Much has happened in Edward Pratt’s life since he graduated from Southern University, Baton Rouge’s historically black institution of higher education, in 1975.

After a long newspaper career, he took several public relations jobs, including a stint as SU’s spokesman. Pratt, a 63-year-old husband, father, and grandfather, now works in Louisiana state government and keeps his hand in newspapering as a weekly columnist for his hometown paper, the Baton Rouge Advocate.

Despite the decades that have passed since his time as a Southern student, Pratt mentally revisits the campus every autumn when a grim memory resurfaces.

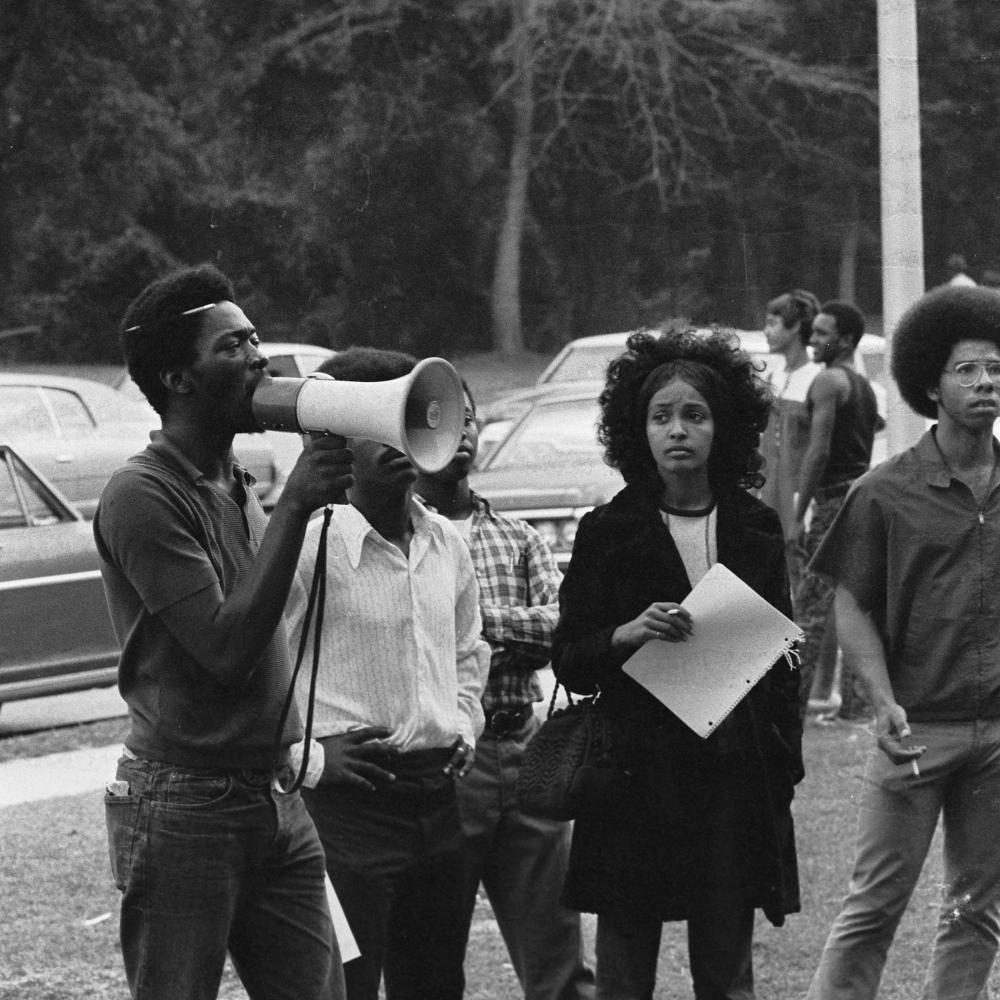

During Pratt’s first semester at Southern, on November 16, 1972, he was nearby as two fellow students were shot to death during a campus protest. The confrontation between unarmed student protesters and dozens of law enforcement officers, which included men in military-grade gear and an armored car, “was like something out of a bad dream,” Pratt says. An official inquiry traced the gunfire to a group of local sheriff’s deputies who had responded to the demonstration. Students who witnessed the protest, including Pratt, said it had been peaceful, which made the use of force baffling.

