In spring 1855, a man walked into the office of a newspaper called the Empire in Sydney, Australia, with an unusual request: He wanted to borrow a “correct copy” of the United States Constitution and Richard Hildreth’s recently completed History of the United States. In “a style of speech decidedly American,” the “respectably dressed” person gave a “modestly expressed apology,” presumably for causing any inconvenience. The office buzzed, work stopped, and the daily routine of getting out the paper was broken as all eyes turned to the greater “novelty” unfolding before them. For the person, one editor wrote, was not simply an American but an American “man of colour”—though his “complexion would be hardly noticeable among the average specimens of the English face.” In admitting that the man could pass as white, the editor inadvertently revealed that it was only by noting other details that they were able to read him as Black. Invisible to the eye, these details pressed upon other senses, above all the ear. Something in his “manner” led them to read him as Black, but, more important, as a man not to be taken lightly.

By jamming their ordinary modes of knowing the world, the stranger was making an example of himself. And in so doing, he was artfully training them to dignify his Blackness. He drew his audience’s attention to his cultivation, evident in his clothes and the way he wore them, the way he moved, expressed emotion, modulated his voice, chose his words. For these white Australians, as for the white audiences he had performed before in New England, New York, and aboard ships and in goldfields around the world, his sophistication made him mysterious. What could explain how this man had come to seem “intelligent on almost any subject,” “appear at ease in any society,” and speak with a “fluency and depth of interest scarcely excelled by any of his predecessors—even by [Frederick] Douglass himself?” And how had this American come to Australia, of all places?

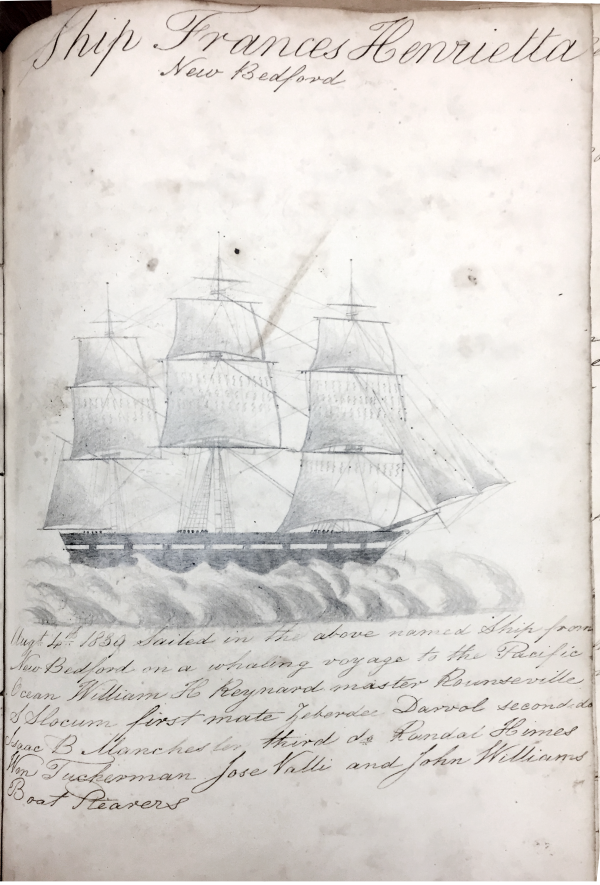

With “bright intelligent eyes” and a “gentle firm voice,” he patiently answered their questions, gaining respect and drawing them in, until they found themselves listening with “abiding interest,” hungry for more information. How he had attained his powers was not their chief concern, for these were newspapermen, on the lookout not for narratives of education and uplift but for a story that sold. And this man was just that: a story. Staying one step ahead of them and knowing from long experience how it would play, he revealed that he was a capital F, capital S, “Fugitive Slave,” who had come to Australia and succeeded in the gold rush that had followed California’s and who was now about to go to sea. For almost all his remaining life, from 1856, when he sailed for England, until 1872, when he returned to America at the end of his life, he would be in constant motion, sailing to every corner of the world, spending three hundred-plus days a year on the water, touching solid ground only briefly at far-flung ports like Elsinore and St. Petersburg, Constantinople and Odessa, Bangkok and St. Kitts, even working in India for part of 1867. At that precise moment, in 1855, however, he was “engaged in writing out his experiences of American slavery.”

And so, in a matter of minutes, a Black man with no country walked into the office of the leading newspaper in Sydney and not only disarmed the editorial staff but so intrigued them that they were persuaded to do something much more than lend out a few books. They agreed to publish his life story.

