By the mid 1960s, the tides had begun to change in how scholars told the history of slavery. For generations, historians propagated the narrative that slavery benefited people of African descent because they were innately indolent, inferior, and in need of white supervision. Beginning in the 1940s, scholars began to challenge that view by uncovering accounts of slave revolts as well as compelling evidence of everyday acts of resistance and defiance. This scholarship found its audience not among academics but in the general public. These new interpretations also helped galvanize the civil rights movement, uncovering a tradition of black resistance that inspired a range of other social movements.

Labor union activists in New York City attended the Jefferson School of Social Science, which was founded by the Communist party to educate the working class about the principles of Marxism. There, historians who had been blacklisted from the academy taught working-class adults about the history of slavery. They used evidence of slave rebellions to illustrate the power of an oppressed population to revolt against those in power. One of the students in the class, Bernard Katz, rushed home to tell his two sons, Jonathan and William, over dinner about the heroic stories of black resistance.

For the Katz family, stories about slavery offered an historical explanation for the racial injustices that were exploding on the streets outside of their home. The history of black resistance then led the Katz family to research and publish books that highlighted this history. In response to the uprising in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles in the summer of 1965, William Katz published Eyewitness: A Living Documentary of the African American Contribution to American History, which was an anthology of testimonies by iconic African Americans from Harriet Tubman to Martin Luther King Jr., offering an historical corrective to myths about black dependence and inferiority.

William’s brother Jonathan also became enamored with black history and wrote two works based on archival evidence, Black Woman: A Fictionalized Biography of Lucy Terry Prince (Pantheon, 1973) and Resistance at Christiana: The Fugitive Slave Rebellion, Christiana, Pennsylvania, 1851 (Crowell, 1974), which signaled to him, as he later recalled, “the importance of resistance.”

By 1976, Jonathan Ned Katz, who had been trained as a textile designer, had come out of the closet and become involved in the gay liberation movement, which officially commenced in 1969. LGBT people had resisted arrest at a mafia-owned gay bar, The Stonewall Inn, during a police raid. Their revolt was the tipping point of formal LGBT political activism that can be traced to the early 1950s. Katz immediately drew analogies between black resistance and the rise of gay liberation. He then came across a pamphlet, written by two gay activists, about the Nazi persecution of gay people during WWII, which, at the time, had not been recorded in any major history book and was not even part of the public memory.

Learning about this history, combined with his research in black history, led Katz to the New York Public Library, where he began a massive effort to find historical evidence about LGBT people from the past. He eventually uncovered a range of primary source documents from colonial court cases on sodomy to anecdotes about Willa Cather to political slogans from the lesbian activist group Radicalesbians to then contemporary news reports of gay men being arrested for “disorderly conduct.”

Katz initially decided to present his findings as a play in order to reach the largest audience. On June 16, 1972, Katz’s play, Coming Out!, premiered at a firehouse in the West Village, which a gay political organization had rented. Coming Out! received rave reviews and, the following year, it reopened to coincide with the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising at a theater in Chelsea, a New York City neighborhood.

That July, noted historian Martin Duberman reviewed it for The New York Times and encouraged a publisher to offer Katz a contract to turn the play into a book. Katz initially was reticent and even a bit intimidated. He was also not sure there was enough material to constitute an entire book.

Despite these doubts, Katz worried more about the implications if he did not publish. He had witnessed how, with the exception of a single pamphlet, there were few documents about the persecution and murder of thousands of gay men and women during Hitler’s reign. He also recognized how the Nazis destroyed evidence of a thriving gay community in Berlin before Hitler took control of Germany. Consequently, he feared that the history of gay liberation in the 1970s also risked not being documented. He had little confidence in professional historians. In a conversation with me in 2012, he described how the American Historical Association (AHA) did not represent or even care about the history of gay people in the 1970s. Social history was just gaining traction within the profession with books portraying African Americans, women, the working class, and other marginalized groups as principal historical actors. But even with this radical shift, Katz had little confidence that the AHA would commit itself to respecting, teaching, and centering gay history. Katz did not have a doctorate in history, let alone an undergraduate degree, so he sadly had little standing or affiliation within the profession—though he remains one of the most prolific and important gay historians four decades later.

