“After de War I was what you call a freedman. De Indians had to give all dey slaves forty acres of land. I’se allus lived on dis land which jines dat of Ole master’s and I’se never stayed away from it long at a time.” Thus did Frances Banks, a formerly enslaved African American, describe herself and the situation for other formerly enslaved people in Indian Territory when interviewed by a Works Progress Administration (WPA) field worker in 1938.

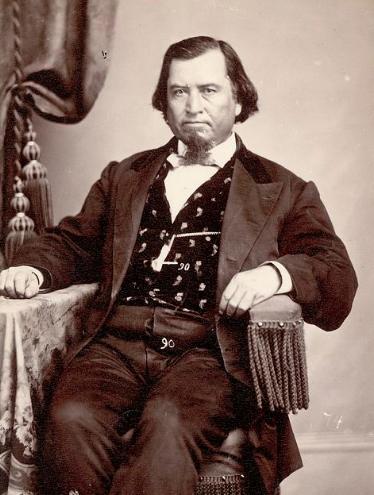

Banks was born on a farm near Doaksville in the southeastern corner of the Choctaw Nation before the Civil War. Her parents belonged to the Wright family, whose prominent members included Allen Wright, principal chief of the Choctaw Nation from 1866 to 1870, and later a judge by the same name in the state of Oklahoma. Her short interview—which, like many conducted with former slaves, was transcribed using stereotypical Black speech patterns—offers a provocative glimpse at slavery, the Civil War, and emancipation, all familiar subjects in American history, but from a less familiar vantage point: Indian Territory.

