On June 22, 2020, protesters attempted to take down an equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson that had stood in front of the White House for 167 years. Typical of media coverage of this event, a National Public Radio story explained why the protesters targeted the seventh president: “President Jackson, who was a Tennessee slaveholder, signed into law the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which led to the expulsion of Native Americans east of the Mississippi River. The Cherokees’ forced march to Oklahoma, during which thousands died, became known as the Trail of Tears.” This brief narrative encapsulated what journalists, the educated public, and many U.S. historians know about Indian removal. Andrew Jackson was responsible for the policy. The Cherokees were its main victims.

This story is too simple. Although Jackson’s top priority upon becoming president in 1829 was to secure removal legislation, by his own admission, the Indian Removal Act was the “happy consummation” of a policy “pursued for nearly 30 years.” Jackson likely had in mind Thomas Jefferson’s advocacy of relocating Indigenous nations. When Jefferson purchased Louisiana from France in 1803, he declared that the new territory would “give establishment in it to the Indians on the east side of the Mississippi, in exchange for their present country.” Another problem with singling out Jackson is that he was no longer in office during the Cherokee Trail of Tears. It was Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, who oversaw the death of thousands of Cherokees forced west in 1838–39. This, of course, does not get Jackson off the hook. He agitated to evict the Cherokees during his entire presidency. An exclusive focus on Old Hickory, however, gives the erroneous impression that removal was the brainchild of a single, particularly bad president. In fact, the removal of Indigenous people was a national priority with broad consensus.

