It was 2002 and Maya Angelou wanted to do something “daring.” She was the author of more than ten books of poetry and five autobiographies, including I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), which stayed on the New York Times best-seller list for two years and helped usher in an African-American women writers’ renaissance. She had recited her verse before large audiences on countless occasions, including the inauguration of President Bill Clinton. She was famous and successful, but still she had to defend her creative decisions.

Billy Collins, then U.S. Poet Laureate and a fellow Random House writer, questioned Angelou’s partnership with Hallmark, the largest manufacturer of greeting cards in the United States and, among the literati, commonly associated with trite expressions.

“It lowers the understanding of what poetry actually can do,” Collins said to the Associated Press. “Hallmark cards has always been a common phrase to describe verse that is really less than poetry because it is sentimental and unoriginal.”

Angelou’s words stirred emotions, though her life was no simple greeting card. She had entered the literary scene with an unflinching narrative about her rape as a child, self-imposed silence, sustained emotional resilience, and, finally, triumphant overcoming. Uplift was, actually, part of her writing style, and she viewed the collaboration with Hallmark as an opportunity to take her message of compassion, understanding, and transformation to a larger audience.

“My problem is I love life, I love living life and I love the art of living,” she said in a 1977 interview. “I try to live my life as a poetic adventure, everything I do from the way I keep my house, cook, make my husband happy, or welcome my friends, raise my son; everything is a part of a large canvas I am creating, I am living beneath.”