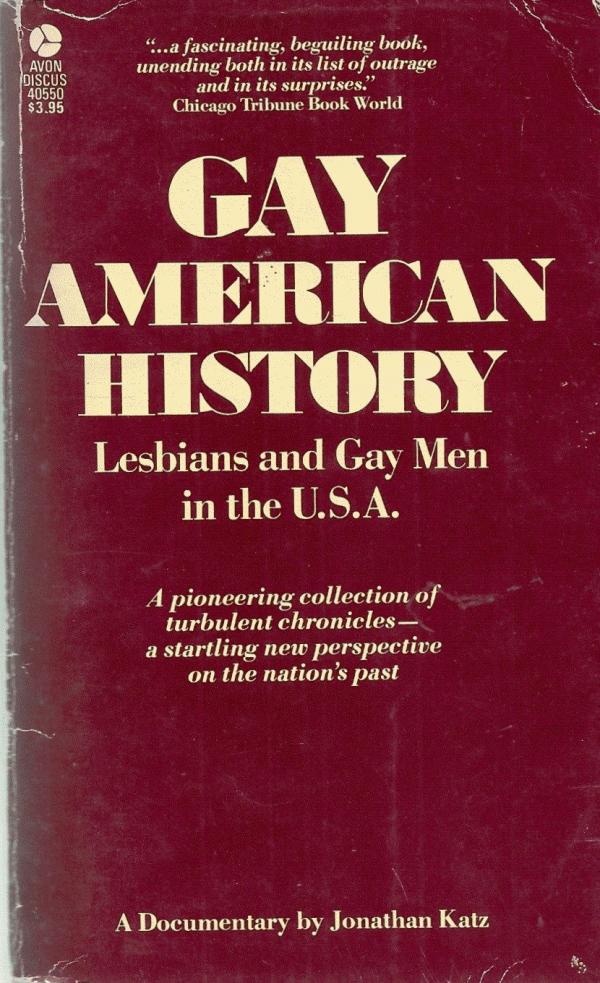

Katz, nonetheless, pursued turning his play into a book. He returned to the archives and found even more evidence, which he then published, in 1976, as the first LGBT anthology of primary sources, under the title Gay American History. While many professional historians did not appreciate his book, the gay community embraced it. He became a rock star within the gay community, giving talks throughout the nation, appearing in LGBT newspapers, and finding readers around the world. In the 1970s, the emergence of gay history, like black history, began on the streets and then eventually made its way into the academy.

While Katz’s book remains a leading contribution to the field and scholars continue to study the history of gay liberation, for many LGBT people of color and transgender people the story of liberation proves to be incorrect. In February 2019, the Stonewall National Museum and Archives hosted a gala and awarded Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, who had witnessed the Stonewall uprising in 1969 as an activist, with an icon award. A prominent transgender woman, Griffin-Gracey was not pleased with the recognition. In an interview with Vice Magazine, she explained how there were no white gay men at Stonewall. She remembers the street queens of color on the frontlines, pushing the police back and leading the revolt. Over time, however, the heroic efforts of trans people of color have been overlooked and white men have appeared as the leading protagonists in the Stonewall uprising. When presented with the icon award, Griffin-Gracey reminded the mostly white, gay, affluent audience that trans people actually led the charge for equality.

Her claim is not without merit. One of the first recorded political uprisings occurred in August 1966 in San Francisco, before Stonewall, when a group of transgender people who were banned from a local bar gathered at Compton’s Cafeteria. The police accused them of loitering and began to arrest them. The transgender people fought back, marking one of the earliest recorded LGBT political acts of resistance against the police.

Despite the fact that so many gay people, like Jonathan Ned Katz, gained insights and strategies about protest from the civil rights movement, once gay liberation gained momentum, many people ignored, forgot, or overlooked the contributions of trans people and people of color. Before Stonewall, gay activists had used the Liberty Bell as a symbol of their movement since it had been used by nineteenth-century abolitionists who opposed slavery and was later adopted by suffragettes. But, after Stonewall, the links to these early movements faded.

In 1970, Carl Wittman, a gay activist, wondered if civil rights led to the rise of gay liberation in his infamous pamphlet A Gay Manifesto. “How it began we don’t know,” Wittman wrote, “maybe we were inspired by black people and their freedom movement.”

Since it is difficult to identify a single factor or cause to explain the emergence of a social movement, Wittman’s question about the origin of gay liberation makes sense. His statement, nonetheless, illustrates the ways in which the influence of black civil rights had begun to disappear from the narratives about the origin of gay liberation.

During the 1970s, the mostly white gay press continued this erasure of people of color by presenting their coverage of minorities as groundbreaking. The Ladder, which was a lesbian magazine, published a story, “Women’s Liberation Is Our Thing Too,” by an African-American woman activist, Anita R. Cornwell, in October 1971. She offered a candid account of the racism and sexism that women of color faced in the black freedom struggle in the United States and across the globe, offering examples from the then recent Algerian War of Independence. Cornwell also alerted the mostly white readership that the white women who complain about sexism from white men are the same women who black people refer to as “Miss Anne,” a slang term that emerged during slavery as code to describe white women. She claimed that white women are now interested in “gay liberation,” “lesbian liberation,” “free child care,” and “abortions,” without acknowledging their oppression of black women.

While Cornwell exposed the racism within both the white feminist and LGBT liberation movement, the publication of the article actually reified the misunderstanding that gay liberation originated with white people. Treating Cornwell as an outsider to a movement that people of color played a major role in forming unwittingly conspired in whitewashing the origin of gay liberation.

Other queer papers from the period also highlighted people of color and “third world people,” which was popular parlance for subjugated people across the globe, as revelatory. Boston’s Fag Rag collaborated with San Francisco’s Gay Sunshine for a special joint issue on the fifth anniversary of Stonewall in 1974 and featured an article titled “Personal Reflections on Gay Liberation from The Third World.” The contributor explained, “There is much in the organized gay liberation that non-white people are unable to identify with. We find ourselves feeling the alienation that James Baldwin describes in Autobiographical Notes, when he goes to the great achievements of Western Art and Culture, and sees nothing of his history, of his accomplishment. What so many of the whites in Gay Liberation fail to comprehend, or perhaps admit, is that Gay Liberation is basically a white phenomenon of the late 60s.” Despite the actual contributions of people of color to the beginning of the movement, the cultural memory of Stonewall, as early as 1974, as this article suggests, was already showing signs of it being misunderstood and misrepresented.

Throughout the 1970s to the present, racism, classism, transphobia, xenophobia, and other forms of oppression have divided the gay community. Even in the reporting of the Pulse massacre in 2016, which was the largest massacre of LGBT people in history—the victims were people of color—few reporters and pundits paused to consider why the club hosted a Latin night in particular. Beyond an appreciation for Latino culture, many gay bars, clubs, and neighborhoods had been by both law and custom segregated, so special nights have been created to recognize diversity within the LGBT community.

The fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall offers a chance for many people to learn the history of gay liberation and for those who are more familiar with the general contours of the story to reckon with the fractures that have divided it.