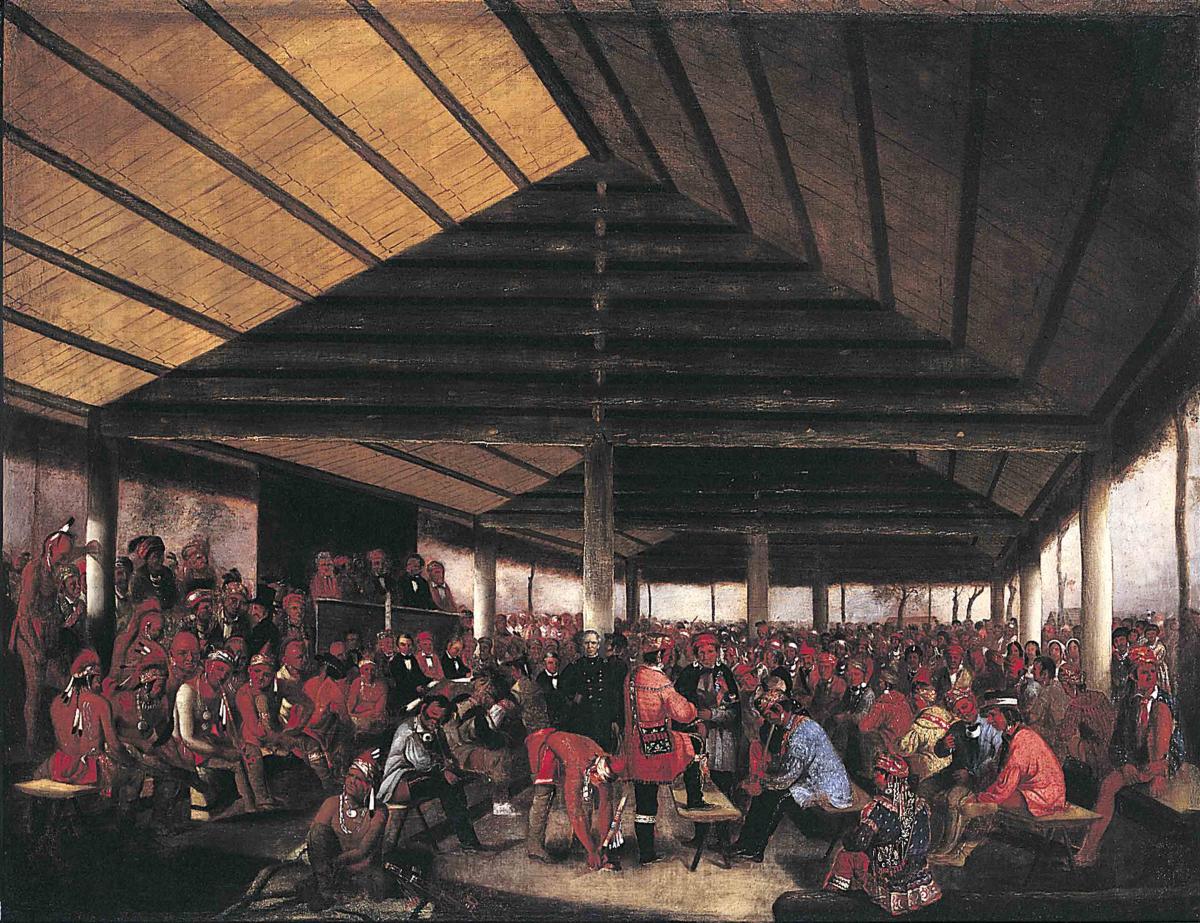

Often, the consensus behind removal has been obscured by conflict over the passage of the Indian Removal Act. Many Americans, especially in the North, opposed the legislation. One leading opponent was Jeremiah Evarts, a Protestant missionary, who wrote a series of essays under the pen name William Penn. Evarts powerfully argued that forcing the Cherokees from their homelands violated Christian principles. Catharine Beecher, a leading reformer in Hartford, Connecticut, took up the cause and encouraged women to petition Congress against the legislation. The removal bill passed the Senate comfortably (28 to 19), but the margin in the House was slender (102 to 97). Many who voted against the legislation worried it would damage a Christian nation’s honor, though some were motivated more by political animosity toward Jackson.

Historians have speculated that had removal legislation failed in 1830, the United States might have taken a very different path and allowed Cherokees (and other Indigenous nations) to remain in their homelands. Even if the vote had gone the other way, however, Jackson and his allies, most notably the state of Georgia, would have continued to push for removal. Opposition would have remained, but it probably would have weakened over time. Most opponents of the 1830 legislation were not completely against removal. Their main objection was to the coercive methods Georgia was using to evict the Cherokees. These included passing laws aggressively asserting jurisdiction over the Cherokee Nation, despite its treaties with the federal government, and allowing Georgia settlers to take up Cherokee lands. Missionaries and others who supported the Cherokees believed that the Cherokees would eventually have to move west. They wanted Cherokees to freely assent to this prospect. The only people who were unalterably opposed to Cherokee removal were the Cherokees themselves. In an “Address to the People of the United States,” the Cherokee National Council informed its audience that “if we are compelled to leave our country, we see nothing but ruin before us.”

It is understandable that narratives about removal have focused on the Cherokees. Not only were they central to the debates about the Indian Removal Act, they remained in the spotlight when they filed suit before the Supreme Court, challenging Georgia’s laws that undermined their treaty rights. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation was, in the words of Chief Justice John Marshall, a “domestic dependent nation.” As such, it did not have standing before the Court and could not challenge Georgia’s laws attacking Cherokee sovereignty. The Cherokees then used Georgia’s arrest of the missionary Samuel Worcester, who had been residing inside the Cherokee Nation, to return to the Supreme Court. As a U.S. citizen, Worcester had standing before the Court. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia’s laws undermining Cherokee sovereignty were unconstitutional, a great victory for the Cherokees and an important precedent in American Indian law to this day. Soon, however, Cherokees realized that the chief executive would not enforce the Court’s decision (Jackson supposedly said, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it”). A majority of Cherokees, under the leadership of Principal Chief John Ross, tried to fight off removal, but a minority, led by John Ridge, signed a removal treaty in 1835. This ignited another national debate as the Senate considered ratification. Even though the treaty clearly did not have the support of the Cherokee Nation, the Senate ratified it by a vote of 31 to 15, one more than the necessary two-thirds majority. The treaty, which was ratified in 1836, gave the Cherokees two years to move to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The army began rounding up 19,000 Cherokees in May 1838. Around 2,000 died from measles, dysentery, and fevers in detention camps that summer before their journey west had even begun. Over the next several months, between 2,000 and 3,000 more perished on the way to Indian Territory and shortly after their arrival.

