The women in Mary Cassatt’s pictures don’t have time for you. They are perennially busy, lost in a good book, spying on others at the opera. Their blush-pink gowns and laurel leaf-printed dresses belie a world in motion.

Cassatt pictured women as they are, in the throes of life, in its interludes. Her touch was delicate, precise, and occasionally threatening. Even Edgar Degas, one of Cassatt’s close friends, grumbled, “I will not admit that a woman can draw that well.”

Her brilliant oeuvre, on view in a traveling survey that ran at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and opened this fall at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, unfolds like a story book. Lining the navy, mint-green, and lilac walls were women sitting down to tea, perched in theater boxes: all enigmatic, none with time to spare.

The only American to show with the Impressionists, Cassatt was fiery, sharp-witted, and, the Pittsburgh Daily Post noted in 1899, “as powerful as Balzac in setting a fact down.” In her lush oils and prints, velvety pastels and sketches, she fixed her gaze on the transient, the fleeting, imbuing it with grandeur.

“Cassatt has the tools of the old masters,” says Jennifer Thompson, who co-curated the show with Laurel Garber, “but is determined to forge new ground.”

Born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, in 1844, Mary Stevenson Cassatt traveled to Paris and Parma, Madrid and Cairo, art foremost in her mind. She was a beauty. “Once having seen her,” the collector Louisine Havemeyer remarked, “you could never forget her.” Famously private, Cassatt left behind no diaries or photos of her studio.

What one should strive for, she pronounced, in 1909, is “superior art” and “a hidden personality.” But in the spare print Reflection, we get a glimpse of her. Seated, spine straight, hands folded in her lap, Cassatt looks out wistfully, as if waiting to speak. Rendered with sharp, spindly linework, she is transfixing, her stare bright under the shadowed flounce of her hat.

Cassatt had blue-gray eyes, her biographer Achille Segard wrote, “the color of still water.” In her pictures, a glance says everything. As she stressed to her nephew, in 1881, he should draw his portraits “beginning with the eyes.”

Yet her sitters rarely meet our gaze. In Woman in a Loge, an operagoer peers out, bathed in the theater’s warm light, the gold-lined balconies echoing her rich, copper-tinged tresses. Clad in a bubblegum-pink gown, red and white blossoms falling off one shoulder, she watches those around her as she herself is watched. Everyone in Cassatt’s world is on view. In the Loge, mounted nearby, offers up another voyeur. Attired in black, a woman spies through binoculars something across the way, unseen. “What curious lives people live,” Cassatt once observed. She was a chronicler of women as she saw them: elegant, nervy, their minds perpetually at work.

Consider Cassatt’s frenzied letters. In one, she darts from the existence of a higher power (“I cannot understand a personal God”) to opining on a new museum; in another, she sprints from buying and selling artwork to musing on World War I (“Humanity is always the same”). Her sentences are winding, many unbroken by commas, as if her thoughts move too fast for her pen. She had a critic’s impulse, decrying Matisse’s “dreadful” pictures and Renoir’s women, whom she found “enormously fat” with “very small heads.” Cassatt’s snubs were pointed, swift, like a spider that taunts before disappearing into the wall. Often signed “heaps of love” or “affectionately yours,” her missives are dashed off in a hurry: With Cassatt, there’s always somewhere else to be.

