Late in the winter of 1959, poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton were both auditing a creative writing seminar at Boston University led by Robert Lowell. The three were very different writers, but each had recently embraced or was gravitating toward a new style of poetry dubbed confessional for its mining of personal experience and its tendency to use a direct form of address. The afternoon sessions around a table in a classroom overlooking Commonwealth Avenue included five registered students and about fifteen who were auditing.

Lowell at the time was considered one of America’s leading men of letters for such poems as “Skunk Hour” and “Words for Hart Crane.” His groundbreaking Life Studies had just been published. Plath was publishing poems in various magazines and journals and would have her first book, The Colossus, come out the following year in England. Sexton had been publishing regularly in periodicals and was about to see her collection To Bedlam and Part Way Back come into print.

The three shared not only the same literary vocation but personal experience with mental illness. All three, in fact, had been patients in McLean Hospital, near Boston: Plath was moved there after shock treatments at another facility; Sexton for five days of extensive examinations; Lowell, a manic-depressive, checked himself in at various times, including sometime soon after the last class with Plath and Sexton in April 1959.

The creative writing seminar came at a critical juncture for Plath, who was in a period of transition between the kinds of poems that she had already written, slowly and methodically, for the book The Colossus and the kinds of poems she would write very fast for the book Ariel. The poems in The Colossus tended to be scenes drawn in exactitude, while the poems of Ariel, as the title implies, were spirited and written at breakneck speed—they were, in Lowell’s words, “events rather than records of events.”

The dynamic of the seminar briefly held Plath, Sexton, and Lowell together in a tight orbit. Sexton caught Plath’s attention by fearlessly taking up personal aspects of her own life as her subject, and Lowell had a guiding hand in releasing Plath from self-imposed structural constraints on her verse. In class, Sexton, by her mere presence, was a help to Plath with substance, while Lowell was a help with form. Heather Clark meticulously covered every inch, seemingly, of the terrain of Plath’s passage through this world, including the seminar with Sexton and Lowell, in her NEH-funded biography, Red Comet.

Plath was a writer’s writer: She painstakingly labored over sound and cadence in her poems; she wrote a fine, perspicacious novel, The Bell Jar, based largely on her experiences of working for a summer at Mademoiselle magazine in Manhattan; she read widely and planned out ideas for children’s books and other novels; her posthumously published second collection of poems, Ariel, secured her place in the pantheon of American poets; and she kept insightful and introspective journals and engaged in a lively daily correspondence. Collected Poems earned her, posthumously, the Pulitzer Prize in 1982. The scope and quality of her output are impressive, given her short life, which ended in suicide, at the age of thirty, in February 1963, in a house in London that had once belonged to the Irish poet William Butler Yeats.

In June 1958, Howard Moss at the New Yorker accepted two of Plath’s poems for publication. Plath and her husband, fellow poet Ted Hughes, were determined to live by their pens, but it had been difficult, especially for Plath, a housewife who planned on having children soon. Hughes had already gained renown in England with the critically well-regarded The Hawk in the Rain. Both had to accept part-time jobs to make ends meet. The payment from the New Yorker, then, bolstered not only Plath’s self-confidence but also provided much-needed income.

Sylvia Plath saw herself as a prose writer as much as or even more so than a poet. She felt her poems, as Clark notes in her biography, had one “main flaw,” which she identified in her journals as a “machine-like syllabic death-blow.” Lowell’s classes benefited her writing generally, allowing her, surprisingly perhaps, to circumvent her blocks in crafting prose. She was learning, she would write, a “new language” in the classes, and was particularly impressed with a poem Lowell read out loud, “Waking in the Blue,” based somewhat on his experiences in the mental ward. Written in the new style that would characterize Lowell’s poems in Life Studies, “Waking in the Blue” demonstrated what he had been preaching to the class, especially his lesson to Plath not to use form as a crutch.

Azure day

makes my agonized blue window bleaker.

Crows maunder on the petrified fairway.

Absence! My heart grows tense

as though a harpoon were sparring for the kill.

(This is the house for the “mentally ill.”)

Lowell was demonstrating, too, the powerful energy that a poet could instill in their work by allowing subliminal, even violent, forces to rise to the surface. Lowell was confessional in the sense of possessing self-knowledge, as was Sexton. Plath was heading in that self-exploratory direction as well, though, as Clark points out, Plath’s poetry was often highly surreal and is sometimes overcategorized as being purely confessional.

Plath, a graduate of Smith College, stood out in the seminar for seemingly having read and understood every author in the canon. Erudition aside, her poems were solid, concrete observations of her surroundings, and the quality of the precise images in poems she had published by that time, such as “The Manor Garden,” was decidedly photographic: “The fountains are dry and the roses over. / Incense of death. Your day approaches./ The pears fatten like little buddhas. / A blue mist is dragging the lake.”

