Officer Clancy of the Chicago Police Department could barely believe his eyes: It was five in the morning and two nuns were scuttling around the perimeter of the abandoned North Shore Hotel, a shuttered six-story building along Lakeview Avenue. The nuns were up to something. They pulled a clothesline taut, bent down, and made quick marks on the sidewalk and in a small notepad. Puzzled, the officer flagged down his sergeant, who solved the mystery: The women were from an Italian group of nuns who planned to buy the property.

The nuns had been sent by Mother Frances Cabrini of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart. Cabrini suspected that the property owners were taking advantage of the sisters by building houses on the lot originally slated for a hospital—and she was proven correct.

The early morning episode has been described in a few recollections of Cabrini, the first American saint, including the novelistic biography Immigrant Saint: The Life of Mother Cabrini by Pietro Di Donato. Di Donato is best known for his 1939 novel, Christ in Concrete, a powerful depiction of the Italian immigrant laborer experience, based on a story that he’d published in Esquire while he was himself a twenty-five-year-old bricklayer. Di Donato’s visceral, funereal prose dramatized the death of his own father, a bricklayer from Vasto, Italy, who died in New York City on Good Friday, 1923, in a construction accident.

Losing his father soured Di Donato on the American dream and punctured his cradle Catholicism. Yet Cabrini’s exemplary life helped Di Donato make peace “with the essence of Christianity.” He was originally tasked with researching her life for a potential film, but when that project stalled, he developed his notes into a book. Di Donato’s religious skepticism was tempered by his recognition that Cabrini was a consequential figure: a woman fully Italian and fully American, a pragmatic and empathetic leader, and a remarkable humanitarian whose faith charged her tireless work for impoverished and marginalized immigrants.

The Catholic Church declares saints through an exhaustive process that begins at the local diocesan level. One must either live a virtuous life or be martyred. The diocesan bishop conducts interviews with those who witnessed the candidate’s life or martyrdom. Compelling cases are sent to Rome, where the candidate’s life is examined by the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints. Theologians forward candidates to bishops, cardinals, and, ultimately, the pope. Finally, the Church must typically attribute two miracles to the intercession of the candidate—often in the form of healing that resists explanation by a rigorous evaluation of medical experts.

Traditionally, the process begins no less than 50 years after the candidate’s death. Pope Pius XII waived this requirement for Mother Cabrini because of her especially virtuous life: “She gathered endangered youth in safe houses, and taught the holy and rightful principles. She consoled the spirit of the imprisoned, giving them the comfort of life eternal,” he said. “She consoled the sick and the infirm gathered in hospitals, and cared for them assiduously. Especially towards immigrants, who had left their own homes . . . did she extend a friendly hand, a sheltering refuge, relief and help.”

