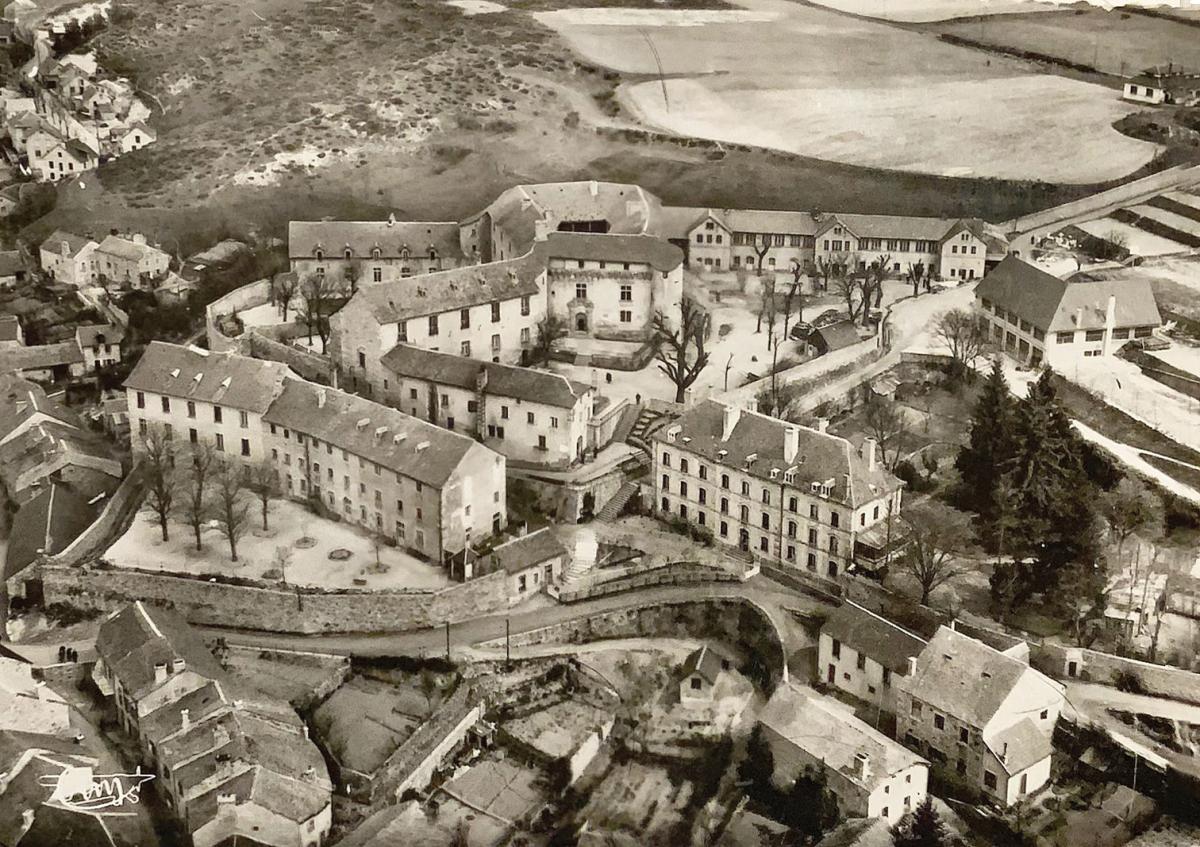

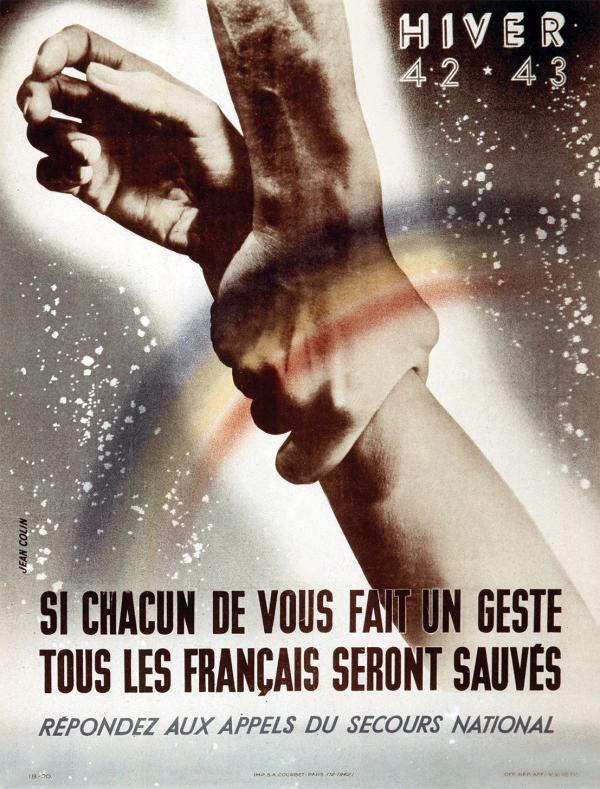

From 1940 to 1945, during the German occupation of France, 40,000 patients died in French psychiatric hospitals. Like much of the French territory during these years, hospitals suffered greatly from the war and the chronic shortage of food, medicine, and heat. These deaths, however, were not simply due to scarcity and strenuous living conditions, as official authorities contended, but to a specific policy of extermination of the cognitively disabled that the Nazi state promoted and the Vichy regime silently endorsed. Unlike the Third Reich, which actively embraced eugenics and the forced euthanasia of the “incurably sick,” the Vichy regime opted for a “soft extermination” that would let patients die of cold, starvation, or lack of care within the confines of the hospitals themselves. In Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, a small and isolated village in the Lozère, in central France, one psychiatric hospital attempted to resist and feed its patients by hoarding food with the help of the local population.

Alongside these efforts to provide sustenance and basic care, the doctors and the staff who worked at Saint-Alban began to rethink the practical and theoretical bases of psychiatric care. Fascism and the war had made clear the extent to which the political and the psychic were interconnected. Not only was the murder of the physically and mentally disabled central to the Nazi project of social regeneration, but fascism, authoritarianism, and collaboration were clearly not simple political choices: They required a particular state of mind. For the doctors at Saint-Alban, psychiatry needed to take into account this connection between the political and the psychic and fight on both fronts if it wanted to avoid being complicit with genocide. This movement, which began in Saint-Alban and had a significant influence on the world of psychiatry and postwar French thought, came to be known as institutional psychotherapy. My book, Disalienation: Politics, Philosophy, and Radical Psychiatry in Postwar France, traces the history of institutional psychotherapy and brings to light the importance of psychiatry for some of the best-known thinkers in twentieth-century France, including Michel Foucault, Frantz Fanon, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Georges Canguilhem.

