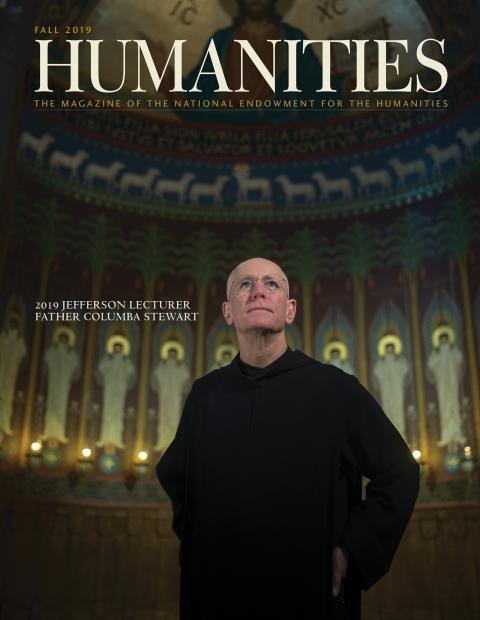

On October 7, 2019, Father Columba Stewart, a Benedictine monk, will follow in the footsteps of Lionel Trilling, Walker Percy, Toni Morrison, and more than two score other distinguished humanists to deliver the 2019 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, the highest award of its kind bestowed by the federal government.

Fr. Columba is executive director of the NEH-supported Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML) at Saint John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota. Since the 1960s, HMML has been photographing sacred manuscripts from Europe to northern Africa to the Middle East and India in an effort to preserve and make digitally available endangered texts of multiple religious traditions. As Atlantic magazine put it, Fr. Columba is the “monk who saves manuscripts from ISIS.” He is also a scholar of Early Christianity, the author of three academic books, and an NEH research fellow twice over.

In a quiet library inside the Saint John’s Abbey Guesthouse, NEH Chairman Jon Parrish Peede sat with Fr. Columba and asked him about his life as a monk, his beliefs, favorite books, and the mission of cultural preservation.

JON PARRISH PEEDE: When did you first feel the call of God in your life?

FR. COLUMBA: I grew up in a home that was at least notionally Catholic, but there was always a strong sense of Catholic identity, particularly for my mother, a sense of history, of art, literature, music, and of different spiritual paths. We felt like we were part of something ancient and significant, and that continues to be one of the main attractions of this particular religious tradition to me.

PEEDE: What books or authors have been of value to you in your life? What kind of reading gives you pleasure and insight?

FR. COLUMBA: I’m a fourth-century guy in a lot of what I do, but I’m kind of a nineteenth-century guy in terms of the literary culture that I identify with. It was an age of incredible change and innovation and social challenge but also an age which had sufficient continuity with the cultural past. I think it’s still difficult to surpass in many cases the prose of the nineteenth century in English or in French.

I am also a Southerner and have been influenced by Southern literature, Flannery O’Connor particularly, but not only. As a Texan with Louisiana roots, I’m well aware of how complex that part of our country is and of the efforts, particularly by novelists, to come to grips with that complexity. I also read widely in history and am very interested in the twentieth century. And, in all honesty, I read spy novels and other sorts of airplane reading.

PEEDE: What about Augustine’s Confessions or Merton’s work about the natural world?

FR. COLUMBA: Augustine is a complex figure, and The Confessions are a great example of the way that we can read an ancient text as a twenty-first-century person and think we’re reading about a twenty-first-century person because he’s so psychological, but that can be very deceptive.

Their understanding of what it meant to write what reads to many people as a memoir was not what we think of as a memoir. I find it interesting to try to get a handle on the similarities and differences and to be a wiser interpreter and incorporator of some of that in my life. A lot of earlier Christian literature is unsettling to a modern reader. It often is intolerant religiously. It doesn’t often embrace the fuller understanding of human diversity as we see it today, and yet they were on to something.

