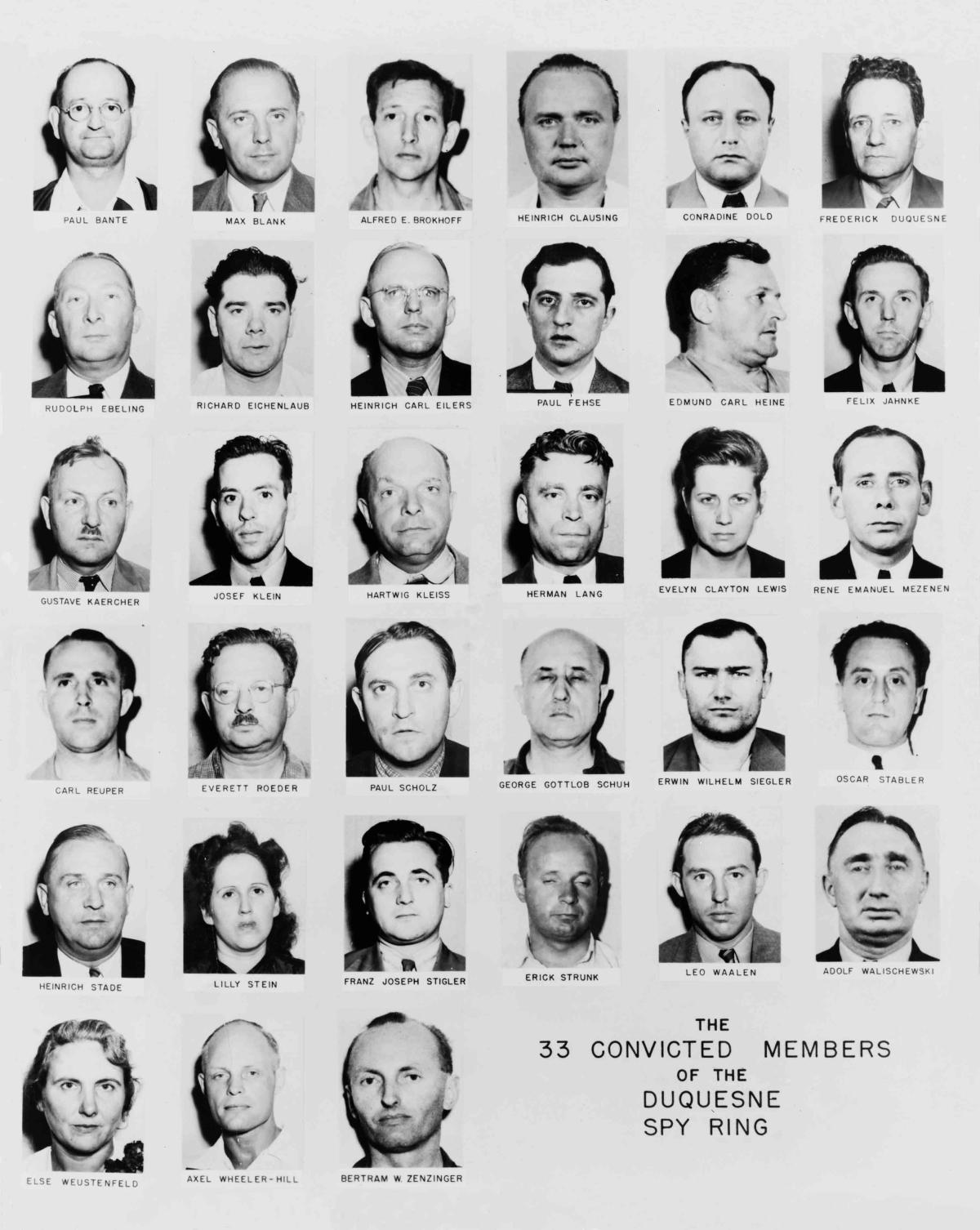

Five days after Pearl Harbor, an American citizen by the name of Edmund Carl Heine was convicted of spying for the Nazis. He had been arrested, along with 32 other members of a network of Nazi agents. The Duquesne Spy Ring—as it would come to be known—was the largest espionage case in U.S. history and would be counted among FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s major successes.