She mentioned in class her favorite poet was Wallace Stevens, and she had the facility to easily detect the influence of poets from the canon in other students’ work. She had been reading widely, especially, at one juncture, tragedy, and could speak with confidence in class on many subjects. After graduating from Smith, Plath taught there, too, briefly, and was well equipped to appraise Lowell as a teacher, one time noting that, in his “mildly feminine ineffectual fashion,” he allowed statements from students to stand that she as a teacher would not. Lowell protégée Kathleen Spivak observed, though, that Plath never cracked a smile, not even at Lowell’s jokes.

In stark contrast with Plath, Anne Sexton had little or no training as a poet, was vivacious, even flirtatious, and received praise from established poets such as Pulitzer Prize-winner W. D. Snodgrass, with whom she studied in the summer of 1958 at the Antioch Writers’ Conference. Snodgrass is credited with being, perhaps, the first of the confessional poets. Sexton at the conference was, one teacher noted, “bawdy and funny.” And to another, she was “Dashing. Flamboyant. Spectacular. A house afire.” Her own family was unsure about her newfound zest for writing poetry—fearing that it was another symptom of an ongoing addiction to booze and pills. She told her doctor her husband was furious with her for arguing that “not just writing poetry but being with poets was essential to her well-being.” Sexton had left her children in the care of her mother-in-law in Wellesley to attend the Ohio conference, where she was flirting with a fellow student and with Snodgrass.

Back in Massachusetts again, Sexton attended Lowell’s seminar in the fall and continued the next spring. Plath paid close attention to Sexton but noticed a “looseness” in many of her poems. Sexton was recognized by established poets for having good bursts of originality and perception, Ted Hughes noting, too, in 1962, that “the short sharp poems are the best.” The influence of Lowell on Sexton in the seminar, beyond his recognition and praise for her formal skills was, as she told Snodgrass, “teaching me what NOT to write—or mainly. I am learning leaps and boundaries.”

During the weeks of the seminar in Boston that spring, Plath and Sexton, joined by fellow poet and seminar attendee George Starbuck—a Yale Younger Poets prizewinner who had, unjustifiably in Plath’s view, beaten her out for the prize that year—would head afterward to The Ritz, where they parked in the hotel’s loading zone while enjoying their regular three-martini gatherings. Clark relates that Sexton would quip that it made sense to park in the loading zone since they were all there to get loaded.

“Like Lowell,” writes Clark, “Plath recognized Sexton’s revolutionary talent at just the time she was trying to shed her formalist tics. For years Plath had castigated herself for not getting more ‘life’ into her poems. Here, suddenly, was another Wellesley housewife—poet, suicide survivor, and asylum patient who had effortlessly achieved the aural and emotional effects she herself tried so hard to create.”

Lowell’s writing didn’t influence Sexton as much as his classroom presence and teaching, since she hadn’t been reading much poetry, but Plath had read Lowell, even while at Smith. She donned red silk stockings to attend a reading Lowell gave there, and, evidently, she was still imbibing from his work. Lowell’s poem “Thanksgiving’s Over” is in the same angry vein as what is without any doubt Plath’s best-known poem, “Daddy.” In Lowell, it’s, “You are a bastard, Michael, aren’t you! Nein, / Michael. It’s no more valentines.” The line in “Daddy” drips with similar venom: “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” The willingness in Plath to mine the subconscious for subject matter in poems in Ariel, we can safely suppose, was encouraged, if not triggered, by Lowell.

A couple of years before Lowell’s seminar, Sexton had become close friends with poet Maxine Kumin, just three years Sexton’s senior, who read Sexton’s poems and reacted favorably and encouraged her. Sexton had been writing poetry at that point for only about a year. Kumin’s was the kind of encouragement Sexton most craved, valid approval from a real poet. It was about this time that Sexton penned “Music Swims Back to Me,” which she gave to Kumin to read shortly after completing it. “I don’t know whether it’s a poem or not,” Sexton said over the phone to Kumin. “Can I come over?” Sexton took the poem to Kumin, who sat down and immediately read it. Diane Middlebrook, in her biography of Sexton, recounts Kumin’s reaction: She “marveled that the poem had come to Sexton ‘almost whole—just occurred on the page, and was still quivering.’” In a fiercely original and creative twist, it’s the music that remembers, rather than the woman speaking, during the poet’s first night in an asylum:

Music pours over the sense

and in a funny way

music sees more than I.

I mean it remembers better;

remembers the first night here.

It was the strangled cold of November;

even the stars were strapped in the sky

and that moon too bright

forking through the bars to stick me

with a singing in the head.

“Music Swims Back to Me” made it into To Bedlam and Part Way Back, in spite of Lowell’s “pruning,” with little or no revision.