PEEDE: You went to Harvard, Yale, and Oxford, all secular institutions. How did those experiences interact with your life of faith?

FR. COLUMBA: I had a sense even when I was young that I wanted to have different sorts of experiences, and so I went to the East Coast for college, to an Ivy League school. I also wanted to be somewhere that felt older than Houston.

At Harvard, there was an active Catholic campus ministry and an active ecumenical ministry. At Memorial Church, Peter Gomes was the minister. A man of great erudition and inclusiveness, he became one of my mentors.

I don’t want to give the wrong impression. In college, I was doing all of the things people do in college, but I was often going to Mass and was active in that Catholic community.

I became very interested, as I continued my concentration at Harvard in history and literature, in the modern Catholic Revival in the Church of England. This would be Cardinal Newman and the Oxford Movement, particularly the rebirth of the avowed religious life in the Anglican Church.

I was myself a Roman Catholic, but I was fascinated by the phenomenon of the religious life and in the particular group I ended up writing about, the Society of St. John the Evangelist, a monastic witness in the Church of England of the nineteenth century.

When it came time to write my senior thesis, I wrote on the history of their founder. They had a monastery in Cambridge, right on the Charles River. So, they were my first monks, oddly enough. In that Episcopalian-Anglican tradition monastery, I first prayed the Divine Office, got a sense of the daily schedule of the life, and I really liked it.

From Harvard I went to Yale to start a PhD program in church history, which was going to be nineteenth century and then quickly became early Christianity, as my interests moved farther and farther back.