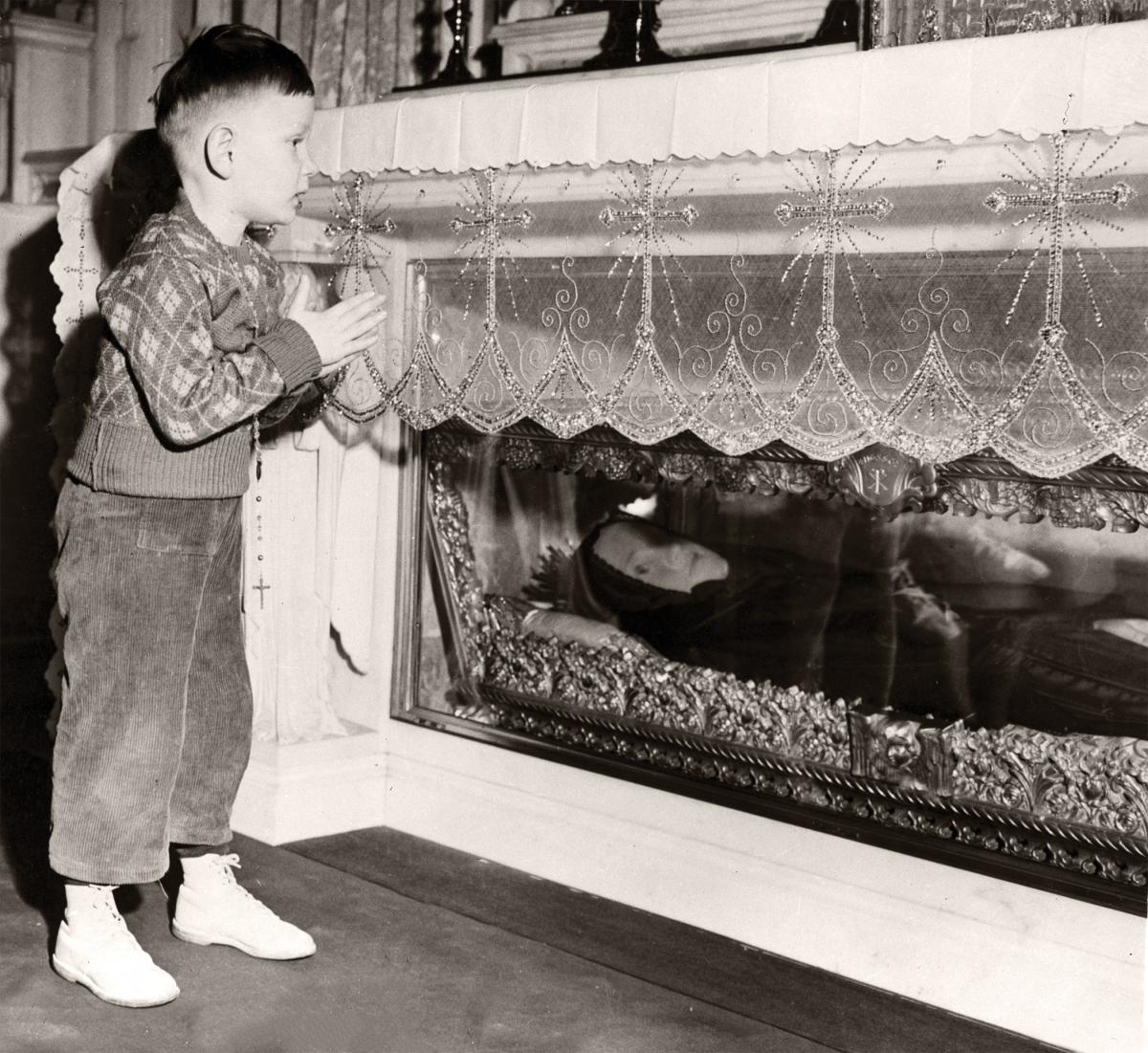

Cabrini was credited with miracles as well, including healing two Italian men whose chronic illness and burn injuries stymied physicians. Her posthumous miracles included the spontaneous healing of a nun and a child, through prayers requesting her intercession.

On July 7, 1946, as the scorching summer heat in Rome caused the candles in St. Peter’s to melt, Frances Xavier Cabrini was canonized a saint.

Mother Cabrini crossed the Atlantic Ocean 24 times. Her travels brought her to Colón, Panama; Puntarenas, Costa Rica; Mendoza, Argentina; Callao, Peru; Coquimbo, Chile; Barcelona, Spain; Liverpool, England; São Paulo, Brazil; Le Havre, France. She journeyed across the United States from New York City to Chicago, New Orleans, Denver, Butte, and Burbank.

Yet her life began humbly. She was born Maria Francesca Cabrini on July 15, 1850, in Sant’Angelo Lodigiano, Lombardy, Italy. She was baptized immediately, on the day she was born; most of her siblings would die before they reached their teenage years. She was confirmed several weeks later and made her first Holy Communion when she was nine. (At the time, Confirmation predated Communion in the Church). When interviewed in 1909, Fr. Melchisedecco Abrami, her childhood priest, recalled that the frail Cabrini “was so small in size that I used to call her ‘my tiny one.’”

Her slight stature complicated her desire to lead a religious life. She was not granted membership in the Daughters of the Sacred Heart because of her poor health. Years later, after she contracted smallpox while helping the sick, she was rejected by the Canossian Sisters of Crema due to the influence of a priest, who valued her abilities as a teacher and found her too difficult to replace.

Ultimately, Cabrini was recruited to save the House of Providence, a mismanaged diocesan orphanage for girls in Codogno in Lombardy. She made her profession of vows in 1877, taking on the name Saverio—Italian for St. Francis Xavier, one of the founding Jesuits. The religious community in Codogno remained tenuous, and the bishop asked Cabrini to start a new order. The Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus was established on November 14, 1880, and its international mission would become her life’s work.

