As the sun sets on the second Wednesday of July 2023, the relentless Mississippi humidity casts a sticky, sweltering blanket over the Pearl River Amphitheater, home of the Choctaw Indian Fair. Chief’s Hour has just concluded, and one of the most anticipated events of the fair, or quite possibly the year, is moments away. With much excitement and anticipation, family, friends, and other fairgoers eagerly line their lawn chairs around the stage or place blankets in the grandstands to reserve the best seats to watch twelve young Chahta Ohoyo (Choctaw young ladies) vie for the title of the 2023–2024 Choctaw Indian Princess. All eyes are fixed on the stage as the opening walk begins and the upbeat tempo fills the amphitheater. The contestants wear white outfits adorned with intricate beadwork from earrings and necklaces to belts and hats. Against the backdrop of purple, pink, and white floral arrangements and stage decor, the girls shine as they introduce themselves to the audience.

Young women ages sixteen to twenty compete in the following categories: interview, on-stage personal presentation, on-stage question, and traditional wear. The young Choctaw are all radiant and charming as they showcase their attire, cultural knowledge, public speaking skills, and poise. Over her year, the Choctaw Indian Princess will attend ribbon-cutting ceremonies, parades and educational initiatives, and speaking engagements on tribal and nontribal grounds. She must be able to converse with different groups of people in a respectable and knowledgeable way. Since the crowning of the first Choctaw Indian Princess in 1955, Patsy “Pat” (Sam) Buffington, the princess has been an exemplary representation of the Mississippi Choctaw people.

By night’s end, one contestant stood out. She had a commanding stage presence, a deep appreciation of Choctaw culture and tradition, knowledge of the Choctaw language, a calm and collected demeanor, and an overall beautiful performance. The emcee announced contestant #5, Nalani Luzmaria Thompson, who stepped forward to be crowned the 2023–2024 Choctaw Indian Princess.

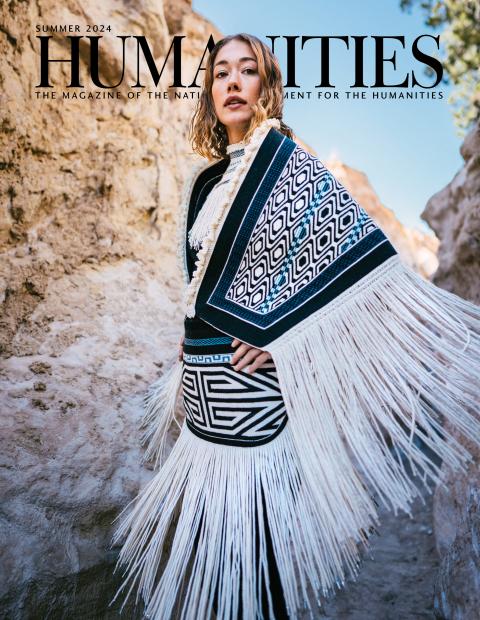

Ten months into Princess Nalani’s reign she recalls the moment. “In pictures, I saw the poise and grace that my grandmother—my inspiration—Anita Jim McCombs displayed during her 1982–1983 reign as Choctaw Indian Princess, and I wanted to be like that, and I wanted to honor her. During the personal presentation part of the pageant, I wore an 18-year-old traditional dress and apron that my late great-grandmother made, and I wore the bead set that my mother, her mother, and grandmother made. So it was a three-generational set.” Nalani focused on sharing the Choctaw language, first using the Chahta word and then giving the English translation. During her pre-recorded explanation of her Choctaw traditional attire, she used the words Chahta Iloka (Choctaw dress), shikalla (bead set), kanomi (cousin). Highlighting her native language for Chahta and others in the audience was important to Nalani.

Filling the role of the tribe’s ambassador is no small feat. The woman must represent not only herself, her family, the tribal chief, the tribal council, and the Choctaw people, but, at times, all of Indian country as well. Princess Nalani, as she has come to be known, said, “Little girls dream of being a princess. And so it’s one of those big things in our community because we get to speak for those little girls. . . . We are a role model not just to them, but also to teenage girls and even older women because they look at us and think our traditions are still alive through this person.” The Choctaw Princess is a symbol of resilience, not only of the Mississippi Choctaw, but of every other Indigenous tribe as well.

The Choctaw have endured brutality, outside corruption, removal, assimilation, and worse. In the centuries before colonization, the Choctaw were the land keepers of what is today the southeastern United States. From the first contact with Europeans, in 1699, the Choctaw people were thrust into wars (the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War), bad faith treaties that resulted in the tribe’s removal to Oklahoma and forced displacement from land taken by white settlers (the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek), and sickness (the 1918 influenza epidemic). Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the constitution of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians was ratified before being officially recognized by the federal government in 1945.

Chief Phillip Martin, who served from 1979 to 2007, was the driving force behind the tribe’s fight for self-determination. He helped usher in significant economic progress that our tribe benefits from today. Our ancestors fought to stay in our homeland during the forced removal in the nineteenth century, and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is now stronger, more resilient, and more economically successful as the top employer in Neshoba County through entities such as its health center, schools, services, and the Pearl River Resort and Casinos. From securing homes, programs, schools, child care, hospitals, and public and fire safety for its members, the tribe has much to be proud of. Princess Nalani remarks, “Keeping our culture alive and passing it down to younger generations is very important because it is a part of us as Chahta people. Our regalia, our songs and dances, and our language are unique to us, and that’s something that cannot be taken away.”

I feel very fortunate to have had close relationships with a few princesses—the closest being with my mother, Misty Brescia, the 1993–1994 Choctaw Indian Princess. When we lived in Georgia, she came to my fourth-grade class and gave a presentation about the tribe. The pride I saw as she wore her sash and showed off her own beaded crown was a sight for my young eyes. Her passion for her tribe was evident as she related her experience as the princess but also the Choctaw creation story, the history, and the cultural practices. She dressed me in full regalia, a red cotton dress with white diamond embroidery to represent the diamondback rattlesnake, a snake that the Choctaw honor, as, historically, they kept critters away from growing crops. I wore a combination of beadwork that was once worn by my grandmother, mothers, aunts, and cousins. She also brought stickball sticks to demonstrate our traditional game. My mother’s example allowed me to educate classmates and teachers more meaningfully. Today, my mother is the director of the Office of Public Information for the tribe, which handles, among many other responsibilities, all events and scheduling of the Choctaw Indian Princess. As her daughter, I am sometimes “assigned to volunteer” as the princess’s escort—to ensure the princess arrives at the events on time, that the regalia is perfect, to take photographs, and be there if anything else is needed.

My favorite memory of my time as Princess Nalani’s escort was the Saturday of the 2023 Choctaw Indian Fair. It was the final day, so everyone was tired. Between heats of the Iron Warrior Competition (a type of Ironman Competition where men and women compete in a timed obstacle course), Nalani greeted guests, posed for photos, and signed autographs. A little girl’s moccasin came untied, but she was so excited to see the princess that she ran over to get a hug anyway. After hugging her and asking the little girl about her favorite part of the fair, Princess Nalani sat on the ground in full regalia and tied the child’s moccasin. To many, it was a simple act of kindness, an almost meaningless gesture. But with the unbearable heat and uncomfortable concrete ground, the humility, dedication, and respect shown by Princess Nalani were evident on the child’s face. Those qualities translate through her reign and her life. In each outing I have seen in her that same pride I saw years ago in my mom’s eyes. Being selected as a Choctaw Indian Princess affords you membership into this remarkable group of Chahta Ohoyo. It is a title Princess Nalani holds dear and will have forever.