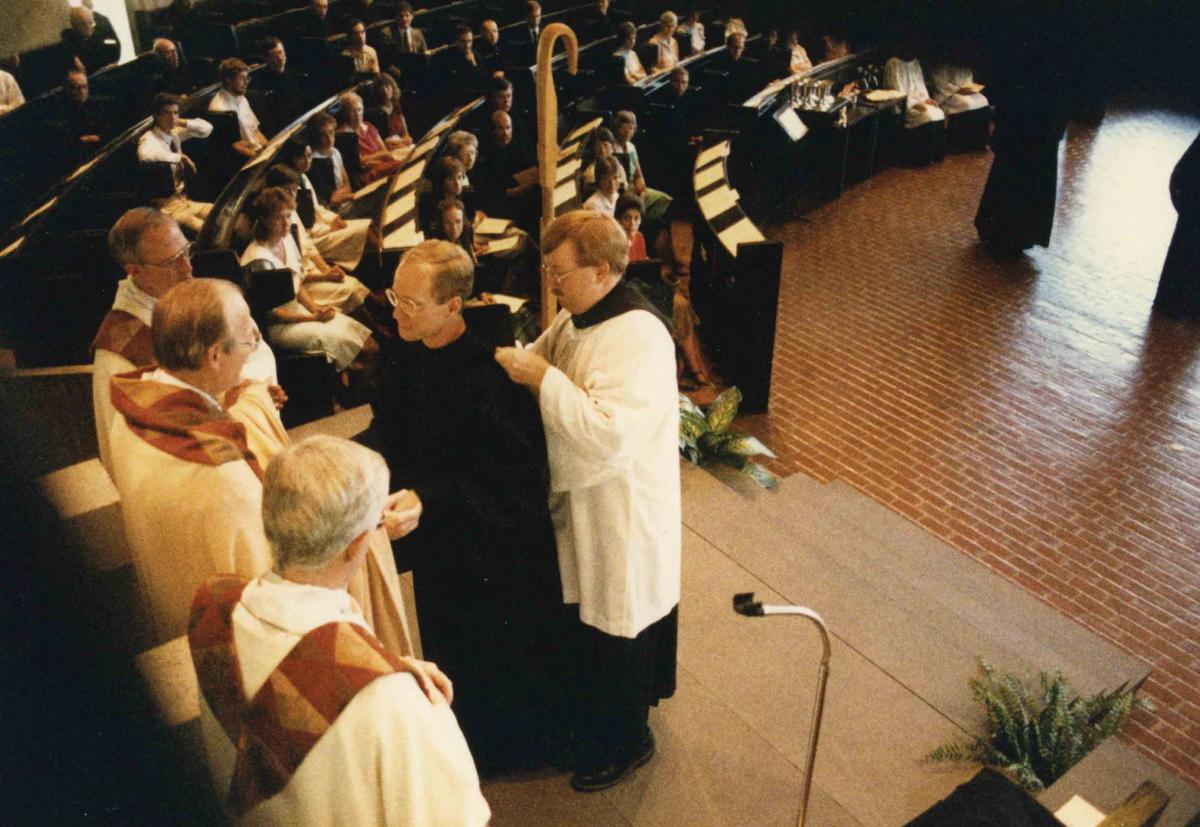

I had to learn German for the sake of the PhD requirements. I had met a couple of monks from Saint John’s, this monastery, and I was invited to spend the summer at the abbey in 1980 to work on my German. It was an amazing time.

It was the fifteen-hundred-year anniversary of the birth of St. Benedict. There was a symposium. There were VIP monastic representatives, men and women from around the world, all here in Collegeville, Minnesota, and, for someone like me interested in history, interested in the relevance of historical traditions in the modern world, it was a fantastic introduction to the possibilities of this way of life. Within a semester, I was in the monastery.

PEEDE: And how many years has it been since you took vows?

FR. COLUMBA: I entered the novitiate in 1981, made my first monastic profession in 1982, my final monastic profession in 1985, and then I was ordained to the priesthood in 1990. So, it’s been a few years.

PEEDE: An important part of that process is the name you take to be known by. Tell us about Columba.

FR. COLUMBA: Monastic life has a tradition of conferring a new name on the person who enters the novitiate. Since the Second Vatican Council, this practice has been optional in communities like mine, but there’s still a utility to it. At the time I joined, I was Andrew, but we already had a Father Andrew, a Brother Andrew, and a Brother Andre, and I did not want to spend the rest of my life being Andrew Stewart as opposed to one of the others. Also, I liked the idea of finding a saint’s name or a monk saint’s name that had resonance.

My first couple of choices, which I won’t reveal here, were already taken. Then I discovered St. Columba, and I confess I knew virtually nothing about him, but I learned two things about him, which ultimately came to have great interest to me.

One, he’s famous as being the first person to have seen the Loch Ness Monster. Now, I like lakes, bodies of water. I like to swim. That tradition is really a mere curiosity, but it was interesting to me since he had that encounter with the Loch Ness Monster in a part of Scotland that I have some family roots in.

The second and more significant point is he was famous for his love for books and his interest in copying books and spreading manuscripts. It was really the work of Columba, first in Ireland, then in Scotland, then of his successors in northern England and on the continent of Europe, that brought an incredible tradition of Latin learning back to the continent by that curious Celtic byway of the Irish monastic tradition.

And so that’s the element of Columba, the kind of book hunter, book collector, and person interested in the value and importance of the written word that I’ve grown into.

PEEDE: Do you believe there’s something deeper than luck or coincidence going on here?

FR. COLUMBA: I’ll be quick to say I believe in some kind of guiding providence, not in a way that excludes decisions we make, but when I look back, I ask myself, Why did a kid in Texas decide he wanted to study French in high school instead of Spanish? It made no sense at all, and now a big part of my work is in French West Africa. So I’m having to use the language that I studied in the work that I do, and that’s just one small example of the way many strands of my life got woven together.

PEEDE: What did you think monastic life might be like versus what it was and is?

FR. COLUMBA: I think part of what attracted me to monastic life was, for lack of a better term, the esprit de corps. Here’s a group of people, they’ve chosen to form a community. They have things they do together. We dress alike, at least for the formal occasions, such as when we’re in church. We profess the same vows, but there’s an amazing amount of room for individual difference.