The Cherokee Nation’s heroic fight against removal, its implications for American Indian law, and the suffering and loss of life on their trail of tears are all an integral part of any history of Indian removal. Nonetheless, the Cherokees were far from the only nation to be targeted for removal. College-level textbooks often point out that in addition to the Cherokees, the other major southeastern nations (Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles) were also forced from their homelands during the 1830s. Their trails of tears were just as horrific. But textbooks generally ignore the many nations in the North who were also removed. Reflecting a blind spot among U.S. historians, Jill Lepore in her magisterial These Truths: A History of the United States erroneously states that the policy of Indian removal “applied only to the South.” In fact, all or portions of the following northern nations were evicted in the 1830s and 1840s: Delawares (Lenapes), Haudenosaunees, Ho-Chunks, Kickapoos, Miamis, Ojibwes, Ottawas, Potawatomis, Sauks and Mesquakies, Shawnees, and Wyandots.

Recognizing that removal affected all Indigenous nations east of the Mississippi River is important for two reasons. First, it counters a tendency to locate America’s evils primarily in the South. It is true, of course, that what the 1619 Project terms America’s “original sin” of slavery was centered in the South (though slavery continued to be legal in many northern states into the early nineteenth century). But America’s other “original sin”—removal and the violent dispossession of Indigenous peoples more broadly—was not limited to the South. From the time of the American Revolution, taking Native lands was a national priority. Second, a full accounting of the impact of removal requires us to consider not only the consequences for the Cherokee Nation and the other southeastern nations but for the northern nations as well. There were many, many trails of tears.