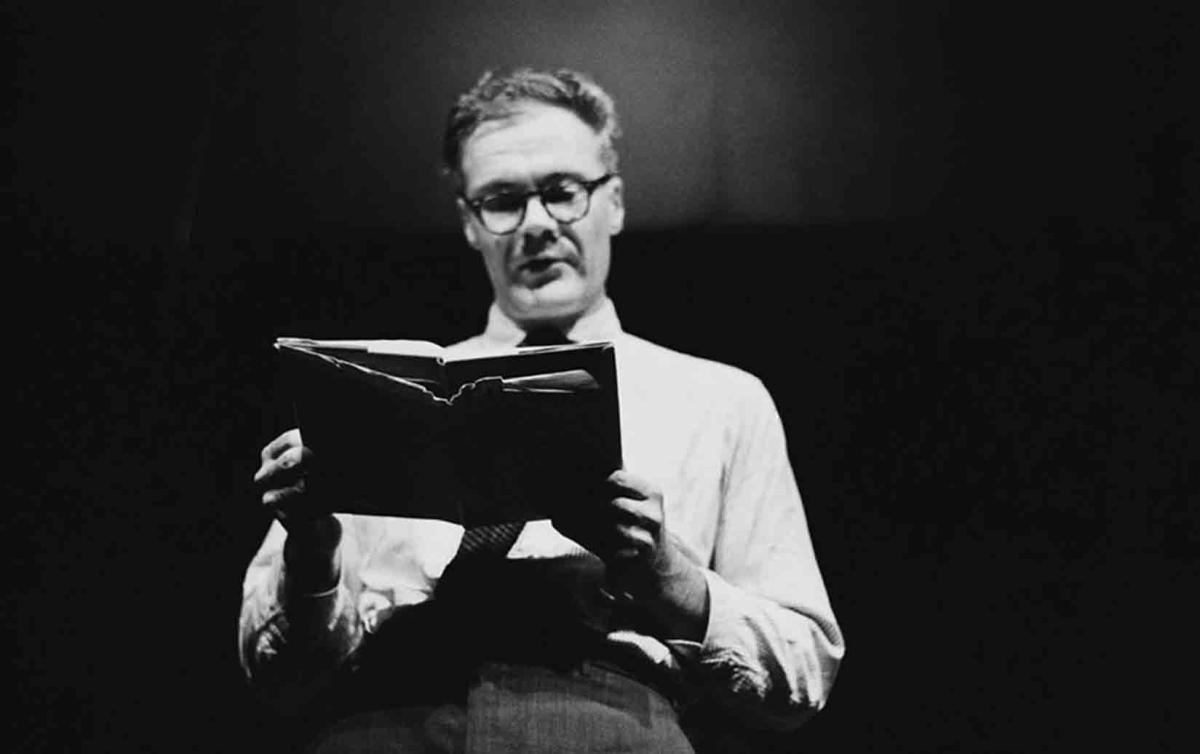

Lowell, meanwhile, was checking in and out of McLean and continued teaching and writing. The collection For the Union Dead appeared to wide acclaim in 1964, the title poem containing many of the lines he is best known for. The setting is Boston, familiar to Lowell since childhood but now changed: “The Aquarium is gone. Everywhere, / giant finned cars nose forward like fish; / a savage servility / slides by on grease.” Lowell once read the poem to an audience of thousands in Boston who demanded several encores. Part of what he had to offer as a teacher in creative writing seminars was the masterful way he read poetry out loud. Not all poets have the knack of recreating the emotion that they poured into the birthing of the poem in the first place. Formally trained readers in the field of oral interpretation study this—felt sensing—and apply themselves sedulously to develop it. Lowell may have had it within himself naturally.

National Humanities medalist and novelist James Patterson recalled in an interview in Humanities magazine his times as a psych aide in McLean Hospital, where he heard Lowell reading aloud. Lowell had again checked himself in. What Patterson remembers vividly to this day is the poet, lying in bed, picking up one of his books and reading his poems to a small group of staff, every one of whom was riveted.

After his time at B.U., Lowell taught, in 1963, at Harvard University, where the critic and scholar Helen Vendler attended his classes. As a teacher, she observed about Lowell, the best thing he did for his students, while introducing them to the poems of a new poet under study, was that “he gave them the sense, so absent from textbook headnotes, of a life, a spirit, a mind, and a set of occasions from which writing issues—a real life, a real mind, fixed in historical circumstance and quotidian abrasions.” A few years later, Norman Mailer met the pacifist Lowell during protests over the Vietnam War and remarked, in The Armies of the Night, that Lowell struck him as a “strangely wounded spirit, a man of high aristocratic guilts and cosmic sorrows.”

Lowell, searching for a drug that would balance his mind, shifted from Thorazine to lithium carbonate over the years but to no avail. He had always been a heavy drinker—while living in London he walked out of an institution, where he had been confined, to visit local pubs—but he suffered as well from heart illness. He died in September 1977, age sixty, of a heart attack while in the back seat of a cab that had just brought him from Kennedy Airport to his home on West 67th Street. He outlived his two most famous protégées—Sexton having committed suicide in 1974. Wounded spirit or not, Lowell’s contributions to American letters were vast, both as poet and, as Sexton and Plath might attest, as a teacher of poets.