In the late 1930s, a man named Carl J. Kress would often visit a county park in northern New Jersey, the Eagle Rock Reservation. He’d ascend to its scenic overlook in the early-morning hours and perch there, gazing out at the vista below: the crowded suburbs, Newark in the foreground, Manhattan in the distance. He’d take a breath. Then, he would yodel. He did this until one morning a police officer followed him up and intervened. Kress was soon back again, however, carrying a permit from the Essex County Park Commission that allowed him to yodel lawfully every day for 45 minutes, from exactly 8:00 a.m. to 8:45 a.m.

Kress’s yodeling spot, by the way, was once an observation post where George Washington’s troops watched for Tory raiding parties, and from it you can see the former homes of the pacifist writer Randolph Bourne and the landscape painter George Inness, as well as a house where Washington spent a night and is identified by a boulder resting on a patch of grass that was once declared the smallest park in the world. Nearby, too, is the birthplace of President Grover Cleveland, a motorcycle stunt path, and what was, at the time, the world’s largest laundry facility.

All this I learned from New Jersey: A Guide to Its Present and Past, published in 1939 and researched, written, and edited by the Federal Writers’ Project. I am a native New Jerseyan and have stood many times on that very overlook, but I knew nothing of its history until I opened the guide. Thanks to the intrepid federal writers and their 735-page book, I also learned about my state’s flora and fauna, its geology and industry, its Native inhabitants, its labor movement and its contributions to the arts, and its folklore—including two full pages on the Leeds Devil, known as the Jersey Devil (“One report is that he is writing a thesis, A Plutonian Critique of Some Awful Aspects of the Terrestrial Life, in preparation for a doctoral degree from the University of Hell”). And, yes, there are driving directions: 269 pages of them.