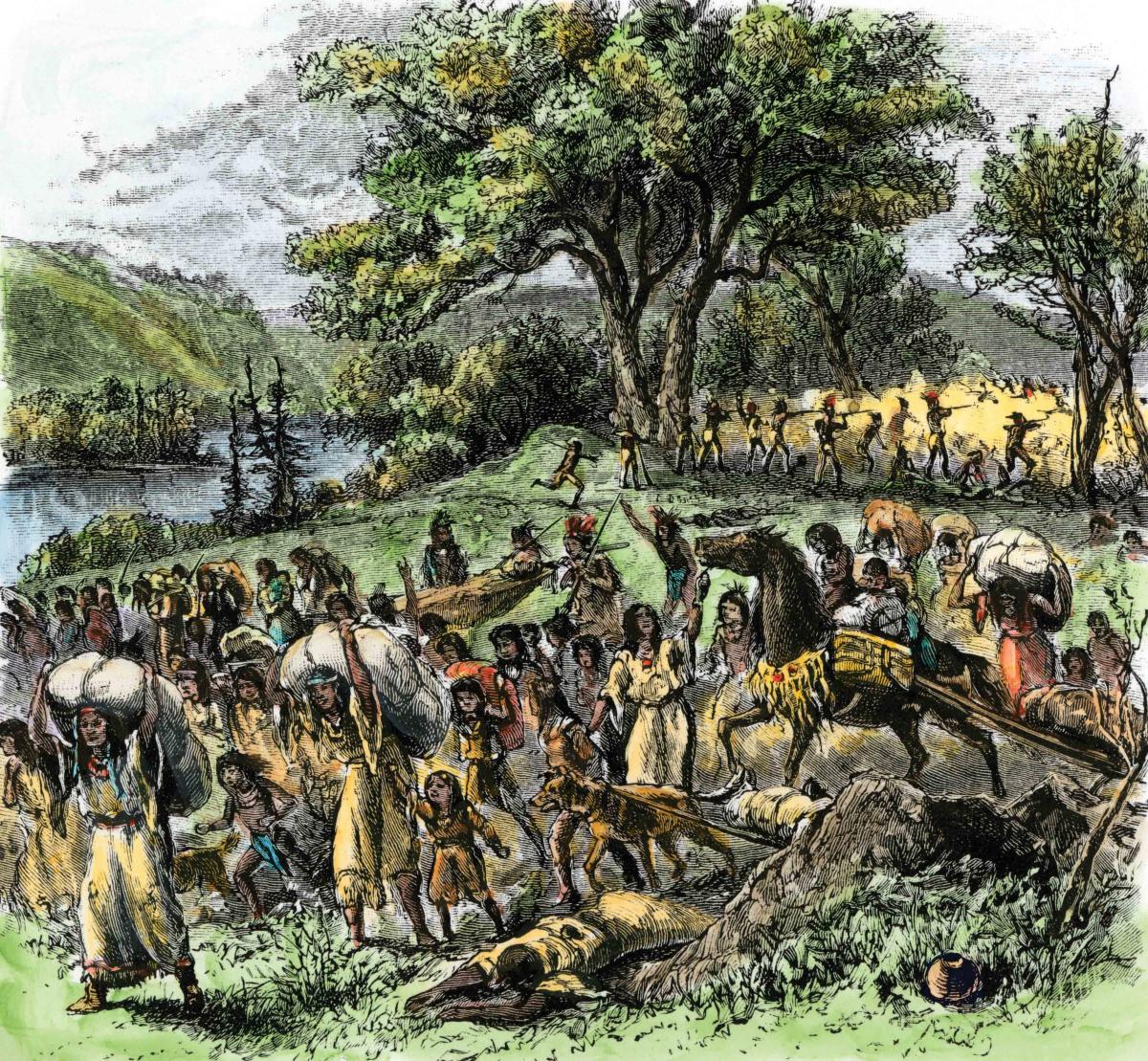

Consider the Sauks and Mesquakies (Foxes), nations that had united in the early eighteenth century to survive genocidal violence from the French and their Indigenous allies. After the passage of the Indian Removal Act, federal officials demanded that the Sauks and Mesquakies vacate their villages on the east bank of the Mississippi River in Illinois. Under the leadership of Black Hawk, a minority resisted this demand. When they did, the Army forced them to leave. To evade federal troops (joined by Illinois militiamen and Menominee, Ho-Chunk, and Dakota auxiliaries), Black Hawk and several hundred followers fled north into Wisconsin. After several weeks on the run, many in Black Hawk’s band had perished from starvation. With troops still in pursuit, the remainder, now at the mouth of the Bad Axe River, tried to escape by crossing the Mississippi into Iowa. As they did, soldiers aboard a U.S. steamboat, bearing the name Warrior, came up the Mississippi and fired a cannon and other guns at men, women, and children on makeshift rafts, swimming alone, or with horses. At the same time, the pursuing troops arrived and cut down people still on the riverbank. The death toll in the August 1832 Bad Axe massacre was around 260.

