The biography of Columba Stewart displayed on the home page of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library describes his extensive travels through the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and India in his efforts to help Christian and Muslim communities preserve and digitize their precious medieval and modern manuscripts.

It mentions his rescue work in Timbuktu and his delicate and often dangerous efforts in war-torn Iraq to help Christian churches there save almost two millennia of religious thought from destruction. It goes on to describe his academic credentials: degrees from Harvard, Yale, and Oxford, fellowships from ‘all the right foundations,’ the grants that he has obtained for the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, and his distinguished publications on early Christian monasticism.

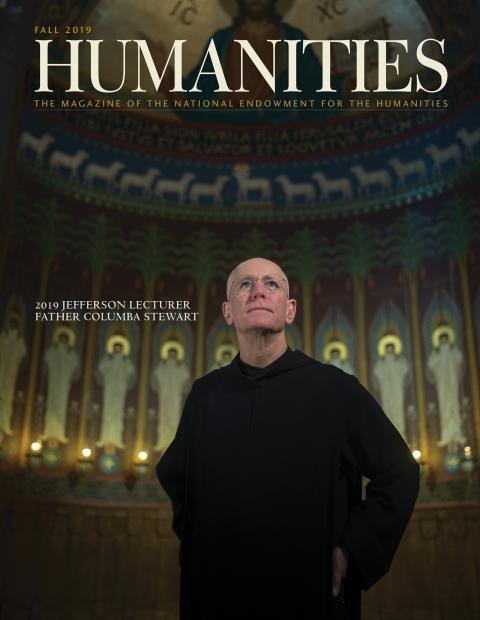

But what the biography does not mention, the photo of Columba makes abundantly clear: There he stands, arms folded, dressed in the habit of a Benedictine monk. This monastic identity is the most salient feature of what makes Columba Stewart the man he is, what drives him in his scholarship to understand the earliest history and even the prehistory of monasticism, what gives him the courage to enter combat zones to rescue manuscripts that few people care about and that still fewer can read. Columba Stewart is a monk.

A distinguished historian of late antiquity once wrote that “the history of faith is far too important to be left to adherents alone.” In an age of postreligious secular scholarship, when most of the finest interpreters of the Christian tradition are at best agnostic, approaching their sources with the same detachment one might bring to the study of the cult of Zeus, here stands a monk who over three decades ago prostrated himself before the altar and solemnly vowed “stability in this community, conversion through a monastic way of life, and obedience according to the Rule of our Holy Father Benedict.” How then should we understand Columba Stewart, not just as a scholar, peripatetic adventurer, and able fund-raiser, but as one who believes deeply and who lives by a rule written nearly fifteen hundred years ago?

Columba is certainly not one to shy away from his religious identity and commitment: “I write as a monk about a monk” is the opening sentence of his widely praised biography of Cassian. But, of course, as he says in the next sentence, “it is not that simple.” Nor, indeed, is Columba himself. We met in connection with his work to help digitize and preserve manuscripts. I found him extraordinarily empathetic and collaborative. Later, he spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study, where I was a professor.

I think that I can understand something of his Catholicism because, like him, I was nurtured in the Catholic milieu that is the Gulf Coast: a thin band of European-style Catholicism stretching from Houston and Galveston in the west to Pensacola in the east, at times reaching just a few miles into the interior, but in Louisiana much farther beyond New Orleans to Baton Rouge and Acadia country. This is emphatically not the Catholicism of the mass migration of the nineteenth century, of poor laborers and peasants fleeing poverty and finding themselves in a hostile nativist and Protestant America. On the Gulf Coast, Catholicism was the norm, and the immigrants were the Protestant Americans. Being Catholic was a natural part of life, and if one of Columba’s Catholic classmates at Harvard once told him that “he wore his Catholicism like a cashmere sweater,” she spoke more accurately than she knew. Our Catholicism was never stiff and starchy, protecting our bodies like armor against a hostile world. It was soft, infinitely pliable, clinging to the contours of our bodies, but for that more intimate than any ethnic Catholicism could hope to be. It is simply who and what we are. Cashmere doesn’t constrict: It is both sensuous and provides for fluidity of motion. Hence when, in the course of his university studies, he began to love the textual traces of early Christian monasticism, his Catholic faith let him move freely toward an embrace of this tradition with his whole being, but without losing perspective on himself and his world. His cashmere Catholicism continues to serve him well.