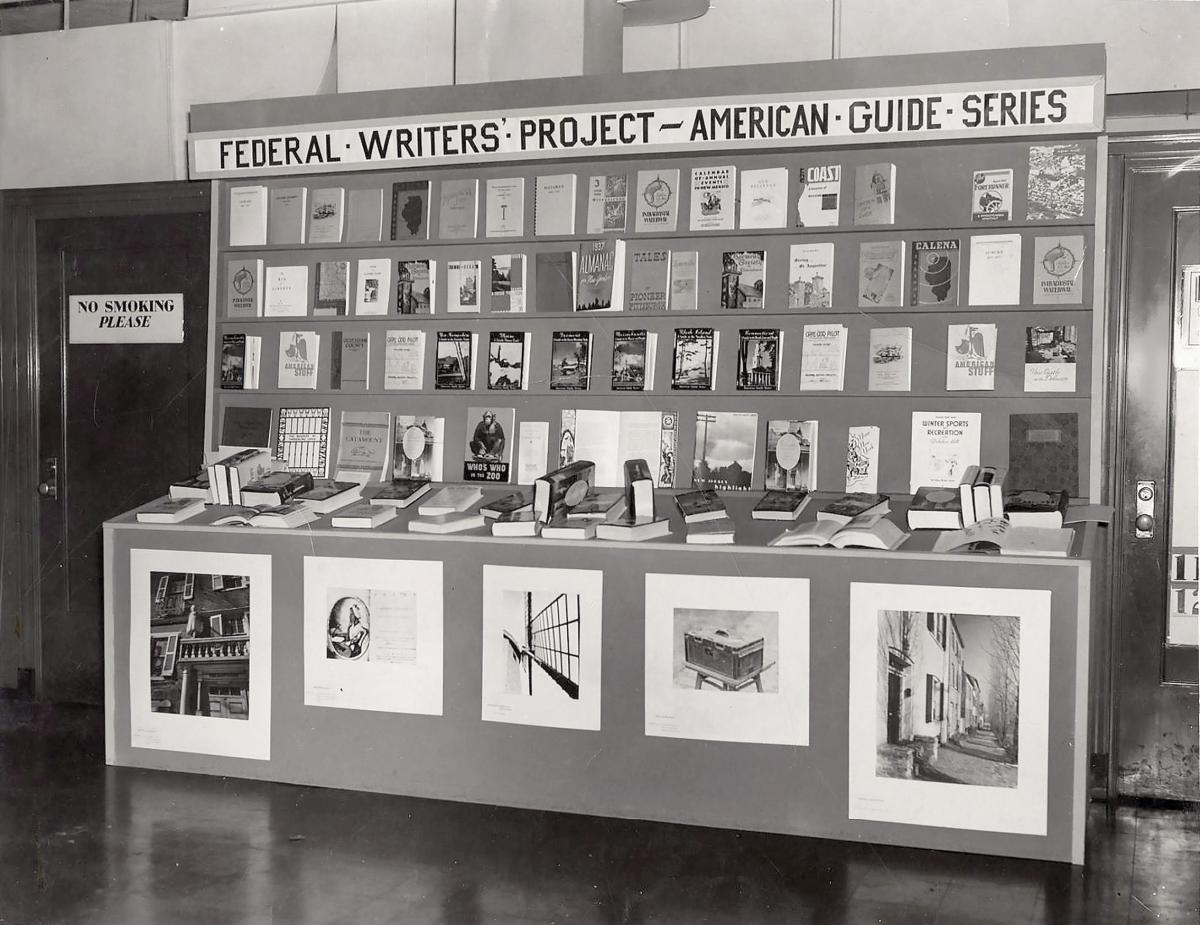

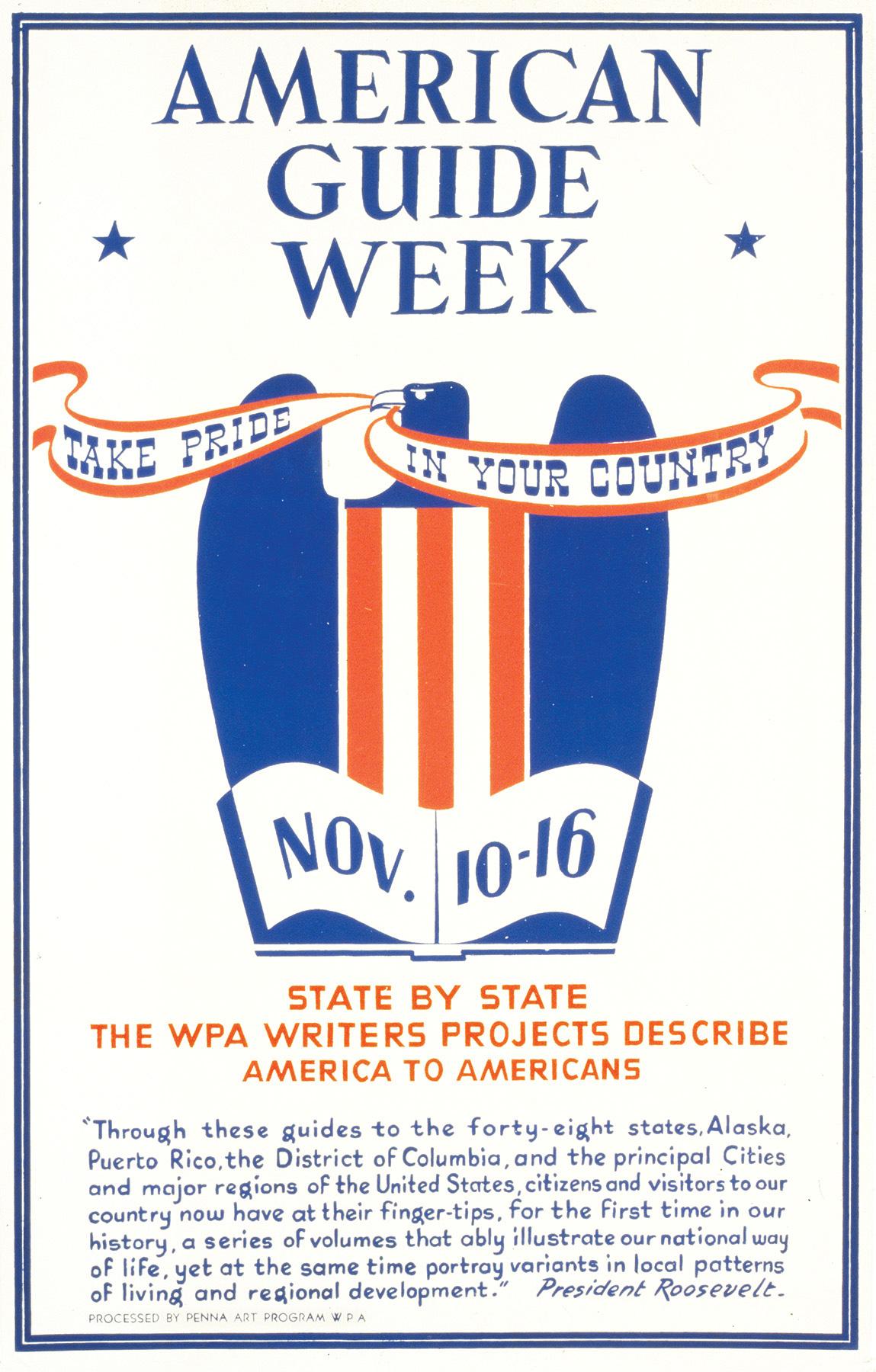

New Jersey is a typical entry in the FWP’s American Guides series, published during the late 1930s and early ’40s. The series comprises shaggy biographies of all the then 48 states; pick one at random and you’ll find a smorgasbord of history, legends, jokes, industrial data, social analysis, epitaphs, old letters, old newspaper clippings, old diaries, ghost stories, dubious tales, and half-forgotten anecdotes. You’ll find handsome line illustrations alongside photographs of houses and monuments and people at work. You’ll find scattered, subtle reports on how people were sustaining themselves through the Depression and how New Deal policies were reshaping the country. You’ll find a little practical advice for travelers and a lot of information whose purpose is more obscure. You’ll find a guidebook that seems, itself, to have wandered off and gotten lost.