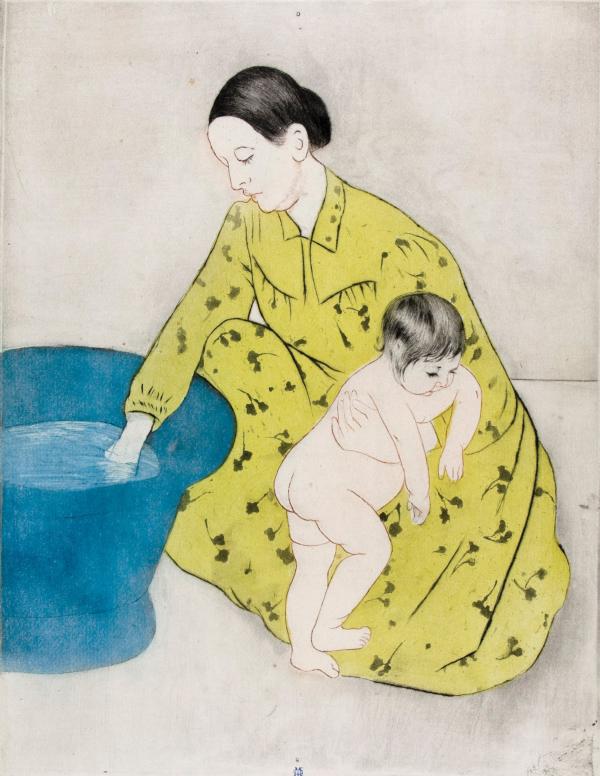

In her printmaking, she slows down. Spellbound by the Japanese woodcuts she saw in Paris, in 1890, Cassatt mused, “I dream of it and don’t think of anything else.” That year, she began etching on copper plates. The result: a set of ten impeccably colored pictures, “charged with meaning and tension,” says Garber. Arranged on a charcoal-gray wall in the galleries, each is a window into a woman’s life as it is happening. In one, a figure seals an envelope, her exquisite brocade dress patterned with cobalt blues. In another, a woman is at a fitting, the stripes of her dust-pink gown echoing her seamstress’s rumpled frock. Cassatt relished the details: the graceful cut of a skirt, the supple lines of a hand. Picturing a woman bathing a baby, Cassatt lingers on her lemon-yellow dress, dotted with black, tendril-like branches. That many of her figures were not mothers, but paid models, only adds to Cassatt’s artistry. She didn’t just see women, she staged them, each caress timed to perfection. When a pair of women sit down to tea, Cassatt leans one forward, intently, while the other, still in her coat, anticipates her getaway.

Cassatt was “attentive to the rhythms and activities of women’s lives,” Thompson asserts. That may be her abiding gift: a delight in those around her, in the beauty of the everyday.

For Cassatt, that beauty was quiet, subdued, easy enough to miss. In a sumptuous oil, one of the first in the show, a figure washes her face in a teal-rimmed basin. Set before a coral-pink wall, it is an objectively mundane scene. But in Cassatt’s hands, we are right there with the pictured woman, rushing, frantic. The figure is not a stranger. She’s a friend, a mother, someone with whom we can dispense with pleasantries. I can’t stop and chat, one can imagine her saying, but if you don’t mind me getting ready, I’ll listen.

Cassatt was always listening. In a picture of her sister, Lydia, crocheting in the garden, we can almost hear the birds chirping, the flowers rustling in the wind. She dappled the scene with periwinkle irises, sprays of wildflowers and luscious cerise roses. (Cassatt could tell rose varieties apart by scent alone.) She was an artist attuned to the world, imbuing her pictures with wonder. In a marvelously toned pastel, a woman plays the banjo in a leg-of-mutton-sleeved gown, a girl over her shoulders, looking on. There’s something intimate about the work, a profusion of lime green, peach, and indigo. The two aren’t aware of Cassatt. They’re lost in the melody, in the strumming of strings.

Cassatt’s women are easily carried away. In one expansive oil, we see Lydia steering a carriage through the park, Degas’s niece by her side. A lifelong traveler, Cassatt was once thrown from her carriage. “I have had the blackest eye I suppose any one was ever disfigured with,” she bemoaned, in 1890, and “patches of red & blue on my forehead.” Two years earlier, she fell off her horse when it was stung by a viper. But Cassatt was not one to lick her wounds. She returned to her pictures as one might a lover, voraciously and with abandon. She spent hours in her studio, clad in a crepe de chine smock, adding one stroke then another until she was satisfied.

“I work,” she confided in the architect Theodate Pope, in 1903, and “that is the whole secret of anything like content[ment] with life.” She saw her pictures, and those of the other Impressionists, as a new front in the war for artistic freedom. “We are carrying on a despairing fight & need all our forces,” she heralded, in 1878, adding, years later, that “to escape the tyranny of a jury is worth fighting for.”

Cassatt fought every day. When a worker told her it would take six weeks to build one of her elaborate borders, she resolved to craft it herself, a hammer and tongs in hand. By evening, she declared it would be done in six days, not weeks. Cassatt gave herself over to art, her one true and enduring passion. “I have had my joy,” she penned in a 1924 letter to the curator William M. Ivins. “I have once more stirred a feeling of art—and nothing you or any one else can offer me, could give me that pleasure.”

Cassatt never married. While she kept in close contact with family and friends, her longest relationship was with her pictures. “I have worked for forty years and I feel I need forty more,” she once admitted to Louisine Havemeyer.

In her fifties, Cassatt’s eyesight began to fail. By 1904, she stopped painting, and, a little more than two decades later, she died in her chateau outside Paris. All the while, Cassatt knew, instinctively, that her work would live on: “In art what we want is the certainty that the one spark of original genius shall not be extinguished, that is better than average excellence, that is what will survive.”

The show closes with a spark of that original genius. Flopped on a cerulean chair, a girl is lost in thought. The light, filtered through French doors, brings out the glossy blues of the furniture, inflected with daubs of pink, red, and a smattering of gray. It’s a scene of reverie, with all the brilliance of a jewel. In 1872, Cassatt saw an oil by Diego Velasquez and gushed, “Good heavens, why you can walk into the picture.” So, too, with this little girl, dreaming the day away.

At an Impressionist exhibition, Cassatt was chatting with someone who didn’t recognize her. The conversation turned to artists. “You are forgetting a foreign painter whom Degas rates very high,” the stranger pointed out, “Mary Cassatt.” Delighting in her anonymity, Cassatt quipped, “Oh, nonsense!” At that, the stranger turned away, muttering, “She is jealous.”