Yet three months after the atomic bombs fell on Japan and brought the war to a close, Heine successfully appealed his conviction. Yes, it was true, he had passed information about the U.S. aviation industry to the Germans. But all of it had been gathered from public sources; none of it had been secret. After spending the war in jail for violating the Espionage Act, the fifty-four-year-old former automobile executive was released. He had been guilty of spying until he wasn’t.

The little-known Heine case had fanned the fears of Axis spies and saboteurs in the weeks before America entered the war and helped encourage a new fixation on national security. Its details—and ultimate reversal—revealed how little a threat espionage actually posed to the American war effort.

Heine was born in eastern Germany in 1891, but his life was shaped by the global currents of the twentieth century. At the age of twenty-three, just weeks before the outbreak of World War I, he migrated to the United States, taking advantage of the last years of the open border to flee a forced marriage—he had impregnated a bar maid while traveling as a hardware salesman. Friends he made on the boat to America helped him find work in a hardware store in Detroit. After a brief interlude working on a farm, he took a job in the automobile industry and quickly rose the corporate ranks at Ford.

Six years later, Heine’s fortunate life hit an unexpected roadblock: Ford fired him. Exactly why he was fired never became clear, although the incident became the subject of dispute when Heine was charged with espionage six years later. Heine’s version of the story emphasized his patriotism and cast himself as a victim of Ford’s efforts to appease the Nazi government. He claimed that Ford wanted to place a German citizen at the head of its German operations and had ordered him to abandon his U.S. citizenship if he wanted to keep his job. He also asserted that the Nazis were boycotting any dealings with him because of a rumor that he had built American munitions during World War I. Ford executives disputed this account, suggesting that Heine was “not clicking with the German authorities” because of an illegal exchange of foreign currency with the manager of Ford in Holland and because he had become an unbearable and slightly slimy self-aggrandizer when placed in a position of authority. However it happened, Heine was out of work.

And amid the geopolitical turmoil of the 1930s, he could not reestablish his career. In 1935, he went to Spain to oversee the construction of an assembly plant for a Chrysler distributor. But upon the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he fled to Antwerp on a U.S. battle cruiser. A subsequent assignment to North Africa was undermined by political upheaval and the collapsing international market for cars. In 1938, Chrysler fired him. Heine, along with his wife and three children, retreated to a family home in Bavaria, where they lived on his considerable savings through the last days of the peace.

In late 1939, after the Nazi invasion of Poland triggered World War II, the U.S. consulate in Munich contacted Heine to inform him that he risked becoming stranded in Europe if he did not return to the United States to renew his passport. Heine began planning to cross the Atlantic once more. In March 1940, as he was making his arrangements, Heine met with Volkswagen executives, who asked him to do some work for them while he was in the United States. He was to recover some deposits paid to U.S. companies—the contracts had been broken amid the outbreak of hostilities—and gather information about the American aviation industry. Volkswagen, with its close connection to the Nazi war machine, wanted to know the types and quantities of planes that American companies were producing, the location and capacity of airplane factories, whether stainless steel or aluminum was the preferred material, how the planes were welded. They wanted, as Heine put it, a “fairly complete portrayal of the aeroplane situation in the U.S.”