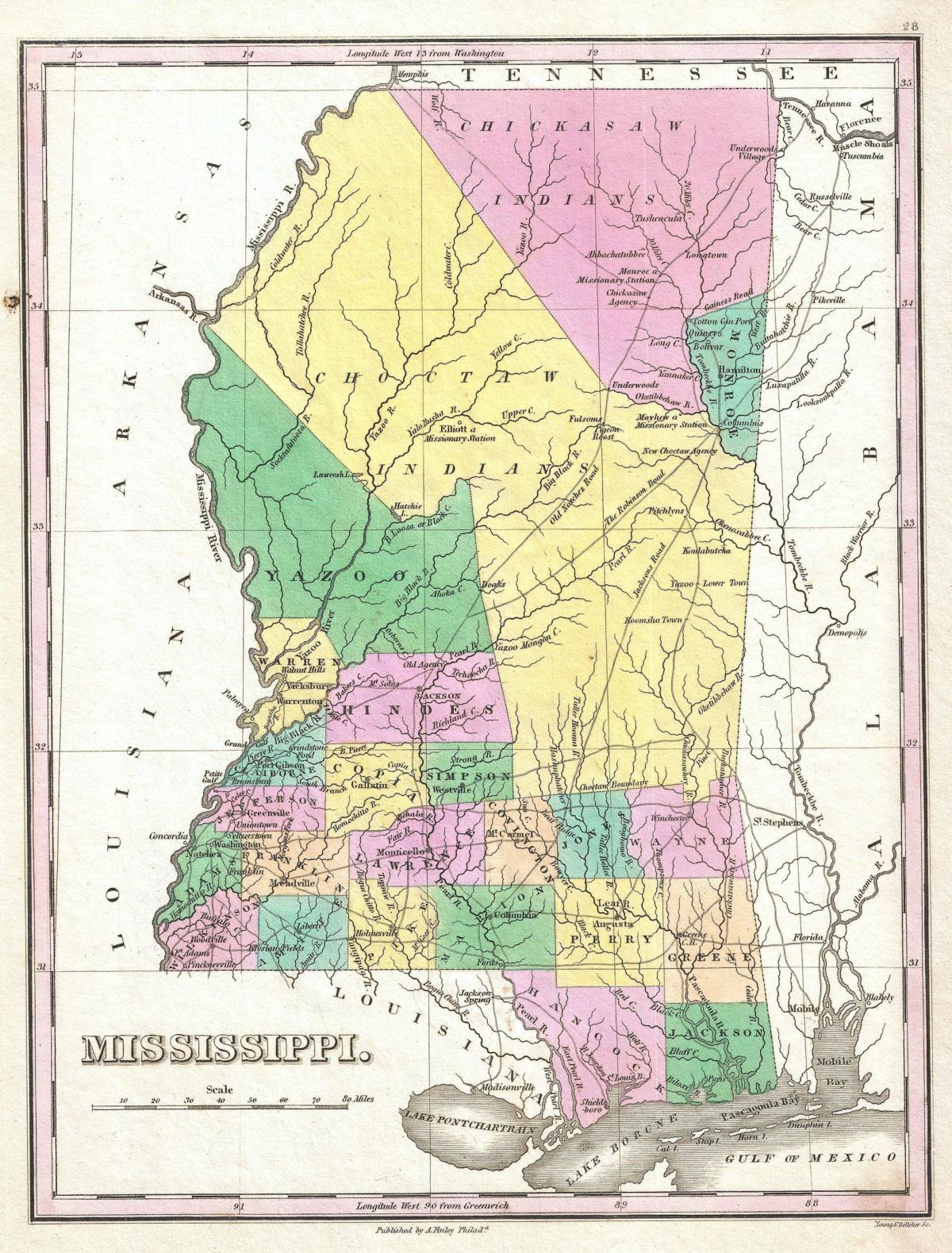

Although the term “enslaver,” for most Americans, is likely to conjure up the image of a white plantation owner, Native tribes such as the Choctaw also enslaved people of African descent and had done so for more than a century before the Civil War. European traders and settlers introduced the Choctaws to enslaved Africans as early as the 1720s. By 1831, a federal census conducted in preparation for removing Choctaw Indians from the Mississippi River Valley to Indian Territory enumerated 17,963 Indians, 151 white persons, and 521 enslaved people. Just eight years later in 1839, there were approximately 600 enslaved people of African descent living among the Choctaws. And by 1860, enslaved people of African descent made up 14 percent of the population in the Choctaw Nation. Enslaved people in the nation performed agricultural labor and, when fluent in both English and Choctaw languages, frequently served as interpreters for their Choctaw enslavers. Like their counterparts in the American South, Choctaw enslavers passed legislation that prevented enslaved people from owning property or carrying guns without permission and that prohibited the education of enslaved people. Additionally, Choctaw lawmakers prohibited marriage between enslaved people and Choctaw citizens.

People enslaved in the Choctaw Nation described to WPA interviewers labor routines, punishment, family life away from the eyes of their Native masters, and religious practices in terms that would be familiar to those who study slavery in the American South. Yet Choctaw Indians and other Native groups did not blindly adopt state laws regarding the behavior and treatment of enslaved people. Nor did they always engage in the same kind of commercial activity as their southern counterparts. Despite these differences, the Choctaw Nation had a vested interest in the perpetuation of slavery and the social order slavery created. For instance, some Choctaw enslavers engaged in large-scale plantation agriculture, produced corn, or raised cattle that would be consumed by enslaved people in nearby states. Moreover, the Native practice of enslaving people of African descent reminded white Americans that Native peoples should not themselves be enslaved as they had been in the colonial period.

Choctaw lawmakers and citizens watched with interest as tensions between so-called “slave” and “free” states (both states were, in reality, home to enslaved people) increased in the early nineteenth century. Following the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 and the ensuing forced displacement of the Choctaw from their homeland in Mississippi, the Choctaw were concerned that white settlers would further encroach upon their territory. In addition, the Choctaw received annuities from the federal government, so tribal members feared that a civil war could threaten their financial well-being.

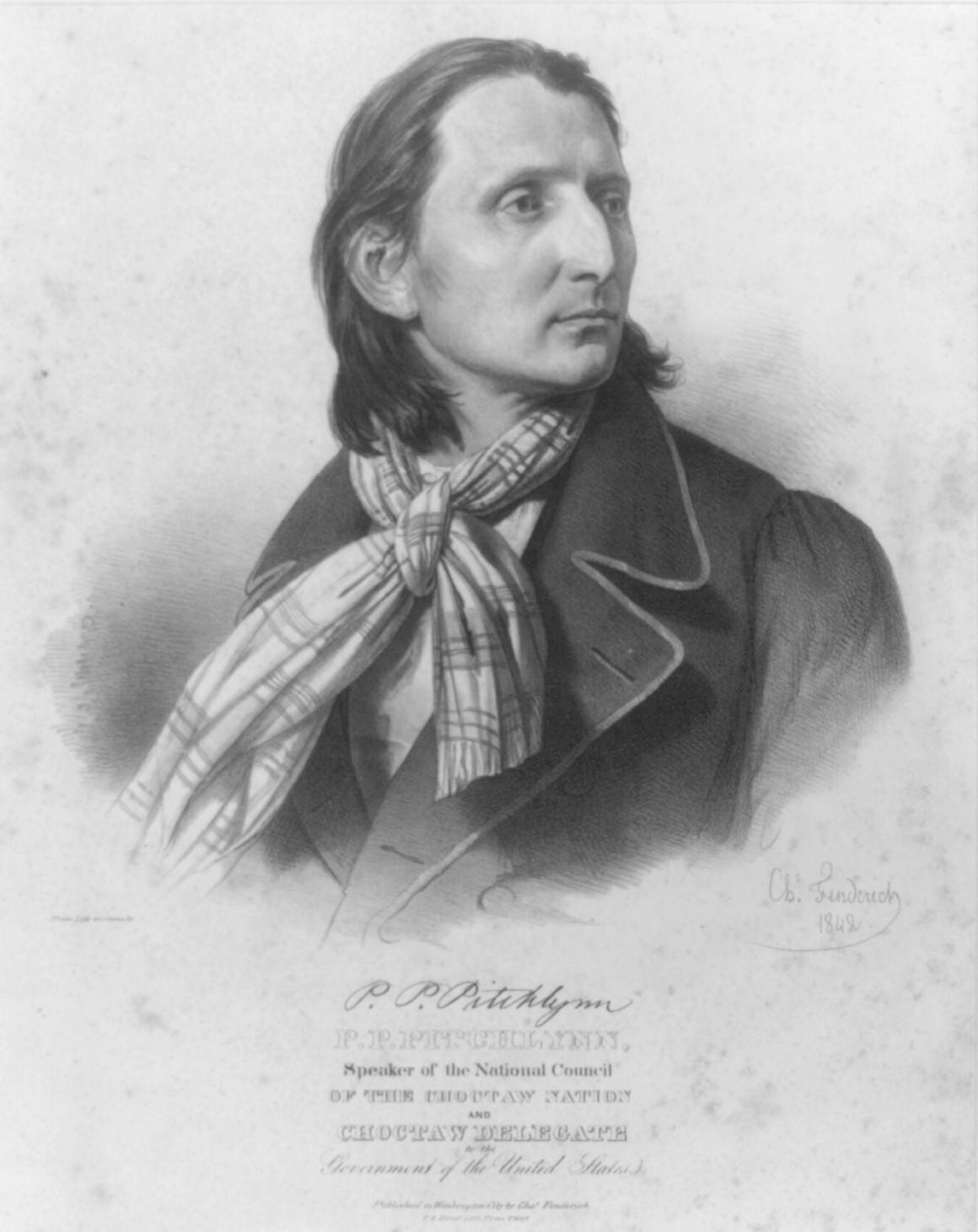

Once southern states started to secede after the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, southern officials rushed to secure the support of Native groups in Indian Territory. And those same Native groups felt neglected by federal authorities who would eventually pull troops from the region to focus on the war’s eastern theater. When a group of Texans received word of Choctaw legislative meetings, they attended to advocate for the southern cause. That pressure, however, was unnecessary. The Choctaw people shared many economic ties with southerners and recognized that the Confederate states’ argument for secession addressed two concerns for the Choctaws: protecting their right to own human property and buttressing their claims to sovereignty. Surely, the newly formed Confederate government could not profess to respect the sovereignty of each member state while denying the sovereignty of Indian nations. And the constitution of the newly formed Confederate States of America included clear protections for the institution of slavery.

The outcome of the Civil War, then, mattered not just to enslavers and the enslaved in the United States but to those in Indian Territory as well. Some 100 Choctaw men flocked to enlist in the Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment to aid in the Confederate cause even before the Choctaws had negotiated an official treaty of alliance with the Confederate government, and more than 1,000 men enlisted as mounted riflemen in 1861 alone. Officials from the newly formed Confederate government offered all kinds of inducements to secure the Choctaws’ allegiance: to honor the treaties the Choctaws had already made with the federal government; to pay for military expenditures incurred by the Choctaw Nation in the war effort; and perhaps most importantly, to protect Choctaw sovereignty. But the Choctaw men who served found many of these promises were hollow. Often supplies and money never arrived from the Confederate congress. So, despite being described by Confederate officials as their most loyal allies in Indian Territory, Choctaws lost their enthusiasm for the war, and enlistments dropped off.

After the end of the Civil War, people who had been enslaved by Choctaw Indians, and in the Indian Territory more generally, experienced emancipation and Reconstruction. Formerly enslaved people described emancipation in language very similar to that used in the accounts of formerly enslaved people in the United States. In one respect their experiences were quite different: The Black people who had been held in bondage by Native peoples in Indian Territory gained rights to land, though only 40-acre plots rather than the communal ownership of all land that Choctaws enjoyed, while formerly enslaved people of the southern states did not. Property ownership, however, did not necessarily improve the political or legal status of the freedmen in Indian Territory. Choctaw officials opposed the extension of full citizenship rights to freedpeople—such as the right to hold political offices in the Choctaw Nation, the right to annuity funds, and the ability to confer Choctaw citizenship on others through marriage—almost as fiercely as many white southerners did.

The treaty agreements reached to reestablish relations between the federal government and states and Indian nations during Reconstruction continue to reverberate today: Descendants of Choctaw freedpeople currently cannot obtain citizenship in the Choctaw Nation unless they demonstrate descent from an individual enrolled by the Dawes Commission as a “blood” member of the Choctaw Nation. (Congress established the Dawes Commission to enumerate people living in Indian Territory in preparation for allotting Native land into 160-acre parcels for heads of households and smaller plots for individuals. The federal government then sold surplus land for white settlement with funds to be held for Native education.) Similar citizenship requirements have led some descendants of those who labored under Indigenous enslavers—specifically in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations—to pursue legal action to gain full citizenship rights in their respective nations. Had Native governments made different decisions about citizenship for formerly enslaved people during Reconstruction, perhaps these issues would not be contested today. Just as in the nineteenth century, the issue of citizenship for formerly enslaved people and their descendants in Indigenous nations continues to raise uncomfortable questions about governmental authority, Native sovereignty, and race.

Ultimately, the decision of Indigenous groups to side with the Confederacy in an effort to preserve their autonomy provided a justification for further dismantling Native sovereignty. The consequence of this decision was even more enduring and consequential than it seemed. It not only reconfigured the place of people of African descent within Native societies, but also shaped the future relationship of Native peoples to the federal government.