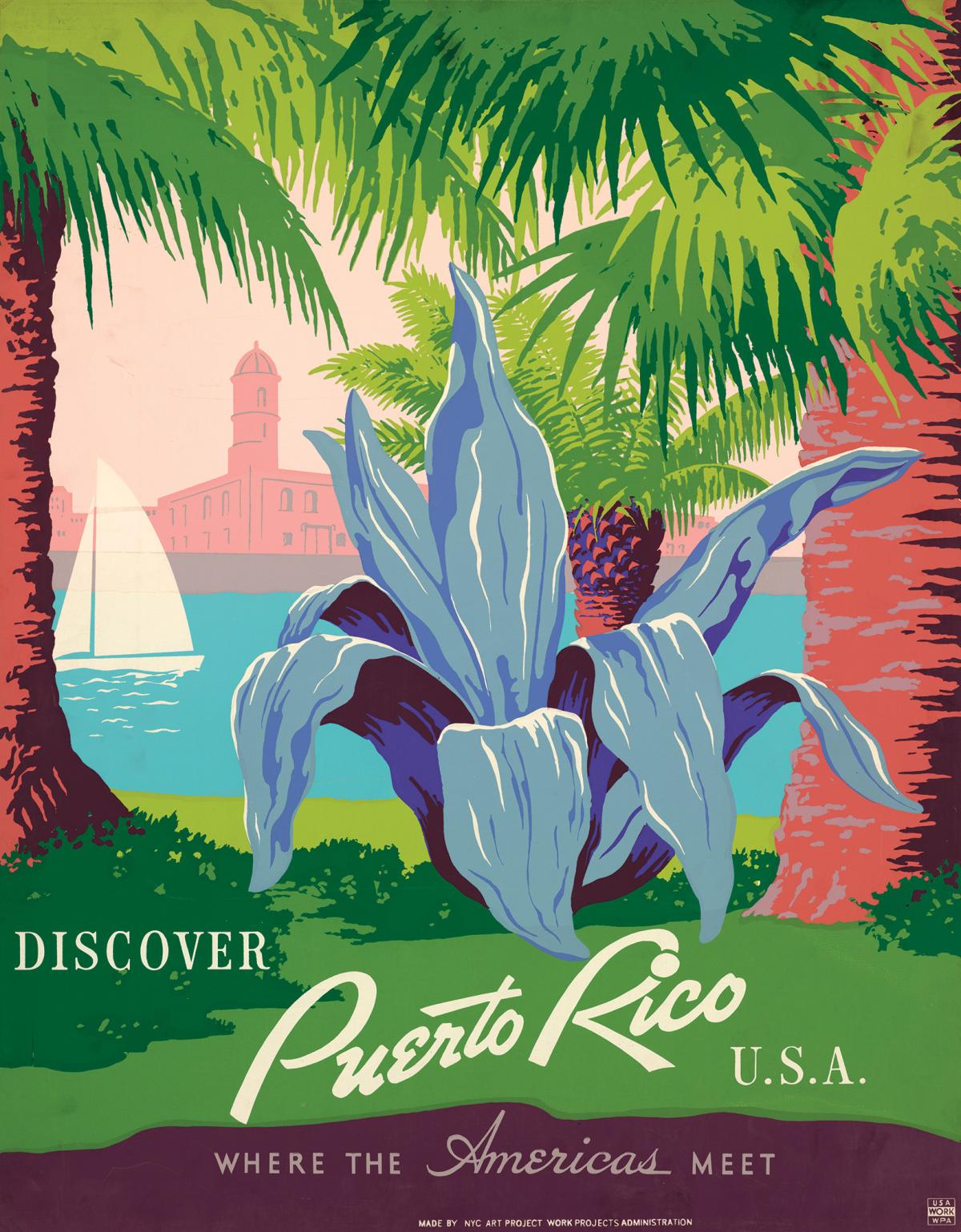

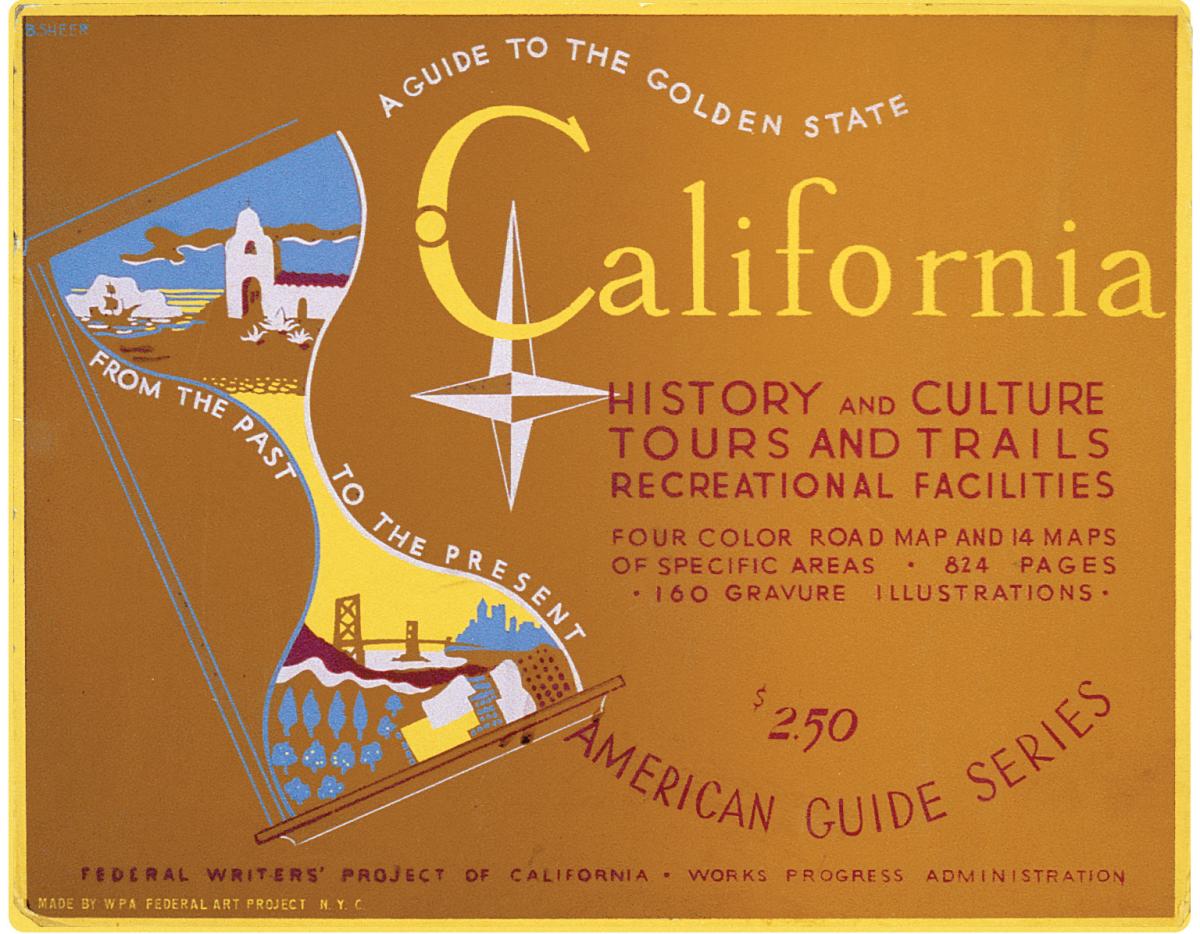

In their best moments, the American Guides are engrossing, artful, and surprising. Some you can read cover to cover, and all of them reward leisurely skimming. Along with the state guides, there are books about the Alaska territory and Puerto Rico; many cities and towns, including a pair of volumes on New York City and a massive guide to Washington, D.C.; destinations such as the Berkshires and Death Valley; transportation routes such as U.S. 1; studies of ethnic groups and industries and the natural world; as well as uncountable pamphlets, bulletins, and ephemeral publications. I do mean “uncountable”: No one knows how many books and pamphlets the FWP created during its lifespan, from 1935 to 1943. When I was researching the project, roughly a thousand struck me as a good guess. Since then, I’ve spoken with a collector who owns more than 1,500 publications and believes there may be hundreds or thousands more. And this isn’t counting the staggering amount of material sitting in the National Archives, in the Library of Congress, and in collections around the states.

Did anyone in 1935 foresee the FWP becoming so vast and so prolific? I doubt it. The project had a simple purpose: It was designed to create jobs for out-of-work novelists, poets, journalists, editors, teachers, clerks, and other white-collar workers. What these federal writers would write didn’t much matter. The point was to get unemployed people off the relief rolls and into useful jobs. This was the mission of the FWP’s parent agency, the Works Progress Administration, and while the WPA put millions to work rebuilding and expanding the nation’s infrastructure, its subset of federal writers began assembling a series of guidebooks—initiating, almost by accident, a bold literary experiment unlike anything attempted in American history.

The FWP’s architects might have chosen another task: compiling a manual of government functions, for instance, or issuing press releases. But guidebooks were an appealing, practical, innocuous option. They were labor intensive, which fit the purpose of a work-relief program. They had the potential to generate political goodwill in the states they covered. And they could pump some life into the economy by stimulating travel and boosting the commercial publishing houses, printers, and booksellers that would ultimately bring them into the world. (With few exceptions, the guides were published by trade and academic publishers such as Random House and Oxford University Press.)