And upon his arrival in the United States in the early summer of 1940, Heine set out to give them one. But he did so by entirely innocuous methods. He leafed through magazines, books, and newspapers. He read technical manuals and industry journals. For five dollars, he bought photographs of 50 planes from Thorell’s Aircraft Photo Service, which was run out of the Bridgeport, Connecticut, home of an aerial photographer in the Army. He went to the World’s Fair in New York to look at aircraft exhibits and chat with attendants. He placed an ad in Popular Aviation magazine asking for basic instruction about planes. On July 22, he wrote to the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, asking if the company would be so kind as to settle a bet he had with a friend after reading a recent boastful advertisement in a trade journal: Was the plane that Consolidated had built in only nine months, by chance, a B-24? A public-relations assistant at Consolidated promptly wrote back: yes, yes it was. Heine took all of this readily available information, curated and consolidated it, and wrote it up in reports that he signed “Heinrich.” And then he sent them to one of two addresses he had been given by Volkswagen. The first was in Lima, Peru. The second was on East 54th Street in New York. It was the address of Lilly Stein, a Vienna-born model who was working as a courier for a network of Nazi spies.

“Nazi spy ring” has an undeniably ominous tone. But, in general, Nazi intelligence efforts in the United States were comically inept, more Colonel Klink than supervillain. Establishing a robust network of spies within the United States was never a priority for the German regime. No one wanted to repeat the mistakes of World War I, when efforts to spy on the Americans had only antagonized them and brought them into the war. Combined with the usual tensions between competing branches of the Nazi state, support for spies remained ambivalent for much of the decade. As a result, Nazi operations were small-scale sideshows for most of the 1930s. By the end of the decade, when the war ramped up and caution could be abandoned, it was too late to cultivate agents with sufficiently deep cover. Nazi intelligence therefore relied on a haphazard crew of amateur agents, none of whom were really up to the task.

Take Guenther Rumrich, an alcoholic dishwasher who had twice joined the U.S. Army and twice gone AWOL—the second time after embezzling money. In 1936, Rumrich read a memoir by the chief of German intelligence during World War I. Inspired, he wrote a letter to a Nazi newspaper, lying about his military rank and offering his services to the Third Reich. If you want me, he said, put a personal ad in the New York Times for Theodore Koerner. Four days in a row in April, the ad ran, and Rumrich was in.

But Rumrich couldn’t do much. He read the newspapers and public reports on the U.S. military and sent his notes to an address in Dundee, Scotland. Pretending to be a major in the medical corps, he made a phone call to learn about the rates of venereal disease in the U.S. armed forces. He made some crude and quickly abandoned plans to lure the commanding officer of a coastal artillery unit to a hotel in Washington for a fictitious meeting, where an accomplice would jump out of a closet and steal his documents. Pretending to work for the State Department, he tried to order blank passports from the Passport Division: The Nazis wanted to run agents into the USSR disguised as Americans.

Rumrich was easily caught. The Passport Division quickly twigged that the strange passport order was a hoax and alerted the New York Alien Squad. Meanwhile, British intelligence was monitoring all mail going to that address in Dundee, which belonged to a Scottish-German hairdresser with a penchant for spy novels, whose “feeble” efforts at spy craft had been quickly identified. When MI5 read about Rumrich’s plans for the hotel smash and grab, it quietly alerted the United States.

After he was arrested, Rumrich snitched quickly, naming a series of equally underwhelming spies. For instance, Johanna Hofmann served as a courier taking documents across the Atlantic on German shipping lines. When FBI agents arrested Hofmann as her ship came into port in 1938, they found in her luggage both encoded letters and the key to the code. She had been supposed to learn the key by heart and then destroy it but had never gotten around to doing so.

The spy ring in which Heine was intertwined had similar flaws. The twenty-four-year-old Lilly Stein had migrated to New York with a passport provided by Nazi military intelligence and a visa provided by a lover in the State Department. As she was using her feminine charms to try to develop her own informants, she was also forwarding information sent to her by an odd assortment of self-selected spies. Axel Wheeler-Hill, a notorious Nazi sympathizer and brother of the leader of an American Nazi organization known as the German American Bund, volunteered to radio secret messages to Hamburg, only to realize he didn’t know how to set up the radio. He eventually had a friend build him one, but the friend—another flamboyant Nazi—went about it so conspicuously that the radio-parts salesman reported him to the FBI. The aging Fritz Duquesne, a self-aggrandizing soldier of fortune who had been writing his own legend since fighting the British in the Boer War (he had spied for Germany in World War I, escaped from multiple jails, advised Teddy Roosevelt on big-game hunting, claimed to have guided the U-boat that killed Lord Kitchener, and pretended to be an Australian war hero on the New York lecture circuit), helped out by gathering “intelligence” on U.S. gas masks from stories in the New York Times.

