As I sit looking out on the fourth major storm of the year, the white flakes falling like pin lights, I can’t help but think of Hayden Carruth’s North Winter.

Written in his former cowshed over a period of many months in the harsh northern Vermont winter, it’s a meditation on living with wood heat, iced windows, and relative isolation. Here is section seven of the booklength epic poem:

Twenty-two degrees below zero

and only the blade of meadow

like a snowpetal or foil of platinum

to defend the house against the glistening

mountain and the near unwinking

moon.

Before long, you realize Carruth was alone with the North Country winter like Thoreau. Even though he was not fond of Thoreau, there were likenesses: stubborn, self-reliant naturalists in shelters of their own making. But Carruth used different tools to explore what his self-imposed exile meant—a long, narrative poem that wove in and out of his daily observation from his nine-foot-square writing shed. Ironically, he depended on the people in his rural Johnson community, because of his meager income writing reviews and essays for the literary quarterlies. Some of his best poems are from the two decades he spent writing in that shed: “Marshall Washer,” the farmer he became closest to, “Regarding Chainsaws,” his tribute to trying to revive a tired chainsaw, and “Emergency Haying,” his ode to both conscripted labor and to the dying farms of farmers all around him. Those farmers, too, lived with the moon-quiet black elms he describes in section seventeen.

Like a frozen lake the sky in the bitterest

twilight cracks and rays of a black elm

rising a spray of limbs reveal

the longdrowned lurid moon.

There is another reason he sought out northern Vermont: He had just come from a period of struggle with alcohol and mental health. Despite having been the former editor of Poetry at twenty-eight—and close friends with poets Denise Levertov, Adrienne Rich, and Carolyn Kizer—he could not find purchase in the tough New York literary community. What he wanted was to rectify that perception and so began a period of intense creation—multiple long poems, books, essays, and a novel. He was never satisfied: “I’m a perfectionist; I don’t know what else to be.” Years later Sam Hamill, the founding editor of Copper Canyon Press, called to ask to republish Sleeping Beauty, his booklength poem on love. Written in “paragraphs,” a sonnet-like form he invented with a rhyming couplet in the middle, Sleeping Beauty is now considered a classic in American poetry. As are his Collected Shorter Poems and Collected Longer Poems—the legacies of a poet who wrote in multiple forms: sonnets, georgics, free verse, haiku, and jazz poems. In 1996, he won the National Book Award for Scrambled Eggs & Whiskey. Hamill would be his publisher until Carruth’s death in 2008.

Like so many poets, Carruth wrote in literary anonymity when he started on “North Winter.” There was no easy way to proceed; he chose the north woods and believed in being with whatever came to him. Paradoxically, much of what he found was measured in the silent affirmation of his surroundings, a window to the lesser-known satisfaction of following the tracks of pad and paw. Somewhere in the middle of this isolation he broke free and became a participant in a wild he had not imagined. The persistent cold wore into him so that he was able to capture what was vital and would not be extinguished by winter. He became a mapmaker of his environment; he studied and recorded the presence of stone, wood, and water.

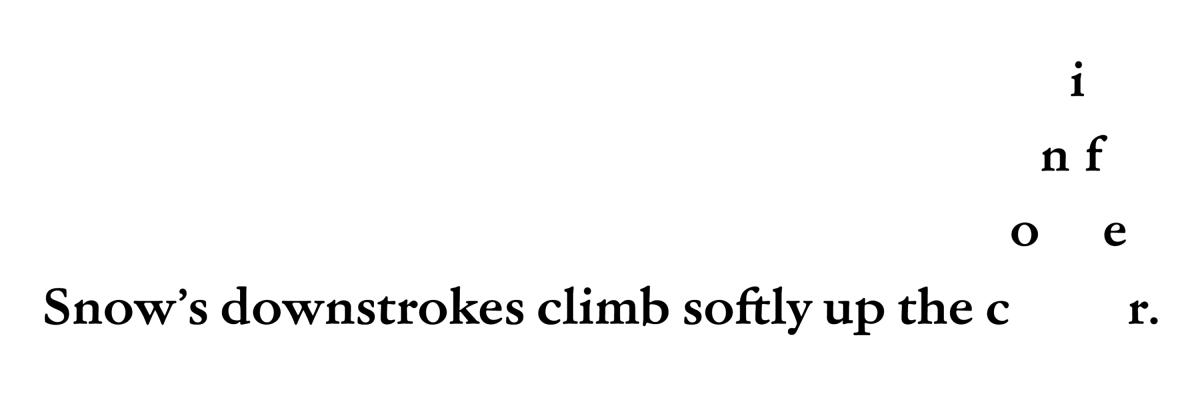

I doubt this contemplation was easily obtained; he did not know what he would write in months of effort. Resolution came in the act of living in that place: making a fire, reading, and questioning, sorting from the dark, shortened winter days to find “a crackling thorn aflame in the meadow’s / cold cold.” Or it could be an almost childlike perception of snow as in section forty-two, in which “conifer” is spelled out in the form of a tree on the page—with the i at the tip:

He was trying to find the name of winter without him: winter that only the plants and animals and stars abide. Winter without a label of man. Winter next to Foote Brook Creek with water unseen for months. In his quest to unearth the lexicon of what was before him, he stripped himself of patterns and habits to be a full partner in the cadence of the day. First light, low in the southeastern sky, the crack of ice on the step, the boot print in the late flurry. And then, he warmed the building and returned to the desk with some memory of being at the unfolding of awareness. Although Carruth was anything but spiritual, North Winter is like reading a spiritual journey—and because he is mostly not in the poem—it is the experience of what was all around him that is shared. Like Bashō, Carruth turned to the elements, and this choice enabled him to begin without supposition. This is where much art begins: on the threshold of exposure—the not knowing that is required before one can go on. Carruth would never say as much, but he was looking for, if not an answer, a passage into the north Johnson winter beyond his cowshed. He did not know what would happen; he understood it was an opening to fresh experience.

That is why I return to this poem—it is a meditation on being present, the distillation of time set against the all too unnatural world. This was Carruth taking measure of the essential particles of his existence. His presence was finally effaced from the poem. Out of the darkness of that winter came not just a remarkable poem, but the rebirth of one of the great poets born in the 1920s.

“Afterword: What the Poet Had Written:”

north is the vacancy that flowers in a

glance wakening compassion and mercy and

lovingkindness the beautiful dew

of the sea rosemarine the call crying in silence

so distant so small and meeting

itself in its own silence forever north is

north is the aurora north is

deliverance emancipation . . .

. . . north is

nothing . . .

Passages from North Winter reprinted with permission from Copper Canyon Press, Collected Longer Poems, © 1992.