Cabrini originally wished to travel to China, but Pope Leo XIII responded: “Not to the East, but to the West.” He had recently penned Quam Aerumnosa (also known as “On Italian Immigrants”), an encyclical released on December 10, 1888, directed to American archbishops and bishops and pledging to send those of the Italian religious order to the United States to provide spiritual and material support. In it he struck an elegiac tone:

How sad and fraught with trouble is the state of those who yearly emigrate in bodies to America for the means of living is so well known to you that there is no need of us to speak of it at length. . . . It is, indeed, piteous that so many unhappy sons of Italy, driven by want to seek another land, should encounter ills greater than those from which they would fly. And it often happens that to the toils of every kind by which their physical life is wasted, is added the far more wretched ruin of their souls.

Cabrini and several fellow sisters left Italy on March 23, 1889, and arrived in New York City on March 31. The sisters were surprised to learn that there was nowhere for them to sleep—there was no convent in the area. Instead, they spent their first night in a filthy rooming house, and, due to bedbugs, took turns sitting on a chair rather than sleeping on the bug-infested mattresses.

According to biographer Theodore Maynard, Fr. Morelli warned Cabrini and her fellow sisters that even American clergy “share the general prejudice against us,” and noted that Italians had to “hear Mass in a basement apart from everybody else.” Few Italian priests were available to celebrate Mass in the city, let alone hear confession. As Pope Leo XIII described, the absence of regular worship and a parish community had immediate consequences—“very few are consoled by a priest in death, and many are deprived of baptism at birth”—and created a lineage of Italian Americans whose children would lead the same spiritually unmoored lives.

Cabrini embraced the spiritual and practical challenges of her mission. “Our mode of work is to go right down into the Italian quarters and go from house to house, from apartment to apartment,” she told a reporter. The sisters, another news report observed, ventured into “certain forbidding places where not even the police dare to enter.”

“We are recognized,” Cabrini noted, “by all Italians and many of them are glad to see us.” Many, but not all. In addition to the anti-Italian sentiment among other Catholics in America, Cabrini recognized that southern Italians carried their suspicion of religious institutions across the Atlantic—not to mention that she, like some of her other sisters, was blonde and blue-eyed: clearly of northern Italian stock.

Yet she was deeply devoted to even these skeptical immigrants and knew much of their hesitancy arose from reasonable worries. Cabrini, though, was no ordinary missionary: She had a preternatural drive to work wonders. It began with her ambition to help immigrant children, to ensure “they have proper homes and schooling. Our object is to rescue the Italian orphans of the city from the misery and dangers that threaten them and to make good men and women of them.”

Those lofty goals were anchored in the pious structure of her days, which typically began with her waking at 4 a.m. for an additional hour of prayer before the Order of the Day, which started at 5 a.m. She was known for entering into a trancelike state during the Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, the solemn, extended prayer and adoration in front of the Holy Eucharist. Then she ate a small breakfast and read newspapers before going through mail, including letters from fellow sisters. Other than the communal examination of conscience halfway through the day, she spent most of her hours focused on missionary work. Around 6 p.m., she had supper, followed by evening recreation and spiritual reading.

She practiced small rites of asceticism; Mother Saverio DeMaria, a Missionary Sister who acted as Cabrini’s “secretary and as a novice,” noticed that Cabrini “always took the same number of grapes from a cluster.” Cabrini encouraged others to lead as she did, to inspire through shared sacrifice, and to deliver honest criticism, grounded in love. “Tell them the facts first to convince them of their faults, and then encourage them,” she said. “Don't ever leave them without a kind word to make them understand that you love them and that you desire only to help them.”

Cabrini encountered a number of doubters who didn’t believe her mission was necessary or even that a woman could so lead. Early into her initial visit to America, an archbishop told her she would be wise to return to Italy. Her biographer Mary Louise Sullivan noted that a Roman prelate, or high-ranking member of the clergy, once told Cabrini that missionaries were typically men. Cabrini responded, “If the mission of announcing the Lord’s resurrection to his apostles had been entrusted to Mary Magdalene, it would seem a very good thing to confide to other women an evangelizing mission.” Sullivan, who served as president of Cabrini University in Pennsylvania from 1972 to 1982, succinctly described Mother Cabrini’s mission: “to preserve the Roman Catholic Christianity of Italian immigrants, to strengthen their cultural identity and to facilitate their assimilation into American society.”

In Sullivan’s view, Cabrini “would be at home with some contemporary historical, sociological and religious approaches which emphasize a more gradual assimilation of immigrants than did the rapid Americanization theories of her day.” Cabrini’s prescient view of immigrants was not mere intellectual theory; she accompanied her fellow sisters on the streets and into homes. She held hands in prayer and comforted sore shoulders.