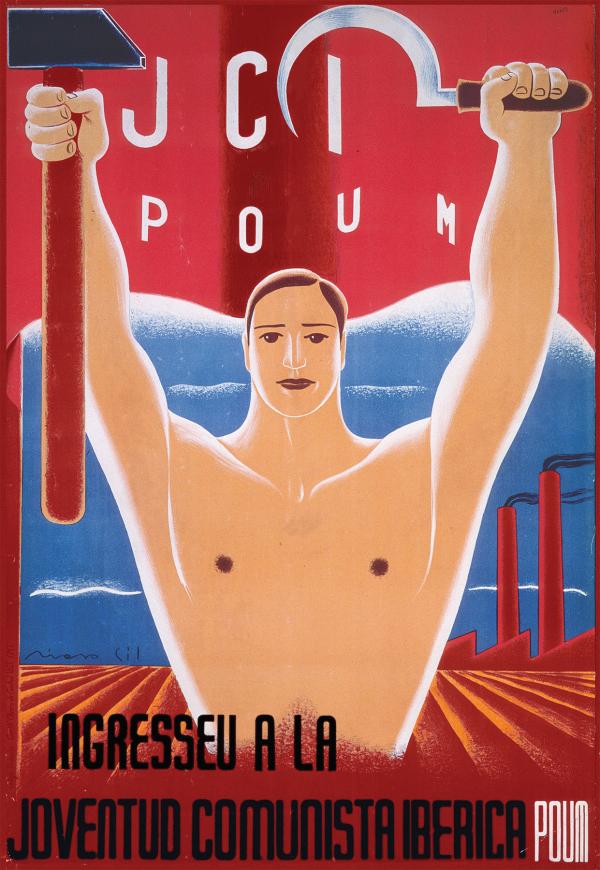

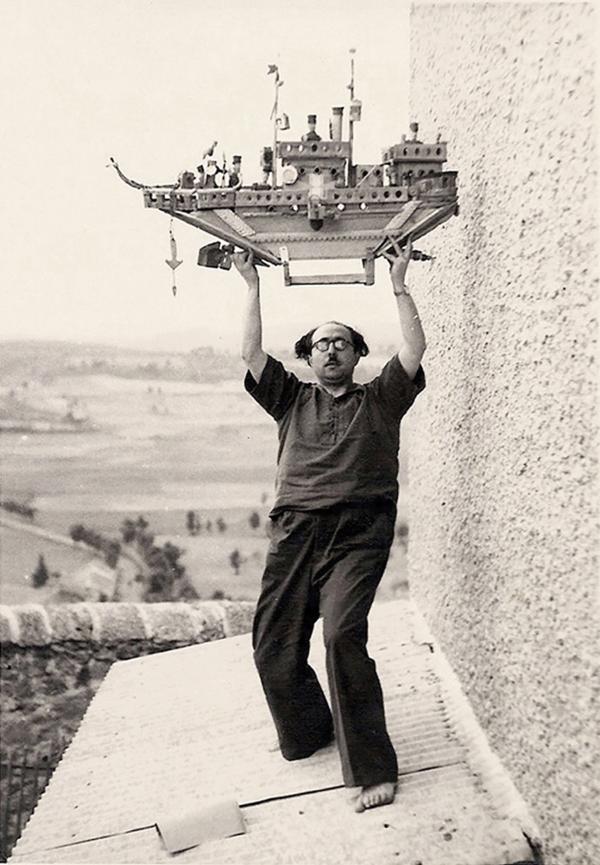

Less well known, but perhaps the most important theorizer and practitioner of institutional psychotherapy, was François Tosquelles, a Catalan psychiatrist born in Reus, south of Barcelona, in 1912. During his student years, Tosquelles was deeply involved in the vibrant political and cultural effervescence of Barcelona of the interwar period. In particular, Tosquelles was one of the founding members of the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista), a political group on the left that advocated federalism and decentralization, worker solidarity and self-management, and consciousness-raising, particularly through culture. The POUM was adamant about its opposition to Stalinism and to the antidemocratic, authoritarian, and bureaucratic turn that the Soviet Union had taken. The POUM was equally critical of the PCE, the official Spanish Communist party, which, they believed, had become much too subservient to Moscow. As Tosquelles repeated throughout his life, the POUM and this experience with radical democratic politics taught him to be extremely wary of what he called the “all-power” (le tout-pouvoir): the potential of all institutions, all politics, and all social formations to become rigid, oppressive, and despotic. These political experiences fundamentally shaped Tosquelles’s psychiatric practice.

Parallel to his activism in the POUM, Tosquelles began medical school in 1927 and chose to specialize in psychiatry, a booming field at the time. Not only did psychiatric reform feature prominently in the Catalanist political project, but Barcelona was often called “little Vienna” because it had welcomed so many Jewish psychoanalyst exiles from Eastern Europe. Tosquelles’s mentor Emilio Mira y López held the first chair of psychiatry at the University of Barcelona and was one of the main popularizers of Freud’s thought in Spanish. It was through Mira that Tosquelles first discovered the work of Jacques Lacan, who remained a constant source of inspiration throughout his life and a major