***

We don’t know whether John Swanson Jacobs mentioned that he called Frederick Douglass a friend and ally and had five years before lectured alongside him as a rising star in the antislavery movement. And we can only assume that he didn’t mention his sister, Harriet Ann Jacobs, who was still five years away from finding a publisher for her landmark autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, as she had been unable to find a suitably famous white abolitionist to edit, introduce, and legitimize her book, a virtual prerequisite for Black authors to publish in the transatlantic abolitionist world (she would be rejected at least three times before summoning up the courage to approach Lydia Maria Child). But we can be sure about one thing: The Empire editors were not ready for what was coming to them.

Two weeks later, Jacobs returned with a manuscript with a truly awe-inspiring title: The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots: A True Story of Slavery. By citing the six hundred thousand slave-owning Americans in his title, instead of the three million enslaved people more commonly mentioned by abolitionists, Jacobs announces from the start that his will be no standard slave narrative. Rather than make himself into an example of the horrors of slavery, Jacobs turns his life into an arc of refusal. And what he refuses is America itself. Not only does his autobiography zero in on the stark injustice of owning humans, concentrating his dazzling intellectual and emotional powers into casting his Blackness against this sharpest of white backgrounds, but it does so for a higher end: to prove that slavery and white supremacy are written into the conceptual bedrock of the American republic, starting with the Constitution, the “bulwark of American slavery.”

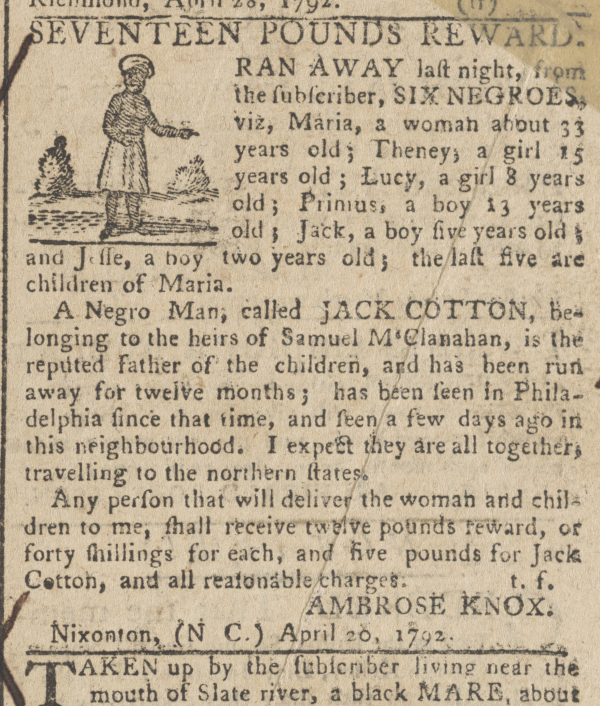

“The slave’s life is a lingering death,” he writes, and not simply because “six hundred thousand legalised robbers” operate a violent, abusive system of labor exploitation but because American law permits them to do so. And since the “law” is “the will of the people—a mirror to reflect a nation’s character,” Jacobs holds all American citizens, South and North, accountable for writing despotism—absolute rule over an unfree people—into a democratic charter. “That devil in sheepskin called the Constitution of the United States,” which “contains and tolerates the blackest code of laws in existence,” represents “the great chain that binds the north and south together, a union to rob and plunder the sons of Africa, a union cemented with human blood, and blackened with the guilt of 68 years.” Taking Jacobs at his word requires taking seriously political theorist Judith Shklar’s claim that, in 1776, the American nation “embarked upon two experiments simultaneously: one in democracy, the other in tyranny.”

Reading such rhetorically gifted, unapologetically defiant prose, it becomes clear that Jacobs’s performance for the Australian editors had been an act, an effort to ease open the doors to publication so that he could write with the righteous fury that his condition as a fugitive slave after 1850 demanded—but that no transatlantic antislavery publisher permitted. Although he was a stateless refugee and migrant laborer, Jacobs was able to find a forum to print his narrative that did not come with the usual strings attached. He did not have to accept the indignity of giving a white ghostwriter free rein over his words as a condition of publication. Neither did he have to festoon his narrative with certificates of good character solicited from notable white abolitionists, nor pay the psychic tax levied on Black Americans when forced to choose between expressing righteous anger over the injustices of the world or remaining silent in the hopes of improving their lot. In choosing to make a forthright profession of his hatred of slavery, in a style that dissolves the false but widely held opposition between rage and reason, Jacobs turned an unenviable situation to his advantage, using it to demonstrate that his own unfiltered, unedited words could stand as proof of his self-worth.