Benedictines are different from some religious orders in that there’s not a particular work that we were founded to do. So, in our community, we have people who work in the garden, people who are good with their hands in the woodworking shop. We have PhDs. We have musicians. We have lawyers. You can really do just about anything with the talents that God has given you, but you do them to further the particular mission of the community and the place in which the community is founded.

So I knew there would always be room for me to grow and develop. Even in that first experience of looking around the monastery, I could see there was plenty of variety here, enough for me to believe that I could slot into this.

As one of our abbots once said, at the end of the day we’re all volunteers here. We make vows. We make a commitment, but just as people in any serious relationship or marriage have to do, every day you have to decide you’re still in this.

PEEDE: For those people who have no attraction to living as a monk but also feel adrift in the modern world, what elements might they take away from monastic life?

FR. COLUMBA: To my surprise, more and more people seem to be interested in incorporating some element of Benedictine or monastic practice in their lives.

There is the simple idea that you pray at certain points in the day. And there is the idea that you try to find like-minded people to form a community of support. To some people this is very attractive. They may even create formal quasi-monastic groups to provide this kind of support, even as they have children and do various other things.

There is a keen interest in creating structures to help people develop a life that feels like it matters and for it to be sustainable. Communities are threatened, and all of civilization may collapse. It’s collapsed before. We’re still around, and I think one of the reasons we’re still around is because we’ve learned over these centuries of the Benedictine life how to build a sustainable community that can incorporate new members.

The conditions around it may change, it may have to adapt, but these fundamentals remain: You live together, you pray together, you eat together, you work together, you have the shared reflection on biblical text, which is the essence of the way that we pray, and you take life seriously but not overly so. That has legs, and we’re seeing a really keen interest in how elements of that can be brought into other ways of life.

PEEDE: You have at least four or five touchstones here in Collegeville. You have the abbey. You have a world-class library and museum. You have this school, Saint John’s, a leading educational institution nationwide and particularly among Catholic undergraduate programs, and the graduate school of theology. Then you have 2,700 acres or so of lush land and a beautiful lake. Would it be a different experience if one of them were not present in your life?

FR. COLUMBA: If one of those weren’t here, it wouldn’t be the community that I joined. When someone is looking at the possibility of monastic life, we typically advise them to shop around a bit.

You need to find a place that fits, and, certainly for me, the natural environment was very important. I have a pretty strong element of mysticism in my makeup, and I have a way of understanding that within my Christian, my Catholic, faith, but the presence of the lake, particularly, and the woods that surround it, the way that we care for our land and try to steward it as best as possible, both for the enjoyment of people now and for the sake of future conservation, is pretty central to who we are and something that I value highly.

Obviously, the life of the mind is important to me. I’ve had the chance to teach. I’ve written books and articles. I’m an active lecturer. But this community and the daily routine of our monastic prayer, all of that grounds me and keeps me sane, and enables me to do the very challenging work that I do as director of HMML. I’m also fortunate to live in a community that believes in beauty and the importance of the visual environment. Every day I pray in a masterpiece of modern architecture, Marcel Breuer’s Abbey and University Church, and go off to work in another Breuer building, the magnificent Alcuin Library.

PEEDE: Returning to your education, how did you end up at Oxford?

FR. COLUMBA: I began a doctoral program at Yale. I had moved from college to graduate school with a sense that I was interested in the academic life, but I wouldn’t say it was a burning passion at that stage, and, in fact, I learned that I needed to look at some life issues first.

But after my four years of what we call monastic formation, it was time to talk about school again and, by that point, I was very interested in the origins of the monastic tradition.

This led me into using the Greek I learned at Yale and then learning Syriac so that I could look at these earliest layers of Christian asceticism, which created the kind of substrate for the development of monasticism.

Oxford was the place to go because of the people who were teaching there. I also liked the idea of a system that let you go off and do research and write, and it proved to be a very good environment for me.