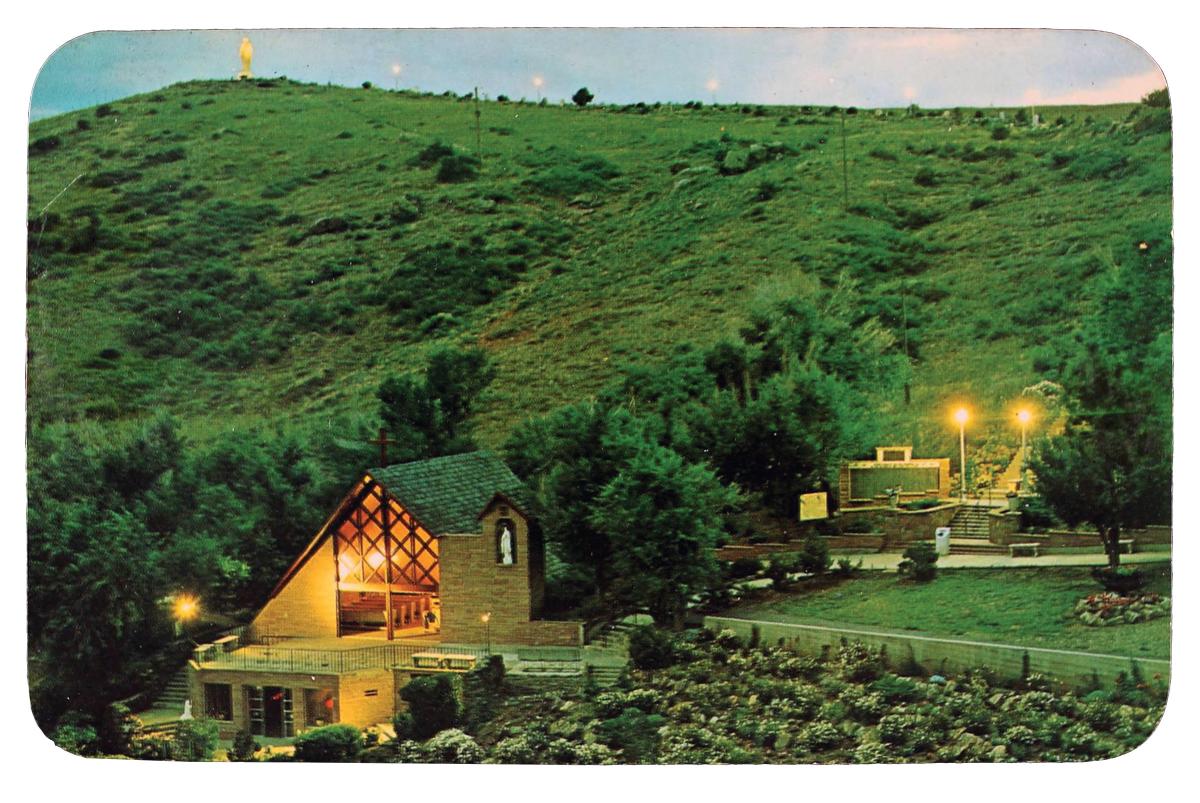

Her time in Denver steeled her resolve and solidified her approach. Cabrini arrived in 1902 and was informed by Bishop Nicholas Chrysostom Matz that many immigrant Catholics “have not received the sacraments for many years. They are exhausted from their labors and live far from a Church, where Holy Mass is rarely celebrated.” The sisters met the poor where they were, influencing Catholic leaders to follow their example: “Other times,” Cabrini wrote, “the bishop himself, in this immense temple formed by nature, with a tree trunk for his episcopal stool and the damp mountain moss for a carpet, or in the green meadow still wet with dew, administers Confirmation to his children on whom God smiles from heaven.”

Cabrini opened a school in the city, enrolling 200 children on the first day. A structured education was a godsend for the immigrant children, but Cabrini was savvy enough to recognize that the ceremonial and spiritual overtones of the school’s opening served another, equally important, function. “It was a new sight for the Italians of this city,” she recalled in a letter to her Missionary Sisters. “We saw genuine joy shine in them all. . . . The modest smiles of the parents concealed their pride in seeing their children enter in good order to take their places as a march was played.”