reference for institutional psychotherapy. For Tosquelles, Lacan’s early psychiatric work was pioneering not only for the concepts it put forth but also for its methodological and institutional consequences. As Lacan made clear in his 1932 doctoral thesis, On Paranoid Psychosis and Its Relation to the Personality, the discipline of psychiatry needed to stop obsessively searching for specifically neurological automatisms that might explain madness. Psychosis, Lacan argued, was not inscribed in a particular area of the brain. Instead, it needed to be understood in relation to the formation of a particular “personality.” In other words, psychosis was never purely biological, and it needed to be studied in relation to the patient’s childhood, the structures of the delirium, and the drives and intentions behind social behavior. To this end, Lacan suggested, psychiatry needed to turn to psychoanalysis and, more precisely, to Freud’s notion of the subject, a subject resulting from conscious and unconscious representations constructed in relation to others—that is, in relation to a social constellation. For Lacan and for Tosquelles, the social was key to understanding the individual self.

Lacan’s thesis was one of the few texts that Tosquelles brought with him to France, “across the Pyrenees” as he put it, when he fled Spain in 1939, after Franco’s final military victory put a tragic end to the civil war and to the Spanish Republic. Tosquelles had joined the Resistance against Franco through the POUM in 1936, and he was quickly sent to fight at the front, in Almodovar del Campo. It was there that Tosquelles tested many of the theories and practices that he later developed at Saint-Alban, notably the idea of treating the community as a whole, of healing institutions in addition to individuals. At the front, Tosquelles set up a therapeutic community to take care of the combatants who had been traumatized by the war but also the army officers and the doctors themselves. The experience of the war taught Tosquelles that psychiatry could be practiced anywhere, even in the most arduous conditions.