PEEDE: Were you then working with old manuscripts?

FR. COLUMBA: No, I didn’t actually use manuscripts in my first years of research. Just printed editions. Most people interested in older texts work from printed editions of ancient texts. Most scholars rely on the work of an editor who has read the manuscript and transcribed it and produced a nice clean printed scholarly edition with footnotes and so on.

I came to the use of manuscripts in my own research rather late, which is not unusual, and the reason I came to it is I began to get interested in texts which hadn’t yet been edited. One of the fascinating things about the manuscript tradition is there are plenty of texts that have never yet been produced in a printed edition.

It’s not simply that the manuscripts are interesting because they were before all the printed books. More important, there’s a whole body of literature and learning that, for whatever reason, hasn’t found its way into print. So, to look at particular texts, I had to start looking at manuscripts, and I began doing that with microfilms. Later I had the experience of sitting with an actual manuscript in my hands, which I was able to do here, simply to learn the ropes, but then in major libraries around the world, particularly the British Library, and I was doing this even as forces were converging to put me in the job that I have now.

Fortunately, I already had some sense of why manuscripts mattered for the work of scholars. When I found myself being asked to be responsible for this particular project for the community, I wasn’t a neophyte, but I learned so much more as I deliberately integrated manuscripts into my scholarship as much as possible.

That has brought me to the point where I can really explain to people why manuscripts matter and therefore why our work of preserving manuscripts through photography matters.

PEEDE: Talk about that fork in the road when you moved from being a scholar to a preserver of manuscripts.

FR. COLUMBA: I was leading a fairly traditional academic life. It was interesting and fulfilling, but there were other parts of me that weren’t being tapped.

I appeal to the fact that I’m a Texan and there’s something about my Texanity, which interests me in exotic places and discovering new things. Perhaps I shouldn’t blame my home state, but I will blame my mother, who was a very gifted elementary school teacher and my first teacher. When I was a boy, she wallpapered my bedroom with all those maps from National Geographic that nobody ever knew what to do with.

So, I would wake up in the morning and go to sleep at night looking at the world around me. I didn’t deliberately plan to chart a career path that would lead me to many of these places that I saw on those maps, but, as I look back, I realize how that kind of curiosity and awareness of the broader world, which expressed itself when I was young in typical ways, stamp collecting, coin collecting, that kind of thing, how all that would ultimately come together with my academic interests in this opportunity I’ve been given at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library.

PEEDE: What is the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library? How did it come to be?

FR. COLUMBA: Copying manuscripts has long been important to Benedictine monks: We receive a tradition, which means handing on in Latin, then we too pass it on. We want to keep it safe. We want to learn from it. If we can find ways to improve it, we do, and then hand it on.

Early on, we copied manuscripts to make sure that we didn’t lose classics of Latin or Greek literature or early Christian writings and biblical texts.

In the early modern period, it meant finding manuscripts and producing good, printed, critical editions, which French Benedictines did, the Maurist Congregation.

In the Cold War, monks at this monastery were concerned about the situation in Western Europe. During the Cold War, it seemed like there might be World War III. It would be a nuclear war if it happened and, on the monastic side, there was awareness that monasteries in places like Austria still had their manuscripts. They didn’t have a Reformation. They didn’t have a French Revolution.

So, there you have ancient monasteries, very important manuscript collections, and they were sitting in a neutral country between NATO and the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. The original inspiration for our work was just that: Let’s go and microfilm those things just in case.

Our founder, Fr. Oliver Kapsner, went around to Austrian monasteries, asking people if we could microfilm their manuscripts. Most of them thought this was crazy. It seemed newfangled. It seemed like some American idea, which didn’t sit comfortably with their ancient identity until Fr. Oliver found one young abbot, recently returned from studies in Rome, who got it and that’s how it began.