It is to the editors’ credit that they “scarcely altered a word” of Jacobs’s manuscript other than correcting spelling and adding punctuation. Consequently, the recovery of Despots gives us an unprecedented chance to understand how, outside American law and humanitarian authority, African Americans reconfigured the relationship between liberty and truth. While the promise of gaining direct access to the “mind of a slave” through unedited texts has made handwritten manuscripts of autobiographical slave narratives into a holy grail for some scholars, Despots reveals that there is something more precious still: an unfiltered text. The rediscovery and republication of this lost autobiography represents the first opportunity to reckon with John Swanson Jacobs. Beyond the reach of American power, Jacobs speaks truth to American power, in a life story built on the conviction that words can ring so true as to build new worlds, a conviction that Jacobs and Douglass shared: “Yours for the truth,” he writes to his friend.

And yet even as Jacobs found that he enjoyed greater freedom of speech in Australia than in the United States or United Kingdom, his story was forgotten. In 1860, he would try to find an audience once again, submitting a copy of Despots to a London magazine called the Leisure Hour before leaving on a voyage to Rio de Janeiro, where an epidemic of yellow fever swept through the ship’s crew, killing two, hospitalizing Jacobs. On returning to London, how crestfallen must he have been to find his once powerful narrative chopped in half, censored and rewritten, and published under a sanitized title, A True Tale of Slavery? At about half the word count, the 1861 version contains about sixty paragraphs in common; of these, a handful are identical, while the rest are censored, rearranged, and reworded. The entire legal critique is eliminated, and the text is recomposed as a relatively conventional autobiographical slave narrative. Until now, that declawed version has been the primary means by which the public has come to know Jacobs.

***

The following is drawn from Jacobs’s autobiography, The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots: A True Story of Slavery, and is selected because it epitomizes Jacobs’s unfiltered, unapologetic truth-to-power style. The volume also features a full-length biography, No Longer Yours: The Lives of John Swanson Jacobs, which can be read alongside his autobiography.

I was born in Edenton, North Carolina, one of the oldest States in the Union, and had five different owners in 18 years. My first owner was Miss Penelope Hanablue, the invalid daughter of an innkeeper. After her death I became the property of her mother. My only sister was given to a niece of hers and daughter of Dr. James A. Norcom.

My father and mother were slaves. I have a very slight recollection of my mother who died when I was quite young, though my father made impressions on my mind in childhood that can never be forgotten. I should do my dear old grandmother injustice did I not mention her too; for there was too great a difference between her meekness and my father’s fury, though slavery had caused it.

To be a man and not to be—a father without authority—a husband and no protector—is far pleasanter to dream of than to experience.

Such is the condition of every slave throughout the United States; he owns nothing—he can claim nothing. His wife is not his—his children are not his; they can be taken from him, and sold at any minute, as far as the fleshmonger may see fit to carry them. Slaves are recognised as property by the law and can own nothing except at the consent of their masters. A slave’s wife or daughter may be insulted before his eyes with impunity; he himself may be called on to torture them, and dare not refuse. To raise his hand in their defence, is death by the law. He must bear all things and resist nothing. If he leaves his master’s premises at any time without a written permit, he is liable to be flogged; yet they say we are happy and contented. I will admit that slaves are sometimes cheerful; they sing and dance, as it is natural for any one to do when placed in their position. I myself had changed owners four times before I could see the policy of this. My father taught me to hate slavery; but forgot to teach me how to conceal my hatred.

The deepest impression ever made on my mind was by my father when I was about 7 years old. Mrs. Hanablue and himself one day called me at the same time.

I answered her call first, then my father’s. What his feelings could have been I know not, but his words were these—“John, whenever I call you again, come to me, I care not who else may call.”

“Sir, my mistress had called me.”

“If she is your mistress, I am your father.”

He said no more—it was enough—I knew the remainder—“Honour thy father and thy mother as the Lord thy God hath commanded thee, that thy days may be prolonged, and that it may go well with thee in the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.”

What has Slavery to say to this? Does she allow children to obey their parents? No: nor the God that created them, when it does not serve their ends. The doctrine they preach to slaves is blasphemy—telling them obedience to their earthly masters is obedience to God, and that they must be obedient servants here on earth if they ever hope to enjoy eternal life hereafter.

When a little boy, my father used to take me with him to the Methodist church. I continued to go, when I could, until one Mr. Moumon came there to preach; he preached to the whites in the morning, and to the slaves in the afternoon. His discourse to the slaves was invariably about robbing henhouses and keeping everything about your master’s house in good order. This is what they call religious instruction given to slaves. Not a Sunday school nor a Bible class throughout the south where a slave dare put his head in to learn anything for himself. It is unlawful for any one to teach him the alphabet, to give, sell, or lend him a Bible; yet they profess to be Christians they have churches, Bible and Tract Societies. They steal infants from their mothers to buy Bibles to send to heathens, and flog women to unpaid toil, to support their churches. This is what they do for the glory of God and the good of souls.