From his early engagement with the foundational texts of monasticism, Athanasius’s Life of Antony, John Cassian’s Institutes and Conferences, and the writings of Evagrius Ponticus, Columba has sought and found a deep resonance between the psychological insights of these antique men and his own sense of himself. Antony’s struggle with his inner and outer demons resonated with Columba’s experiences of obsession, temptation, and despair. The way that Cassian drew the most intimate and private realms of bodily and sexual experience into the project of transformation through grace gives Columba hope that we go to God as whole persons, body and soul, never one without the other. Evagrius, the most philosophical of the three, moved Columba with his astonishingly apt psychological analyses, even while he saw that Evagrius’s rigidity and dependence on Hellenistic schemes of thought cannot be part of our present world.

Indeed, much of what these and other early monastic writers produced Columba finds not only alien but even abhorrent. A person of the twenty-first century, he has no desire to be a monk of the fourth century or any other century than his own. His faith is not a shield against the contemporary world, and his monastic vocation is not born of a desire to escape into some idealized past. His keen appreciation of the vast differences in psychology, society, and spirituality between himself and these early monastic figures, however attractive aspects of their lives and writings might be, gives him the independence to approach these foundational figures with the critical detachment and exacting philological tools of contemporary scholarship. This critical approach to his sources has helped him deconstruct the received traditions of Egyptian monasticism and its influence to recognize, in the fragmentary evidence gathered primarily from Syriac texts, layers of early monasticism, quasi monasticism, and premonasticism as they developed in the towns and countryside of the eastern Mediterranean before the age of Antony. Thus, in recent years, his scholarship has turned increasingly toward those forms of communal religious life that were written out of the master narrative of Christian monasticism, to discover how women and men answered the call to Christian perfection in ways that hardly resemble anything that might be called monastic. Without, in the least, calling into question his own faith or his commitment to the Benedictine tradition, he is in the process of undermining the master narrative that for centuries dominated our understanding of how that tradition came into being.

At the same time, the responsibilities assigned him by his abbot to lead the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library have taken him far from the life in community prescribed by the Rule of Benedict. Like the great Benedictine medievalist of the last century Jean Leclercq, he might be easily classified with those gyrovagues, wandering monks roundly condemned by generations of monastic writers. But Columba does not wander: He travels with a purpose and with a mission, much as did Cassian. True, Columba is often far from his brethren at Saint John’s, and his duties often make the rigid observance of the monastic hours impossible. But, as Columba observed in writing about Cassian,

The essence of the monastic life lies in the intention and orientation with which it is lived rather than its structures and disciplines. Spending years outside of purely monastic environments and writing for monks who might find themselves called to service beyond the monastery, Cassian asserts that the core of the monastic vocation is the monk’s belief in heaven. Such eschatological faith brings the freedom of engagement on which monastic life for the world must be based. Such faith enabled monks like Cassian to do whatever they were called on to do, monastic and pastoral, as if it mattered absolutely, while knowing that from another perspective it mattered not at all.

Commanded by his abbot, inspired by his deep love of the monastic tradition and his passion for engaged scholarship, Columba travels the world to preserve the full heritage of human thought, Christian and Muslim alike. In his research, teaching, and writing, he expands our understanding of the origins of the life he has embraced and the difference between that world and ours. He does all this as if it mattered absolutely, while knowing, as a monk and a Christian, that from another perspective it matters not at all.