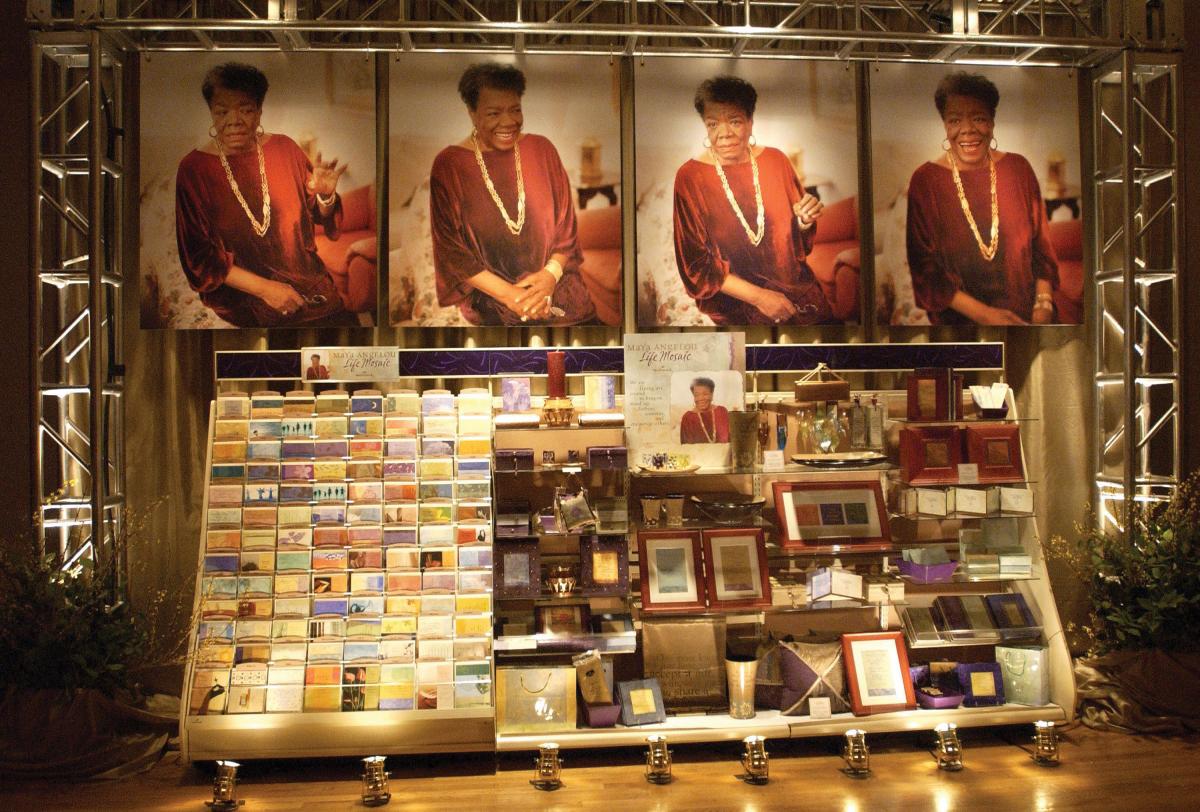

The product line with Hallmark became the Life Mosaic collection. It included everything from inscribed bookends, bookmarks, and bookplates to recipe albums, picture frames, and treasure boxes. They were like keepsakes from Angelou’s poetic life, literary art you could use, gift, and display.

Angelou’s collaboration with Hallmark was bold and profitable. It was distinguishable from Mahogany, Hallmark’s first imprint, broadened in 1991, to target African Americans year-round. Life Mosaic traded on Angelou’s personal brand of poetic sentiment, indebtedness to African-American oral traditions, craft as a memoirist, and woman-centeredness. It valued her personal bond with the public.

“At the beginning of her literary career, readers viewed Angelou as friend, sister, and mentor,” explained African-American literature scholar Cheryl A. Wall when Angelou died in 2014. “By the end, she assumed the status of elder, teacher, and guide.” Angelou’s knowing sensibility, conveyed throughout her literary work, appealed to popular audiences, and Life Mosaic generated $45 million in its first five years for Hallmark and more than $4 million for the woman who inspirited it.

The universal values and insight in Angelou’s poetry and prose made Hallmark an ideal match for her. Early interviews illustrate that Angelou talked with a Hallmark-like affect, a way of speaking that delivered life lessons with aplomb. An adage she offered in a 1987 interview, “Life is a gift, and I try to respond with grace and courtesy,” reappears in the production notes for a Life Mosaic card planner, archived along with Angelou’s papers at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Hallmark staff mined her interviews, publications, and their own conversations with her for material. They then condensed and expanded her words, and she edited and gave final approval. Copy for a planned birthday card’s cover reads, “Love life. / Love living life. / Enjoy the art of living. / Maya Angelou.” The text for the card’s inside content is amended in Angelou’s handwriting: “Your life is a masterpiece / waiting to be created / Do[Live] it with passion!”

The feedback Hallmark staff solicited from customers and retailers proved that Life Mosaic was more meaningful than commercialized cliches. Buyers’ comments testified to joblessness, divorce, sexual assault, and suicidal thoughts in an effort to make evident to Hallmark, who reported to Angelou, the positive impact of her products. Their wording helped card senders express themselves while empowering recipients to deal with their emotions. A daughter relayed that her mother, who had cancer, felt Angelou “knew her and exactly what she was feeling,” reminding her that she “gets her strength from within.” Angelou’s Life Mosaic lifted people up and assisted them in the difficult art of living.

It also extended an invitation for people to embark on their own poetic pilgrimages. “Friendship,” “imagination,” “laughter,” “discovery,” “faith,” and “spirit” are impressionistically displayed on a mock-up cover of the Life Mosaic interactive journal with the quote “Life is pure adventure.” The inside cover of the hundred-page, nine-inch book, designed to be bound in purple and sheer gold fabric, briefly describes Angelou’s biography as a “kaleidoscope of courage, / creativity, and inspiration.” The journal encourages its owner “to explore the remarkable wonder of YOU,” and the ensuing pages call her to commune with Angelou through meditative composition.