In 1850, I was in one of the railway coaches going from Boston Mass to Rochester N.Y. There were several ministers in the coach that had been to Boston to attend the missionary meeting, where the slave question had been discussed. Two of their number were either cut off or cut themselves loose, to save them the trouble, for having said that slavery was anti-Christian. This was bringing things too near home. They were dealing in human flesh and as a matter of course must make it appear all right in the eyes of the world. Well the Bible is taken for it. They first prove that slavery existed in the days of Christ and the Apostles; secondly, their course was non-interference, and that it was their firm belief, that a man could be a slaveholder and yet a worthy member in a Christian Church. Knowing that these gentlemen professed to be of the latter opinion, I begged leave to ask a question, after having quoted these words, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.”

“Now, sir, will you tell me which of the two are the greatest sinners in the sight of God, those who bow down and worship the image of God carved out in wood or stone, or those who sell Christ in the shambles in a human being?”

Said he, “It depends altogether upon the light they have had on the subject.”

“Well, if the south has not had sufficient light on this subject, why send your missionaries from home while the people at home are in greater darkness than those to whom you send them?”

I could get no further answer from him. The fact is, there is more knaving than ignorance among them. A man that will sell his own offspring, which thousands of them have done, has shown himself unnatural enough to do anything. They admit that a negro has a soul, but it must be a very painful acknowledgment to a nation whose prejudices are so strong. Go into the free States, or rather the so-called free States, for there is not a spot in that country, from one end to the other, whence I could not be dragged into slavery. I begin at the schoolhouse, I suppose myself a father living in one of these so-called free States. We have town schools in the different wards, I am always ready to pay my tax to help support these schools, but when I send my children they are told, “We don’t keep school here for niggers.”

There is my poll-tax I have paid. Am I not allowed to vote? “No, we don’t allow niggers at the ballot box here.”

Having grown sick of such treatment, I take my wife and children and go in search of a State where they will treat us according to our behaviour and not our colour. I have paid my passage on the steamer. As soon as I step foot into the saloon, with my wife and children, I am told that “niggers are not allowed here.”

“But, sir, I have a cabin-ticket.”

“I don’t care for that, I tell you niggers are not allowed here.”

The boat lands. I go to an Hotel.

“Sir, can I be accommodated here?”

“Whom are you with?”

“No one but my family.”

“No, we don’t accommodate niggers here.”

I go to another, “Can I get supper and lodgings here to night?”

“Yes, yes,—walk in.”

The bell rings, I take my wife and children, and start for the tea room.

“Where are you going?”

“To supper, sir.”

“We don’t sit niggers down with white folks here.”

We will suppose the next day Sunday. The church-bells are ringing, and the cold reception we have met with hath made my heart sick and my life a burthen. What say you if we go to church? It is agreed on. We enter. In going down the aisle I am politely touched on the shoulder—“There is a seat in that corner for niggers.”

“Sir, my wife is a member of this sect, of good and regular standing in her own church. This being Communion-day, she wishes to be with you.”

“Oh, yes, brother; well, she must come this afternoon; we are going to take it this forenoon—this afternoon we will give it to the niggers.”

I will suppose one of my children dead. It has been christened in this church. I apply to the church for the privilege of burying my child in their ground.

“Oh no, that will never do; we cannot allow niggers to be buried with white folks.”

Poor foolish man! Here your reign of tyranny is over. Can you prevent us from entering the kingdom of heaven or the gates of hell with white folks? You follow us to the grave with your prejudices, but you can go no further.

When asked why we are treated thus, the answer is, “They are an ignorant, degraded race.” Why are we ignorant and degraded? Are not the avenues to knowledge closed against us, and we made to black your boots, scrape your chin, cook your food, and do the rest of your dirty work, or starve? Do we not see it everywhere staring us in the face, as plain as though it were written—“No admittance here for niggers.” True, your demoralising and brutalising process for three hundred and thirty-three years is enough to have unfitted us for society, but are you still afraid to give us and our sons an equal chance with you and yours? Yes, you see as clear as that king whose knees smote together with fear, from the writing on the wall, that ignorance is the only hope of slavery, that to enlighten the slaves would be to liberate them.

Reprinted with permission from The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots: A True Story of Slavery by John Swanson Jacobs and edited by Jonathan D. S. Schroeder, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2024 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved.