A familiar serenity hangs over the welcoming green campus of Berea College in southeast Kentucky. The students are busy and preoccupied. The architecture is Georgian and neoclassical. It might be a thousand other colleges, but in many ways Berea is like no other school in America.

Its president is a critic of political correctness. Its faculty act in loco parentis. And self-indulgence is strongly discouraged among the student body. For these and other reasons, Berea can seem like a standing rebuke to various trends in American colleges today.

Students pay no tuition and every single one of them is enrolled in a work-study program. The school doesn’t even have a football team, and yet the sense of community is quite strong. Like a lot of colleges, Berea was founded to educate a specific population: poor whites and both free and enslaved blacks—a radical arrangement in 1850s Kentucky. Unlike a lot of colleges, the moral and political thrust of its original mission is still in evidence.

Berea also boasts many of those qualities of soul and character that education critics such as William Deresiewicz and others complain are missing from the upper echelons of college education. To get a sense of what all of this looked like up close, I visited Berea for several days last fall.

My first morning I met Jordan Sims, a senior majoring in African-American studies and minoring in business and music. Sims is from urban Lexington and is the first in his family to attend college. He had never heard of the college and assumed Berea was just “some random hillbilly town.”

As we walked to his morning class, Sims said that when he first arrived, he was shocked to learn that his instructors wanted relationships outside the classroom. “They actually knew who I was,” he said. “They checked in to make sure I was doing okay throughout my freshman year.” Though he had been offered a scholarship at Kentucky State, Sims is confident he made the right decision to come to Berea. “This is the only school for me,” he said. “I wouldn’t have succeeded elsewhere.”

Berea’s idiosyncrasies and demanding schedule can inspire panic among incoming students, but Sims, who wants to be a professional R&B singer and start his own record label, said it was “impossible not to succeed because of the amount of help offered by the faculty. I’ve built the strongest relationships of my life here, with friends and teachers both.”

