To wide acclaim, the Library of America recently published African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song, a new volume of classic American poetry supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Kevin Young is the savvy editor who pulled it together.

Young has been called “America’s busiest poet.” He publishes a new book every few years or so. He is poetry editor of the New Yorker, to which he also contributes essays. Until recently, he was director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library. In January, he assumed the directorship of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

HUMANITIES: Where are you from, and how did poetry enter your life?

KEVIN YOUNG: Well, I moved around a lot as a kid. So “from” is always a harder question than it might seem. I grew up in part in Kansas. That’s where I went to high school, and I moved there when I was nine, but I moved six times before that.

For me, home was always more Louisiana, where both my parents are from. And Louisiana is what I first started really writing about in depth. My first book was about the South and the way of life there.

My parents grew up in the rural segregated South, and I was much more focused on the fact that they grew up in Black environments. I really wanted to understand what I think I’ve been interested in for the rest of my writing career, which is “the Blackness of Blackness,” as I said in the subtitle to my nonfiction book The Grey Album. I was really interested in what makes Black culture unique and its own—its traditions, foodways, the humor and the pleasure and, you know, some of the blues notes, too. I wanted to capture this fullness of tradition, and that’s what drew me to writing.

HUMANITIES: When did you become interested in history?

YOUNG: I suppose I was always fascinated by history. I didn’t study it formally or anything like that, but I was always interested in the ways things came about. And I think, for me, poetry always got at that. The historical poem is as old as poetry itself. People sat around and talked and spoke and told the tale of their people. And I think that’s one of the poet’s roles.

I think my passion for history came about from curiosity and wanting, at times, to know more than I was told and also to dig further into archives and places that preserve this history—including some where I have had the fortune to work—and where they preserve it in full, but we often don’t have the interpretation of the fullness. I really wanted to capture that.

HUMANITIES: While editing this volume, you were director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library. What is the purpose or mission of the Schomburg?

YOUNG: The Schomburg Center collects, preserves, and provides access to Black culture worldwide, and it’s done so for nearly a century, now ninety-six years old this January. That longevity is really important as the Center has long provided the context of Black history, and so when events like last summer happen, the Schomburg Center was there to help people understand that this was both new and yet precedented, very much so. There were antecedents to what we were experiencing.

The Schomburg Center has the papers and archives of so many fascinating people. When I was there, James Baldwin’s papers, Sonny Rollins’s archive, and the archives of Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis all came home to Harlem. There is a real range of figures, historical figures, political figures, business people, and newer additions, including the archive of the late Gertrude Hadley Jeannette, the first woman of any color to have a hack license in New York City. There’s an amazing picture of her with her taxi driver’s hat jauntily on. She was also an actor and a playwright. She performed on the American Negro Theatre stage, which is in the bottom floor of the original Schomburg Center building.

There’s all these connections, and that’s the kind of history I think the Schomburg Center illuminates for us. It is public history, but also history from the private lives of public people, a history we continue and explore intimately at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which I direct now.

HUMANITIES: There has been an enthusiastic response to African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song. It is certainly finding an audience, but while you were working on it who did you imagine that audience would be?

YOUNG: That’s a great question. I was working on the book for six years, and there were moments there where I was like, ‘Who’s going to read this?’ You know, like the sixth poem by this poet that even I had never heard of until ten minutes ago? But I actually think that’s what’s great about it. There is a breadth of Black poetry, a rich tradition, that is 250 years old. And a quarter millennium is a long time. But the collection doesn’t only contain greatest hits. It’s got some deep tracks, too.

The hardest thing was to cut back on Langston Hughes or Gwendolyn Brooks from, you know, 50 pages or so to 22 or 23, which is still quite long. Doing so allowed us to talk about some of the other writers around them and provide that context.

For me, the anthology is great as an introduction to Black poetry, that rich American tradition. And there are still discoveries to be made. I think it’s good for your bedside table and for the classroom as well. It has so much to offer, and I especially can see that now that it’s in hardcovers.

HUMANITIES: In the introduction, you describe it as a powerful volume of American history. How so exactly? How do you think that historical aspect takes shape in the reader’s mind as they make their way through?

YOUNG: Well, the anthology is organized into eras. In that way alone, it gives you a sense of not so much the march of history, but the conversation of history.

The first section has Phillis Wheatley and other poets writing in enslavement or about enslavement. This first part is chronological, which shows you that struggle and song across time. And then for the past century and a half or so, the sections are split up alphabetically by eras, revealing the ways people are talking to each other within times and across time.

That quality, I liken it to a conversation. Someone’s commenting on the death of Emmett Till—as Gwendolyn Brooks so powerfully does shortly after his murder in 1955. And then you have poets like Eve L. Ewing writing about Brooks writing about Emmett Till in the present day.