Soon enough people realized this is a good thing to do even if the manuscripts aren’t directly endangered or if the threat to them is of a different kind. After a few years in Europe, we were working in Ethiopia, at a time when nobody saw the revolution coming, but we were working there throughout that whole transition. They had manuscripts in churches and monasteries all across that great ancient Christian country, and under threat from people who might steal them, buy them, or sell them on the black market. They asked for help photographing their culture, and we helped.

A lot of those manuscripts are now gone. Some were taken illegally and put in western collections. Others simply vanished through the dislocation that happens when you have a revolution and a famine. When a tourist comes along and offers you $20 for an old book, that makes a real difference for the life of your family.

That laid the basis for the broader view that we wouldn’t be interested only in monastic manuscripts or Latin manuscripts. We would be interested in Eastern Christian manuscripts, and that sense of openness has informed our recent work.

We moved into the Middle East in 2003, and starting around 2011 we began meeting Muslim scholars and other custodians of Muslim heritage who said, What about us? We realized quickly that these communities coexisted and therefore their libraries and their manuscripts coexisted. In Jerusalem, for instance, in the Old City, there was an important Muslim family library a hundred yards from a Christian monastic library we were working with. How could we say no? How could we say they’re not connected? They’d both been there for centuries.

More recently, our work expanded to the manuscripts of Timbuktu in West Africa, where you find a truly distinctive African Islam, very different from some of the classical forms of Islam that we think of in Egypt or Saudi Arabia. We have also worked with Persian-tradition Islamic material in places like North India, and, in a couple of months, we’ll be starting our first serious project with Hindu and Buddhist materials in Nepal. We work from the conviction that all of this matters: Ideas traveled, people traveled, and religions traveled. If we’re going to understand any of this stuff, for the sake of figuring out how to navigate a very complex world and indeed our own very complex country, we have to have the full picture.

PEEDE: You are sometimes documenting work in conflict zones. Are you ever called upon to preserve the physical manuscripts?

FR. COLUMBA: One of the fundamental principles of how we work is that we partner with local communities who have cared for their own cultural heritage for centuries and often at great cost, so, when we undertake a digitizing project, we don’t actually take the photographs.

We partner with the local people. We provide equipment. We train them. We pay them. They’re handling their own history, and, in a sense, we’re doing the opposite of what some of our American and European predecessors did when they would go to some of these places and effectively go shopping. They picked up all kinds of manuscripts, which then created the great collections of London, Paris, Berlin, the Vatican, and so on. Our principle is that these manuscripts belong to these communities, and decisions about the physical custody and care of the manuscripts are to be made by those communities.

We can occasionally provide some help and at least connect them with partners who can help them with physical conservation, but we’ve never yet had a situation where somebody has asked us to take them away. These manuscripts are so close to the hearts and identity of these communities and, in fact, they’re often quite clever at finding ways to hide and preserve them, as we discovered in Iraq.

We’ve worked there since 2009, partnering with an extraordinary project based in northern Iraq run by a Dominican friar, an Iraqi, who has recently become the Chaldean Catholic archbishop of Mosul. The threat there was the post-Iraq war instability and then the rise of ISIS.

In many of the places where Fr. Najeeb and his team had worked, the locals had only hours or even minutes to escape from ISIS forces and bring with them whatever they could carry. We worried that the manuscript collections had been lost in the chaos. Though there were losses in Mosul and some of the smaller towns, it turns out that these communities were extraordinarily ingenious in either hiding or moving their manuscript patrimony. The digitization efforts had strengthened their conviction that the manuscripts are significant and have to be saved, even at great cost.

PEEDE: How do you decide where to go next?

FR. COLUMBA: Often we’re not the deciders. An opportunity simply presents itself, but when we assess whether it works for us, we’re interested in whether the material coheres with other materials we’ve been documenting, so that we’re creating a meaningful collection of resources for research, as opposed to a collection of one-offs.

Secondly, we like to work comprehensively in a region or culture. Having gone heavily into Ethiopia, we looked to Lebanon, Syria, and southeast Turkey to get an accurate representation of Syriac and Arabic Christian intellectual culture that covered that region.

