden economic depression which caused banks across the United States to call in their loans, cemented Audubon's financial trouble. He was jailed and forced to declare bankruptcy. The Audubons' house and possessions were put up for auction. Because no one wanted Audubon's paintings of birds, they were returned to him. The bankruptcy shattered Audubon emotionally. According to Rhodes, Lucy Audubon realized that her husband's dream of creating an American ornithology was essential to rebuilding his self-confidence. "She knew the book would give him back feelings of worth as a human being, as a man," Rhodes says. In 1820, Audubon left Lucy and his children and set off down the Ohio River in search of specimens for what would become Birds of America. A year later, he arrived in New Orleans, where he earned a living by painting portraits. One day, a veiled woman approached him and asked him to draw her in the nude. Audubon, though shocked and nervous, complied. Strangely, he recounted the colorful incident to Lucy in a detailed letter.

"We wondered whether we should include this scene in the film. Is it gratuitous?" Hott says. "In the end, I'm glad we decided to keep it. This is the kind of thing that drew us to Audubon. He was a real man with real passions and weaknesses. He suffered for his art, and his wife and family suffered too."

Audubon took his portfolio to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, hoping to find a publisher for Birds of America. Unfortunately, his arrogance and unkempt appearance alienated his potential investors. Convinced that his book would never be printed in the United States, he sailed to Liverpool. In England, Audubon's rugged provinciality made him an overnight sensation, Rhodes says. James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans had been published six months before his arrival. The novel's widespread popularity generated dozens of spin-off products, such as character dolls and painted dinner plates.

Audubon's outdoor dress, shoulder-length hair and bronzed skin seemed like a vision straight out of the novel, although "he was actually a fairly sophisticated urban man," Rhodes explains. Audubon was immediately invited to dinner parties in all of the city's finest homes.

"He was charming—he played the violin, he danced, he knew all the frontier lore. The English ladies would say, 'Oh, Mr. Audubon, give us an owl call. Oh, Mr. Audubon, show us how the Indians dance," Rhodes says. "He wearied quickly of being the cardboard frontiersman, but he knew these people were his potential subscribers."

Audubon toured Edinburgh, London, and Paris with his portfolio under one arm and single-handedly raised the money necessary to finance his project.

It was not simply Audubon's exotic appearance that impressed Europe's elite, but the originality of his art.

"People were starved for images in those days," Rhodes explains. "Audubon's work is full of energy, life, love, violence, and color. To walk into a hall filled with his paintings would have been like seeing an IMAX movie today."

Turning Audubon's watercolors into prints was itself an elaborate process. Robert Havell Sr., London's preeminent engraver, took on the bulk of the project. Havell and his assistants traced every detail of Audubon's original paintings and transferred the images to copper plates. "It looks like the image has been printed on the copper—it's so shallow, so fine," says Steiner. Completed prints were circulated among fifty or sixty watercolorists, primarily young women, who were responsible for filling in a single color each. A master colorist made final changes, Steiner explains, and therefore "every print is different."

One of Audubon's most striking works is the golden eagle, a painting which includes a rare self-portrait. Beyond the eagle, which clutches a rabbit in its talons, a hunter shimmies across a log with a sling of birds on his back. Robert Peck, a fellow of Philadelphia's Academy of Natural Sciences, suggests that Audubon's self-portrait, although it never appeared in the final print, represents his understanding of the relationship between humans and nature. "Nature is up front and the human race is a diminutive footnote," Peck says. "It's the reverse of the usual representation."

Many of the birds Audubon painted are now extinct, along with much of the American wilderness that was their home. The Carolina parakeet, the passenger pigeon, and the Eskimo curlew were gone within decades of Audubon's death. "There was such an abundance of wildlife in his youth that he and everyone else thought the supply was infinite," Peck explains. "But as he grew older, he was disappointed by the terrible destruction he saw."

Today, Audubon's legacy lives on through the National Audubon Society, an organization dedicated to preserving America's natural heritage.

"Most people know the name Audubon," Hott says, "but they don't know much about him." Drawn from Nature is the tale of a man who destroyed the birds he loved, of a hunter who took a lifetime to become a conservationist. Audubon was a blend of American simplicity and European sophistication, of artist and entrepreneur. He was passionate, extravagant, and faultlessly loyal to the birds which made him famous. "It's a love story," Hott says. "That's what's so great about Audubon."