No one was ever charged in connection with the incident, which left freshmen Denver Smith and Leonard Brown dead from shotgun wounds. The deaths have haunted Pratt ever since.

He recalls the date of the shootings almost as easily as his birthday or wedding anniversary. Pratt wants others to remember, too—so much so that he typically writes about Smith and Brown each November for his newspaper column or on social media.

“I owe it to Smith, Brown, and their families to remember them,” Pratt wrote last November in his Advocate column. “I was a fellow freshman, and we were in college and had big dreams. They never got a chance to chase theirs.”

Pratt’s efforts to keep Smith and Brown in public memory have now gotten a big boost. The Southern protest figures prominently in a new documentary, Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges & Universities, slated to air on PBS on February 19 as part of the Independent Lens series.

Directed, cowritten, and produced by acclaimed filmmaker Stanley Nelson, Tell Them We Are Rising chronicles the sometimes tragic and often triumphant history of America’s historically black colleges and universities, or HBCUs.

The title of the film comes from a reported exchange between Oliver Otis Howard, the founder of Howard University, and newly freed slaves after the Civil War. As the story goes, when Howard asked what he should say to Americans up north about the state of African Americans, 13-year-old Richard Robert Wright stood and said, “Tell them we are rising.”

“My parents were the product of HBCUs,” Nelson says. “For generations, there was no other place our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents could go to school. Yet higher education has always been a prerequisite for entering and competing in mainstream American society. I set out to tell a story of Americans who refused to be denied a higher education and—in their resistance—created a set of institutions that would influence and shape the landscape of the country for centuries to come.” Southern University, which opened in 1880 with 12 students, is an important chapter in the story Nelson captures on film.

Nelson’s previous films, which often focus on the African-American experience, include Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, Freedom Summer, and The Murder of Emmett Till. President Barack Obama presented Nelson with a National Humanities Medal in 2014.

“What I’m trying to do is part detective,” Nelson then told HUMANITIES. “There’s a feeling we all know about the civil rights movement. So part of it is finding new and exciting voices that we haven’t heard.”

In a recent phone interview, Nelson, a 2002 MacArthur fellow, points to the 1972 Southern shootings as a tragedy that’s often been overlooked. “Like so many people, we were shocked,” he says of the research about the incident he and his production team uncovered.

Film footage of the shooting offers a gripping historical record of Smith and Brown’s final moments. As gunfire erupts, the crowd of students outside of the university’s administration building scatters, but two students remain behind, lying on the ground.

“We thought they had got run over,” Pratt recalled. Soon, the gunshot wounds the two men had sustained revealed a darker truth.

“I was saddened, but not surprised by it,” Nelson says of the deaths, which have eerie parallels with more recent controversies surrounding police shootings involving African Americans. “The only difference now is that people have cell phones. It just reverberates to a greater degree because of what’s been happening in the past couple of years.”

The student activism at Southern in 1972 was part of a larger protest movement on other HBCU campuses. “The black college campus in the 1960s is getting more and more complex,” historian Jonathan Holloway says in Nelson’s documentary. “They’d been already trying to change the world outside and changing a society that was about separation of the races. When you get to the late 60s and early 70s, that energy for change starts to turn inward.”

“A lot of the conflict that’s starting to happen is between the students and the administrators, students and the boards of trustees. . . . That makes for some pretty hot times on black college campuses,” says civil rights advocate and scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, who also appears in Tell Them We Are Rising.