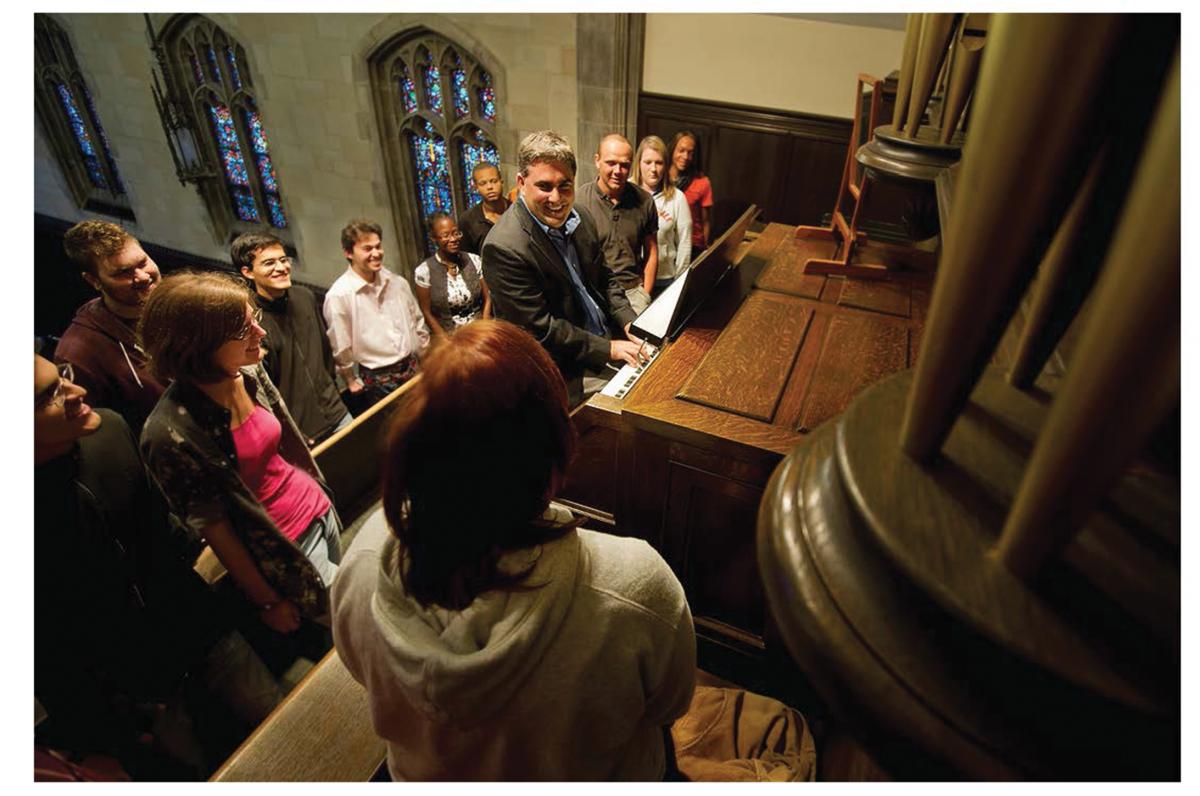

Later that morning I met Javier Clavere, a burly Argentine who teaches music theory and semiotics. After twenty-five years as a concert performer and music instructor in New York, he was looking for more holistic teaching opportunities when he heard about Berea’s mission to serve the underprivileged. Clavere, who rose from a modest background himself, says he “wept in disbelief.” Confronted with a freshman class that largely couldn’t read music—“Only rich kids get piano lessons,” Clavere says—he had to adapt his teaching methods to suit their needs. But now he reports a steep learning curve made possible by “getting them to believe they can do it.”

Emily Franklin, one of Clavere’s students, is a junior of modest means who was raised in tiny Sligo, Kentucky. Franklin’s father had warned her that his financial support would end upon her graduation from high school. She was leery of taking out loans and, so, needed to either win a scholarship (like most here, she was in the top 10 percent of her class) or enter the job market, but then she heard about Berea.

An eager teaching assistant in Clavere’s music department, Franklin calls the school’s labor program a “brilliant idea that introduces you to real life, which is crazy hectic.” Adding up her commitments, she says, “class, work, singing practice, friends, sports, convocations; it’s a full schedule, constantly, but it really helps you learn to plan your time and work really, really hard.”

Talking to Clavere, I heard about another important duty of Berea’s faculty, one of pastoral care. Many of Clavere’s Appalachian students, he says, come to Berea with a lack of familial support for their studies. As I know from personal experience, in some rural areas academics are viewed with disdain. Ambitious students are considered effete or uppity and said to be “getting above their raising.” Clavere says he has heard horror stories of kids being persecuted at home and, as a result, dropping out, all the more reason it is important for Berea to create a communal atmosphere and insulate students from fiscal worries.

Active in the student counseling offered by the campus Christian center, Clavere, whose wife, Lindsay, is also on the music faculty, says that the semi-parental unit they offer has been a great comfort to students with recurrent personal problems. “They do become,” he says, “like our children.”

Opened in 1855, the same year John Brown’s fighting abolitionists took on pro-slavery militias for control of “Bleeding Kansas,” the college was first housed in a one-room cabin. Its founder, Rev. John G. Fee, the son of a slave-owner, was an evangelical prohibitionist and abolitionist. He used the New Testament to argue, in theory and in practice, for the free and equal education of all Americans regardless of gender, race, or condition of servitude.

He took as his mottos two particularly democratic lines from Scripture: “Thou shalt love the Lord your God with all thy heart; . . . and thy neighbor as thyself” (Luke 10:27) and “Do unto others what thou would have them do unto thee” (Matthew 7:12).

Fee’s refusal to accept that women and blacks were inherently inferior attracted the notice of the great Kentucky statesman and emancipation advocate Cassius Clay, who provided Fee with ten acres of hilly farmland south of Lexington. Four years later, pro-slavery vigilantes, fearful that the new school’s teachings could inspire a slave uprising, drove the faculty and students from the county.

Fee spent the Civil War years in Ohio raising money for his school and promptly returned in January of 1866 to restart the institution as a bastion of “antislavery, anti-caste, anti-rum, [and] anti-sin” education, open to all who proclaimed their allegiance to Berea’s central tenet: “God has made of one blood all the peoples of the earth” (Acts 17:26).

As an institution, Berea always sought to operate according to the Christian doctrine of impartial love, but in 1904 the Kentucky legislature passed the Day Law, which prohibited interracial education. This law was typical of the Jim Crow reactionary politics then sweeping the South. Berea fought the law, however, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Berea College v. Commonwealth of Kentucky (1908) held that the state, having incorporated Berea, retained the right to alter its charter as it chose, and that the college could continue its education of blacks so long as it did so in a separate facility. The dissent of Justice John Marshall Harlan, a Kentuckian, faulted the Court for favoring a state’s right to enforce segregation over the individual citizen’s right to due process under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Berea’s president at the time, William Goodell Frost, tried to make the best of a bad situation by focusing the school’s resources on a policy he had adopted a few years previously: using the college to try to raise the living standards and educational opportunities of the entire Appalachian region.

A New Yorker by birth, Frost took a nuanced view of Appalachians, whom he once described as “religious, truthful, hospitable, and much addicted to killing one another.” He saw the mountaineers of his adopted home as the natural allies of Berea’s mission. Unionist, antislavery, Republican, possessed of a strong work ethic and the capacity to succeed under the most trying of conditions, the people of Appalachia were to Frost “a glorious national asset,” a means of providing “the South what it has always lacked, a sturdy middle class.” He believed that from the ruins of the antebellum cotton aristocracy a new South of Christian principles and equal opportunity would spring forth. And this new South would be led and epitomized by the people of Appalachia.

In response to the Supreme Court’s ruling, the college’s trustees set out to fund the construction of a new facility near Louisville so as to comply with state law, and in 1912 the Lincoln Institute opened as an all-black school. Sadly, it lacked the collegiate department that distinguished Berea and therefore offered a distinctly lesser educational opportunity.

Frost lacked the legal and perhaps personal capacity to carry on the inclusive vision of John Fee, either by moving Berea north or by somehow resisting the courts and maintaining integration through subterfuge. Faced with a ruthless legal dictate, he did what he could to maintain the college’s mission, channeling Fee’s vision of equality away from racial diversity and toward the nearby white population that also needed it. His dedication to Berea’s integrative mission was, however, evidently sincere; he is said to have requested that his heart be buried at the Lincoln Institute.

At my next meeting, with the school’s current president, Lyle Roelofs, Frost’s name comes up several times. It is clear that Frost’s abandonment of racial integration remains a sore subject, despite the fact that Berea at the time had no legal alternatives.

President Roelofs describes himself to me as a “liberal evangelical.” He sees Berea’s mission as a form of “liberation theology” and bemoans the paucity of religious influence in today’s liberal arts curricula. He is quick to disassociate the inclusivity of Berea’s campus from prevalent notions of political correctness, observing that Berea “is not about tolerance, but about learning from each other. This is the essence of a liberal arts education.”

Today Berea’s student body numbers 1,623, representing forty-eight states and fifty-eight different countries. About two thirds of the students hail from the nine states that make up the southern and central Appalachian region. For them, college amounts to a crash course in interpersonal, interregional, and international acclimatization. For a kid who has never strayed from southern West Virginia or eastern Tennessee, the prospect of rooming with a student from Cleveland or Tangiers must appear similarly exotic.

As the average amount of debt carried by college graduates steadily rises, Berea students’ debt has actually decreased. With its $1 billion endowment, Berea regards its students not as an income stream but as a regional investment.

The school welcomes nontraditional students such as single parents and the elderly, so long as they meet the school’s formal prerequisites of proven financial need, academic excellence, and a record of community service. The average household income of incoming students is around $27,000, with 99 percent eligible for federal Pell grants. Students earn between $12 and $24 an hour in the school’s labor program, and these welcome funds are often channeled back home as room, board, and essential books are all provided.

Berea seeks out prominent scholars from across the world for its faculty, but the college maintains its dedication to serving its native region through the Appalachian Seminar and Tour, a weeklong sojourn into the nearby hills for incoming instructors unfamiliar with the backgrounds of so many of their new students. The program includes a two-day colloquium exploring the region’s history, economics, politics, religion, stereotypes, medical care, and other relevant issues, followed by five days of travel. Previous itineraries have included examinations of mountaintop removal, traditional arts, health and nutrition, paleontological discoveries, and regional filmmaking.

Achieving tenure is a matter of assembling a teaching record illustrative of Berea’s core values: excellence in instruction, immersive scholarship, active mentoring, and service to the college and the community. Lacking the frantic “publish or perish” culture so numbingly familiar in American education, the faculty is freed to concentrate on the demanding work of providing an exceptional education.

Faculty members are quick to say that these mountain kids deserve nothing less, but the teacher-student relationship is not all warm and fuzzy. There is no time for dalliance or self-pity here, and laggards are quickly shown the door. “Berea doesn’t need you,” was how one instructor put it.

Rob Foster has taught the history of East Asia here for eighteen years. Berea students, he says, have a hunger to achieve and to make the most of college that he hasn’t seen at other schools. A PhD from Harvard, Foster says it is the “no-nonsense enthusiasm” of his students that keeps him happily at Berea.

“Our message to students is that anything is possible,” he said. “With our Socratic emphasis on critical thinking we try to make them lifelong learners.” Like many of the faculty I met, Foster is an ardent interdisciplinarian, mixing the minutiae of the Song Dynasty with a love for categorizing the migratory songbirds in the college’s 8,400-acre managed forest. He also leads students on scuba ventures to Honduras to survey Caribbean coral reefs, now under threat from climate change.

An English professor, Jason Cohen describes Berea as a “place of possibility.” He says the essence of his work can be found in his approach to Shakespeare as a universal language, appreciable even by students with little or no previous exposure to the Bard. Cohen also coteaches a course about the ethics of being a neighbor, a project that connects Berea with the American University of Cairo. Working together, students at the two institutions communally explore the basis of civic duty amid the European interest in Orientalism sparked by Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, “obligation as a condition of neighboring” as explored in Antony and Cleopatra, and the fallout of the Arab Spring through readings from Kant and Hannah Arendt.

Cohen insists on “close and slow reading,” with three hours of personal study for every hour of classwork. Whether exploring the etymological and philological roots of Hamletor what he calls the “dubious distinction” of Shakespeare’s centrality to the Western curriculum, Cohen echoes his fellow faculty in insisting that each student give his or her all, all the time. “Their call is to work,” he says, “and to not give in.”

It may seem like a simple thing for a professor to go on the record speaking well of his employer, but there is a unique intensity to the sense of mission at Berea, where the discussion always returns, with an extra dose of passion, to these people and this region.

“Berea is the center of the Appalachian universe,” says Academic Vice President Chad Berry while sitting on the sunny porch outside his office. “Traditional Appalachian schools act as conduits out of Appalachia,” he adds. “Our challenge is to make education not ‘up and out’ but ‘up and back,’ so students can bring back to their hometowns the lessons they’ve learned here.” Berry notes proudly that 60 percent of Appalachian Berea grads remain in their home territory, an extraordinary rate of success given that leaving the mountains has long been the dominant pattern for educated whites.

Berea has a Chair in Appalachian Studies (supported originally by a major grant from NEH). It is currently held by the popular Kentucky novelist and environmental advocate Silas House. During a recent class, House was discussing the demographic “eclecticism” of Appalachia, home to Shawnee, Cherokee, and Mingo before settlement by the Scotch-Irish, then further diversified with the influx of Eastern Europeans and blacks who came to work in the coal mines.

“There are many Appalachias,” House intoned that afternoon in his heavy Southern Midland accent, bound together in the stifling “mono-economy” of coal production. A true son of the mountains whose own grandfather died of black lung disease, House views the coal and gas industries as mere takers, wholly uninterested in the lives and working conditions of their employees. He pointed to the persistent fatalism that grips the region, the limited economic opportunities, an apocalyptic religious tradition, poor health and nutrition, and the high rates of suicide and drug abuse.

“Appalachia represents both the best and the worst of America,” House declared later that afternoon, its culture simultaneously "romanticized and vilified” through heartless stereotypes that could hardly be applied to any other ethnic or cultural group. House recalled a brutal event in southwest Virginia a decade previous that I remembered well. A three-year-old boy named Jeremy Davidson was crushed to death in his sleep by a boulder dislodged from a nearby strip mine. House asserts that had this tragedy occurred in any community other than the depopulated, perishable society that is Appalachia the media coverage would have been fierce and lasting.

House feels that his mission is permeated by an “insistent insistence on dialog” to undo the pervasive harms of the past and point the way toward a more hopeful and sustainable future for Appalachia. Much as William Goodell Frost had hoped for, House is identifying ways for this continuously displaced people to take heart from their heritage and remake the mountains as a source of national pride. Clearly the spirit and strength of John Fee inspires House to work toward a better life for this most denigrated and ignored region of the country.

Like many visitors, I came away from Berea moved by its daily dedication to the idealistic mission of equal opportunity. I had deeply enjoyed my own education down the road at Centre, but I realized that it had come at a price that few of these students could afford. Berea College, founded over 150 years ago in a blaze of democratic activism rooted in our highest ideals, continues to provide deserving students with a rigorous education in a nurturing atmosphere of “learning, labor, and service.”