These were sons and daughters of laborers, and their bone- and soul-crushing work moved Cabrini. Some of the most poetic moments of her correspondence—13 volumes of which are housed at Cabrini University—are when she writes of their travail, with a sympathy for workers that likely inspired writers like Di Donato and others who saw their own parents and families suffer. “In these very deep caves far from the light of the sun,” she says, “so many thousands of miners spend their lives absorbed in intense labor, sometimes standing in boiling water coming from the mineral springs that are plentiful here. While the companies amass millions, most of the workers labor under severe hardships, furiously chipping away with pickaxes, searching for the vein that will mean their fortune and that of their children. Most often, after years and years of hard labor, their only recompense is a slim gain.”

Cabrini would return to these sentiments in other letters, observing that these economic disparities transcended any one region. While traveling by train, she observed “these poor dear countrymen laboring on construction of railroads in the most perilous, narrow passes through the mountains, miles away from any habitation, for years separated from their families and their Church.” These “poor immigrants” were deceived by “protectors” who hid “their actions under the guise of charity and patriotism.” Italian laborers were often given “the most difficult jobs,” and were regarded by their employers as merely “a clever machine assigned to complete a set task.”

Exhausted from work, the Denver miners had little time or energy for religious observation and spiritual sustenance. They entered the mines at six in the morning, remaining in that darkness until noon. After a half-hour lunch, they returned to the mines, staying until five in the afternoon. They then washed up, ate supper, and collapsed into sleep. The harsh structure of their days was the inverse of the regimented but generative, daily schedule of Cabrini’s religious order.

Once again, the sisters went to the workers, this time underground: “They have descended to a depth of 900 feet, lowered into the mine in a bucket barely big enough to hold them, through an opening no larger than one square meter cut obliquely in the rock. Compressed air introduced in the cave made breathing possible. Other times, they walked at the same depth for several kilometers through narrow tunnels to bring a good word to those poor men and remind them of the eternal truths.”

These men, Cabrini sadly noted, already knew of hell from their time spent in those “dark pits, where breathing is laborious and the only light is from a few tallow candles, giving a limited idea, yet very expressive one, of the reality of eternal darkness.”

The sisters were able to awaken the latent Catholicism in these men—likely owing much to their shared heritage. As Cabrini noted, these Catholics had fallen away from the Church for a variety of reasons: physical and spiritual exhaustion, poverty, and geographic isolation. Yet their return to faith seemed to illuminate their spirits. “How moving it is to see mature men cry tenderly at finding themselves again in an Italian church, where the word of God reaches them in their mother tongue, and where all reminds them of the fatherland abandoned so long ago,” Cabrini wrote. “They recall the dear memories of childhood, the bell tower of their native town, the church square, the feasts of their patron saints and the solemn processions.”

Although deeply Italian in her language, affect, and culture, Cabrini was enamored with the United States—as a concept, and as an expansive, beautiful space. Her correspondence is rife with inspired descriptions of the land: “I can say that there is neither hill nor valley that I have not visited, with an ever-growing admiration for the goodness of the Lord so amply demonstrated in this blessed country.”

She writes of Colorado Springs: “Scattered about are myriads of brightly colored rocks, sculptured by nature into the most unusual shapes. Some are imposing, some grotesque, others austere. Some others are nonsensical and challenge the imagination.” Traveling elsewhere through the state, she marveled how the name Colorado “indicates its multicolored mountains, cobalt sky, birds and flowers of unlimited varieties and brilliant colors.” She added that “there is much to admire and for which to thank God, who has let fall on earth rays of His infinite beauty and power.”

Awed by the sight from her glass-bottomed boat on a trip near Santa Catalina Island in California, Cabrini describes the underwater “mountains with plains and valleys, green with marine algae that in some places reached a height of one hundred feet, swaying with the movement of the water. In their midst I saw an almost infinite variety of aquatic plants, some of which had flowers of beautiful violet plumes, and diverse fruits of delicate, fresh colors, like shoots just budding in the spring. All were swaying with the water, as though a cool breeze was moving them.” In Cabrini’s words, we find an affirmation of America—truly a beautiful land that compelled immigrants.

At the same time Cabrini was traveling throughout the United States, building relationships, and sharing experiences with immigrants, she remained in contact with her fellow Missionary Sisters in Italy and elsewhere. “The distance between us does not matter,” she wrote in one letter, “we are always near each other, always enclosed within the small space of this very small world, which sometimes seems so huge to us, to our small and limited minds. . . . So another four thousand miles more is really very little after all.” Cabrini recognized the social limitations that she and her fellow missionaries experienced as immigrant women themselves—yet never failed to find an inspiring path forward. “What we as women cannot do on a large scale to help solve grave social ills is being done in our small sphere of influence in every state and city where we have opened houses,” she wrote. “In them we shelter and care for orphans, the sick and the poor.”