We are also attentive to the issue of risk. The reason we were interested in helping with the Timbuktu manuscripts, although it was quite a different region for us, is that we were keenly aware that it was an entire religious and intellectual culture at direct risk of destruction by people who considered it to be a threat to their particular interpretation of Islam.

The success of a project depends on finding great local partners because they’re the ones who know what they’re doing in terms of their own heritage. We bring some technical expertise, but it’s the people who are themselves rooted deeply in their own particular culture that make the difference.

PEEDE: Speaking of Timbuktu, you found yourself in some danger there. Tell us what the situation was.

FR. COLUMBA: It was the first time I tried to get to Timbuktu. My colleagues and I had arrived on the U.N. plane, the only way to get there, and gone to a hotel to grab a bite of lunch. It was the only hotel still operating and was thought to be safe, but we found ourselves caught up in an attack on a U.N. base, which was basically next door. This led to eight hours of listening to shooting right outside the room we were hiding in, phone calls to everybody and every embassy we knew, trying to get some help and support.

At some point, somebody said to me, “We really should be praying, shouldn’t we?” And I said, “Well, as matter of fact, that had already occurred to me, but we can certainly do it out loud and do it together.” Eventually the shooting stopped. We were rescued by Swedish U.N. troops, who then took us as prisoners of Swedish hospitality for the next couple of days. Apart from watching the bombing of the Old City of Mosul from across the Tigris, that’s the only time I’ve personally experienced actual conflict. It made me keenly aware of the fragility of the places where we have been working.

The experience only renewed our commitment to Timbuktu. I have been back there twice. As a matter of fact, I’ll be going to Timbuktu next week as part of our effort to do what we can while we can. What we’ve learned in the last ten years, particularly, is that fragility and instability are spreading, not decreasing, and even reaching places like Europe. Consider some of the tensions in our own country. And, so, we really have to get on it and find people who share that interest and establish effective partnerships with them.

PEEDE: Tell us about the cataloging work on the back end.

FR. COLUMBA: Let’s put it this way. When you go on vacation, it’s easy to take a lot of photographs. It’s a lot harder to remember which mountain that was, which church that was, which beach that was. To most people, the exciting

part of our work is in the field, taking the photographs. It’s actually the simplest and fastest part of what we do.

The much harder part is the work of description. We used to call it cataloging, but when you say “cataloging,” people’s eyes roll back in their heads and they pass out from boredom. So we call it “description for the sake of access.” We are providing clues as to what’s in the manuscripts, so that they’re discoverable by people interested in them, including, by the way, members of these particular traditions, who can access their own heritage more easily through our website than by traveling to some of their own places.

A major part of the challenge is scale. We have now photographed hundreds of thousands of handwritten manuscripts. We say 50 million pages. It’s actually much more than that.

It takes a lot of people to describe so many manuscripts. We have tried to establish a kind of fusion of Western approaches with learning from these local communities about what they think is important. How do they talk about what’s in the manuscripts? This aspect is another dimension of what we do.

Another aspect is that we’re often working with texts that haven’t yet found their way into Western scholarly awareness. The result is that we don’t have reference tools to link names and titles to other manuscripts or texts that may be somewhere else.

In a sense, we’re inventing, sometimes it feels like improvising, a whole scholarly infrastructure to enable study of these underrepresented traditions.

PEEDE: How important has the National Endowment for the Humanities funding been to that endeavor?

FR. COLUMBA: The National Endowment for the Humanities has been with us in key points in our development. There was early support in the 1970s for the Ethiopian work. We had a matching grant in the early part of my tenure, which helped put us on a solid footing, for our Malta Study Center, which has incredible archives of documents from that island crossroads. More recently, the Endowment has helped us do the latest and fullest iteration of our Virtual HMML (vHMML), the HMML online platform, which is how we’re making these hundreds of thousands of manuscripts available to the global community.