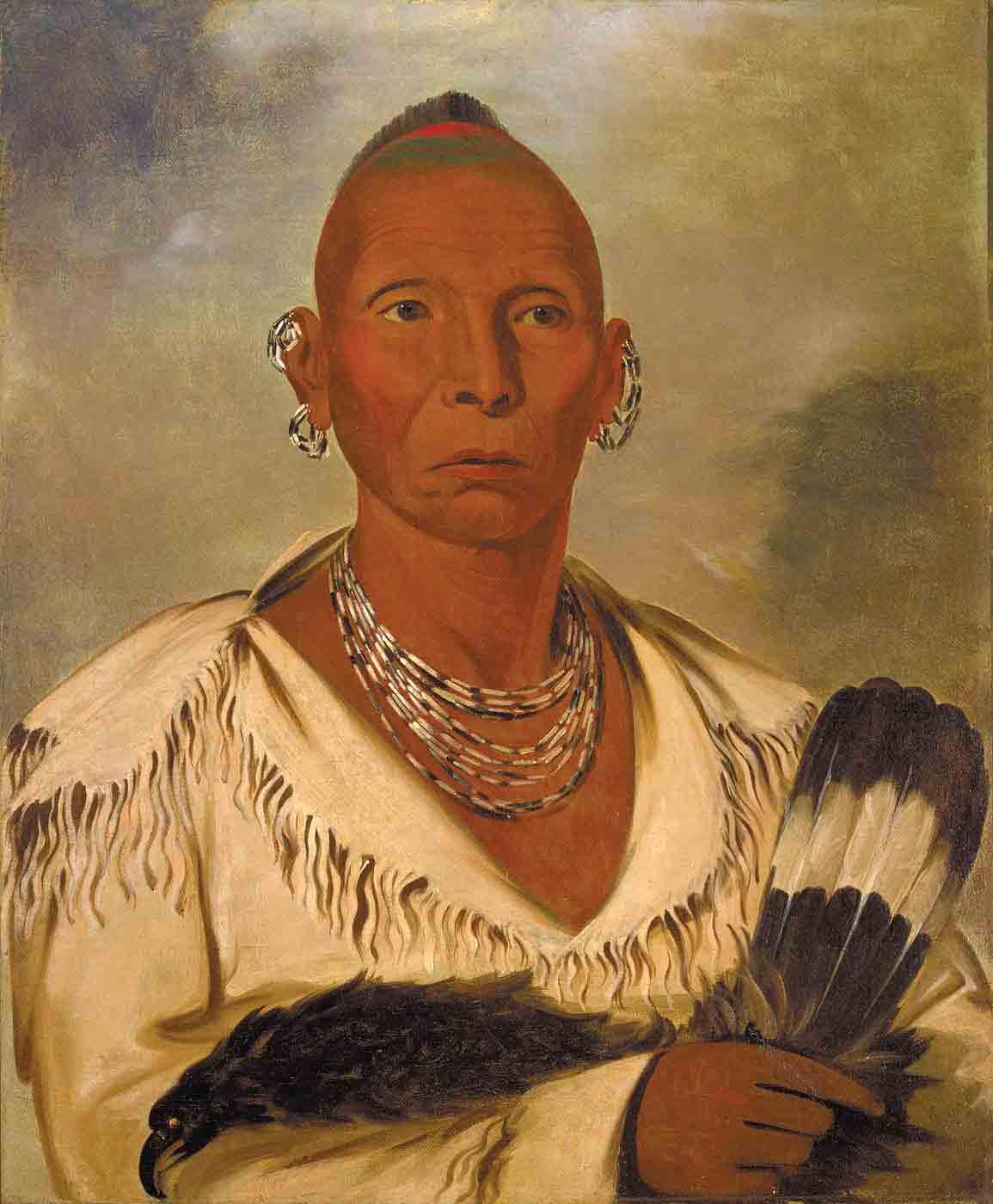

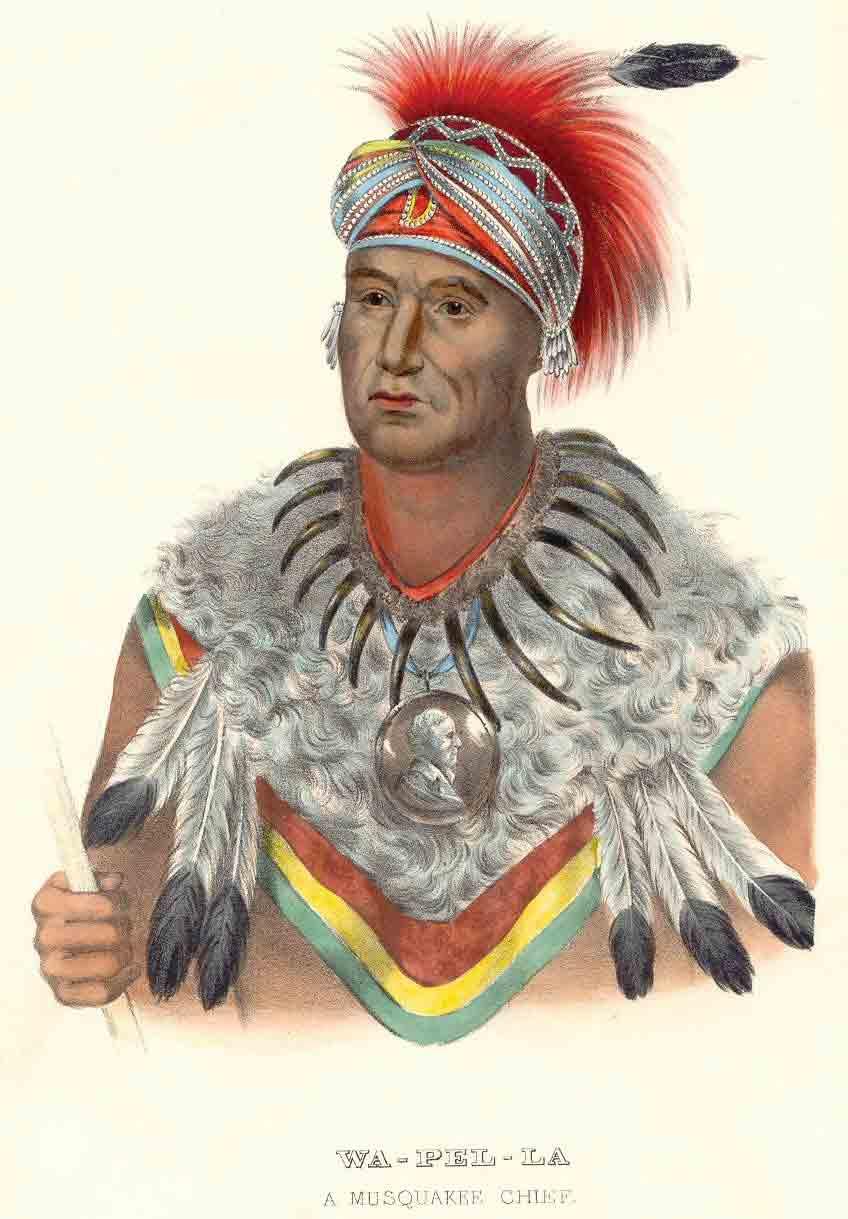

U.S. military action forced the Sauks and Mesquakies to move into eastern Iowa (a small removal), but their ordeal had just begun. Not surprisingly, Americans soon began to desire lands in what would become the Hawkeye State. Federal officials decreed that Sauks and Mesquakies would need to move again, but they could not figure out a place to send them. So, in 1842, the government moved the Sauks and Mesquakies to a temporary location in western Iowa, which lacked timber and good soil and was infested with mosquitoes. Finally, in 1846, well over a decade after being ordered out of Illinois, federal officials designated a small reservation in eastern Kansas for their “permanent home.” Year after year, as Sauks and Mesquakies suffered from starvation, malnutrition, exposure, social stress, and disease, their population steadily diminished. From 6,500 in 1830, they numbered only 3,000 in 1846. “We are but few, and are fast melting away,” Mesquakie chief Wapello told U.S. officials.

It took only eight years for a new wave of settlers to threaten the Sauks and Mesquakies’ supposedly permanent home in Kansas. The trigger was the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which led two competing groups of Americans to invade Kansas, one hoping to organize Kansas as a free state, the other hoping to organize it as a slave state. The ensuing violence between pro- and anti-slavery settlers, known as “Bleeding Kansas,” is a crucial chapter in the coming of the Civil War, but few historians think much about the Indigenous nations living there. The Sauks and Mesquakies suffered far more than the contending Americans. In 1854, they numbered just over 2,000. Six years later, as hunger, malnutrition, and disease continued to destroy bodies and inhibit reproduction, their population had fallen to a mere 1,280, their population reduced in three decades by 80 percent. After the Civil War, the United States moved the Sauks and Mesquakies yet again, this time onto a small reservation in Oklahoma. This, their fourth removal, was fortunately their last.