Because the Germans failed to compartmentalize their network, all of these spies were soon connected by one man at the center of the ring: William Sebold, a German-born American citizen who had been blackmailed into working for Nazi intelligence when visiting his mother in Mülheim in 1939. Just before the trip, Sebold had quit his job as a mechanic at the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, but the position was still listed on his immigration card, which drew the attention of the Gestapo. If he wouldn’t spy for the Nazis, Sebold was told, they would tell the Americans that he had failed to disclose a youthful smuggling conviction when he had migrated to the United States, a violation that would jeopardize his American citizenship.

It was a desperate tactic to recruit an intelligence agent, and it backfired. Sebold agreed to participate, was quickly trained in rudimentary spy craft, and returned to New York, where he established a dummy business corporation (“Diesel Research”) to coordinate U.S. efforts and communicate with Nazi officials via shortwave radio. But Sebold had been allowed to visit the U.S. consulate in Cologne before his departure and had promptly informed it about his dilemma, so from the jump he was working as a double agent. With help from the FBI, Sebold leased an office for his dummy corporation in room 627 in the Knickerbocker Building on Times Square. FBI agents in rooms 626 and 628 secretly filmed his clandestine meetings with Nazi spies. Meanwhile, the FBI oversaw all Sebold’s radio communications—they read incoming messages, edited outgoing messages, and added a stream of false intelligence to the mix for good measure.

By the middle of 1941, the FBI had what they needed. On June 27, 250 FBI agents swept out to arrest the 33 members of the ring. The largest espionage arrests in the nation’s history were a media sensation. Despite Duquesne’s marginal involvement, the elderly glory hound got the headlines. News of the Duquesne Spy Ring was on front pages across the country—part of a broader media panic about Nazi spies in a nation panicked by the turmoil of a second world war. Only if readers followed the jump and read to the end of article might they learn that an automobile executive named Edmund Heine was one of those arrested. The New York Times carried pictures of 27 members of the ring. The boringly bourgeois Heine, whose spying evoked little of the literary thriller, was not one of them. The reversal of his conviction four years later would get even less coverage.

America’s enemies actually conducted astonishingly little espionage during the war. After the dismantling of the Duquesne Spy Ring, the Nazis managed to land just two small teams of saboteurs on U.S. soil over the course of the war. Neither group accomplished any sabotage before disaffected members turned themselves in to the FBI. Once arrested, they were secretly tried in newly created presidential commissions that quickly returned guilty verdicts: Six of the accused were executed within eight weeks of their arrival in the United States. Setting a precedent that would matter a great deal after 9/11, the Supreme Court ruled that the entire improvised process was constitutional.

On the West Coast meanwhile, wholly imaginary fears of Japanese spies led to an even greater travesty: the expulsion of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast and their internment in harsh concentration camps in the nation’s interior. When it came time for the Supreme Court to consider whether this was constitutional, the War Department simply lied, making up hundreds of instances of subversive activities to justify internment as a “military necessity.” The court concluded that it had no reason to question the “judgement of the military commander that the danger of espionage and sabotage to our military resources was imminent.”

By 1945, Americans had proven themselves willing to twist their constitutional order out of shape to address a nonexistent threat of Axis espionage. And it would soon become clear that there had been spies operating in the U.S. during the war. They had been working not for the Axis but for an ally: the Soviet Union.

Adapted from the book State of Silence: The Espionage Act and the Rise of America’s Secrecy Regime by Sam Lebovic. Copyright © 2023 by Sam Lebovic. Reprinted by permission of Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books LLC., a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group Inc., New York, NY. All rights reserved.