PEEDE: When you talk of a global community, are you crowdsourcing information on the manuscripts you digitize?

FR. COLUMBA: There might be huddle-sourcing in the sense that there is a small group of people with the needed expertise, but they could be anywhere. The beauty of the system that we’ve created, the vHMML environment, is that it doesn’t matter where they are. If they have online access, they can contribute directly to the work of description through cataloging tools that are built into the system itself.

Also, on every display of every page of every manuscript, there is the opportunity for somebody who’s looking at it to simply click and send us a correction or add a nuance to the description.

PEEDE: So users can send you information, but how do you vet it?

FR. COLUMBA: We’re not a wiki. We have to review the information people send, but we have scholars who can make those decisions. We also have people we can call upon in our global network. Generally speaking, the people who generously offer a correction or an addition are people who know what they’re talking about. We may need to work with the information to make it fit our manner of description, but there is a cumulative effect, and this is the great wonder of an online catalog.

PEEDE: And how important has Endowment support been to your own scholarly career, your own research, your own books?

FR. COLUMBA: I’ve benefited from two NEH fellowships, which supported me on two sabbaticals, the first fairly early in my teaching career. I had the chance to spend a year in Jerusalem, where I wrote a book on John Cassian, a very important early Latin monastic writer. The second one, in 2009, helped me begin the project that I’m still working on, tracing the development of early monastic culture.

The reality of academic funding these days is that sabbaticals are endangered, particularly at small institutions that don’t have large endowments. Typically, you get a semester of paid sabbatical leave, which is not enough to do a substantial project. These kinds of fellowship opportunities let you have a full year to go away and really dig into something. It certainly played a crucial role in my own development, and for many people they are a lifeline.

PEEDE: Let’s talk about HMML, which I see you pronounce as HIMMEL.

FR. COLUMBA: We have a small team here in Collegeville, fourteen people, some of them part time. They receive the photographs, organize them, and prepare them for the work of description and online access. We have four site directors in the field, and many more are involved at the various project sites.

Then, of course, we have the people who maintain the web-based platform, in a sense, the HMML app, that makes all of this available, and then you have the people who help us find supporters for our work through development efforts.

A growing element of what we’re trying to do is find new ways to introduce people to the significance of what we’re doing and explain why it has a direct impact on how we view the modern world and how it might help us to make wise decisions, in some cases wiser than our predecessors, who might have viewed religious difference through the lens of conflict or conversion. There may be lessons here to teach us in a more positive sense on what it means for communities to coexist and even more than coexist, to create together a functioning society.

PEEDE: Does your work give you hope?

FR. COLUMBA: I don’t want to say that the work gives me hope. I want to say that the people we work with give me hope. They may represent a range of religious traditions, but all the people who work with us share a conviction that human knowledge, whatever its origin, is important. That gives me hope because if we’re going to get anywhere, we’re going to have to listen and learn, rethink our understanding of the world, perhaps correct it, perhaps be strengthened in our sense of who we are. It’s going to require continual learning for us to get where we need to be.

PEEDE: I know you are just starting to work on your Jefferson Lecture, but are there two or three ideas or sentiments that you hope to impart?

FR. COLUMBA: There is a deep anxiety in the environment I live in that the humanities are endangered and that we need to make a case for their importance. It’s also important to remember where the name “humanities” comes from. Humanities refers to the study of topics or fields of inquiry which address those things which are most fundamentally important to human beings. We have to find ways to bring our discussion of the humanities back to human realities and human questions rather than presenting it as some sort of effete specialty that has no actual relevance for how we live. The humanities are about how we live because the humanities are about humans. One of the things I need to do in the Jefferson Lecture is to bring it home. I need to speak as a human being about what’s important to me, and remind people that there are things important to them, and that there are resources out there to help us surface and explore what we so often lack language to describe. That’s what the humanities can help us do.