One page intones: “Courage allows the successful woman to fail—and to learn powerful lessons from the failure—so that in the end, she didn’t fail at all.” Another succinctly avows: “We have a SISTERNESS about us.” Sometimes Angelou’s affirmations are placed beside blank lines for journaling; sometimes they are above; sometimes they are arranged in between the dedicated writing spaces. In this way, the journal fosters interplay between the owner’s personal history and Angelou’s truisms. “What a wonder!” she prompts in the front matter. “To think about your life / . . . To have a place / to write down / what you’ve been thinking— / a place you can return to / to rediscover yourself.” These opening words, a bid to join Angelou’s self-reflective writing practice, end with “Joy!” and her signature.

In a 1981 interview, Angelou told Wall: “A good autobiographer seems to write about herself and is in fact writing about the temper of the times. A good one is writing history from one person’s viewpoint.” Angelou not only chronicled her history, but she was also a history maker in ways that are not often remembered.

She was the first Black woman to make the nonfiction best-seller list and the first to have a production company film her screenplay. She was the first Black person and the first woman to recite a poem at a presidential inauguration. Making publishing history, “On the Pulse of the Morning” was also a best-seller, and it was awarded a Grammy. Angelou raised funds for Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights organization; her role as Kunta Kinte’s grandmother in the miniseries Roots was nominated for an Emmy; she and her poem “Phenomenal Woman” were featured in John Singleton’s film Poetic Justice. She became an icon by the 1990s, aided by the selection of her fourth autobiography, The Heart of a Woman, for Oprah’s Book Club and a televised discussion with pajama-clad Winfrey and a select group of readers in her living room.

Literary circles primarily celebrate Angelou’s innovation to American autobiography. In telling her story, she set out to write autobiography, as well as history, as literature. “Her autobiographies did more than lift the veil on subjects that had been hidden,” Wall clarifies. “They insisted that the protagonist’s feelings were as important to the narrative as the events it describes.”

Angelou had an intense, five-days-a-week writing process, which included five hours of writing in the morning and several hours of editing in the evening. She devised a cognitive method to distance her present self from her past self to allow readers to immerse themselves in her former life. She called the mental exercise a “kind of enchantment.” She also attempted to put herself “in a mood,” one contrary to the tone of her work, “to fight against it” in her writing. When Angelou began the Life Mosaic collection, she was finishing her sixth and final chronological book in her autobiographical series, A Song Flung Up to Heaven (2002). The memoir coheres around grief: The murders of Malcom X and Martin Luther King Jr. bookend her narrative about the mid 1960s. In comparison, Life Mosaic imparts gratitude for birthdays, graduations, and holidays; it was the salve to her writing mood.

Angelou realized that lending her name to Hallmark could possibly damage her reputation, but she liked to be challenged. At the end of A Song Flung Up to Heaven, she revealed that she wrote I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings because her future longtime Random House editor said writing autobiography as literature was “almost impossible.” The two-sentence epigram, the hallmark of the greeting card, was a new genre for her to master. Angelou was used to being criticized for the speed and frequency with which she published books. In response to her new detractors, she unapologetically stated that she undertook the Hallmark enterprise because she wanted her work read and put in the hands of people who did not buy books. Life Mosaic was a quotable—and sometimes portable—Angelou reader.

Ultimately, Life Mosaic reinvented Angelou’s autobiographical self in an immediate, recurring fashion. It was not her most esteemed work, but it was no “less than poetry” (to use Billy Collins’s phrase) nor any less inspiring. It was an abridged form rooted in the whole. Besides, Angelou knew all writing was not one and the same. “Now, not everything you do is going to be a masterpiece,” she counseled in a 1976 interview. “Sometimes you really do, you write that masterpiece. . . . The other times you’re just stretching your soul, you’re stretching your instrument, your mind. That’s good.” Life Mosaic did not end her career, as she followed it with another autobiography, several volumes of poetry, a collection of essays, two cookbooks, and a series of children’s books. Rather, it added to the range and innovation of Angelou’s body of work, and it stretched her readers’ souls and minds, too.