Change that sometimes appeared humble in scope and scale to younger sisters was, in Cabrini’s view, foundational and essential. Once she made the difficult decision of turning away a self-congratulatory candidate for holy orders. The decision troubled Cabrini, but she concluded, “I need many subjects but I wish to have only those who are humble, detached from themselves and from their talents, for I am positive that a humble subject can work for fifty or more. Without humility, peace is lacking and grace departs.”

In 1905, a New Orleans newspaper included a prophetic paragraph: “Mother Cabrini is one of the remarkable women of this century. One hardly knows how to begin to describe her, but there is an intangible something about her which suggests the Catholic saint. It is the lives of just such women that are immortalized by canonization.”

Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini was a pragmatic leader who knew that spiritual and material worlds are intertwined.

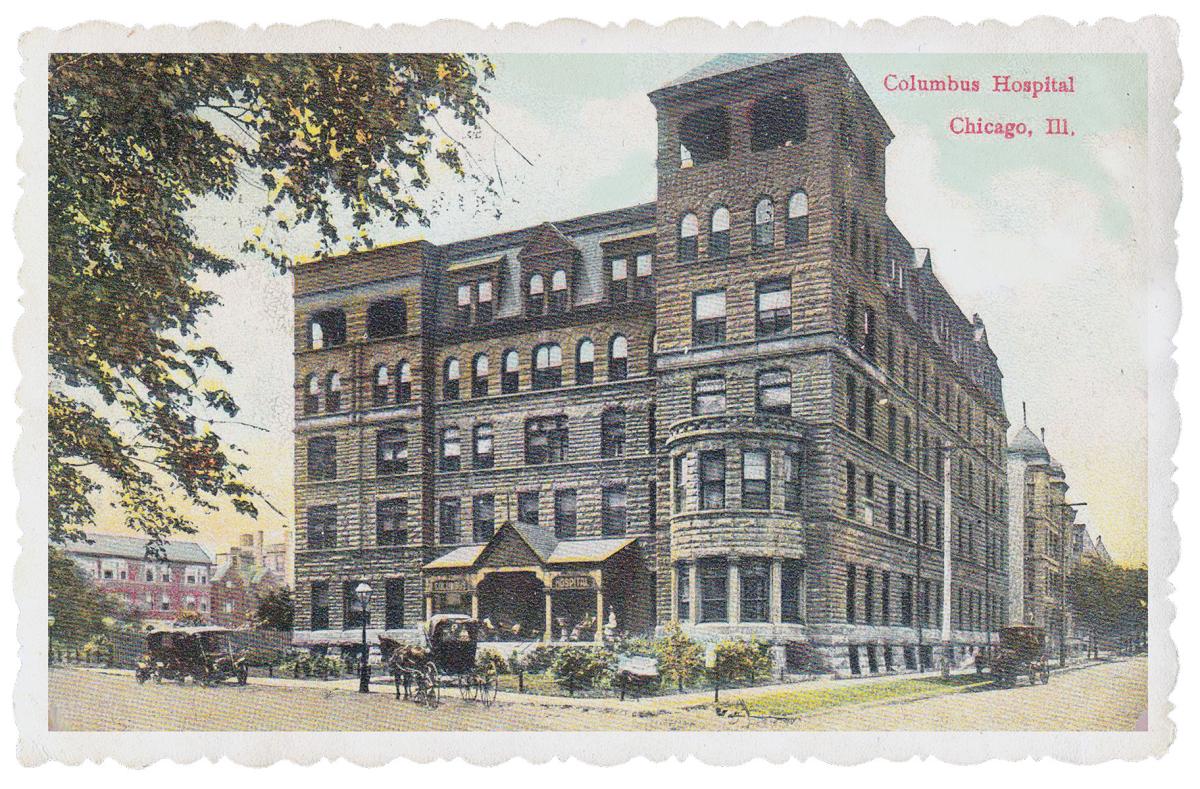

As Cabrini reflected in a letter, “There was no lack of persons coming to tell me, ‘Mother, we won’t succeed. There is too much to be done and the difficulties are too numerous.’” Cabrini was doubted; she was maligned. She had faith, though, and drive. The Columbus Hospital opened in 1905. At the opening ceremony, the featured speaker pointed to Mother Cabrini in the crowd, saying, “And to whom do we owe this great work? To a little woman!”