Another blind spot in our understanding of Indian removal is the neglect of the policy’s impact on Indigenous nations in areas west of the Mississippi River. The trails of tears did not end in an empty wilderness waiting to be settled. They ended in the homelands of Ioways, Otoe-Missourias, Kanzas, and Osages. To make room for the removed eastern nations, the United States dispossessed and relocated these Indigenous nations. Take, for example, the Osage Nation. In the early 1800s, the Osages, for decades the most powerful people in the region, controlled territory that included southern Missouri, northwestern Arkansas, northeastern Oklahoma, and southeastern Kansas. Anticipating the removal of eastern nations, in 1825, the United States imposed a treaty on the Osages that ceded all of their lands except for a narrow strip in southern Kansas. For more than a decade, Osages successfully resisted leaving their villages in northeastern Oklahoma. After the arrival of Cherokee survivors of their trail of tears in 1838–39, however, the Osages decided they had no choice but to move to their Kansas reservation. This was not a great distance, so few people died during the move. But conditions on this much smaller reservation were not conducive to Osage well-being. Up until this time, the Osage population had been stable, but through a process of slow attrition, their population shrank from between 5,000 and 6,000 in the late 1830s to 3,500 in 1857. The causes were the same as for the Sauks and Mesquakies: malnutrition, exposure, and social stress, which made people vulnerable to multiple diseases. These same factors reduced fertility and hindered demographic recovery. Also dispossessed, Ioways, Kanzas, and Oto-Missourias suffered similar losses.