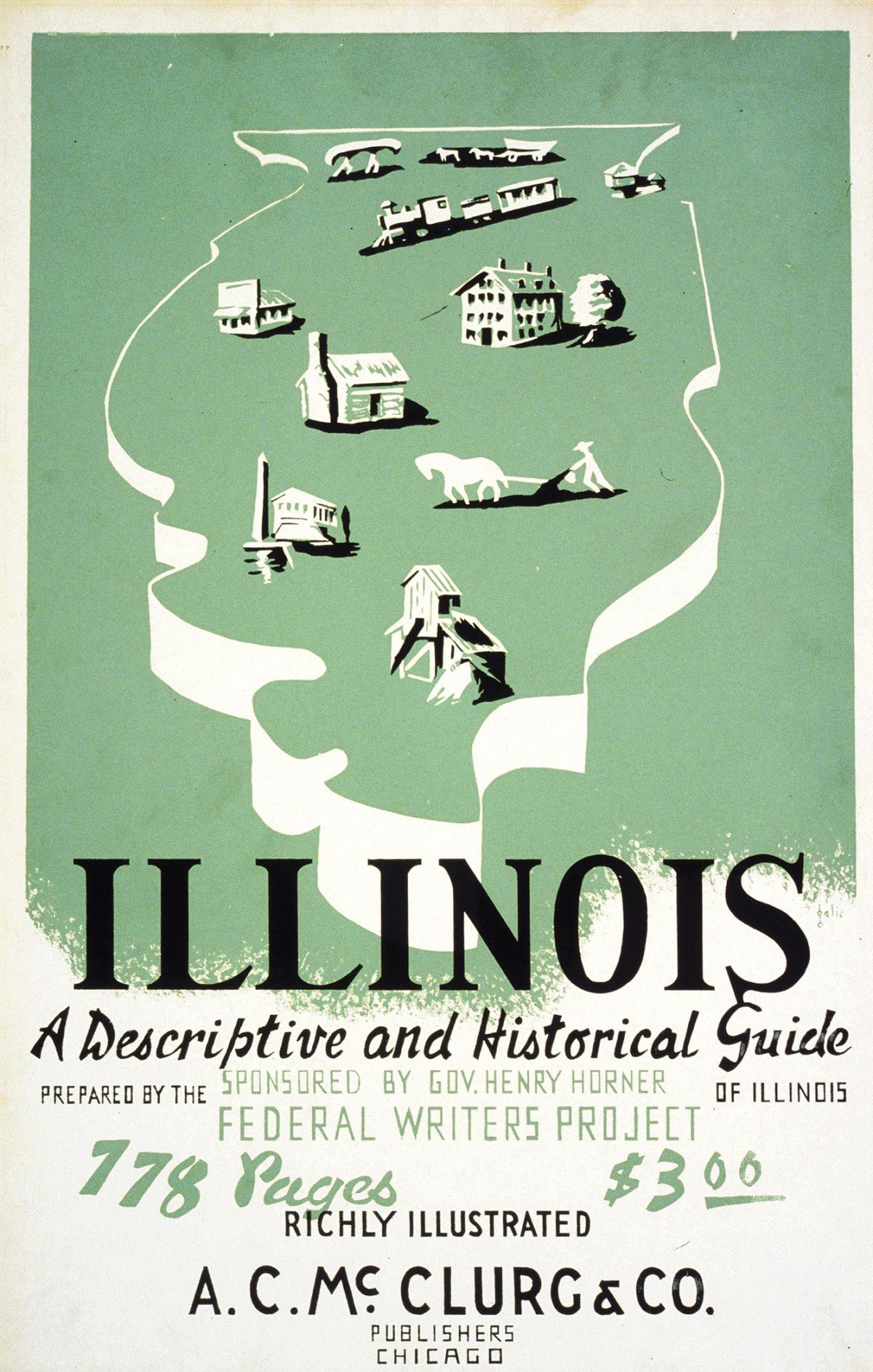

When the books did appear, though, they hardly resembled the slim, functional Baedeker or Blue Guide they were meant to replace. They were sprawling things, divided into three hefty sections. First came substantial essays on various subjects—history, local government, the arts, and so on. Some of those essays were unique to their state: California had “The Movies,” Tennessee had “Tennessee Valley Authority,” and Illinois had “Man of Illinois,” an encomium to Lincoln, written by the governor—an enthusiastic collector of Lincolniana—Henry Horner. After the essays came detailed profiles of cities and towns, and then dense, meandering tours.