After his arrival, Tosquelles was placed in one of the many camps that the French government had built to house the 450,000 Spanish refugees who were arriving on French soil. France had offered to welcome these refugees, but the defeat of the French Popular Front in 1938, the economic crisis, the rise of xenophobia and anti-Semitism, and the looming war with Germany significantly complicated this promise.

Living conditions in the camps were dire. The refugees were amassed in over-crowded barracks surrounded by barbed wire, electrical projectors, and surveillance posts. They slept in haystacks, had little wood available for heat, and lived in deplorable sanitary conditions. Some died of hunger, disease, exhaustion; others went mad or were driven to suicide. This “concentrationist” or “carceral” environment, to quote Tosquelles, led him to set up a psychiatric service within the camp, where, once again, he tested many of his theoretical insights, notably concerning the healing effects of collective projects. He recruited other political activists, artists, and musicians to help him organize activities—concerts, theater productions, publications, but also group therapies—in the hope that these would temper the effects of this “camp psychosis.” As Tosquelles remembered: “There was only one psychiatric nurse; the rest were normal people. I think it is one of the place[s] where I conducted very good psychiatry, in this concentration camp, in the mud.” As he observed, even a concentration camp could become a healing environment if its social relations were reconfigured through these group endeavors.

News of Tosquelles’s work in the camp and at the front traveled in medical circles and eventually came to the attention of the director of Saint-Alban, who invited Tosquelles to join his medical team in January 1940. Tosquelles arrived at Saint-Alban, in the middle of the war, to find yet another form of “concentrationism” with the Vichy regime, the German occupation of France, and the crisis of excessive deaths in psychiatric hospitals. The first task of Tosquelles and his new colleagues was to survive the war. They sought to gather enough staples from the local villagers to feed the patients, but they also encouraged them to work in the fields and raise livestock. The war was absolutely central in bringing together the cast of characters who laid the foundations for institutional psychotherapy. These included fellow doctors (such as Lucien Bonnafé and Georges Daumézon) and nurses (like Marius Bonnet), many of whom had been involved in communist or anarchist politics before the war and most of whom had joined the Resistance against fascism. It also included visual artists and poets such as the surrealist writer Paul Éluard and the historian of science Georges Canguilhem, who spent a few weeks at Saint-Alban in 1944. For Éluard, surrealism and psychiatry shared a similar goal of rehumanizing madness and fighting against what he perceived as the “absurd order” of the world. For Canguilhem, many of the themes central to his doctoral thesis (which eventually became his book The Normal and the Pathological, published in 1943) closely resonated with Tosquelles’s reflections on the limits of objectivity in science, the relativity of norms, the social construction of diagnoses, and much more. Despite their different backgrounds, the doctors, artists, and philosophers of Saint-Alban shared a vision of psychiatry as a deeply political practice. They called for a “politics of madness” that would bring together neurology, psychology, psychoanalysis, phenomenology, aesthetics, and social and political theory. The point of institutional psychotherapy was never to devise a fixed dogma or a model that could be applied indiscriminately but rather to offer an “ethics” in Michel Foucault’s sense of the term—a practice of everyday life.

As Bonnafé later put it, the practice that developed at Saint-Alban needed to be understood as the coming together of two contexts, one medical and one political: “the resistance to the inhumanity of the psychiatric world” and the “resistance to the Nazi occupation and collaboration.” Institutional psychotherapy thus emerged as a “philosophy of the no” to cite Bonnafé, a “no” against the ideal of scientific neutrality, detachment, and objectivism still prevalent in mainstream psychiatry, but also, relatedly, a “no” against totalitarian politics and its biopolitical assault on the cognitively disabled. If madness was not reducible to the brain, then it also required social solutions. As the double meaning of the term aliénation in French suggested, alienation was a psychic state—being mad, insane—but also a social condition that left patients feeling estranged, trapped, and isolated from others. “Disalienation,” in other words, involved the “disalienation” of madness but also of the hospital, the psychiatric profession, and the community as a whole. This constant effort to “disalienate” social relations and individual psyches is perhaps the best definition of institutional psychotherapy. Or in the words of French psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Jean Oury, “institutional psychotherapy [was] the act of setting up all kinds of mechanisms to fight, every day, against that which can turn the whole collective towards a concentrationist or segregationist structure.”