That’s a 65-year span, longer even, when people are talking about Emmett Till, you know? And things like last summer and the injustices we saw and George Floyd’s murder deeply connect to this kind of ongoing concern poets have.

To me, it’s a conversation between poets; a conversation with history; and a conversation with current events, a conversation with now.

HUMANITIES: As a reader, I expected to find many poems about slavery and injustice and race, but I also found poems about math, menopause, and war. How did you think about diversity of tone and subject within the larger collection?

YOUNG: The poets themselves take care of that. They write about boredom and joy, and about having a job and losing a job. One of the great poems is about working in an English department. It’s a tradition of people writing about their questions. They’re writing about their lives. But they are also writing against the notion that there shouldn’t be politics in poetry.

African American poets have been writing about everything from music to politics, in ways that have proven prescient and that have proven especially relevant now. As the poetry editor of the New Yorker, I’ve seen up close the ways that people try to contend with our times and write about what happened just yesterday. And I think Black poets have been particularly able to do that and have developed a tradition around it to make history musical, to make the struggle sing, and then also to sing about whatever they want.

It’s a little like Irish poetry in that sense. We can’t imagine an Irish poetry that has nothing to do with the world around it. I studied with Seamus Heaney and that whole tradition would be much less rich if it didn’t think about the times we’re in.

The key is to find a metaphor, a way to talk about these things. And I believe the poems in this book show that if you do that really well—as Gwendolyn Brooks does, as Langston Hughes does—topical poems can last a long time.

HUMANITIES: Tell me about the relationship between African American music and poetry. Also, does one need to understand the first to understand the second?

YOUNG: I’ll tell you a story. I had someone ask me for help finding a poetry critic, someone who writes about Black poetry. And I suggested a critic who writes about poetry and music and all this Black culture. And they were like, ‘I only want a poetry critic.’ And I was like, ‘That’s a terrible critic, you know, of Black poetry who would never think about music.’

That’s one of the reasons I wanted that subtitle “Struggle and Song.” It wasn’t just to mean music in the world. It was to mean music in poetry.

Since its start, Black poetry is very concerned with oral literature, and by that I mean both music and the spoken qualities of poetry. Black poets from Dunbar on—even going back to Lucy Terry in the colonial era—have always written about and wrestled with the questions of how do you capture speech on the page and how do you capture song.

To me, this is the point of the lyric. Lyric poetry descends from that idea of music to accompany the lyre. And so to turn the lyre into a banjo or a bass doesn’t seem that far off to me.

Black poets were always drawn to music, and music provided a way to talk about folk heroes, to champion someone like John Coltrane, say, in the 1960s as someone who was incredibly sophisticated, making a complex music. How do you reflect that on the page, you know? And that music on the page, in the ’60s, June Jordan called it “vertical rhythm,” a description I love.

How do you capture Coltrane’s famed sheets of sound? Also how do you capture the way that my grandmother talks? That’s what has consumed me.

I think it goes to one of your earlier questions, which is, Who’s the audience? And, for me, I’ve never seen my grandmother in a poem. Whoever it’s for, it might be for my grandmother. It might be for me. It might be for someone who was looking for some version of themselves. And, you know, I think you can learn a lot just overhearing a tradition.

From Langston Hughes’s capturing of the blues poem, I think you see that music is a renewable resource for poetry. I try to get people to understand it’s not that Langston Hughes put blues in poetry to raise up the blues. It was the opposite. He was trying to get at the power that the blues provided when he was sitting in that audience hearing Bessie Smith sing. He wanted to capture that in poems, this voice singing straight to us, an I that was also a we. That was inclusive, and I think he did capture that.

HUMANITIES: The book has been praised for highlighting the contributions of female poets, especially during the Harlem Renaissance, but elsewhere, too. Is there a revised history of women poets hiding in plain sight in this collection?

YOUNG: Absolutely. I wanted gender balance and a real array of LGBTQ voices, to show the diversity within Black poetry. And women, especially, because in the Harlem Renaissance, not many women were publishing books. So they can be over-looked if you just look on the bookshelf. But, luckily, a lot of scholars, who I credit in the introduction, have gone and done a lot of that work of finding their poems. And some of those poems are some of my favorites in the anthology.

There were bare spots, though, where it was far harder to find poets, and I don’t just mean women poets. Like in the 1910s, it was very tough to locate verse that had withstood the test of time. And the 1980s has an odd paucity of publication.

But each of them also gives us some of our most exciting writers. So it was really important to do that footwork into archives and think about the scholarship that’s grown up around some of these questions.