The guides, in other words, didn’t simply direct you from one spot to another. They embraced the American land with a capacious fervor that might have made Walt Whitman blush. The person most responsible for this maximal approach was the FWP’s first director, Henry Alsberg. He was an unlikely captain of the project: an affable but notoriously disorganized administrator, trailing a hodgepodge of a career in journalism, law, relief work, political activism, and theater. And yet, Alsberg was the crucial visionary the project needed. From his headquarters in D.C., he and his editors designed their ambitious plan for the American Guides and put the basic structure of the FWP in place, setting up offices in every state, hiring state directors, and ordering thousands of federal writers to fan out into cities, towns, and rural hamlets.

As federal writers surveyed the American scene, they interviewed prominent citizens and local oddballs, elderly chatterboxes and exhausted workers. They combed through church records, municipal archives, and newspaper morgues. They dug around in people’s attics and canvassed cemeteries. They drove miles upon miles of roadways. Some spent weeks or months wandering library stacks; others worked entirely in the field. From this frenzy of activity came notes, reports, and transcripts, which they then transformed into the raw copy that flowed into the state offices. There, editors assembled the rough guidebook manuscripts, and then national editors in D.C. added another layer of scrutiny. The ensuing back-and-forth—checking, revising, and much rewriting—was often contentious.

Through this process the FWP generated far more material than the guidebooks could possibly absorb. Soon, federal writers began collecting life histories, testimonials, folklore, and other material as ends in themselves, with an eye toward future publication. This included the narratives of elderly Black citizens who’d been born in slavery, which would become one of the project’s best remembered undertakings.

But the guides were the main drivers of activity, and as the national editors packed them full of information, the tours—road trips that traced the length and breadth of each state, pointing motorists toward historical attractions, scenic vistas, and local curiosities—morphed into Dada-esque literary collages. Alsberg, who once compared writing a tour to composing a sonnet, understood how the mastery of a rigid form could stimulate a writer’s creative powers. Among the FWP’s leaders, though, it was a national editor named Katharine Kellock who oversaw the tours and shaped them into the project’s signature aesthetic achievement. Her efforts were a success. The historian Bernard DeVoto, reviewing a batch of newly published New England guides, called the tours “an unquestionable triumph,” and noted how they jumbled up the present and the past, the grand and the mundane. “It is a rich, various and rewarding spectacle that the tours compose,” DeVoto wrote, “a heartening reminder of how complex the current scene is and on what a variegated and fascinating base it rests.”

Today, these tours are partially obsolete. Some of the sites they describe are gone, as are some of the roads. But they’re still usable, and they all work wonderfully as arm-chair excursions. Take, for instance, Tour 1 from Oklahoma: A Guide to the Sooner State, which travels along Route 66—as it “runs the gamut of hot and cold, mountains and prairies, beauty and sordid ugliness”—passing mountains of “chat” waste rock from lead and zinc mines; the site of a trading post called “Jimtown” after four local farmers, all named Jim; the just-completed hydroelectric Grand River Dam, constructed by the New Deal’s Public Works Administration; the location of the annual Will Rogers Memorial Rodeo; the Eastern Oklahoma Hospital, where a pseudonymous mental patient, “Hospital Inmate Ward 8,” wrote the book Behind the Door of Delusion; a warplane assembly plant; the dance grounds of the Creek and Euchee (Yuchi) Indians; the town of Chandler, virtually destroyed in 1897 by a tornado, except for a single Presbyterian church where the townspeople had sheltered; the Home of the Poor Prophet, a never-used state capitol taken over by an eccentric insurance broker who “attempted to carry out sociological experiments”; the former Camp Alice, where in 1883 renegade Kansan “Boomers” illegally settled and were repelled by the U.S. infantry; Reno City, whose buildings were entirely transported across the shallow riverbed, except for a three-story hotel, which got stuck midriver yet continued to operate; an eight-foot-tall petrified tree stump near the Rock Island Railway; a life-sized replica of the Crucifixion scene within a Catholic cemetery; and an old salt spring that was a favorite resting spot for “beeves” during cattle drives—just to name a few items, from one of Oklahoma’s sixteen tours.

