In the world of showbiz, there are stars, and, then, there are constellations.

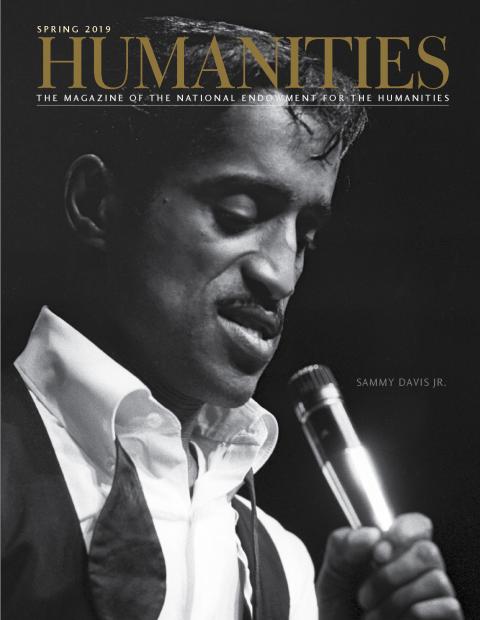

With his diminutive frame, Sammy Davis Jr. emanated enough star power to put the Hubble telescope out of business. Imagine what it must be like to star in a Broadway musical. Then imagine you have to perform ten songs, four of them solos. How about we give you a meticulously choreographed fight for the finale? Oh, and while you’re doing eight shows a week (including two on Wednesdays and Saturdays), you’re recording albums, doing charity benefits, and, to top it off, smoking three packs of cigarettes a day. But wait, as the saying goes, there’s more: You’re collaborating with a pair of biographers on your memoirs every night into the wee small hours.

This was the life of Sammy Davis Jr., beginning in the spring of 1964 when he took on the lead in a musical update of Clifford Odets’s Depression-era drama Golden Boy. Crafted specifically for Davis’s talents by the hot Broadway songwriting team of Charles Strouse and Lee Adams (Bye Bye Birdie) and tailored by Odets to capture the racially charged boxing era of Sugar Ray Robinson and Cassius Clay, Golden Boy was a rare topical show on Broadway during the 1960s, a decade more hospitable to genteel entertainment. The lead character of Joe Wellington (whimsically renamed from Odets’s original Italian hero, Joe Bonaparte) required a stage personality of considerable talent, courage, and endurance. Which is where Sammy Davis came in.

What do Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Dinah Shore, Tony Bennett, and Sammy Davis Jr. have in common? Well, obviously, they were among the stellar lights of contemporary popular music in the first three-quarters of the twentieth century. But only one of them had the guts to commit to the grueling schedule of a run on Broadway. This wasn’t vanity on Davis’s part; it was indicative of the kind of determination that drove him throughout his career—to accomplish what no one else had ever accomplished in the entertainment field. It required more than physical stamina, given the additional task of confounding the racial barriers Davis faced from the moment he entered the profession as a four-year-old tap dancer in segregated Depression America. As he wrote in Yes I Can: The Story of Sammy Davis, Jr.—the memoir he was dictating at four in the morning during Golden Boy—“I’m going to get so big, so powerful, so famous, that the day will come when they’ll look at me and see a man—and then somewhere along the way, they’ll notice he’s a Negro.” This was the octane that fueled Sammy’s burning ambition.

In his early showbiz years, Sammy forged the prodigious tools of his trade. “In those days in show business, speaking medically, the job was not to be a specialist, but a general practitioner—you had to do a little bit of everything, know how to say a line, sing a song, tap a dance, do a joke,” he later observed. Just as he was composed of a cornucopia of talents, Sammy was many, many people and with just as many contradictions. In a July 1966 issue of that inestimable chronicle of American culture, MAD magazine, Sammy’s existential dilemma was brilliantly crystallized in a spoof of ethnic stereotyping called “Stereo-Typecasting By The Numbers.” In it, the writer and artist attempted a kind of numerical taxonomy. When it came to Negroes (the largely accepted term of identification back then), the magazine averred that one Negro was “token integration,” two was a “championship bout,” three was an “Emerging African Nation,” and four was “Sammy Davis, Jr.” This was his paradox: He was, at once, as talented as four men put together, and he had to work as hard as four (ostensibly white) men to achieve what he achieved in postwar America. Sammy Davis’s personality was so complex, he taxed the taxonomy.

The trajectory of Sammy Davis’s many lives has such a long arc that it streaked across numerous flashpoints in American history. Davis started in vaudeville gigs, dancing with his father and uncle as the Will Mastin Trio in the “Chitlin Circuit,” where he essentially abjured any kind of schooling to support his family during the Depression. He absorbed bullying and prejudice while serving in one of the first integrated units in basic training in the wake of World War II; faced numerous boycotts and slurs as a black entertainer in the late forties and fifties, even at the nation’s most sophisticated clubs; he was essential to the rise of Las Vegas as a location and an industry. As a member of the Rat Pack, Sammy was part of an imperfect allegory of integrated America; advocating and supporting the candidacy of John F. Kennedy, Davis was quickly denied a seat at Camelot’s entertainment Round Table when his marriage to a white actress, May Britt, proved too incendiary for the Southern Democrats that Kennedy was gingerly courting.

After Martin Luther King Jr. came backstage to visit at Golden Boy, Davis became an activist during the civil rights movement (although he was initially extremely reluctant to go south of the Mason-Dixon Line); by the time of King’s assassination, he was transformed into an impassioned apostle for the struggle, helping to raise more money for the cause than any other celebrity, black or white. When Sammy befriended Richard Nixon at the beginning of his 1972 election campaign, it created a massive rift between him and the black fan base that had supported—idolized!—him for decades. Then, predictably, perhaps, for such a high roller, he was swept up into the heady world of drugs and dissolution that represented the excesses of the 1970s. Only in the mid 1980s did he straighten himself out; alas, a major career comeback was denied him when he contracted throat cancer and died in 1990. Ironically, Sammy Davis was the youngest member of the Rat Pack, the epitome of brash ebullience, and yet nearly all of the other members outlived him.

Davis was a veritable human Venn diagram. He overlapped with most of the key figures in American history and culture in the twentieth century, often as a transitional figure between two extremely antithetical personalities. He bestrode Bill Robinson and Michael Jackson; Frank Sinatra and James Brown; Ethel Waters and Kim Novak; Eddie Cantor and Harry Belafonte; Clifford Odets and Jerry Lewis; Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis; John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon; Martin Luther King Jr. and Archie Bunker.

Clearly, his life also bestrode triumph and tragedy. “You are like two characters in the same play,” Sinatra supposedly said to him, “Your talent is the hero and your excess is the villain.” Sammy was an unbeatable talent, the showbiz equivalent of a running back who could routinely charge downfield to pick up ninety or even a hundred yards a play. Except society kept moving the goalposts—now 120 yards, now 140, and so on.

In writing the PBS American Masters documentary, Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me (supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities), I came to sympathize with this diminutive giant, though I never knew him or had the privilege of seeing him perform live. He was an aspirational human being, not only for himself, but for every performer of color who came after him. In a strange anomaly in the 1970s, he was briefly signed by Motown Records, though he was an incongruent fit with that most “with-it” of labels. Typically, he chose a show tune for one of his few singles for the company, a ballad from The Rothschilds, a musical about the aspirational Jewish banking dynasty. “In my own lifetime / I want to see the walls come down / And then I’ll rest,” goes one refrain.

In Davis’s own lifetime, a few of his dreams came true; some came true after; many have not yet come to pass. But the important thing to embrace about Sammy Davis, Jr. was yes, he could, but more inspirationally, yes, he did.