As one of the first members of his family to attend college, Pratt began his freshman year at Southern with great expectations. Like many college students, he embraced campus life as a source of personal awakening. “I met people from around the world there,” Pratt says. “There was even an African prince on campus.” The diverse backgrounds of the student body fueled stimulating discussions about culture, family, and politics. Pratt loved it. Meanwhile, at Southern that autumn, a movement was growing.

“For 10,000 students, we didn’t have enough buildings,” Pratt recalls. The space shortage forced many Southern students to take classes on Saturday, a hardship for those who held weekend jobs to pay for school and support families—or even worked on farms back home. “A lot of the kids who went to Southern were from farm areas,” he says. “A lot of those kids were sharecroppers’ children. It was tough for them to even get to college.”

In 1972, the difference between life at Southern and life at Louisiana State University across town was stark, historian Martha Biondi tells viewers: “Southern University in Louisiana was the largest public black college in the United States. There was a black president and black administrators, but it was under the control of the white elected officials in Louisiana, who only spent half as much per pupil as they did at the predominantly white LSU.”

Beyond their complaints about a lack of resources and facilities at Southern, students had other concerns. They also wanted classes that included more content about African-American history and culture—a reflection of the black consciousness movement sweeping the country. “We had just come out of the civil rights movement,” Pratt says. “A lot of the students had come out of predominantly white schools,” where the black experience wasn’t included in the curriculum, he adds.

For the most part, students who raised these issues at Southern felt that their suggestions fell on deaf ears, Pratt says. “What you had were old-guard administrators who didn’t want to rock the boat. The students saw no support coming from the administration. The students began to march on campus. Many of us tuned it out until we saw it right in front of us.”

Like many university communities in Louisiana, Southern’s students and alumni venerate college football as a civic religion. To protest conditions on campus, student activists marched on the field and stopped a Southern football game. “When I saw that students were willing to make that kind of sacrifice, I knew this was serious,” Pratt says.

As a leader of the protest movement at Southern, Fred J. Prejean helped organize a boycott of classes. “I’m just an ordinary, sane, gutsy person who believes in fighting for what I believe in,” Prejean told the Advocate in 1996.

When Prejean and his fellow students wouldn’t end the boycott, local authorities barred him from entering campus. Even before the sun rose on November 16, 1972, tensions at Southern were boiling. As part of the dispute, law enforcement officers took Prejean and three other protest leaders into custody.

“Somewhere’s between two and three o’clock in the morning, I received a knock on my door, which turned out to be the police, and they handed me a warrant for my arrest,” Prejean recalls in Nelson’s film. “I was scared. I had never been to jail before. I didn’t know what to expect.”

Later that day, protesters occupied Southern’s administration building—a move that Pratt and other witnesses have described as peaceful. Meanwhile, the National Guard, along with area local law enforcement officers, had arrived on campus in force. Governor Edwin Edwards had marshalled the buildup after days of tensions at Southern.

“Black colleges were particularly vulnerable to police invasion,” says Biondi, “because white politicians were quick to call in the police, and quick to look the other way when police used deadly force.”

The law enforcement presence on campus involved military-grade equipment, including a large armored vehicle nicknamed Big Bertha. The scale of the tactics only served to further inflame anxieties, Pratt said.

Dalton Honoré, one of only a few area African-American law enforcement officers at the time, was on campus that day as a Baton Rouge sheriff’s deputy. Honoré, another commentator in the documentary, says authorities had gotten a phone call saying that the university’s president, Leon Netterville, “was being held hostage in the administration building that had been taken over by students, and we were ordered to free the hostage. . . . It came as a surprise to me . . . that afternoon that Dr. Netterville was not on campus.”

As the standoff between authorities and students in and around the administration building intensified, Pratt was at the student union visiting with friends. The jukebox was playing Jermaine Jackson’s version of “Daddy’s Home,” a ballad that listeners of the time embraced as an anthem for soldiers longing for home during the Vietnam War.

“Suddenly, the music stopped,” Pratt recalled in a 2001 newspaper column. “Someone had ripped the jukebox’s electrical cord out of the wall.”