The American Guides, in the aggregate, contain thousands of such tour pages. With the thousands more allotted to essays and city profiles, the books form a national self-portrait, constructed from the ground up, that is difficult to fully comprehend. But it would be wrong to dismiss the guides as extravagant boondoggles. They were emblematic of a distinct cultural trend of the 1930s, when artists and writers fused social documentary methods with American themes and images, as they sought to portray the hard realities of the Depression while pondering the richness of the country’s past. This trend, building for years, accelerated as old preoccupations with Europe and antiquity gave way to a new emphasis on American culture in its many expressions, from literature to architecture to folkways.

The New Deal contributed to this moment, not only through the WPA’s writing, art, music, and theater projects, but also its Index of American Design, Treasury-funded post office murals, Farm Security Administration photographs by the likes of Dorothea Lange and Gordon Parks, and films such as Pare Lorentz’s The River—even Woody Guthrie songs commissioned by the Bonneville Power Administration. All these undertakings shared an impulse with the literary criticism of Alfred Kazin, Van Wyck Brooks, Constance Rourke, and F. O. Matthiessen, and books that combined text and photographs, such as Margaret Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell’s You Have Seen Their Faces and James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The guides exemplified this “literature of nationhood,” as Kazin called it, whose aim, in an era of economic crisis and looming war, was “to chart America and to possess it.”

It’s less clear how the FWP shaped literary work to come. Today, discussions of the project tend to focus on its famous alumni, and there’s no doubt the FWP supported the careers of established writers such as Conrad Aiken, Zora Neale Hurston, Anzia Yezierska, Jack Conroy, and Vardis Fisher, while launching the careers of younger writers such as Richard Wright (who wrote Native Son on the FWP payroll), John Cheever, Saul Bellow, Margaret Walker, Ralph Ellison, Meridel Le Sueur, and Studs Terkel. Some of their later work contains traces of FWP material and even more of the project’s sensibility. The scholar Sara Rutkowski has argued that the FWP, through the attention it paid to first-person testimonials, helped initiate a turn toward the more inward-looking, psychologically oriented fiction of the postwar era, what the critic and editor Malcolm Cowley, writing in the 1950s, called “personalism.” It was not for nothing, Rutkowski points out, that Cowley’s three examples—Ellison, Bellow, and Algren—had all been federal writers.

I suspect that the project’s influence, down through the literary generations, is deep but difficult to measure. I’m more interested in what the American Guides have to say to anyone who picks them up. There’s a lesson in these overstuffed, rambling books—about the American character and, indeed, about the nature of democratic citizenship. Think of the tours, which proceed geographically but are chronologically, thematically, and tonally chaotic: They are excursions into an America that exists not in fuzzy platitudes or in grand pronouncements but in all that rich, multitudinous, concrete detail, all the stuff of American life that neither privileges nor excludes the famous and the powerful but insists also on the ordinary, the obscure, the strange, the failed. The guides add up to a messily democratic portrait of America that demands an active participation on the part of the reader. You, holding the guide, must grapple with that heap of information and make sense of it. These are books, after all, that include both foldout maps and bibliographies: They invite us to explore America physically and intellectually, by hitting the road or raiding the library shelves or taking a closer look at your own local territory.

The FWP was shut down in 1943, along with the rest of the WPA. The project still attracts scholarly interest, in the form of books and articles and conferences, and it has even inspired legislation, now under consideration, to create a twenty-first-century FWP. This interest endures, I believe, because the project’s task was left undone. The federal writers developed a process for charting America that was so restless, so wantonly expansive, that it could only ever be continued or suspended—but never finished.

This was why Alsberg seemed so pleased by a certain tour in the New Jersey guide, one that passed through a swampy region with hardly any notable sites. To him, the tour was a meditation on the charms of swamps and on the appeal of a good ramble: no more, no less. The FWP took this sensibility and applied it to the entire nation. The guides don’t overlook the Great Men and seats of power—they are lousy with homes where Washington slept—but they also pause to look at swamps, ponder local legends, and devote a few lines to solitary, forgotten characters who rise at dawn to yodel.