I wish I could have included more music or, you know, children’s verse. There’s a huge tradition of Black verse for children. Hughes himself wrote in that. Someone like Marilyn Nelson, a terrific poet, writes beautiful children’s books.

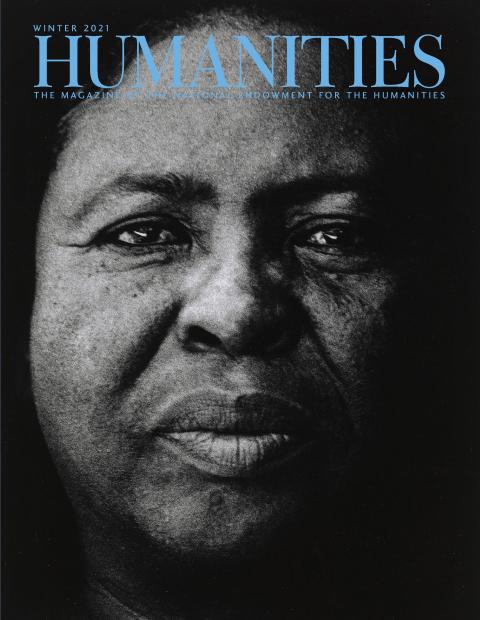

HUMANITIES: Tell me about your history with the poetry of Lucille Clifton. She’s something of a special figure for you, I gather.

YOUNG: Yes. She’s such a special person and poet. Her children’s books are outstanding too. I was just thinking of her because a lot of people post her New Year’s poems. She was a poet who wrote a poem at the turn of the year. She wrote poems on her birthday and then on her late mother’s birthday almost annually. So she was a poet of not just history, but of intimate history and of change.

She is also the person who in 1993 picked my first book to be published (it appeared two years later). I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for her. And back when I was at Emory University, where I was a curator, hers was the first archive I got. I helped get her papers there, and I, in fact, with help, packed them up myself. It was 100 boxes, 50 of books, 50 of papers.

By the time I left Emory for the Schomburg Center—11 years later, almost 12—it was the second or third most used collection there, amidst Irish and other poets, including Heaney. And, you know, I think in a weird way, her time still hasn’t come. I think she’s still being discovered over and over again, which is really exciting. And it was exciting to see her poetry being shared by people who aren’t poets at the turn of 2021.

She writes beautifully about everything from menopause, to being visited by a fox when she was experiencing cancer and surviving it, to the pleasures of the body and the pleasures of language. She writes about things that I think we all move through and live through but don’t always have the words for.

HUMANITIES: I did some counting of the number of poems and pages devoted to various poets. Langston Hughes gets a lot of pages, which didn’t surprise me. Gwendolyn Brooks gets just about as many. But the living poet Sonia Sanchez seems to get the most pages. One, is there a canon of Black poetry you wanted to expound? And what can you say about the prominence of Sonia Sanchez?

YOUNG: Sister Sonia—I’m surely not alone in thinking she’s one of the great poets of our time. She’s still with us, writing terrifically. And I’ve had the pleasure of seeing her read during quarantine. Being on Zooms when she’s reading, it just takes your head off.

Canon-building is not really interesting to me, per se. I’m more interested in how people read and providing people an archive they might not otherwise see, especially right now. An archive for your pocket when you can’t go into an archive.

In some ways the anthology does that: You can read it and stay in it, but I also think it sends you back out into the world.

If it helps you pick up any of Sister Sonia’s books from We a BaddDDD People to Does Your House Have Lions? to Shake Loose My Skin, any of her books, then great.

Sister Sonia’s poems about the MOVE bombing are really powerful. And they were prescient. No one was saying, you know, you must write a poem about MOVE. Instead, she’s saying this is an injustice, I want to talk about it. She’s another poet writing about things that now we see are the heart of the matter, events that may have seemed like isolated incidents at the time but go to the heart of the struggle.

HUMANITIES: So you are becoming the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened just a few years ago to ecstatic reviews. What are your plans for this already famous museum?

YOUNG: First, I want to get to know it and see it from the inside, but I think one of the exciting things about the museum is the way it is already providing people a look at their history and the history of African Americans, which is at the center of American history.

We opened in the fall for a little bit, as did other parts of the Smithsonian, but right now the Smithsonian, like many places, is closed to visitors given the pandemic.

One of my goals is to look at how we’ve already done a lot of digital outreach, and to continue with that and build it up and think about the digital future, which is really the digital present.

There are also definitely going to be more acquisitions. They help people see that history is alive. And there are still things to discover in what we have at the museum already.

I’m looking to think about how we can interpret these new trails for people, but also provide them a way of encountering them on their own. I think the museum does both of those things better than anyone, and so it’s incredibly exciting to be there, at the center of African American and American history.