One student climbed on a chair and urged the others to head to the back of the campus, where the administration building was located. “The scene awaiting us was unsettling,” Pratt told readers. “There were ranks of State Police and sheriff’s deputies on one side. . . . Facing them, about 30 to 40 yards away, were hundreds of chanting students. Most of the officers’ attention was focused on the Administration Building because student protesters were occupying the building.”

What happened next is unclear. In the documentary, Honoré points to a state trooper’s lobbing of a tear gas canister into the students, then a student lobbing the canister back, as the spark that set off the violence. What is known is that the law enforcement response to the protest ended in gunfire, with Smith and Brown, who had been outside the administration building as bystanders, losing their lives.

The two men’s bodies had been removed by the time that Smith’s sister, who had been in the administration building with the protesters, came out. She could see the blood on the ground and knew that something terrible had happened.

As she walked back to her dorm in grief with fellow students, Smith’s sister learned who had died. “They said, ‘You know that was your brother, huh?’ I said ‘What?’ I went numb,” Josephine Smith-Jones recalls in the documentary.

Michael Cato, a Southern student at the time who also appears in the documentary, was dumbfounded by the deaths. “They were exercising their constitutional rights, and they got killed for it,” Cato says.

The unfolding violence had paralyzed Pratt with fear. “I was too scared to move,” he says. He spotted Smith and Brown’s bodies. “A girl started screaming. . . . If you looked closely, you could see blood coming out of their heads.”

Pratt says the violence was all the more mystifying because, in retrospect, it seemed so preventable. If Governor Edwards or the university administration had been more open to talking with students, their differences wouldn’t have descended into bloodshed, Pratt maintains.

Edwards, who is interviewed for the film, has a different view. “The accident wouldn’t have happened at all if they had not taken it upon themselves to occupy the president’s office. . . . That was the triggering mechanism,” he says of the protesters.

Eventually, the tear gas forced Pratt and the students near him to flee. He made it off campus and back home, finding a family relieved that he was safe. In a time before mobile phones, there had been no quick and easy way for parents to know if their sons and daughters had survived the chaos.

Southern endured other losses that day. A fire broke out in the registrar’s office, and authorities linked the incident to students. The campus was closed until the following January, Pratt recalled, which gave him and his fellow students a lot of time to reflect on an event that had changed their lives.

“He was never part of the movement at all,” Smith-Jones says of her slain brother. “If I hadn’t been involved, my brother never would have been there.”

Prejean, who had been in jail the morning Smith and Brown were shot, faced his own grief. “It shocked me into seeing the reality of how far people will go to maintain the status quo, even if it means keeping others down in a lesser condition,” he told the Advocate. “For a number of years I was in a state of depression. I didn’t want to go anywhere, talk to anybody.”

In the weeks after the shooting, as Southern stayed closed, Pratt considered leaving the university and enrolling at LSU. But he opted not to, deciding that the best way to extend Smith and Brown’s legacy would be as an active member of Southern’s community.

The special bond that students of historically black colleges and universities feel with their campuses is a prevailing theme in Tell Them We Are Rising. Although the film chronicles the Southern tragedy and other low points in the history of HBCUs, the tone of Nelson’s documentary is mostly positive, focusing on the resilience of African-American students against long odds.

Pratt worries that the kind of history featured in Tell Them We Are Rising is in danger of being lost among today’s students. Southern has taken steps to keep Smith and Brown’s legacy alive. Last March, the university’s board of supervisors voted to award posthumous degrees to the two slain students. During a dedication ceremony in 1992, the student union on campus was renamed the Smith-Brown Memorial Union. Family members of both men laid a wreath at the site where they died.

And every November, Edward Pratt tries to publicly share the story of Brown and Smith. He wrote, “I want to mark this day as long as I can. I owe it to the memories of two classmates whom I never talked with, but whose unwarranted killings I want to talk about as long as I have breath.”