By “mechanisms,” Oury was referring not only to the theoretical revamping of basic psychiatric notions but also to a series of very practical measures. These needed to begin at the level of architecture. At Saint-Alban, the first step was to demolish the walls of the asylum and, later, the walls that separated each cell. Along similar lines, the administration eliminated uniforms and medical blouses so that doctors, nurses, and patients were indistinguishable from one another. The goal was to explode fixed roles, to do away with the “look of an idle barrack or concentration camp,” but also to force the medical staff to think through the singularity of the patient and his illness. This effort to respect the individuality of each patient was put into effect from the minute he entered the hospital, where he was welcomed by a committee composed of doctors, nurses, and patients that would orient him around the hospital and explain the logistics of the treatment and daily life.

If the hospital was to function as a “healing collective,” then it needed to develop structures to produce or institute a new social system. One of the most important innovations was the “Club,” a patient-run cooperative structure, a sort of self-financed union in charge of organizing all activities within the hospital. The Club planned meals, theater and music performances, sports, parties, and field trips—social events that were deemed integral to the cure. It also ran the library and the different ergotherapy and work stations, which included pottery, painting, and woodwork. It coordinated the publication of the hospital journal, Trait d’union, which brought together theoretical, literary, and poetic texts, with drawings, recipes, advertisements, letters, and more. The content was informational, but the act of reading, for Tosquelles, was a way to link the patients to the broader world, a “hyphen,” literally a “line of union” (trait d’union) to the broader community. As one observer noted, the atmosphere at the Club resembled a lively café where everyone conversed all the time. The constant discussions and the decentralization were mechanisms to provide a “permanent guarantee against the reappearance of oppressive behaviors.” In many ways, the Club was reminiscent of the POUM: nonhierarchical, self-managed, organic, and thoroughly democratic.

The Club, the journal, and the activities at Saint-Alban were all designed to create a horizontal “collectivity”: a new space for transference—a “transferential constellation” as Tosquelles called it—which could serve as the basis for a different treatment of psychosis. Even though the patients received one-on-one psychoanalytic sessions with the doctors, they also were invited to participate in the general meetings, which had an explicit therapeutic goal. The meetings, which were attended by doctors, nurses, staff, and patients, were strictly anti-authoritarian, and everyone was invited to speak on any philosophical or personal topic. As Tosquelles explained, holding regular meetings was crucial “to fight against the authorities, the hierarchies, the habits, the local feudalisms, the corporatisms. Nothing should ever be obvious, everything is subject to discussion. Everybody must be consulted, everybody can decide. Not just for the sake of democracy, but in order to facilitate the progressive conquest of speech, to learn mutual respect. The patients must be able to have a say on the conditions of their stay and their care, their rights of exchanges, expression, and circulation.”

The Club and the meetings were designed to fight stagnation and to foster a new form of common life. Once again, Tosquelles’s medical reflections resonated with his political engagements prior to the war. Institutional psychotherapy was also a form of permanent critique, what he called a “permanent revolution”: “the work that transforms an establishment of care into an institution, a healing team into a collective, is never finished. It requires the elaboration of material and social means, the conscious and unconscious conditions of psychotherapy.” And this, Tosquelles continued, was not simply in the hands of doctors and specialists. Rather, “it was the result of a complex assemblage [agencement] in which the patients themselves play a primordial role.” Today, even as mainstream psychiatry appears to be moving more decidedly toward neuroscience, pharmacology, and cognitive behavior therapies, rather than toward the revalorization of the unconscious, several young psychiatrists and psychoanalysts in France and abroad have returned to institutional psychotherapy to find concrete practices that will help alter psychic dynamics sufficiently to allow patients to imagine themselves anew and begin to heal.

As Tosquelles and his colleagues at Saint-Alban made clear in their written work and in their psychiatric practice, the social question was also fundamentally a psychic question and vice versa. While they never denied the reality of mental illness—like much of what would later be known as “antipsychiatry”—the doctors at Saint-Alban insisted on the importance of social conditions in the emergence and in the treatment of psychosis. Constantly evolving, adapting, and always revisable, institutional psychotherapy was meant as a “permanent revolution” of politics, society, and psychic life, all at once. Institutional psychotherapy fought to make possible a new form of self-knowledge by dismantling the regulatory system that governed the lives of the hospital community—not just the patients—and replacing them with others. Even the carceral environment of psychiatric hospitals or concentration camps could be transformed into a space of psychic healing and renewed communal bonds. For Tosquelles and his colleagues, all institutions (parties, unions, families, schools, etc.) could function similarly if they were treated with care. Indeed, the radical reorganization of the asylum (and of institutions more generally) sought to “disalienate” alienation but never once and for all. To produce a collective was to produce conditions of possibility, to work through the effects of transference, countertransference, resistance, and power, with constant vigilance—or, to recall Oury’s words, ne pas laisser en passer une (“to never let one go by”).