The Cherokee Trail of Tears was bad enough. When we take into account the fact that the U.S. policy of removal affected dozens of nations throughout the East and significant parts of the Midwest, it becomes clear that Indian removal was worse—far worse—than we usually realize. All told, about 88,000 people indigenous to the eastern United States were forcibly moved west of the Mississippi River in the 1830s and 1840s. Between 12,000 and 17,000 perished while being rounded up, detained, and on the journeys west. This was a death toll of between 14 and 19 percent. To put this in perspective, the COVID-19 pandemic has so far taken the lives of slightly over 1 million Americans from a population of 330 million, slightly less than .3 percent. Imagine that the United States had suffered a similar death toll from COVID as Indigenous people did from removal. The loss would be between 46 and 62 million people. Then imagine that the U.S. population continued to crater after the pandemic as health care systems crashed, food production declined, homelessness increased, and new diseases ravaged an already battered nation. This is analogous to what happened to most eastern nations after removal. It is also similar to what happened to nations whose homelands were west of the Mississippi.

What is the best name for a policy with such catastrophic consequences? In recent years, many historians have described Indian removal as ethnic cleansing. This represents a significant indictment of the United States, since ethnic cleansing includes practices—such as forcible displacement of civilians—that are considered crimes under international law. On the other hand, the term ethnic cleansing, like the term removal itself, can seem euphemistic. Moreover, since ethnic cleansing can theoretically occur with little loss of life, applying the term to Indian removal doesn’t really capture the brutality and overall impact of the policy. Terms like eviction or deportation better convey its coerciveness, but they, too, do not necessarily make clear its dreadful consequences.

In my book Surviving Genocide, published in 2019, I proposed that the policy should be classified as genocide. The first step in my analysis was fairly straightforward: The policy clearly had genocidal consequences. The next step, a more complicated one, was to address the issue of intent. Andrew Jackson and other presidents and policymakers did not conceive of and implement removal for the purpose of killing people. In fact, their stated rationale for the policy was the direct opposite: to save Indigenous people from what they claimed was an inevitable fate to disappear if they remained where they were. The idea—a very self-serving one—was that Indigenous people surrounded by a supposedly superior white race were withering away. Indians would continue to vanish unless they were sent west, where they could progress toward “civilization” apart from the baleful influence of whites. At first glance, the fact that policymakers apparently intended their policy to be beneficial may seem to obviate an allegation of genocide. Had Andrew Jackson and other American leaders genuinely cared about preventing death, however, they would have listened to Cherokees who saw “nothing but ruin before us.” That they did not strongly suggests that their professions of benevolence were a fig leaf for their true intention: to eliminate Indigenous people, no matter the consequences. Furthermore, removal was not a one-off event. The policy of evicting eastern Indigenous people was carried out for two decades. This means that an evaluation of intent must consider policymakers’ response to the policy once it became clear that it was destroying communities. Had U.S. officials been genuinely concerned for Indigenous well-being, they would have halted the policy of removal once it became clear that it was having such destructive consequences. This they never considered. To continue to pursue a policy with genocidal consequences, I concluded, is to commit genocide.

One danger in labeling Indigenous history as genocide is that it risks reinscribing pernicious stereotypes of Native Americans as victims who no longer exist. In considering disastrous policies like Indian removal, then, we must not overlook that Native people survived the trails of tears and worked to rebuild their communities afterward. A good place to start is to remember that one of the most famous Native Americans of all time, Jim Thorpe, winner of two gold medals in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics and often considered the world’s greatest athlete, was a descendant of survivors of the Sauk and Mesquakie trails of tears. Today, the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma numbers more than 4,000, three times their 1860 population. (There are also two other smaller Sac and Fox nations, one in Iowa, the other in Kansas and Nebraska.) The Cherokee Nation has around 450,000 citizens, 25 times the number who survived their trail of tears. It is important, too, to realize that although most Indigenous people in the East were removed, a significant minority were not. These include nations that the United States never tried to evict: Lumbees in North Carolina, Shinnecocks on Long Island, Mashpees in Massachusetts, Abenakis in Maine, and many more. They also include portions of removed nations that successfully resisted or evaded removal: Seminoles in Florida, Cherokees in North Carolina, Miamis in Indiana, Potawatomis in Michigan, Haudenosaunees in upstate New York, and many others. Heroic survival and persistence should be celebrated as an essential part of the story of Indian removal.